UPDATED, March 2, 5:17 p.m.: It was the spring of 2015, and New York City developers were madly rushing to get their residential projects approved before the popular 421a tax abatement program expired. But in the midst of the frenzy, the city’s development world hit an unexpected snag: A government employee went on vacation.

While that might seem like the punch line of a joke, for developers with millions of dollars of tax breaks on the line it was anything but funny. The employee, a senior examiner at the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, was a key stop on the road to green-lighting construction projects within 200 feet of a subway tunnel. With that one official away, the MTA was suddenly swamped with a flood of applications it couldn’t keep up with.

“No one could get their approval,” said one developer, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of antagonizing an agency he depends on.

The developer, who called the MTA “terribly inefficient,” said his Brooklyn rental project was saved when the state extended the sunset date of the 421a program.

While that 11th-hour reprieve may have spared a lot of projects from being scrapped, the episode underscores what developers, contractors, tenants, architects and attorneys have long bemoaned: that the public agencies tasked with overseeing NYC’s multibillion-dollar real estate and construction industries often struggle to enforce their own rules and to keep pace with the requests they receive.

With that in mind, The Real Deal spoke to about 30 real estate professionals, housing advocates and government officials about the inner workings of four key city and state bodies — the city Department of Buildings, the state Attorney General’s office, the city Department of Finance and the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal.

What emerged was a depiction of offices often swimming in a sea of red tape. Not only are they understaffed, underfunded and overworked, they are also reliant on antiquated systems.

While the New York real estate world — at least on the high end — is creating 3D renderings, launching tech apps and building supertall skyscrapers, most of these agencies are stuck in the 20th century, relying on paper filing and time-consuming in-person inspections.

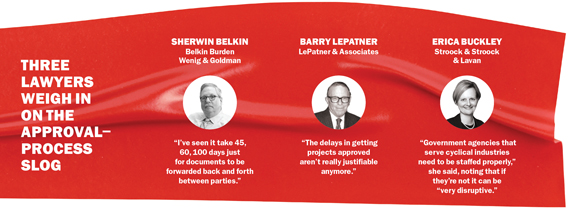

“The delays in getting projects approved aren’t really justifiable anymore,” said Manhattan-based attorney Barry LePatner, who specializes in real estate and construction.

“The delays in getting projects approved aren’t really justifiable anymore,” said Manhattan-based attorney Barry LePatner, who specializes in real estate and construction.

When a project is delayed by more than a year “for no just reason,” it costs the public in the form of lost tax revenue, housing stock and jobs, he argued.

The situation isn’t all bleak.

Several agencies are pushing to reform, beefing up staff and launching online programs to accelerate operations. But they are up against layers of bureaucracy set in place decades ago.

In addition, some of these offices are in better shape than others. Attorney General Eric Schneiderman’s office, for example, is considered relatively efficient.

But the government offices that deal with development and housing still by and large remain encumbered by outdated protocols and systems, multiple sources confirmed.

The impact of these issues is not just being seen on developers’ expense ledgers. In some cases, the problems have led to lax enforcement that’s played a role in construction deaths and safety hazards at New York City properties. In other instances, it has led to the illegal deregulation of thousands of rent-stabilized apartments.

Sources note that these agencies have the added challenge of working with an industry that is very much tied to market cycles. While government offices tasked with enforcing food safety and sanitation, for instance, have a relatively steady annual workload, the same is not true for real estate.

During the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, hundreds of projects in the city ground to a halt. Then, between 2010 and 2015, construction permits ballooned 749 percent, according to data from the New York Building Congress, one of NYC’s largest construction industry trade groups.

But hiring staff to deal with a skyrocketing workload is not easy.

While agencies like the DOB and the AG’s office have beefed up their headcounts, it takes time to bring on new people.

Erica Buckley, an attorney at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan who until last year headed the AG’s Real Estate Finance Bureau, said that office has been dealing with shortages of administrative staff, in part because union rules draw out the hiring process.

From left: Mayor Bill de Basio, DOB Commissioner Rick Chandler, Department of Health & Mental Hygiene Commissioner Dr. Mary Bassett and Council Member Vanessa Gibson at a City Hall press conference, where the mayor signed a new law involving cooling-tower inspections.

Still, she added that the AG’s office has hired attorneys (who aren’t usually subject to union rules) to cope with the additional workload.

