“It’s 10:30 at night, and I’m in a restaurant. My phone is ringing, no caller ID. I answer the call. It’s Larry Ellison.”

Eighteen years on, Kurt Rappaport said he still recalls exactly how the phone call that changed his life went down. He continued:

“[Ellison] says, ‘I’m flying in tomorrow. I’ll land in Santa Monica around 10:00 a.m. I’d like to be on Carbon Beach. My friend, David Geffen, lives on Carbon Beach. If there’s anything we can see, that would be great.”

Rappaport had recently co-founded Westside Estate Agency and was already a successful agent. Ellison, though, was the multibillionaire chief of Oracle, a tech titan who raced yachts in his spare time.

“I had a mental encyclopedia of properties that are on the market,” Rappaport said. “I said, ‘Two-two-four-four-five PCH. I’ll meet you there at 10:00 a.m.’ And he said, ‘If there’s anything else to see, let’s take a look at that as well.’”

(Rappaport’s memory was not entirely perfect. He later confirmed the listing was, in fact, 22334 PCH.)

One hiccup: The listing wasn’t Rappaport’s. It was held by veteran agent June Scott.

“She was a character, like a typical old dame lady of Beverly Hills,” Rappaport said of Scott. “So, it’s 10:30. It’s probably too late because June was too old, in the twilight of her career. But I tried calling her anyway. I left messages everywhere. Couldn’t reach her.”

The next day, Rappaport woke up at 5:30 a.m. and got Scott. He explained that he was bringing Ellison for a showing and would be coming to pick up the keys.

“She said to me, ‘Well, can you see if Barry could come Sunday or Monday.’ I said, ‘First off, it’s Larry, not Barry. And he’s coming in the morning.’ I begged and I pleaded. She politely said, ‘No, honey can’t do it.’

“This,” Rappaport scoffed, “is the way agents do business.”

But Rappaport was relentless. He went to the property, he pried open the door (Scott relayed she neglected to turn on the security system) and showed it to Ellison at 10:00 a.m. The deal was put together by lunch.

“And that’s how I have to be on the ball,” Rappaport said. “You can’t teach somebody court awareness, when there’s two seconds left, you’re down by two points. And instead of taking the shot, you see the guy in the corner, and you fake to them and then take your shot.”

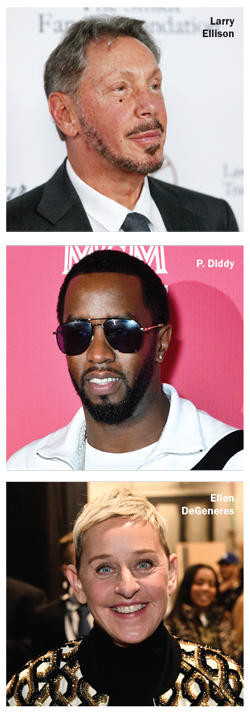

That single-mindedness in pursuit of a sale is characteristic of Rappaport, who has long sat at the top of the heap of luxury agents in California — and make no mistake, it’s a heap full of colorful characters with envious Rolodexes. But even those rivals would grudgingly admit his dominance and marvel at a client list that includes moguls such as Ellison, Geffen and Jeffrey Katzenberg, superstar athletes such as Tom Brady and celebrities such as Ellen DeGeneres.

Rappaport, however, would take issue with even that characterization.

He sees himself not as atop other agents but in a different realm from them altogether. He measures himself by the captains of the universe he sells homes to.

“The thing to know about Kurt,” said Michael Nourmand, of Nourmand & Associates, “is that he is who he represents.”

But Rappaport is still far from his clients’ level of money and power. And it’s not clear if he’d risk his salesperson’s perch to truly enter such an orbit.

Sixteen at Spago

Over lunch at The Palm in Beverly Hills, Rappaport is interested in telling his story but self-conscious about how he will come off. Well over six feet tall with a generous head of hair, he’s clad in all black, sits ramrod straight and precisely pushes away his plate when he wants to make a point. He is polite to waitstaff but a bit miffed the hostess didn’t know who he was.

The way he tells it, Rappaport possessed an adult mind at a very young age, existed in a playground of the rich and famous and had the Gen X mindset to be bored with most of it.

An only child of divorce, Rappaport grew up with his mother in the San Fernando Valley. At the age of 12, he moved to Westwood to live with his father, Floyd Rappaport, an entertainment lawyer at the august firm of Mitchell, Silberberg & Knupp.

