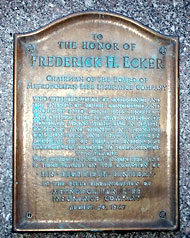

TRD Special Report:In August 1947, as the first tenants were moving into Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village, workers installed a small metal plaque on the west side of its central oval footpath. It was dedicated to Frederick Ecker, president of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and developer of the giant housing complex.

Ecker, the plaque read, had “brought into being this project, and others like it, that families of moderate means might live in health, comfort and dignity in parklike communities, and that a pattern might be set of private enterprise productively devoted to public service.” The inscription became a mantra for the 11,200-apartment complex, which, even as Manhattan became increasingly unaffordable, remained a rent-stabilized oasis for the middle class.

But in 2002, the plaque was quietly removed. Four years later, MetLife sold Stuy Town to developer Tishman Speyer and fund manager BlackRock, who planned to aggressively convert units to market-rate. Families of moderate means were suddenly of low priority.

The plaque is still missing today, more than five years after Tishman Speyer [TRDataCustom] surrendered the property. But last week, its message got a new lease on life: As part of a new $5.3 billion deal to buy the 80-acre complex, fund managers Blackstone Group and Ivanhoe Cambridge agreed to keep 5,000 of its apartments affordable for at least 20 years.

[vision_pullquote style=”3″ align=”right”] “… [Frederick Ecker] had brought into being this project, and others like it, that families of moderate means might live in health, comfort and dignity in parklike communities, and that a pattern might be set of private enterprise productively devoted to public service.” — Plaque at Stuy Town [/vision_pullquote]

The agreement, touted by Mayor Bill de Blasio as a “great victory” for middle class New Yorkers, is the biggest single deal to preserve affordable housing in the city’s history. It has made Blackstone, a private equity giant, a darling of tenant advocates and left-wing politicians and is, according to U.S. Sen. Chuck Schumer, “proof that a company can do well by doing good.”

How on earth did we get here?

I. The seller

After Tishman Speyer defaulted on its Stuy Town loans in 2010, CWCapital, a special servicer that is a subsidiary of Fortress Investment Group, took control of the complex on behalf of more than a dozen lenders. By last year, Stuy Town’s value had bounced back and CWCapital, seeing an exuberant New York investment sales market, decided it was time to sell.

But the sale hit an immediate roadblock: Several lenders sued CW for “misconduct,” accusing it of trying to keep control of the property and “reaping an unjust windfall” of $1 billion through a proposed sale. As the case dragged on, potential buyers warily circled the property. Without a resolution, Stuy Town could not be sold.

The breakthrough came early last month, sources said, when CW and the plaintiffs finally settled their litigation. For the first time in five years, nothing stood in the way of a sale. Doug Harmon got to work.

When MetLife put Stuy Town on the market in 2006, Harmon, of Eastdil Secured, had lost out on the plum assignment to his archrivals, CBRE’s Darcy Stacom and William Shanahan. Now, he had a second shot.

Stuy Town was no easy sell. Tishman Speyer’s failures, coupled with the massive political and legal backlash in the wake of its 2006 takeover, had spooked some suitors. One real estate investor, according to sources, told the sellers Stuy Town had become a “prostitute.”

“If I were to sleep with her, I might get HIV,” the investor reportedly said.

Instead of launching an open bidding process, Harmon pursued an off-market sale. He sent a video showing aerial drone footage of the complex to a handful of potential buyers. Attached to the email, sources said, was a “trap” to ensure no one was messing around: In order to review the property’s financials, potential buyers had to sign a confidentiality agreement and put down a $10 million deposit.

“Sometimes sellers don’t want an open bidding process,” said Clipper Equity’s David Bistricer, a real estate investor who is not involved with the deal. “There were a lot of sensitive issues, such as the litigation. I guess the owners and creditors didn’t want to go through all that publicity.”

Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village

Blackstone Group

Jonathan Gray

Ivanhoe Cambridge

CWCapital

Douglas Harmon

Alicia Glen

Even whispers of a deal could derail the whole process, Harmon believed. His caution paid off: News of a possible sale didn’t break until Oct. 16, three days before the contracts were signed.