“Government agencies that serve cyclical industries need to be staffed properly,” she said. Not having enough employees “can be very disruptive.”

The Department of Buildings

Mayor Bill de Blasio was ready to leave for a family vacation in Italy after a busy first six months in office in July 2014. But first he needed to appoint a new DOB commissioner — a post that remained vacant long after he named all other agency heads and deputy mayors.

De Blasio had reportedly offered the job to several people, who all declined. A few days before he left, the mayor finally found a taker in Rick Chandler, a Hunter College executive and former veteran DOB employee.

On July 21, 2014, Chandler, an engineer by trade, took over one of the Big Apple’s least popular and most problem-ridden agencies, not to mention one with an impossibly broad task: overseeing every single building and construction site in the five boroughs.

But the DOB is still falling short in the eyes of many.

Last year, a “Red Tape Commission” convened by New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer surveyed small-business owners, who gave DOB “the lowest satisfaction rating of any city agency.”

Then, in September, the DOB was needled in the press for failing to maintain its own Lower Manhattan building, where, according to the New York Post, a falling piece of concrete forced the closure of a parking garage.

“Yes, we get the irony,” DOB spokesman Alexander Schnell told the paper. “But in many ways DOB is just like any other tenant in the city. We have no construction crews of our own, so we need our landlord to repair the building.”

The department’s struggle to regulate safety conditions citywide goes back decades.

In 2000, the DOB even came close to being shuttered by then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, who wanted to merge it with the Fire Department after five DOB employees were indicted for taking bribes to speed up approvals.

Giuliani’s successor, Michael Bloomberg, however, reversed course and instead focused on reforming the agency, most notably by simplifying the building code.

Despite the attempts to streamline operations, the DOB remains a favorite industry punching bag.

“They run like their own shadow government,” said Donna Olshan [TRDataCustom] of the residential brokerage Olshan Realty, who publishes a weekly report on contract activity in the luxury market, which includes new developments.

“The DOB is a big maze, but on the other hand they do come up with a lot of [important] regulations,” she added. “The point of it is to protect the public.”

Among developers, architects and lawyers, the most common complaint about the DOB is that filing permits is too complicated and time-consuming.

“I probably sign 100 pieces of paper a week for the DOB, which is crazy,” one developer said. “We should do all of this stuff online.”

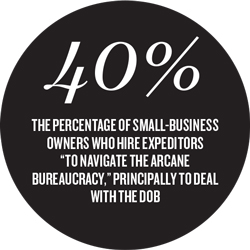

The existence of expeditors — professionals (often former DOB staffers) hired to help developers navigate the DOB and other agencies — speaks to just how much red tape there is to cut through.

The existence of expeditors — professionals (often former DOB staffers) hired to help developers navigate the DOB and other agencies — speaks to just how much red tape there is to cut through.

According to Stringer’s Red Tape Commission, 40 percent of small-business owners hire these so-called fixers “to navigate the arcane bureaucracy,” principally to deal with the DOB.

But another big reform push is underway.

In February 2015, de Blasio announced a plan to invest $120 million over four years to hire 320 DOB employees “to enhance public and worker safety, slash wait times and delays and modernize all aspects of the agency to meet the needs of a 21st-century city.”

“We knew we needed to address these issues,” Chandler told TRD in January.

In addition to hiring, the agency has been gradually rolling out DOB Now — a $29.6 million computer system that launched in August and is designed to replace paper filing. So far, users can file permits for sprinkler, plumbing and facade work as well as standpipes online.

The city’s goal is to digitize all DOB filings, but Archana Jayaram, the agency’s deputy commissioner of strategic planning and policy, said it’s a complex task that will take a couple of years to fully implement.

But even with the partial implementation, DOB Now, she said, allows the agency to quickly identify backlogs and address them by shuffling around staff and resources.

There have been some recent tangible improvements.

Between fiscal years 2015 and 2016, the time it took to complete first reviews for new buildings — which take place when a complete set of documents is filed — was cut down by 3.8 days in the DOB’s borough offices and eight days at its Lower Manhattan center, according to City Hall’s most recent mayor’s management report.

But despite that, the agency fell behind in addressing complaints. And some say the DOB is not doing enough to crack down on developers.

