When Brooklyn’s most heralded startup, the online marketplace Etsy, inked a 200,000-square-foot lease at Dumbo Heights in July 2014, many saw it as confirmation of a long-held hypothesis: If landlords provided new office space in the borough, then companies would be willing to sign massive leases at super-high rents.

But since Etsy agreed to anchor RFR Realty and Kushner Companies’ 1.2 million-square-foot redevelopment project, Brooklyn’s office market has gone from underserved to bloated as eager developers head deeper into the borough.

And while some developments — such as Midtown Equities, HK Organization and Rockwood Capital’s Dumbo office complex Empire Stores and Rudin Management and Boston Properties’ tech-focused Dock 72 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard — have seen success, others are facing the cold, hard truth of supply and demand in more untested office markets like Red Hook, Sunset Park and Bushwick.

“There was a perception in Brooklyn that tenants would come as long as it is ‘cool,’” said Whitten Morris, head of leasing in Newmark Knight Frank’s Brooklyn office.

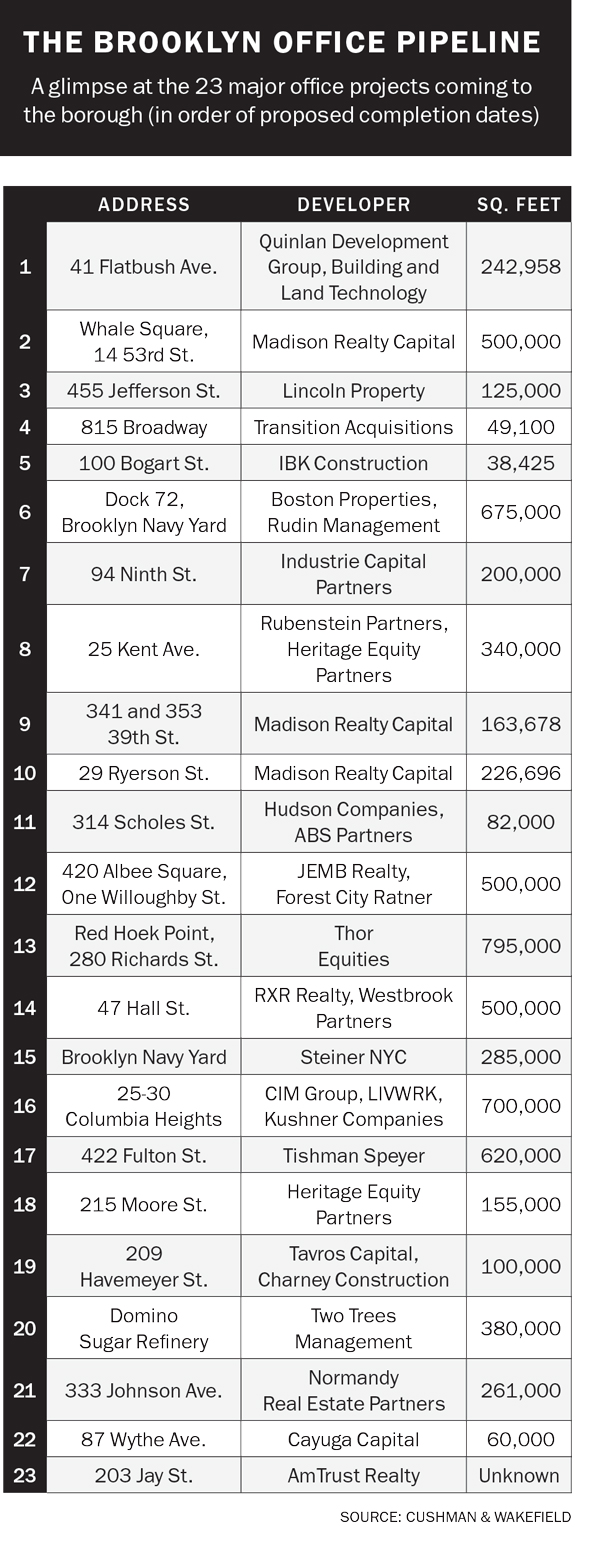

Indeed, the numbers show that developers thought demand for hip offices would take off: There are 23 office projects underway in Brooklyn, which will add roughly 6.9 million square feet to the market by 2020, according to Cushman & Wakefield. The amount of new supply accounts for roughly 20 percent of Brooklyn’s 45 million-square-foot market, whereas in Manhattan, new office supply makes up about 7 percent of the market, Colliers International data shows.

