Just a few years ago, it seemed that Tunisian fashion designer Max Azria was at the top of his game. Kim Kardashian, Heidi Klum and Angelina Jolie were wearing his signature slinky dresses, and his empire, which began with just one boutique in Los Angeles, had expanded to include 700 freestanding boutiques and shops-in-shops at top department stores across the globe.

That all came crashing down in March, when his fashion label, BCBG Max Azria, filed for bankruptcy protection and announced it would close 120 of its stores. Behind the scenes, Azria’s business was laden with debt, which he’d refinanced with more expensive debt, including a $135 million cash infusion in 2015 from affiliates and clients of Guggenheim Partners, the investment banking firm.

Eventually, the company buckled under the burden of its commitments, and its investors couldn’t see the sense in throwing more good money after bad.

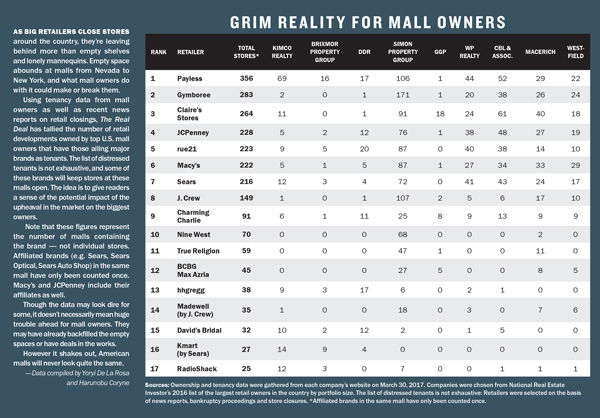

BCBG is just one of many retailers to crumble this year. Macy’s, Sears, Payless, American Apparel, the Limited, Wet Seal and the electronics chain hhgregg have all announced store closures or bankruptcies since the beginning of 2017 in a great collapse of the retail dominoes. In a statement Feb. 24, JCPenney said it planned to shutter 130 to 140 stores and two distribution facilities, citing slower consumer traffic and muted sales. Its announcement came just weeks after Macy’s and Sears announced their own store closures.

As of press time, Gymboree, the struggling children’s clothing retailer backed by Bain Capital, was reportedly preparing to file for bankruptcy as it faced a June 1 interest payment on its debt.

“I think retail is fucked, plain and simple,” said Billy Macklowe, the head of major New York development firm the William Macklowe Company (and son of famed developer Harry Macklowe), speaking at the Haute Residence luxury real estate summit at the Core Club in late April.

Macklowe pointed to empty storefronts on Manhattan’s Madison and Fifth avenues, as well as in Soho. Tenants are looking for lower rents, and “the first landlord that blinks” will reset the market, he said. “Every retailer will pounce and smell blood in the water.”

The collapse of so many companies could have far-reaching consequences for retail-driven real estate owners and investors across the country, who, seeing the demise of their tenants, must backfill space or risk seeing their own bottom lines deteriorate.

Many of the retailers were backed by private equity. “The private equity guys who do these deals declare a new bankruptcy every day,” said Howard Davidowitz, chairman of national retail consulting and investment banking firm Davidowitz & Associates. “It’s a moment of reckoning. Reality has arrived, and it’s going to be very, very bad for the guys in the brick-and-mortar business.”

Edward Dittmer, vice president of CMBS at Morningstar Credit Ratings, added: “If you’re faced with decision right now to invest more cash with all negative news going around, you probably won’t.”

Insiders say the retail collapse will result in winners and losers — not everyone is going down. It’s survival of the fittest.

Azria, who appears to be on the losing side, is already feeling the pain. The designer recently defaulted on $34.6 million in CMBS loans attached to a 601,979-square-foot portfolio of Los Angeles warehouses used to house BCBG stock. Per the bankruptcy filing, the warehouses will sell in a court-supervised auction in May. If they receive no acceptable bids, Azria will attempt to negotiate a debt-for-equity swap with lenders. BCBG, which leases the warehouses from its founder, reportedly owes its lenders close to $500 million.

The expiration of a wave of CMBS, inked pre-financial crisis, is likely to result in more Azria-style casualties in the next year.

For instance, about $29.82 billion in loans securitized by CMBS issued since 2010 could be affected by JCPenney’s store closures alone, according to investment research firm Morningstar. The research firm also identified 17 CMBS loans with a combined balance of $454.6 million that have exposure to hhgregg stores slated for closure.

“It’s an impending disaster for giant money,” Davidowitz said.

In his annual letter to shareholders last month, Vornado Realty Trust’s famously brash CEO, Steve Roth, sounded like he was forecasting the retail apocalypse.

“I don’t believe we can grow our way out of this mess,” he said of the string of retailer bankruptcies making headlines. “I believe the only fix for brick-and-mortar retailing is rightsizing by the closing and evaporation of, you pick the numbers, 10 percent, 20 percent, 30 percent of the weakest space. This very painful process will surely take more than five years. It will also create enormous opportunity for those with the capital and management platforms to feed on the carnage.”