It isn’t clear how many companies coughed up the $10 million, and Harmon and Andrew MacArthur, the key figure at CWCapital during the sale process, didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

But at least two serious contenders emerged, according to sources. One source with close knowledge of the process told The Real Deal there were three serious contenders – the partnership between Blackstone and Ivanhoe Cambridge and two private families.

Blackstone and Ivanhoe Cambridge soon emerged as the leading contenders. One source unaffiliated with the transaction complained that Blackstone was treated favorably and other bidders were never given a fair shot. But another source argued that the winners, flush with cash but still able to move quickly, simply had more to offer.

“There are not that many people who can write this kind of check and do it the right way,” the source said.

II. The buyers

Ivanhoe Cambridge’s CEO Daniel Fournier can’t quite recall who first called whom. “To be honest, we’ve been talking to Blackstone on and off on a lot of things,” he told TRD in an interview shortly after the contract was signed. The real estate investment arm of Canada’s second-biggest pension fund manager, Ivanhoe Cambridge and Blackstone have a relationship going back 20 years.

“We are the subsidiary of a pension fund that represents close to 8 million people and are looking for stable returns,” Ivanhoe Cambridge’s CIO Sylvain Fortier said. Blackstone had recently launched an open-ended core-plus fund, Blackstone Property Partners, and was looking to invest a lot of money in low-risk, low-yield real estate. Both saw great promise in Manhattan’s rental market, and both had been separately eyeing Stuy Town for a while. When they heard it was up for grabs, they quickly decided to work together.

Their proposal was almost the exact opposite of Tishman Speyer’s 2006 bid: They would take on little debt and keep the apartments as rentals, eyeing steady returns instead of swift profits. And they deemed it essential to win over the city, tenants and local politicians — perhaps in part to New York’s senior senator, Chuck Schumer.

At a tenant meeting at Stuy Town last week, Schumer said the Tishman Speyer saga had taught him the need for “outside leverage.”

“And I found a way,” he added. “I realized that to get such a huge mortgage, you need the backing of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.”

Schumer and Representative Carolyn Maloney began lobbying the Federal Housing Administration, which oversees Fannie and Freddie. In June 2014, the FHA declared it would only insure an acquisition loan for Stuy Town if the buyers had the blessing of the city and tenants, the New York Times reported at the time.

Blackstone wouldn’t comment on whether an FHA guarantee was an important consideration, though a source close to the firm said it is “hopeful to receive agency support.” On Wednesday, the Commercial Observer reported that Wells Fargo is leading the $2.5 billion acquisition financing, which will likely be provided through Fannie or Freddie.

A source close to the firm told TRD that Blackstone has not yet secured the loan and continues to talk to lenders. Private financing is still possible, the source said.

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “If I were to sleep with her, I might get HIV.”- A real estate investor, wary of buying Stuy Town [/vision_pullquote]

But perhaps the buyers’ greatest takeaway from the 2006 deal was the futility of trying to fight the city and Stuy Town’s tenants, whom Kathryn Wylde, head of the pro-business group Partnership for New York City, described as “among the most politically connected in the city.”

“No one who’s thoughtful would go to war with them,” Wylde said.

Even if the buyers could somehow push through their plans, they ran the risk of a public-relations disaster.

“They knew if they didn’t get to the point where it was a win-win for everyone, that wouldn’t reflect well on them,” a source close to Blackstone said.

[vision_pullquote style=”3″ align=”right”] “I realized that to get such a huge mortgage, you need the backing of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.” — Sen. Chuck Schumer [/vision_pullquote]

III. The city

On Oct. 9, Alicia Glen was on a plane from San Francisco to New York when she got a call from her staff. CWCapital was now ready to move forward with a sale of Stuy Town, and it had a buyer lined up.

Glen, the city’s deputy mayor for housing and economic development, had been in on-and-off talks with CWCapital for 18 months and was aware of several suitors. But now, for the first time, a deal looked likely.