And while leasing activity in Brooklyn stood at 430,000 square feet in the first quarter of 2017 — more than double the volume of a year earlier — it couldn’t keep pace with the 900,000 square feet of new space delivered to the market in early 2017, according to CBRE.

Now, developers are wondering if the borough’s office market can live up to the initial hype. In Red Hook, which was set to house two of Brooklyn’s most ambitious office projects, developers are finding that the demand for logistics spaces outweighs the demand for office.

In May, the Italian real estate firm Est4te Four sold off six parcels of land where it had planned its 1.2 million-square-foot mixed-use Red Hook Innovation Studios project. New Jersey-based logistics firm Sitex paid $110 million for the properties and will use them for industrial purposes.

Massimiliano Senise, a partner at Est4te Four, told The Real Deal that the company was in talks with potential tenants and realized there was strong demand from logistics companies, which require less-costly space than developers would have to build for office tenants.

But Est4te Four’s change in plans isn’t discouraging others. Joseph Sitt’s Thor Equities is moving forward with plans for Red Hook Point, an 818,000-square-foot office and retail complex next to Ikea at 280 Richards Street.

A spokesperson for Thor said that a “limited supply of office alternatives in Red Hook has only made our project more desirable,” but the firm has yet to secure an anchor tenant for the waterfront project, which it began marketing in early 2017. Sources told TRD that the developer wants to line up an anchor before starting construction, and finding a high-paying office tenant is even more crucial to justify the cost of building from the ground up.

A spokesperson for Thor said that a “limited supply of office alternatives in Red Hook has only made our project more desirable,” but the firm has yet to secure an anchor tenant for the waterfront project, which it began marketing in early 2017. Sources told TRD that the developer wants to line up an anchor before starting construction, and finding a high-paying office tenant is even more crucial to justify the cost of building from the ground up.

“I always felt like the Red Hook office market was a little bit speculative,” said Ben Waller, a commercial broker at ABS Partners Real Estate who specializes in Brooklyn office deals. “It doesn’t have all the attributes that everyone wants to live and work in. It would really take a few large anchor tenants for a project [on the scale of the Red Hook Innovation Studios] to get off the ground.”

But even in neighborhoods with success stories like the conversion of Industry City from shipping and manufacturing warehouses into office, a wave of copycats is adding more inventory.

Josh Zegen’s Madison Realty Capital bought the 500,000-square-foot Brooklyn Whale Building in Sunset Park in 2015 and the following year snapped up a pair of former industrial buildings spanning 163,000 square feet across from Industry City. Those properties are now being marketed to office tenants. A short walk away, adhesives maker AP&G started marketing its 165,000-square-foot warehouse to office tenants in 2015, after the company relocated to New Jersey.

Despite the new supply, Zegen said he’s still seeing strong demand in Sunset Park because “it’s one of the cheapest rent markets in New York City.”

“You’re seeing a lot of tenants who are being displaced from other markets in Brooklyn and Manhattan,” he said.

On the whole, Brooklyn’s office availability has increased for the third consecutive quarter, to 18.1 percent, and because of new developments, there are now nine blocks of available space in the market above 250,000 square feet, according to a report from CBRE. By comparison, in Manhattan, which is considered balanced between landlords and tenants, the availability rate stood at roughly 10 percent, according to Colliers.

And two of Brooklyn’s largest office availabilities are in Sunset Park. Salmar Properties’ Liberty View Industrial Plaza has about 400,000 square feet, according to a representative for the firm, and the Brooklyn Army Terminal has about 269,000 square feet, according to its website.

Rubenstein Partners and Heritage Equity Parnters’ 25 Kent

Farther north in the borough, the Brooklyn Navy Yard — which itself will get 1.3 million square feet of new space over the next two years — is seeing more competitive product come online in the immediate area. In 2015, Madison Realty bought a 215,000-square-foot warehouse at 29 Ryerson Street, and the following year, RXR Realty and Westbrook Partners bought the 670,000-square-foot building next door at 47 Hall Street. Both are being converted into office.

