Billy Zeng left his native Taishan in southern China in 1998 and moved into a rent-stabilized apartment in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Like millions of other Chinese expats who come to the United States in search of new opportunities and a different lifestyle, he didn’t look back.

Zeng, who moved to be closer to his family in New York, took a job as a building engineer and, within four years, was able to buy a $400,000 house in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, he said. Nearly 15 years later, his daughter resides in the two-bedroom home, while Zeng remains in the same Chinatown apartment.

Sitting on a bench in Chinatown’s Columbus Park in September, the grinning man in his early 50s pulled out his phone and flicked through the Realtor.com app.

“These homes here are getting unaffordable,” Zeng told The Real Deal in Mandarin as he scrolled through a map of Lower Manhattan with a sea of red dots indicating condominiums that start at $1 million. “And these are just apartments,” he added.

In this sense, Zeng, who works with local landlords on a contract basis, is typical among New York’s growing community of Chinese immigrants — the pursuit of real estate is a major focus in his daily life.

As of 2015, there were 574,886 China-born New Yorkers, up from 483,886 in 2000, according to the latest U.S. Census Bureau data. They are the second-largest immigrant group in the city, behind Dominicans, but that is bound to change in the next few years, the numbers show.

Though difficult to ignore, the underbelly of New York’s Chinese real estate scene can be surprisingly opaque. The housing market for Chinese immigrants in New York — heavily concentrated in Lower Manhattan, on the border of Sunset Park and Bensonhurst and in Flushing, Queens — is now worth tens of billions of dollars, according to some industry estimates. But more specific breakdowns are virtually impossible to calculate or find.

And in recent years, that real estate market has been increasingly fueled by the influx of wealthy Chinese nationals, who now have easy access to New York City through the federal EB-5 visa program (though that could change with the program’s future in limbo).

And in recent years, that real estate market has been increasingly fueled by the influx of wealthy Chinese nationals, who now have easy access to New York City through the federal EB-5 visa program (though that could change with the program’s future in limbo).

Unlike the city’s more seasoned Chinese immigrants — many of whom first settled in Chinatown and later flocked to Flushing — new buyers are increasingly looking in prime Manhattan neighborhoods, including Midtown and the Upper West Side, in some cases paying all cash for condo units. Extell Development’s One Manhattan Square and the Oosten in Williamsburg, for instance, are targeting China’s upper middle class with condos that start at the $1 million mark.

This demand for property among Chinese buyers has created something of a parallel economy with its own language, customs and family-focused business models. And serving this economy is an army of brokerages, property firms, banks and listing services employing thousands of people.

It’s an industry that doesn’t always operate by the same rules as New York’s more traditional real estate scene. Business is almost always conducted in Chinese, while some of the practices that have traveled over from China clash with American laws and regulations, according to sources. These invisible barriers explain why the real estate industry serving Chinese immigrants remains an enigma, even for many who consider themselves experts on the city’s real estate market.

Firms that dominate other parts of the city, including the Corcoran Group [TRDataCustom] and Halstead Property, have far less reach in Chinese communities. Meanwhile, many of the institutions that have a tight grip on these markets, such as Winzone Realty and Abacus Federal Savings Bank, are virtually unknown beyond their home turfs.

But those two worlds are beginning to overlap.

“Even 10 years from now, I believe there will be more Chinese buyers,” said David Chou, a 26-year-old broker at NY Best Homes Realty, a small Great Neck-based firm. “New York has been a world-class destination for a hundred years, after all. And the Chinese, our comfort and desire in owning a home goes back thousands of years.”

Chinese-American dream

While New York may be a city of renters, homeownership is a must for many of its Chinese immigrants, largely due to customs that have carried over from mainland China.

“For young people, the idea is you have to have a home to start a family,” Min Zhou, a UCLA sociologist who has written books about Chinese-Americans and New York’s Chinatown, told TRD. “They don’t like the idea of renting. It’s a cultural tradition.”

China has one of the world’s highest homeownership rates — between 80 and 90 percent, according to some estimates — well above the 65 percent average in the States. A 2003 study by public-policy scholars Gary Painter, Lihong Yang and Zhou Yu noted that the homeownership rate among Chinese-Americans was 18 percentage points higher than among white households, after controlling for income and housing market trends. There is an idiom in Mandarin, “An ju le ye,” which translated to English means that when one has a cozy and safe environment, everything else in life will thrive.