His dad’s career allowed a teenage Rappaport to rub shoulders with the likes of Robert Evans, the producer of “The Godfather” and “Chinatown” and a legendary philanderer and party animal.

“I sort of grew up in Robert Evans’ screening room, and we’d go there on Friday and Saturday nights and meet the most interesting people on the planet.” Rappaport said. “A lot of them were talking about real estate and houses.”

Those conversations with the glitterati impressed on Rappaport that real estate didn’t have to be the domain of hucksters and has-beens but could be “another form of art or creative expression,” akin to selling an impressionist painting or modernist sculpture.

He began reading Ruth Ryon’s L.A. Times “Hot Property” column and put his baseball fanaticism to good use, memorizing addresses, prices and square footage as if they were batting averages.

“A lot of the kids I grew up around who came from privilege were not terribly motivated or evolved,” he said. “When I was in high school, I was 16 in Spago. All my friends were much older. I wasn’t going to keg parties.”

He wasn’t totally above a childish prank, though. Home after a tennis match at the age of 18, Rappaport received a phone call from KTTV Channel 11. The Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega had just been captured and flown to the U.S. to stand trial, and the station, scrambling to put together a segment, was trying to reach the Panamanian consulate. Someone had misdialed.

Without missing a beat, Rappaport confirmed it was the consulate and that he was a certain “Arturo Valdez” from the USA-Panama Friendship Council. The station invited Rappaport on the air, and Rappaport bought a mustache that he applied to his face with Spearmint gum.

Without missing a beat, Rappaport confirmed it was the consulate and that he was a certain “Arturo Valdez” from the USA-Panama Friendship Council. The station invited Rappaport on the air, and Rappaport bought a mustache that he applied to his face with Spearmint gum.

He appeared on TV, waved his arms around and spoke with an accent about what Panamanians thought of Noriega. “They see right through him, like a clear curtain,” he said on air. His stunt got him a writeup in the L.A. Times, which reported that other stations had inquired about booking him.

Recalling the prank today, Rappaport said, “I got more confident the further

I went.”

Fighting to the top

By 19, Rappaport had dropped out of USC, left an entry-level job at William Morris and got his real estate license. He started out as an agent at Merrill Lynch Realty in Beverly Hills, but when recalling those days, he exudes a palpable, almost primal disgust, comparing the high-pressure sales tactics he was taught to the desperate characters of “Glengarry Glen Ross.”

He quickly made his mark: By 22, a Times article noted his representation of Hollywood madam Heidi Fleiss.

“Kurt was a lot younger than me, but he knew a set of people I didn’t know,” said Victoria Risko, who partnered with Rappaport early in his career. “He also knew the properties because he grew up in Los Angeles.”

The two moved together to work for Fred Sands, perhaps L.A.’s premier luxury broker of the 70s and 80s. Sands’ “quotes and ideas could move real estate,” rival broker Mike Glickman told the Times.

But Rappaport viewed Sands as running a bloated outfit.

“The right hand didn’t know what the left hand was doing,” Rappaport said. “And no one could make a decision.”

The clash between the grizzled eminence and the brash upstart became hot industry gossip. Rappaport sued Sands, claiming an office administrator — who Sands was allegedly dating — kept asking Rappaport for confidential client information.

“I sued and I won,” Rappaport said. He was unhappy to retell the feud but made sure to note, “I later bought the building where Fred Sands was.”

Rappaport decamped to work for Stan Herman & Stephen Shapiro.

“When I met Kurt, he was 25 going on 50, maturity wise,” Shapiro said. “He possessed an incredible knowledge of Beverly Hills. You could read off an address, and he could talk about the property and its history. And he worked his ass off.”

For his part, Rappaport admired Shapiro’s posse, which included Hard Rock Café founder Peter Morton and film producer Steven Tisch.

“His best friends were his clients,” Rappaport said. “He was kind of a version of what I was.”

By 1999, as Shapiro recalls, he was butting heads with Herman, who was moving into semi-retirement and wasn’t sure if agents really needed computers. Shapiro decided to bet on Rappaport, and the duo formed Westside Estate Agency. They decided on a dynamic that’s still in place today.

“I do the management,” Shapiro said. “He sells.”

The new establishment

How many blockbuster sales agents actually make, and what commissions they and their firms generate from those sales, is an inexact science. (Some brokerages self-report data to analytics firm Real Trends, though the data is not independently vetted, and Westside and other leading firms have declined to disclose their figures.