The warehouse-office conversion is also common in Bushwick, where a handful of developers are looking to attract large tenants who will shell out the big bucks. And many landlords are having better luck with smaller-footprint tenants, as Bloomberg News previously reported — a sentiment that brokers TRD spoke to echoed.

Normandy Real Estate Partners is converting a warehouse at 333 Johnson Avenue into 261,000 square feet of office, and Dallas-based Lincoln Property is doing the same with a 125,000-square-foot warehouse at 455 Jefferson Street.

Lincoln Property’s project, which is set to kick off leasing this summer, has asking rents in the mid- to high-$50s per square foot — not far off from the kinds of rents tenants will pay in ritzier areas like Dumbo, and roughly $20 more than the borough’s average asking rent of $37.80, according to CBRE.

“They’ve done it in Midtown South in this cycle, where they take the ‘brick-and-beam’-type of building and go from $30 to $50 to $70 to $90 [per square foot] or more than that,” said Jim Stein, a senior vice president at Lincoln Property.

But it’s exactly those types of price-pushing projects that are in danger of being undercut by lower-priced competition in the area, said Alex Robayo of the Brooklyn-based brokerage Ideal Properties Group.

In Bushwick, many longtime owners have kept their warehouses vacant in anticipation of a neighborhood rezoning that could pave the way for residential development. Following a recent community board hearing, the rezoning seems less likely, and now, many of those landlords are offering their spaces at lower rents than new developments, Robayo said. The average asking rent in northeast Brooklyn — which encompasses Williamsburg, Greenpoint and Bushwick — was shy of $42 per square foot during the first quarter, according to CBRE.

“There are so many empty warehouses, and that inventory puts a dent in any large-scale, high-end market because now you have properties going at half the price,” Robayo said.

As availability in Brooklyn grows, one project in particular stands out: Heritage Equity Partners and Rubenstein Partners’ 25 Kent in trendy Williamsburg, a nontraditional office market. The rising eight-story structure is the first speculative, ground-up office building that the borough has seen in decades, and asking rents are in the low $70s per square foot.

Thor Equities’ Red Hook Point

The owners are targeting an anchor tenant to take somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000 of the total 430,000 square feet of office space. Brooklyn hasn’t seen a deal of that size since July 2015, when WeWork inked a 222,000-square-foot lease to anchor Dock 72 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

David Falk, president of the tri-state region for Newmark who is leading the leasing effort at 25 Kent, told TRD there are definitely challenges with being the first to bring a new kind of building to a neighborhood.

“It’s something that doesn’t exist presently in Brooklyn. You have to educate some tenants,” he said. “This doesn’t happen overnight.”

Jeremiah Kane, the New York City regional director at Rubenstein, said he doesn’t think the Williamsburg office market is riskier than it was when 25 Kent was first envisioned.

“In a lot of ways we feel like the risk has diminished,” he said, pointing to the slew of residential and hotel developments in the area. However, Kane said he was not convinced that some of the competing projects in the pipeline will get off the ground.

“Brooklyn is a show-me market,” he explained. “They used to try to sell you a bridge in Brooklyn, and now they try to market you a rendering for a building that will never get built. It’s easy and cheap to create renderings; it’s hard to get a building financed and built.”

Paul Mas, a managing director at JLL, said ground-up, speculative office projects like 25 Kent and Two Trees Management’s Domino Sugar Factory have higher bars to reach than similar ones in established markets.

“They’re trying to succeed like [developers have in] Dumbo,” he said, and noted that tenants looking in more untested markets will “generally want to see a project much closer to completion than [they] might have in Manhattan.”

Mas said that last summer he toured projects in all of Brooklyn’s emerging neighborhoods with the European tech incubator B. Amsterdam, which signed a 100,000-square-foot lease at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He noted that even now, all of the other large spaces they looked at are still vacant, which is “indicative of what’s happening in these emerging submarkets.”

Newmark’s Morris said that developers will have to readjust. “They are changing their expectations and learning a little bit more about the market,” he said.

And until more tenants take a leap of faith into the borough, the success of Brooklyn’s office market will largely rely on proximity to Manhattan.

“Bottom line is Brooklyn is an ascending, young market waiting for its ‘Google’ moment,” Morris noted, “but in the meantime it will certainly experience fits and starts as it matures.”