The real estate industry is built on other people’s money. A lot of those investors will now be asking tough questions about climate change, thanks to new regulations proposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Late last month, the SEC announced that publicly traded organizations would soon need to disclose their climate change risks and exposure. The former includes direct physical risks to their business, such as the impact of sustained higher temperatures, sea-level rise or persistent wildfires, as well as transition risks stemming from the shift to a lower-carbon economy.

“We are concerned that the existing disclosures of climate-related risks do not adequately protect investors,” the SEC said. “For this reason, we believe that additional disclosure requirements may be necessary or appropriate to elicit climate-related disclosures and to improve the consistency, comparability, and reliability of climate-related disclosures.”

Because most large real estate players are private companies, they are not subject to these disclosures. And most of the big shops that are public, such as REITs, already disclose their emissions.

But the new regulations are likely to pressure the industry through the capital markets — publicly traded firms, including investment managers and big banks, which are key sources of debt and equity for major private real estate companies.

Your business is on the line if you forgo reporting in favor of fines.

The new disclosures mean they will ask tougher questions about how the property portfolios they’re backing are being built and operated. Publicly traded firms that lease space will too be pushed to make greater climate-conscious demands of their landlords.

Real estate operators have traditionally been lax when it comes to reckoning with climate change. Many have stuck their head in the sand or paid fines rather than deal with the problem. The SEC’s proposal takes that option off the table.

“The lifeblood of your business is on the line if you decide to forgo reporting in favor of fines,” stated seed-stage proptech investor Shadow Ventures on the new proposals, in a report the firm shared in advance of publication exclusively with The Real Deal. “You don’t disclose, you don’t get their business.”

Breaking down the mandates

TRD cut through the SEC proposal’s legalese and regulatory jargon to identify what real estate needs to know:

First, the proposal highlights climate-related events, — risks to projects and properties from wildfires, hurricanes, earthquakes, coastal erosion and the like. For example: How does sea-level rise affect the value of a South Florida or Lower Manhattan portfolio over the next 10 years? In the U.S. alone, roughly $1.3 trillion worth of real estate was at high or extremely high risk from wildfires alone, according to an Urban Land Institute report in 2020. Exposure has only grown since.

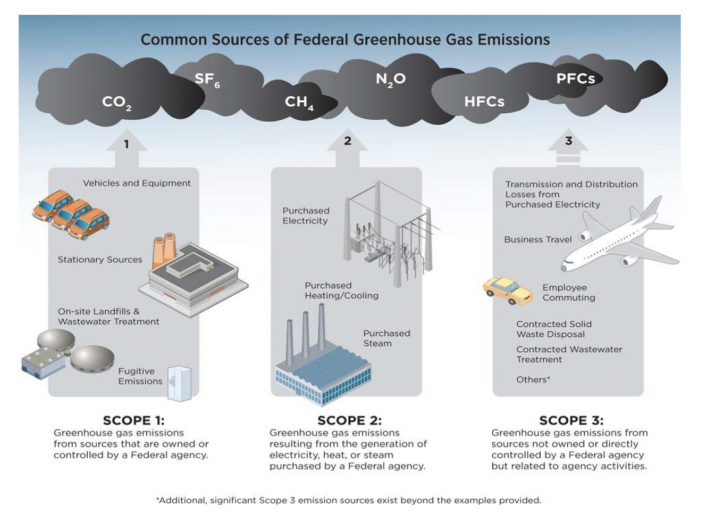

Second, the SEC will require companies to disclose their carbon footprint and greenhouse gas emissions, both direct and indirect. When it comes to buildings, it’s important to understand the different tiers of these emissions, widely known as “scopes.”

Scope 1: A company’s direct greenhouse gas emissions originating from a company’s owned assets

Scope 2: Indirect emissions from the generation of purchased electricity, steam, heating and cooling

Scope 3: Emissions from upstream and downstream activities in a company’s value chain

For a real estate owner doing business with a public company, Shadow Ventures speculates this would likely mean:

Scope 1: Emissions from building energy expenditure and other assets owned or controlled (vehicles, appliances, storage tanks, pipelines, wells, or other equipment directly by the company)

Scope 2: Purchased electricity or energy from assets owned or controlled by the company

Scope 3: Energy and water waste, materials purchases and inventory, construction waste, and emissions from all downstream suppliers and subcontractors.

Scope of greenhouse gas emissions (Source: Shadow Ventures)

It’s this last tier — Scope 3 — where things get interesting, industry insiders said. Landlords and developers would have to assess not only their own activities, but those of their whole ecosystem.

“I hope that this causes more pressure on our supply chain,” said Sara Neff, director of sustainability at Lendlease, a global developer and contractor. “I think this will create the market conditions to see more rapid innovation.”

Climate tech startups’ moment

The SEC is finalizing aspects of the ruling and requesting comments by May. Some companies would be required to comply starting in fiscal 2023. Investors in the space predict brisk business for climate tech startups focused on the built environment.

Jennifer Place, a principal on the climate tech team at real-estate focused venture capital firm Fifth Wall, described the SEC’s proposal as a “wake-up call for the industry and a step in the right direction.” She identified four buckets ripe for startups: analytics, compliance, mitigation and carbon accounting. Companies have traditionally siloed carbon-impact reporting from the rest of their accounting. Now, Place said, it would be more integrated.

Read more

Place is watching to see if the big accounting firms such as PWC and EY develop their own climate-reporting frameworks or absorb or invest in startups specializing in that. Making climate-reporting frameworks mandatory also helps tackle another problem: Self-policing historically doesn’t lead to great outcomes.

I hope this causes more pressure on our supply chain.

“This ruling is really going to help companies become aware of what their carbon emissions are,” Lendlease’s Neff said. “You’re motivated to start reducing them and reducing environmental impact.”

Other fields ripe for innovation, according to Shadow Ventures, are building management systems, materials engineering, and technology that makes construction faster and more efficient.

Built-world startups with a climate-focused message have seen growing interest from both generalist and climate-focused VCs over the past year. Clarity AI, a platform for sustainability data, raised $50 million in a SoftBank-led round in December. Icon, a 3D home-printing startup, hit a valuation of just shy of $2 billion after a Tiger Global-led $185 million round in February; and Turntide Technologies, which builds energy-efficient electric motors, raised $80 million last March in a round led by Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures.

The SEC’s new regulations would accelerate and increase such bets on the space, the investors said.

Innovation and implementation will be the only way forward, Ness said. Actions such as purchasing carbon offsets and renewable energy certificates, which allow real estate operators to avoid tackling the embodied carbon in their portfolios, are becoming unfeasible because their prices are skyrocketing, and figure to rise further as the SEC proposal increases demand.

“It is getting increasingly expensive,” Neff said, “to buy your way out of this problem.”

Write to Hiten at hs@therealdeal.com or @hitsamty on Twitter