Union Street in Flushing

But Chinese immigrants in New York, and elsewhere in the States, have additional incentives for buying homes. On top of achieving a certain status and quality of life in Chinese society, there is also the impetus of making it as an immigrant and “achieving the American Dream,” UCLA’s Zhou told TRD. In order to achieve that dream, middle- and low-income Chinese immigrants are willing to “put in everything and sacrifice their current leisure,” she added, noting that many live in crammed quarters and save for five to 10 years with plans of buying a home.

And while it’s not uncommon for Americans from all ethnic backgrounds to get help with a down payment from their parents, many Chinese immigrants take it to another level with the custom of “gift money.” Prospective homebuyers who can’t afford a down payment or high monthly mortgage payments often pool money from parents, siblings, aunts, uncles and cousins.

There are generally no contracts, interest payments or guarantees, and full repayment in some cases isn’t necessarily expected, according to Zhou. “When you are [borrowing] money from relatives, the payment schedule is fairly informal,” she said. “My brother asked me to loan him thousands of dollars, and I just loaned it to him. It’s more of a family obligation thing.”

Sicong Yu, a 33-year old health-care employee who moved to the U.S. when he was 11, borrowed money from his brother and father for a $150,000 down payment on a $250,000 Staten Island condo. Without their help, he said, he wouldn’t have been able to afford the place.

“I will pay them back as soon as possible,” Yu told TRD, noting that his relatives don’t expect any interest in the meantime.

Financing the way

Many Chinese homebuyers still face the hurdle of securing a mortgage once they have the down payment covered. Cultural and language barriers only add to the difficulties, and many Chinese immigrants struggle with the rigid rules of the American mortgage system, including income requirements and fixed minimum payments.

“We don’t have the same mortgage system here,” said Christopher Kui, executive director of the nonprofit Asian Americans for Equality (AAFE), which offers support to Chinese and other Asian immigrants. “In China, lenders underwrite a mortgage based on the value of an asset. Income is less important.”

Large parts of New York’s Chinese communities operate as a cash economy, which makes it hard to document the income needed to get a mortgage, sources say.

“[The] down payment is high. But their reported income is low,” said Min Xue, a mortgage banker at the Great Neck-based lending firm Powerhouse Solutions who regularly works with Chinese-American customers.

Xue said many Chinese New Yorkers don’t accurately report their earnings — especially business owners who keep two sets of accounting books. Lack of credit is another issue, he said. “I have to tell a lot of them they need to go get a credit card and come back next year,” the mortgage banker told TRD.

But due to a culture of frugality, help from relatives and expanded loan offerings, homeownership for Chinese immigrants is now more attainable than for most white New Yorkers of a similar pay grade, said Zhou. In many cases, it’s not unheard of for restaurant workers or shop clerks to buy their own homes.

“It may seem contradictory: If you have a low socioeconomic background, how could you own a house?” the sociologist said. “But one of the main components of that ethnic economy is the real estate business.”

Xue said he recently provided a $300,000 mortgage to a Chinese buyer who purchased a $580,000 house in Flushing. The buyer was 26 years old and could afford the home because his relatives gave him $280,000 for the down payment, the mortgage banker said. The debt carries an interest rate of 4.5 percent, according to Xue, which means the buyer is able to live in a single-family home in New York City with $1,520 in monthly mortgage payments.

Up until the 1980s, few Chinese bothered to even apply for loans, Kui of AAFE said. “The banks were not lending to the Asian communities” even though they received plenty of deposits from them, he explained. Then, over the past three decades, several local banks were founded with a focus on issuing mortgages to Chinese immigrants. Today about half a dozen small community banks focus on serving Chinese-Americans in New York.

Up until the 1980s, few Chinese bothered to even apply for loans, Kui of AAFE said. “The banks were not lending to the Asian communities” even though they received plenty of deposits from them, he explained. Then, over the past three decades, several local banks were founded with a focus on issuing mortgages to Chinese immigrants. Today about half a dozen small community banks focus on serving Chinese-Americans in New York.

Following their lead, many big national and international financial firms have also expanded their footprints to New York’s Chinese communities. Lenders including Wells Fargo, JP Morgan Chase and TD Bank now offer Chinese-language services at their branches, while larger Chinese-American institutions, such as East West Bank and Cathay Bank, also have a stake in those neighborhoods. New York’s Chinese-American community banks are small by most standards in the country’s financial industry. First American International Bank — which was founded by Chinese immigrants in Brooklyn in 1999 — had $329 million in residential mortgages and $260 million in commercial mortgages on its books as of June 30, up from $289 million and $144 million, respectively, a year earlier.