That same evening, she spoke on the phone with Jonathan Gray, who runs Blackstone’s real estate business. Gray “really didn’t want to do it unless the city of New York was on board,” Glen recalled. According to her, Gray intended to use patient capital and low leverage, hold the property for a long time, and had a genuine understanding that there is political risk.” This was music to the city’s ears.

Talks began in earnest the following Monday, Columbus Day. From the start, it was clear that any deal would hinge on the buyers committing to keep a fixed number of apartments affordable. According to several sources, Blackstone first proposed a number far lower than the 5,000 ultimately agreed on. “We had some delta,” Glen said. “It was substantial enough that we were all here on Columbus Day having a pretty serious talk.” Blackstone declined to comment on the negotiations.

For the rest of the week, the parties worked at a frantic pace. “There were plenty of night shifts, but remember, I used to work at Goldman [Sachs] so this is not unusual for me,” Glen quipped. Key people in the room: MacArthur, Harmon, Gray, Blackstone’s co-head of U.S. acquisitions Nadeem Meghji, Glen, her chief of staff (and fellow Goldman night shift alum) James Patchett, and City Councilman Daniel Garodnick, a longtime Stuy Town resident and influential tenant advocate.

“We have had meetings with countless real estate entities over the years,” Garodnick told TRD. “This one was different, largely because they were looking to solve problems and to create long-term affordability in the community.”

If stakes were high for Blackstone and Ivanhoe Cambridge, they were arguably even higher for the city. De Blasio made affordable housing a core tenet of his campaign, and his administration has pledged to create or preserve 200,000 affordable housing units by 2025. In fiscal year 2015, the city funded 20,325 affordable units. Reaching a deal to preserve Stuy Town’s rent-controlled apartments – about half the complex is market-rate – could add 5,000 to that tally in a single stroke.

Without a deal, the complex would continue to lose 300 to 350 affordable units per year to decontrol, according to Glen. “You could just see where this was heading,” she said. “This is the mother lode of workforce housing, the largest residential complex in America. If we can’t do something to keep this safe, at least for the people living there, then what are we doing? Why do we even get up in the morning?”

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=”right”] “If we can’t do something to keep this safe, at least for the people living there, then what are we doing? Why do we even get up in the morning?” — Alicia Glen [/vision_pullquote]

Despite the stakes, talks were amicable, sources said. “Once Blackstone was at the table with a significant affordable housing plan and a willingness to satisfy many of the tenants’ top priorities, it became a friendly conversation,” Garodnick recalled.

But the deadline was looming. Blackstone had a first look at Stuy Town until Oct. 19, but if it failed to reach a deal by then, CWCapital could move on to other bidders.

As the talks progressed, the media finally got wind of what was going on. On Oct. 16, Real Estate Finance & Investment, an obscure British trade publication, broke the news that the complex was up for sale. As rumors circulated, reporters began calling Eastdil, CWCapital and Blackstone. Other suitors, who thought they were still in the game, suddenly started hearing that another buyer had all but sealed the deal. And Stuy Town’s tenants were getting anxious.

“By that weekend I felt very uncomfortable,” said one source close to the talks, adding that he put the chances of an agreement at 50/50. “All of a sudden it was a rush. It felt like even towards that weekend it could have blown up.”

Four negotiations were going on simultaneously: Between Blackstone and CWCapital, between Blackstone and the city, between Blackstone and Ivanhoe Cambridge over the terms of their partnership, and between Blackstone and key local stakeholders such as Garodnick, Assemblyman Brian Kavanagh and Susan Steinberg, the head of Stuy Town’s tenants’ association.

On Oct. 19, Blackstone and Ivanhoe Cambridge signed a contract to buy the complex for $5.3 billion, and are set to close by the end of the year. Each partner is putting down about $1.3 billion in equity, leaving about half the purchase to be financed through a loan.

As part of the agreement, they will keep 5,000 apartments affordable for 20 years and will refrain from building any new units or attempting a condominium conversion at the complex. In return, the city will give the buyers about $225 million worth of benefits, through a loan and an uncollected tax. And the buyers have the de Blasio administration’s blessing to sell the complex’s some 700,000 square feet of air rights, which could net them hundreds of millions of dollars.