Roth is not alone is seeing a potential upside for vulture investors.

Hedge funder Jason Mudrick, whose Mudrick Capital Management focuses on distressed investments, recently told Bloomberg that retailers’ problems are here to stay.

“This is a forever trend,” Mudrick said on Bloomberg TV. “When you think about how things are going to look 10 years from now, or 20 years from now, our parents will be dead, our kids will be adults — you think more people are going to be shopping online or less? This is the Amazon effect, and it’s here forever.”

The party line

Mall owners, who are arguably the most exposed to the retail crisis, are taking a sunnier approach to assessing it.

“This whole narrative is way overstated,” Stephen Lebovitz of CBL, one of the U.S.’s largest mall operators, told The Real Deal. “The number of malls that have actually gone away is really small — it hasn’t happened.”

Sandeep Mathrani of GGP quipped: “It’s like I always say, the Romans had a bazaar to go to, and the aliens thousands of years from now will have one, too.”

Sandeep Mathrani of GGP quipped: “It’s like I always say, the Romans had a bazaar to go to, and the aliens thousands of years from now will have one, too.”

Indeed, the early days of the crisis have revealed a stark bifurcation in the ramifications for Class A mall landlords, many of whom say they’ve actually benefited from the rollover of struggling retailers’ leases, and for those lower on the pecking order.

In many cases, Class A mall owners have hustled to attract more interactive replacements for anchor tenants. These alternatives have helped them boost traffic and occupancy levels and better cater to the needs of younger and wealthier customers.

Lebovitz pointed to a renovation recently completed by CBL at the CoolSprings Galleria in Nashville. It bought a Sears department store out of its lease and replaced it with a Connors Steak & Seafood, American Girl, H&M and Kings Bowling and Entertainment. “When you add up all the sales now, it’s four to five times what Sears was doing previously,” he said.

Similarly, in a December earnings call, Mathrani told analysts his company had more than overcome the $180 million of aggregate rent loss and 6 percent of occupancy loss from tenant bankruptcies since 2014. “The investors didn’t even feel a blip,” he said.

He pointed to a roster of new, experiential tenants signed by GGP, including 50 movie theaters across the portfolio, Dave & Buster’s, iFly Indoor Skydiving and a variety of fitness-center concepts.

Restaurants have also played a big role in replacing anchors. In 2011, restaurants made up about 6 percent of GGP’s portfolio. Today, that’s 13 percent.

The company is not alone in seeing that trend. In the first nine months of 2016, food-hall growth increased by 37.1 percent year over year nationwide, according to a November report by Cushman & Wakefield. Cushman said restaurants accounted for 25 percent of growth across all retail concepts it had been tracking across the country since 2007.

GGP has also been touting its newest anchor tenant, KidZania, a massive educational mini-city where children ages 4 to 14 role-play more than 100 professions, from board member to baker and doctor to truck driver. The mall operator recently announced that the retailer was coming to its American Dream Meadowlands mall in East Rutherford, New Jersey (see story on page 16). It will be the first U.S. location for KidZania, which was founded in Mexico.

KidZania USA CEO Keith Rubenstein claims the presence of the brand in a mall can result in significantly increased traffic. He predicted that KidZania would bring at least 500,000 visitors — maybe 1 million — to American Dream Meadowlands when it opens.

GGP’s focus on replacing traditional anchor tenants with entertainment-driven tenants has helped its bottom line, since old anchors were paying such low rents, Mathrani said. It also helps with foot traffic. “Traffic has increased in our portfolio from 2015,” he said, noting that GGP measures traffic through cameras, parking apps, Wi-Fi tracking and website visits. “We actually have a shortage of inventory in our portfolio to meet the demand from retailers, and are meeting some of that demand by acquiring some real estate within our portfolio.”

Conor Flynn, the CEO of major mall landlord Kimco Realty Corporation, echoed those sentiments in Kimco’s Q4 earnings call.

“The steady drift of supply [from retailer bankruptcies] is actually relatively healthy for us, as we’re are able to recapture boxes that are below market and reposition them with best-in-class retailers,” he said.

Even if GGP and its ilk do lose more tenants than expected, Mathrani said, it will have plenty of time to strategize alternative uses. “It takes a long time for retailers to die,” he told The Real Deal. “They seem to live past their useful life for longer than one would anticipate.”

A state of denial

For every Class A mall repositioned by a mega-REIT, there will be a Class C mall that falls into obscurity and ultimately shutters, experts said.

There are several basic issues at play, they explained. For one, with 24 square feet of U.S. shopping center space per capita, the country is vastly overretailed in comparison with other developed countries. Then there’s the challenge posed by online shopping. Finally, consumers went into frugality mode during the last recession, and they never really came out.