Apart from standard residential mortgages, the bank also offers what it calls “portfolio loans.” These mortgages, which are tailored to Chinese immigrants, don’t require tax returns or pay stubs. Instead, the bank requests a letter from an applicant’s employer stating how much money he or she makes. Friends and relatives who chip in for the down payment also need to send letters to the bank vouching for their investment. The minimum down payment is 40 percent, which is high by U.S. standards. But interest rates are far from predatory.

First American’s CEO, Mark Ricca, told TRD that the bank currently charges 4.3 percent on a 30-year mortgage with five years of fixed interest. That’s not much higher than the average 3.67 percent that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac fixed-rate mortgages carry, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association of America.

“People pay; it’s a tremendous thing,” Ricca said. “If you look at our current delinquency rate, right now it’s just under 0.5 percent.”

But in at least one case, unusual lending practices among the Chinese community banks led to conflict with the law. In 2012, the Manhattan district attorney obtained an indictment against Chinatown-based Abacus Federal Savings Bank for mortgage fraud. The prosecutor alleged that the bank intentionally inflated applicants’ incomes on mortgage documents and issued loans to people who couldn’t afford them, based on the fact that income declarations did not match tax returns or pay stubs.

The bank countered that any wrongdoing was the work of a rogue employee, and that its default rate was far below the national average. Abacus won the case and was acquitted of all charges in June 2015. Representatives for the bank did not return calls for comment.

The brokerage business

Much like the mortgage business, the brokerage and listings business in New York’s Chinese neighborhoods often operates under its own rules. While the high-end market for properties valued at $4 million and up is dominated by the same brokerages as in other parts of the city, the landscape drastically changes at the lower price points.

Listings sites like Trulia and StreetEasy play a minor role when it comes to everyday Chinese immigrants finding homes. Instead, the go-to resource is Multiple Listings Service Viewer (MLSV), an online database that covers Greater New York and Philadelphia, mostly in Chinese. (It’s not to be confused with the national Multiple Listings Service.) MLSV lists 1,024 agents for the five boroughs, but the actual number of agents catering to Chinese immigrants is likely several times larger, sources say. With the influx of wealthy foreign buyers, more relatively small brokerages have sprung up in recent years.

Columbus Park in Chinatown

The listings business in Chinese communities is also remarkably antiquated. Sellers and brokers often find buyers and renters by placing ads in one of the four local Chinese-language print newspapers. And brokers advertise properties in New York’s two major Chinese-American listing magazines, Home Reader and Shop Realty. Paper ads posted on lampposts and physical listing boards are also prevalent.

In Flushing alone, there are 187 brokerage firms with at least one licensed broker or salesperson, an analysis of public records shows.

Winzone Realty — one of the largest brokerages catering to Chinese immigrants in New York — has 800 agents, according to its website. But the collection of smaller firms, such as Lin Pan Realty Group and New Golden Age Realty, among others, accounts for the bulk of listings in Chinese. Lydia Li, who has worked as a broker for five years, said her current firm, Win Team Realty, opened in Flushing just a few months ago. “Because there’s so much demand from Chinese buyers, there’s always work for us,” she said in Mandarin.

And while a set brokerage commission of 6 percent is common in New York, those rates are often negotiable in Chinese neighborhoods and are usually set anew for each assignment, according to several sources.

The business is also intensely competitive, insiders told TRD, and much like with New York’s non-Chinese brokers, there is no shortage of self-pitching. One RE/MAX broker, Koren Dafni, advertises herself in a single print ad as: “Number 1 Top Associate; The #1 Agent in Entire NY State; The #16 Agent in Entire USA; The #32 Agent Entire Worldwide; Lifetime Achievement Award; International Hall of Fame; Chairman’s Club Award and The 1st ‘Circle of Legend’.”

In New York’s close-knit Chinese communities, it helps to have local connections, and those who lack them often struggle, said Andy Chen, a Flushing-based broker at Forward NY Real Estate Corp. “We are a community firm,” Chen explained. “Mostly people find out about us from their friends.”

In some cases, word of mouth can extend 7,000 miles. Jennifer Lo, a seasoned broker at New York’s largest residential firm, Douglas Elliman, said buyers from China will contact her six months before a planned trip to New York. Once they arrive, they typically stay for a week to tour listings and will often make an offer before flying back, she said.

“More and more people are getting EB-5 immigration permits,” Lo told TRD. “So they say, ‘Okay, we got approved for next year — let’s look at a house right now.’’”