“We landed many planes at the same time on Monday night,” said another source involved in the talks.

Dan Garodnick speaking at a press conference announcing the deal on October 20. Surrounding him, from left: Bill de Blasio, Brian Kavanagh, Jonathan Gray, Alicia Glen, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer and Susan Steinberg

IV. The tenants

The next morning, an unusually mild one for mid-October, the parties gathered at Stuy Town for a press conference. To those who didn’t know what had transpired behind closed doors over the past week, it must have been quite a sight.

Here was Blackstone, a private equity company that had made a fortune off of foreclosed homes and restructured businesses (among many other things), and whose billionaire founder had once likened the push to raise carried interest taxes to Hitler’s invasion of Poland, being lauded by half a dozen progressive politicians as a guardian of the middle class.

“I know that [Gray] understood from the beginning that there was an opportunity to do something good and lasting here, and he put his heart into it,” de Blasio said. “And I want to thank him for his leadership.”

When Gray stepped up to speak, the scores of onlookers applauded. “We are an asset manager, we invest primarily on behalf of public pension funds, as you’ve heard — teachers, nurses, firefighters, that’s whose capital we invest,” he said. “And those are the very same people who live in this community and what it was intended for when it was originally built.”

Gray added that the years of turmoil at Stuy Town are “definitively over,” prompting some cheers. When he was done, a tenant onlooker mumbled: “that was nice.”

The deal has attracted its fair share of criticism. One politician said he would have liked to see more affordable units created. Many tenants remain miffed they weren’t briefed on the deal until it was signed, or would have preferred a co-op conversion. Many don’t see why an immensely profitable fund manager needs hundreds of millions of dollars in public subsidies. And this week, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer, Kavanagh, Maloney and State Sen. Brad Hoylman wrote an open letter to Gray, voicing concerns over the impact an air rights transfer could have on the surrounding neighborhood.

Still, the four politicians continue to support the deal in general terms, and so, it seems, do most tenants.

“I would say that the residents of the complex are being realistic,” Kavanagh told TRD. “Some residents are not happy with that deal. It depends on your particular circumstances.”

[vision_pullquote style=”3″ align=””] “Some residents are not happy with that deal,” said Kavanagh. “It depends on your particular circumstances.” [/vision_pullquote]

Michael McKee, of Tenants PAC, described the deal as a “mixed bag.” He said that most of the Stuy Town units deemed affordable won’t actually be affordable for middle-income families and lamented that previously deregulated units were not reinstated as affordable. “Blackstone would not be buying this if they didn’t think they would be making money,” he said. “They are not a charity.”

Garodnick believes most Stuy Town residents are simply relieved that things aren’t as bad as they were in 2006. “The alternatives for tenants were quite bad and the community has already lived through that,” he said.

But the goodwill for Blackstone also stems from the firm’s careful PR strategy. From the moment the deal was announced, it portrayed itself as a concerned landlord, willing to listen to tenants and work for the public good. That strategy was on full display at a tenants’ assembly the Saturday after the deal was signed.

The meeting was a far cry from the tumultuous gatherings of 2006. Several seats in the grand auditorium at Baruch College’s Mason Hall remained empty. “This is kind of a non-event,” one attendee said, explaining he was simply there to make sure he understood all the details of the deal.

The plaque dedicated to MetLife’s Frederick Ecker. It was removed in 2002.

After the politicians did their thing, Blackstone’s Meghji spoke, sprinkling in more appeals to local sentiment than a presidential campaigner in Iowa. He recalled how he used to jog through the complex from his Union Square apartment, and pointed out that several Blackstone employees live in Stuy Town. He repeated Gray’s firefighters-and-teachers bit, extolled his company’s integrity, pledged to listen to residents’ concerns (via a newly established website and hotline) and to not abuse capital improvements to hike rents.

“We are really excited about starting this journey with you. We know we need to earn your trust,” he said.

He also addressed an issue that had popped up again and again throughout the meeting: the missing Ecker plaque. “This one actually wasn’t on my list,” he said, “but we will also find that plaque.” That got the loudest applause of the afternoon.