Max Azria with his wife and partner, Lubov Azria

“The dead and dying mall is an absolutely true thing on one end of the spectrum,” said Garrick Brown, Cushman & Wakefield’s director of retail research for the Americas. “The real question is the other end. A malls survive no problem, A-plus malls make out, C and D malls are where the disasters are. The question mark is the middle.”

Some industry insiders said that even the mega-REITs will suffer temporarily once mall closures begin to happen en masse.

Many major retail owners have sold or spun off their weaker properties in a bid to avoid downward drag. Simon Property Group spun off its smaller enclosed malls into an independent, publicly traded REIT, Washington Prime Group, for instance. Some of those properties could be repositioned for alternative uses as anchor tenants fall away.

“In the be-careful-what-you-wish-for department, we made the prescient call four years ago that retail was in secular decline and acted on that by selling our [17] malls, spinning our strips into Urban Edge Properties, while retaining and even growing our flagship street retail in Manhattan,” Roth said in his letter.

“If anyone was shocked that Sears had concerns, they were living under a rock,” said Alexander Goldfarb, an analyst at Sandler O’Neill. “The big guys have seen this coming for a long time, and they worked hard to reinvent themselves.”

Some say companies such as Simon and GGP are in denial.

“They’ve been smoking something illegal for a long time. They’ve been in a state of denial, living in their own world for years, saying everything is okay,” Davidowitz said. “You hear all of this bullshit from these guys — ‘Oh, we have a church in the mall now, and nine people came’ — but the fact is there are too many malls. No one is going to escape completely unscathed.”

Even Fifth Avenue retail doesn’t seem to be immune from the crunch. In April, Ralph Lauren said it would shutter its Polo flagship location as part of a cost-cutting spree to strengthen the business.

Vacancy rates on Fifth Avenue between 42nd and 49th streets reached a high of 31 percent last year. And eight of the 11 Manhattan retail neighborhoods tracked by Cushman & Wakefield saw availability rates climb between 0.6 and 8.2 percent. Major Fifth Avenue landlords such as Joseph Sitt’s Thor Equities are also feeling the pain. There’s been speculation that vacancies are putting pressure on the company’s bottom line.

Roth conceded that, even though he was hanging on to Vornado’s Fifth Avenue properties, there would still be a blip.

“Of course, even we are not immune,” he said. “It’s only to be expected when a tenant’s basic business model is being threatened that they hunker down rather than step up. For flagship retail, this is a pause, a cyclical bump. For everybody else, it is secular disruption.”

But those most susceptible to the retail upheaval appear to be owners of secondary retail centers nationwide, typically individuals or smaller firms, who don’t have the balance sheet to reinvigorate their properties.

“If they’re already in a death spiral, they won’t have the capital they need to save their centers,” Brown said.

While department stores typically pay the lowest rents in the mall, the loss of one can have more far-reaching effects than is immediately clear. Other tenants may even have co-tenancy provisions that allow them to wriggle out of their leases or renegotiate the terms if the anchor space is vacated or changes hands to another use. It can also have ramifications for traffic to the mall, impacting other retailers’ sales.

That’s especially true when malls are home to more than one major troubled anchor. “While losing one anchor may not be drastic if cash flow can absorb the loss, two or more anchors leaving can be the beginning of a downward spiral,” analysts from Morningstar wrote in a May report.

That’s especially true when malls are home to more than one major troubled anchor. “While losing one anchor may not be drastic if cash flow can absorb the loss, two or more anchors leaving can be the beginning of a downward spiral,” analysts from Morningstar wrote in a May report.

Morningstar has identified several malls with even more than two beleaguered anchors that will be under significant pressure from bankruptcies. In Pennsylvania, for instance, the Wyoming Valley Mall’s roster of tenants includes Macy’s, Sears and hhgregg.

In the case of the Hudson Valley Mall in upstate New York, former owner PCK Development, a Liverpool, New York-based firm, lost both JCPenney and Macy’s as tenants within the space of one year. It proved a nearly impossible obstacle to overcome.

When the property, which was managed by CBL, sold late last year to Georgia-based Hull Property Group, it traded at an 89.2 percent discount to its original appraised value.

So why would anyone buy such a beleaguered asset?

Speaking at a community meeting, Hull executives reportedly told locals that they’d acquired the property to put their own company on the map. If they could turn around the fate of a property with such an uphill battle ahead of it as the Hudson Valley Mall, they could do anything.

“For us, our little company, if we can show Wall Street that we can make it in Pennsylvania, or Indiana, and particularly if we can make it in New York…” James Hull, managing principal of the company, said at the meeting. “To get into the deal flow in Wall Street is very important. To be able to even break even here, it will do a lot for our company.”

Still, turning around a quickly declining properties is sometimes impossible.

“It’s like the Roach Motel,” Brown said. “Once you go in, you’re not coming out.”

(To view a ranking of Manhattan’s most valuable retail leases, click here)