Tenements to high-rises

The first stop for Chinese immigrants in New York has historically been Manhattan’s Chinatown. Today, the neighborhood is still filled with rent-regulated apartments, many of them owned by so-called family associations — quasi-collectives, grouped by family names, that began buying up buildings in the 1960s and ’70s and have kept them affordable since.

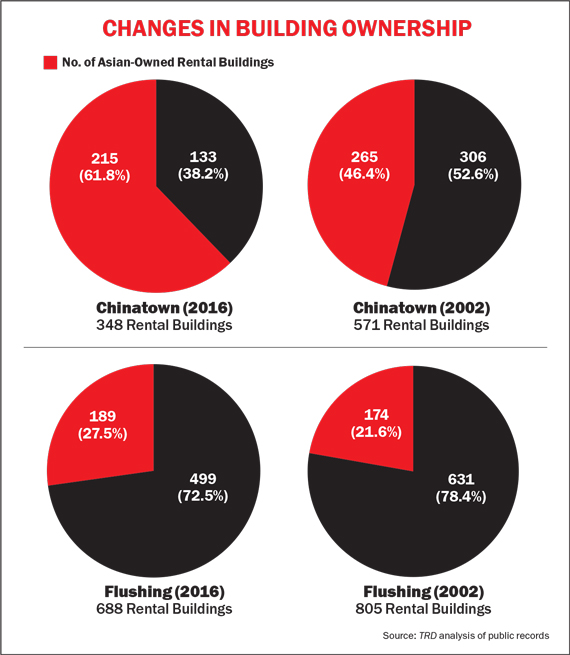

While the number of Asian-owned apartment buildings in Chinatown has declined over the past 14 years, along with the total number of rental apartment buildings in the neighborhood, the percentage of Asian-owned buildings has increased in that time frame. As of September 2016, nearly 62 percent of Chinatown’s 348 rental buildings were Asian-owned, up from about 53 percent of 571 buildings in 2002, a TRD analysis of public records found. In Flushing, nearly 28 percent of the neighborhood’s 688 rental buildings were Asian-owned, up from about 22 percent of 805 buildings in 2002.

While the number of Asian-owned apartment buildings in Chinatown has declined over the past 14 years, along with the total number of rental apartment buildings in the neighborhood, the percentage of Asian-owned buildings has increased in that time frame. As of September 2016, nearly 62 percent of Chinatown’s 348 rental buildings were Asian-owned, up from about 53 percent of 571 buildings in 2002, a TRD analysis of public records found. In Flushing, nearly 28 percent of the neighborhood’s 688 rental buildings were Asian-owned, up from about 22 percent of 805 buildings in 2002.

Instead of a deposit, some landlords in Chinatown ask for so-called “tea money,” in effect an upfront payment for the privilege of renting an apartment. One manicurist who works in Chelsea told TRD she paid $10,000 in tea money for her first Chinatown apartment in 2000.

That tradition, however, has almost completely vanished in the past decade, according to several Chinatown residents. In Flushing, it was never established as a practice.

Chinatown has also been the traditional home of tenements — large, cramped buildings that house mostly male blue-collar workers in bunk beds stacked to the ceilings. One of most talked-about tenements in recent years has been 81 Bowery, which a 2009 Village Voice article described as reeking of “piss and fish paste” even through its closed front door. Although it was intended as a temporary stop, many of its residents ended up staying for years and even decades. In 2013, a CNN report about its dangerous conditions led to the eviction of tenants, but many were able to return after repairs were made.

Now, as a result of heightened real estate activity and more frequent building inspections, these tenements are steadily disappearing from Chinatown. And as more Chinese immigrants enter the neighborhood, where virtually no new housing is being built, many renters turn their attention to the Chinese enclaves of the outer boroughs.

“The modern-day tenement is within single-family homes,” said Kui of AAFE. Landlords in the low-rise residential neighborhoods of Queens and Brooklyn often chop up their homes and rent the lower floors to families or single workers. These illegal basement apartments in homes zoned as single-family have become increasingly prevalent, and they can often lead to sanitation problems, Kui said. It is not uncommon for three to four families to share a home, he added, saying that tenants put up with such cramped conditions because their lives as renters are only meant to be temporary.

For much of New York’s history, the city’s Chinese community was small and concentrated in Chinatown — isolated by racist sentiments and policies in the age of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited all Chinese laborers from immigrating to the States. Following a loosening of those restrictions in 1968, Chinatown’s population exploded. The majority of newcomers were poor, and the neighborhood remained working-class for several decades.