While the agency completed 148,162 construction inspections in fiscal year 2016 — up about 5 percent from in 2012 — construction-related injuries rose a massive 235 percent, to 526 from 157, according to the report.

Michael McKee, of the advocacy group TenantsPAC, called the DOB “probably the worst” agency when it comes to protecting tenants.

The agency, he said, regularly rubber-stamps demolition permits for buildings that developers claim are empty, without even checking with other agencies to determine whether any rent-stabilized tenants are living in them.

“The de Blasio people keep talking about how they’re going to make reforms, but they’ve been talking about this for three years,” he said.

A DOB spokesperson told TRD that the agency has hired 140 new inspectors and increased fines for unsafe construction sites, among other measures.

Marc Weissbach, CEO of the architecture, construction and engineering consultancy Vidaris, was more tempered than McKee, arguing that the DOB “is trying to do a lot of good things.”

The problem, he said, is less with DOB and more with the independent DOB-accredited building inspectors. He said the “huge majority” of routine building inspections are performed by these players.

In 2015, a two-year old girl was killed while sitting on a bench with her grandmother outside a senior housing facility at 305 West End Avenue — owned by Esplanade Venture Partnership and Alexander Scharf — when part of a windowsill fell off and hit her. An investigation found that the engineer hired to inspect the building deemed it safe without ever actually inspecting it.

The DOB strengthened its own procedures for façade enforcement in the wake of that death.

The Attorney General

In the first eight months of 2015 and 2016, NYC developers filed a combined 375 applications for condo offering plans.

While the flood of new supply was a boon for condo buyers, for the AG’s Real Estate Finance Bureau, which is tasked with dealing with those plans, it was a major headache.

Under the Martin Act, sales of co-ops and condos in New York State are treated as securities, and offering plans need to be cleared by the AG’s office.

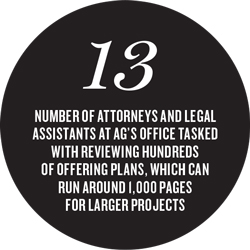

But the Finance Bureau, which is now headed by former HPD official Brent Meltzer, is small. According to the AG’s website, as of January, there were 13 attorneys and legal assistants tasked with reviewing these offering plans, which can run around 1,000 pages for larger projects.

And it uses an antiquated cataloging system in which staffers write project information on index cards and stow them away in giant filing cabinets, according to a 2014 story in the New York Times, which also noted that the office has to ship about 100 boxes a week upstate to free up room for paperwork.

Almost inevitably, the workload leads to oversights, said Robert Dankner, who heads the residential brokerage Prime Manhattan Realty.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman

In addition, some said the office could be doing more to protect buyers. Dankner said he recently had a client who purchased a condo in a new development, but the developer sent over an offering-plan amendment approved by the AG just before the unit closed. Buried in that amendment was the fact that several of the unit’s windows, which were advertised as “facing a park,” were now categorized as “lot facing,” meaning they could be permanently boarded up by the developer in the event of construction next door.

The AG’s office “didn’t feel it was material when in fact it was,” Dankner said, arguing that the amendment should have been rejected. Dankner declined to name the building and the buyer, citing client confidentiality.

An AG-reviewed offering plan is meant to ensure that buyers get the units they signed up for. But determining what constitutes a “material change” remains a gray area.

An approved offering plan for the condo development at 565 Broome Street reviewed by TRD, for example, states that a 5 percent change in the unit’s floor size is not material. Neither are concrete cracks “that do not impair the structural soundness of the building,” scratched surfaces or warped doors.

Sales at the building — which is being developed by Bizzi & Partners, Aronov Development and Halpern Real Estate Ventures — launched in July.

In reviewing these plans, the AG’s office has to strike a balance between protecting buyers and ensuring that developers aren’t overburdened. While no buyer wants a damaged unit, few developers will build a condo if a minor scratch on a kitchen counter is grounds for a deposit return.

Olshan said she thinks the AG’s office has been shifting the balance too far in favor of developers. If they are allowed to include language “that absolves them of almost anything,” she said, “what’s the point of the AG’s office?”

A source in the AG’s office said the significance of a 5 percent size reduction varies — if it’s all concentrated in a small kitchen it could have a big impact, but if it is spread out over a large luxury apartment it may not even be noticeable.

Buckley, the former Finance Bureau head, contended that the offering plan is “just a guide for the purchaser. They still have to do their own due diligence.”