9388 Santa Monica Blvd.

Over the last three years, The Real Deal ranked the top L.A. agents by sales volume, meaning if an agent represents the seller of two $5 million home sales, they compile $10 million in sales volume.

In 2018, charting sales recorded on the Multiple Listings Service plus “off-market” deals verified by TRD, Rappaport ranked first with $627 million in sales volume. Chris Cortazzo of Compass placed second with $530 million in sales. For 2019, Rappaport was again first, with $513 million in deals, again followed by Cortazzo. (Cortazzo declined comment for this story).

This past year, TRD’s analysis was limited to deals in the first six months of 2020 recorded in the MLS. Rappaport was behind Cortazzo for on-market deals, but observers said he would take the top spot had his off-market deals been taken into account.

One such transaction is Jeffrey Katzenberg’s $125 million sale of his Beverly Hills home to WhatsApp co-founder Jan Koum, one of the five biggest-ever single-family home sales in California. Rappaport also advised David Geffen on a $34 million Beverly Hills land sale in November, after brokering a $68 million home buy for Geffen in June.

Another mega-client is DeGeneres, who has become a major luxury real estate player in Southern California. Rappaport claims to have done 25 deals with the talk show host. Rappaport warmly discusses these clients, and others like former CNN personality Larry King, who the agent sits with at Dodgers games, and former L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa. The clients, in turn, enthusiastically praise Rappaport.

“He is the consummate professional in every respect,” Villaraigosa said.

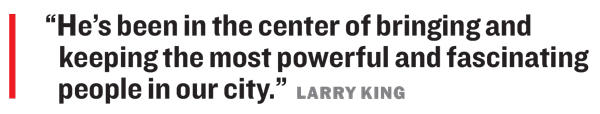

King said, “He’s been in the center of bringing and keeping the most powerful and fascinating people in our city.”

Haters hate

If you’ve been skimming this article to read Rappaport shit-talk rivals, here’s the best you’re going to get.

Rappaport on Jeff Hyland: “We’re just different. I don’t like speaking poorly about anyone.”

(Several messages with the normally chatty Hyland for this article went unreturned.)

Rappaport on deals about his properties he owns: “I was living in homes that other agents couldn’t even sell.”

Rappaport on how he’s seen by other agents: “We used to be in a world where people looked up to success.”

Asked their opinion of him, agents mostly took the high road.

“He may have the highest sales volume in L.A.,” said David Offer of Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices California Properties. “But there’s no way to really know for sure.”

Carl Gambino of Compass praised Rappaport as a mentor.

Jeffrey Katzenberg sold this Beverly Hills estate to Whatsapp co-founder Jan Koum, in a $125 million deal brokered by Rappaport

“He allowed me to step into his world,” Gambino said, “which helped me to become a better agent.”

For many agents, their beef with Rappaport isn’t that he’s No. 1 and says so. It’s that he takes his success so seriously.

Real estate is a second or third career for many. Risko was an astrophysicist. Branden Williams was an actor. Fredrik Eklund had a stint in porn. Stan Herman, Shapiro’s former business partner, was as well known for creating a backgammon club with Hugh Hefner as he was for selling.

In Los Angeles, being an agent can be more clubby than competitive. Success means starring in “reality” television shows, or heading teams of a few — or few dozen — agents at national brokerages. Rappaport views such pursuits as compromising client privacy and hurting sales.

Compass’ Ron Wynn once feuded with Rappaport over a Brentwood home sale but claimed he has nothing personal against him. Still, he said he feels Rappaport is too serious.

“Jade Mills [of Coldwell Banker] is approachable, light-hearted and cooperative,” Wynn said. “A very common thing is to have a price party. Get a bunch of people out and put what you think will be the price of the property in a hat. Jade will do that.”

Another agent put it this way: “I’ve heard brokers say I want to be Jade Mills. I haven’t heard that with Kurt.”

(Mills, like most agents, would not discuss Rappaport. She responded through a spokesperson: “Jade works extremely well with all brokers on behalf of her clients to help them achieve their real estate goals.”)

Family matters

Google “Kurt Rappaport” and images splash across the screen of him with Canadian fashion model Sarah Mutch. Rappaport married Mutch in 2017 in a star-studded wedding at his 15,000-square-foot Malibu mansion that was attended by P. Diddy, Ryan Seacrest and DJ Khaled. But less than two years later, Rappaport filed for divorce and sued Mutch for extortion. His scathing complaint was followed by a cross-complaint from Mutch and an eventual settlement for an undisclosed amount.