But as space became scarce, Chinatown residents began moving to the Sunset Park area, which was cheap and accessible by subway from Chinatown. In 1988, close to 3,000 Chinese immigrants lived in the neighborhood, according to the Brooklyn Chinese-American Association. By 2013, Brooklyn as a whole was home to 128,000 Chinese immigrants — the vast majority in Sunset Park and Bensonhurst, a New York Times analysis showed that year.

Separately, Taiwanese immigrants began setting up their own community in Flushing in the late 1960s. These immigrants were wealthier than their mainland peers in Chinatown, and Flushing quickly became the more upscale enclave.

The neighborhood’s gentrification was largely the work of one influential developer, Tommy Huang, who built hundreds of properties and turned downtown Flushing into a major shopping destination, according to various reports.

Today, New York’s Chinese community and the real estate market serving it remain heavily concentrated in those neighborhoods of Lower Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens. But as wealthy Chinese continue to flock to the city, that dynamic is in a state of flux, and once-stark boundaries are becoming less clear-cut.

Changing tides

Like many other New Yorkers, low- and middle-income Chinese immigrants are grappling with the rapid pace of gentrification. Kui of AAFE said that landing a mortgage is no longer the biggest challenge Chinese immigrants face in New York’s real estate market. “The big challenge now is housing prices,” he said.

Although parts of Chinatown have remained relatively affordable — largely due to the prevalence of stabilized and public housing and the sway of the family associations — a noticeable change is now underway.

At 83 and 85 Bowery, for example, rent-stabilized tenants have been protesting against landlord Joseph Betesh, who they allege is trying to bully them out to deregulate the two buildings. That is unrelated to the tenement at 81 Bowery.

The neighborhood is gentrifying, said Keith Woo, a broker at Town Residential who grew up in Chinatown in the 1970s. “But it’s slower, and I think it’s because a lot of the housing stock is still owned by old-school landlords,” he said. “There’s quite a few landlords that either don’t want to bother or are happy with what they collect.” Still, Woo, whose parents moved to the States when he was two years old, said he has no doubt that rent-controlled apartments in Chinatown are “on the way out.”

Amid a condo conversion craze, the number of rental units in core Chinatown dropped to 6,605 units by 2016 — down from 16,722 in 2002, according to TRD’s analysis of property records. In Flushing, the number of rental units fell to 23,168 from 27,079 in 2002.

The fact that the newer waves of Chinese immigrants are all the wealthier has accelerated the pace of gentrification in those communities. And with the rollout of the new 10-year visa program between China and the U.S., it’s all the more appealing for wealthy Chinese immigrants to invest in New York property. Many of the latest development projects in Flushing are pricey condos.

Yu, the health-care employee, for one, said he decided to buy a condo on Staten Island because he couldn’t afford to buy in Bensonhurst, where he was living before.

For many years, Chinese immigrants who moved to New York would take entry-level jobs, rent apartments in Chinatown and gradually work their way up while securing a green card or citizenship. After doing so, many would purchase homes in Flushing or on Long Island and move their families out. But now there’s another trend, which started about a decade ago, Lo of Elliman explained.

“Young Chinese nationals are coming here for college, and when their parents come to visit, they help their kids buy an apartment in Manhattan for $1 million or so,” she said.

One member of New York’s new wave of Chinese immigrants is 26-year-old broker Chou, of NY Best Homes Realty, who moved to Vermont as a teenager in 2006. After graduating from New York University five years ago, he bought a two-bedroom condo in Brooklyn’s posh Dumbo neighborhood and paid all cash with the help of his parents.

“Sometimes it’s difficult to explain why the Chinese love buying homes,” Chou said. “It’s just the culture.”

But, in addition to economic shifts, cultural changes are also likely to transform the real estate market for Chinese immigrants, according to sources. The children of Chinese immigrants are generally much more similar to Americans of other ethnic backgrounds than their parents. And wealthy newcomers are often educated at U.S. colleges and far better at English than poorer immigrants of generations past. In turn, they may be more likely to go to a firm like Douglas Elliman to buy a home, and to get a mortgage, if they even need one, from a major national bank. They certainly won’t need to move into a tenement.

Wealthy Chinese immigrants are increasingly working with major brokerages in the city that hadn’t previously catered to Chinese clients, according to Lo.

“Even a year and a half ago, brokers had no idea how to accommodate the buyers from China,” she said. “Now, all these firms in Long Island — they know everything. It’s because they know the Chinese market won’t stop.”