Some brokers and attorneys also criticized the AG’s office for not holding developers’ feet to the fire on reporting sales. The office doesn’t require updates on the number of contract signings at new projects — a reality that has made it easier for brokers and developers to inflate their contract signings, making their buildings look more popular than they actually are, as TRD reported in October.

Those criticisms aside, industry observers credit Schneiderman, who took office in 2011, with significantly improving the regulation of condo and co-op sales. The office has begun strictly enforcing a 30-day time limit to respond to submissions and has tried to give developers clearer guidance on required paperwork.

Sources say Schneiderman has also beefed up real estate prosecutions, though statistics on how many developers he has gone after were not immediately available.

Last year, however, the AG’s office reached a high-profile settlement with developer Shaya Boymelgreen over alleged defects at his buildings that will bar him from selling condos for two years. And in 2015 it won a $1.2 million settlement from Newcastle Realty Services after the firm allegedly reached illegal buyout deals with tenants.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo

“I am proud of the work our Real Estate Finance Bureau does to preserve and restore affordable housing, crack down on tenant harassment and hold some of New York City’s biggest developers accountable,” Schneiderman told TRD in a statement.

He added: “The New York housing market is full of unique and varied challenges, and we will continue to find innovative solutions that safeguard the rights of tenants and purchasers.”

The next big step for the AG will be to transfer much of the outdated offering-plan process from paper filing to online submissions. According to sources, work on an online system is underway. Another priority is more hiring. Those who have dealt with the bureau say the flood of condo filings has put a strain on it.

“In hot markets, they’re overworked,” said a lawyer who asked not to be named because of regular dealings with the bureau. “There’s too much on their plate.”

The NYC Department of Finance

At the beginning of each year, the city’s Department of Finance assesses every New York City property’s value to determine its tax bill.

For Vornado Realty Trust and the Trump Organization, 2016 was more interesting than usual.

The department hiked the tax assessment of their jointly owned office tower at 1290 Sixth Avenue by a staggering $137.5 million. After a complaint and a lengthy review by the Tax Commission — the independent body tasked with reviewing tax assessments — the number was slashed by $92.3 million, making it the single largest assessment reduction of the year.

Citywide, 16 buildings had initial assessments that were at least $20 million higher than their revised assessments, according to the Post.

To critics, these massive revisions highlight the department’s inability to nail accurate property values — and speak to the bureaucracy’s failure to do its job.

Arnold Mazel, an attorney at the Manhattan-based law firm Goldberg Weprin Finkel Goldstein, blamed the inaccurate assessments on two design flaws: an inherent bias toward jacking up assessments so that the city can haul in more revenue, and the use of outdated information. (The department bases its assessments on income from the previous year, so if an anchor tenant, say, suddenly departs, the lower rent roll is not captured.)

“A lot of the time, the Department of Finance has an idea of where they want the assessment to go, it’s a subject of determination,” Mazel, who represents building owners, argued.

Timothy Sheares, the department’s deputy commissioner, rejected that characterization.

“That’s just not the case. Our job is to value correctly,” he said. “If the tax rate was 1 percent or 100 percent, my valuation was the same.”

He also said that a building sitting vacant in a hot market may be more a function of bad management than of low value. “If the property is 100 percent vacant, that doesn’t mean the property doesn’t have value,” he said.

He also said that a building sitting vacant in a hot market may be more a function of bad management than of low value. “If the property is 100 percent vacant, that doesn’t mean the property doesn’t have value,” he said.

The agency, he added, launched an internal review a year ago to look at inefficiencies. In recent years, it’s also upped its game by introducing interactive tax maps online and is sharing more information with building owners on how their taxes are collected.

And this month, the department will start sending photographers to properties across the city to help measure buildings and spare its inspectors field trips. It is also working on a rollout of 3D tax maps, he said.

The Tax Commission holds hearings on thousands of assessment appeals annually.

“Within five, six months they listen to 53,000 petitions. That’s a lot of action,” said Harry Dublinsky of accounting and consulting firm EisnerAmper.

Hearings usually last only a few minutes, Mazel said, and a decision is reached. “They’re actually a pretty effective agency,” he said.

The Division of Housing and Community Renewal

New York City has about 1.3 million rent-stabilized apartments, and it’s the little-known Division of Housing and Community Renewal — or DHCR — that’s tasked with overseeing them.