Rappaport was adamant about not discussing his private life. But Mutch’s cross-complaint bears mentioning, as allegations in it showcase Rappaport’s obsession with his work. Regarding the wedding, Mutch’s lawyers alleged that it “was just as much a business event as it was a wedding. The house they married was on the market for $100 million. Rappaport used the wedding to showcase this house to his wealthy client and friends.”

Five months after the wedding, Rappaport sold the home to Canadian billionaire Daryl Katz for $85 million.

In early December, Rappaport suffered the loss of his son, Jake, who was 24. He declined to comment on the death, except to say, “Nothing matters except family and loved ones. Don’t ever take loved ones for granted. Spend as much time as you can with them.”

America’s pastime

Since meeting Ellison that day in Malibu, Rappaport has been periodically trying to transcend home sales.

Rappaport and Ellison eventually did 35 deals together. But beyond the hundreds of millions of dollars in sales volume and millions in commissions for Rappaport and Westside, Ellison meant something more: a true master of the universe who treated Rappaport as not just the guy to sell him a sun-filled mansion but a fellow creator of wealth.

“I explained to him my love for Malibu and why I thought it was undervalued compared to other coastal cities across the globe,” Rappaport said. He and Ellison “changed the pricing structure” of Malibu, bringing high-end shops, restaurants and hotels to a city where “the retail was surfboard and T-shirt shops.”

Rappaport’s quest to be more like the Ellisons and Geffens of the world can be a hard-to-define ambition. He has dabbled in some smaller commercial investments, including a Soho House-type club that has yet to be completed. But, there is one specific end goal — owning a Major League Baseball team.

He described becoming a baseball owner as, “having a seat at a private club with some very interesting people.”

In July, Rappaport said he wanted to buy the New York Mets. But as negotiations proceeded, Forbes reported that Rappaport had a net worth of just $250 million and warned he would need multiple business partners to make a deal work.

Come September, infamous hedge fund manager Steve Cohen — a Rappaport client — bought the Mets for $2.4 billion. Cohen, who was the inspiration for Bobby Axelrod in the hit Showtime series “Billions,” is worth at least $15 billion, according to Forbes. That makes him one of the wealthiest league owners, but it’s certainly a billionaires’ club. The Steinbrenner family, longtime owners of the New York Yankees, are worth $3.8 billion.

Rappaport would not discuss his net worth. When pressed, he waxed philosophical about how at his level of wealth, the specific amount of money doesn’t matter. Besides, he argued, he can assemble a team of rich friends to buy a baseball club — or anything else.

But Rappaport does have a regret: “I wish I had bought more.” His current and former portfolio includes two-dozen luxury properties in Beverly Hills, Bel Air, Malibu and Brentwood, including a Brentwood home he bought from former Viacom executive Frank Biondi in 2018 for $16 million and said he plans to move into later this year.

But Rappaport’s selling instincts can often clash with his desire to assemble and hold trophy properties.

“He often doesn’t build these homes in order to sell,” said Scott Mitchell, Rappaport’s architect on the Malibu house that sold to Katz. “Then someone comes along with a seductive number, and he can’t say no.”

How badly Rappaport would want to own a team is unclear. In 2009, Dennis Gilbert, agent to baseball stars of the 1980s and 90s, was the lead investor to buy the Texas Rangers with Rappaport an investment partner.

“We had a handshake agreement to buy the Rangers,” said Gilbert, now an adviser to Chicago White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf. “But the owner at the last minute decided to go into bankruptcy and we decided to pivot.”

The Rangers play in Arlington, on the outskirts of Dallas, and Rappaport was prepared to move to Dallas, seeing a real estate opportunity outside the Rangers’ ballpark.

Gilbert has vouched for Rappaport to owners like Reinsdorf. “He’s got the resources, and passion and business acumen,” Gilbert said.

“I wouldn’t see it as a hobby,” Rappaport said, “but a real business. A business that can be something of a love with a lot of interesting parts surrounding it, a media part, an entertainment part.”

When reminded that the Angelos family is rumored, again, to be selling the Baltimore Orioles, Rappaport nixed the idea of moving to Baltimore.

They do have a “great fan base,” he allowed.

Rappaport may buy some more property, or a baseball team, or something else. Or he might just spend another 25 years racking up hundreds of millions of dollars in mansion deals, alone at the top of a hill, staring at mountains.