According to industry and tenant advocates, the DHCR, which as of mid-2015 reportedly only had 25 staffers, is not doing a great job. But the complaints about what’s going wrong vary.

Sherwin Belkin, a landlord attorney with Belkin Burden Wenig & Goldman, said it takes far too long — three to five years is not uncommon — for the agency to approve demolitions of buildings that house regulated tenants so that a developer can build a replacement.

Although he acknowledged that tenants’ rights need to be carefully reviewed, Belkin argued that it shouldn’t take that long. The long lag time, he noted, costs developers steeply in interest payments and revenue.

“I’ve seen it take 45, 60,100 days just for documents to be forwarded back and forth between parties” through the DHCR, he said. “The process lends itself to delay, the agency’s understaffing exacerbates that delay, and anti-owner predilections add to that.”

Tenant advocates, naturally, have a very different perspective.

“Taking a long time to displace people from their homes is not a bad idea,” said David Hershey-Webb, an attorney at the Lower Manhattan-based firm Himmelstein, McConnell, Gribben, Donoghue & Joseph who represents tenants in DHCR disputes.

The problem, he argued, is that the DHCR is “not doing a good job of policing the landlords illegally taking apartments out of stabilization.”

Hershey-Webb said another big problem is that it often takes years for the department to rule on tenants’ complaints connected to rent overcharges. And the penalty of simply having to pay back those overcharges is not enough of a deterrent to landlords, he said. (The DHCR can, however, charge landlords triple damages for “willful rent overcharge,” according to its website).

In 2009, tenants at Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village on Manhattan’s East Side thought they had won a major victory when the Appellate Division of State Supreme Court ruled that then-landlord Tishman Speyer had illegally overcharged them while accepting the J-51 tax abatement. The Manhattan court ruled that landlords who receive the abatement must keep leases stabilized.

But the DHCR — along with the city’s Department of Finance and Department of Housing Preservation and Development — never enforced the ruling.

In 2015, ProPublica revealed that landlords accepting J-51 breaks charged market rents for 50,000 units when they shouldn’t have. In that wake of that revelation, Gov. Andrew Cuomo mandated that the units be restabilized. But it was later revealed that the state didn’t notify tenants and did not force landlords to pay back overcharges or return units to prior rent levels.

“The basic problem we have is that the rent-regulation system is complaint-driven,” TenantsPAC’s McKee said. “If a tenant does not file a complaint, nothing happens.”

In 2012, Cuomo launched the Tenant Protection Unit, a DHCR division tasked with proactively enforcing rent rules and going after nonabiding landlords. The unit claims to have returned 8,963 units to stabilized status in 2016.

But advocates are not happy.

“Cuomo’s great new project [the enforcement unit],” McKee said, “basically amounts to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.”

City vs. State

While the agencies overseeing the real estate industry are showing signs of improvement, inefficiencies still abound.

According to the Real Estate Board of New York — the industry’s main trade organization — the industry generated $116.1 billion in economic activity in 2015 and accounted for 41 percent of the city’s tax revenue.

So it could be argued that even super-modern government agencies would struggle to police an industry of such vast size.

But some say one big problem is that the agencies overseeing the industry are split between the city and state.

“The biggest thing to solve is the city-state conflict.” said the Regional Plan Association’s Moses Gates.

“You’re dealing with regular New Yorkers with regular problems who have just zero idea which of these alphabet-soup agencies to go to,” he said. “If you see a pothole, you know you call the Department of Transportation, whereas with housing problems it’s a lot tougher.”

LePatner argued that city agencies are “in the second inning of a nine-inning game” in terms of adopting necessary new technologies, adding that there has not been enough of an effort to invest in upgrades.

“The return on investment will dwarf whatever the cost is,” he said.

But, LePatner said, the onus doesn’t just fall on government. The industry should also push for quicker adoption of new technologies, he said, though he noted that real estate’s own procedures are often antiquated.

“Everyone in the business shrugs their shoulders and says, ‘But we’ve been doing this for so many years, why should we change?’,” LePatner said “It’s built into the industry.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story mistakenly implied that real estate attorney Sherwin Belkin thinks processing a demolition request in two years is an acceptable time frame. He said the process takes too long. The story has been updated accordingly.