Two Herald Square is waiting for its white knight, but some are wondering whether its most likely savior is having second thoughts about a rescue.

The 11-story building — which sits on Broadway between 34th and 35th streets — is teetering on the brink of foreclosure.

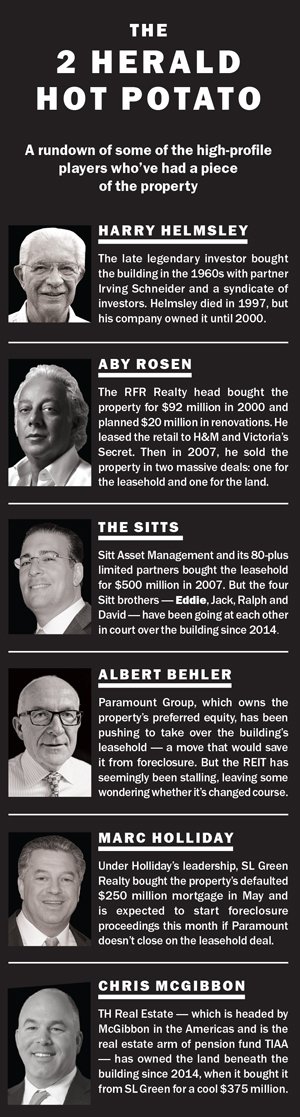

In July, a New York State Supreme Court judge gave the Paramount Group, which owns the preferred equity in the building, the green light to close on its planned bid to take control of the pricey leasehold on the property.

But the real estate investment trust, which is led by CEO Albert Behler, has yet to make a move. And every day that goes by brings more fear for Sitt Asset Management, which owns the leasehold.

If Paramount doesn’t close the deal by sometime in October, another real estate giant — SL Green Realty, which bought the building’s defaulted $250 million mortgage in May — is expected to start foreclosure proceedings. If that happens, 2 Herald Square will become one of the few prime Manhattan office buildings to meet that fate — despite the slowing market that’s putting more pressure on property owners.

For the building itself, this potentially dire situation is just the latest chapter in a long history of highs and lows. The property has had a string of high-profile owners, including Harry Helmsley and Aby Rosen, and seen periods of both neglect and aggressive investment. Not helping matters is that the four brothers who founded Sitt Asset Management have long been at each other’s throats in court.

But despite the building’s messy and complicated ownership structure, its location is prime and it has several marquee tenants, including office-sharing giant WeWork and Victoria’s Secret. Yet it’s still had 59,000 square feet of prime retail sitting empty for over a year and a half.

And as retail vacancies plague the market and Manhattan’s investment sales sector feels the squeeze — sales volume was down 55 percent in the first half of this year, according to Real Capital Analytics — questions are looming about the fate of 2 Herald Square. There’s also the question of whether it should even be considered a bellwether for the market if it falls into further distress.

For now, however, the clock is ticking on the foreclosure.

“With every day, roughly $80,000 of interest accrues to SL Green,” said Stephen Meister, who represents Ralph Sitt, one of the four bickering brothers.

The lost deals

The last four months have been a whirlwind of activity for 2 Herald Square, which is located at 1328 Broadway.

In mid-May, news broke that Morris Bailey’s JEMB Realty was looking to pony up $350 million to close on the building’s leasehold.

It seemed too good to be true — a deal that would rescue the office-and-retail property and prevent Sitt Asset (along with its 80-plus investors) from losing its shirt on the investment.

But that bid from JEMB — along with one from Jamestown Properties and another from Alpha Equity Group, which was seeking cash from private equity firm Savanna that it ultimately couldn’t lock in — fell by the wayside.

Instead, Paramount, which had a negotiating advantage because of its preferred equity in the building, stepped in.

While Paramount declined to comment, if it does pull the trigger on the purchase it’s likely to be for “big money,” according to Meister.

Once Paramount pays for everything — from the millions in defaulted interest to the renovations promised to several office tenants — the bill is likely to clock in north of $300 million, Meister said. And if it even happens, the Paramount deal would be a takeover rather than an outright sale.

With SL Green now looming over the property, the possibility of a straight leasehold sale to an outside company like JEMB or Jamestown is seeming more like a fantasy, sources say.

A syndication operation

Packed into this 354,000-square-foot building is a lot of New York City history.

Built in the early 1900s as an office building and known as the Marbridge Building, the property had the once-bustling but long-defunct men’s clothing store Rogers Peet at the base.

It also has a history of being owned by well-known players who’ve relied on syndicates of investors to bankroll their purchases. Those owners include Sam Kronsky in the 1920s, Henry Goelet and Morris Furman in the 1950s and Harry Helmsley in the late 1960s.

Helmsley, who is often credited with popularizing syndicated purchases of New York City trophy buildings, owned it for decades with Irving Schneider and a syndicate of limited partners.

Helmsley died in 1997, but his company owned the property until 2000, when Aby Rosen’s RFR Realty scooped it up for $92 million.

Shortly after the purchase, Rosen described the building’s small commercial spaces as “glorified sweatshops.”

“When we bought this building, it was quite a disaster,” Rosen told the New York Times. “They basically did not spend any money on the building. The tenants were small shoe companies, small apparel people who took the space as is. Some of them have no air conditioning.”

Rosen planned $20 million in renovations and signed Swedish apparel company H&M to 66,000 square feet, including part of the ground-floor space with prime Herald Square frontage. Victoria’s Secret soon leased part of the retail space, and French advertising giant Publicis and Mercy College became the primary office tenants.

Mortgage documents filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission in 2003 show that the building’s appraised value was $200 million.

In 2007, with those long-term tenants in place and the retail market booming, RFR sold the building in two massive, separate deals: one for the leasehold and one for the land.

Sitt Asset Management — led by brothers David, Eddie, Ralph and Jack Sitt and their mother — bought the 70-year leasehold for a whopping $500 million. SEC records show that the company invested $275 million in cash equity. The Sitts were under the gun to make a purchase at the time because they were executing a 1031 tax exchange — which allows sellers to defer capital gains if they buy another property. (The year before, they had sold 6 Times Square for $300 million.)

At the same time, SL Green and Gramercy Capital Corp., a REIT now known as Gramercy Property Trust, paid $225 million for the land.

The two deals spoke to the rapid appreciation of not only the building but also the commercial market. They also gave RFR a hefty payday.

RFR executive Jason Brown told the New York Post at the time that “the stars were all aligned for the building to be traded.”

“A good portion of that 2007 transaction was driven by expectations on the retail sector,” RCA’s Senior Vice President Jim Costello said. “People were so enamored with retail. But then the downturn happens, consumers pull back everywhere, and retail just is not valued as highly by investors as it had been in the housing boom.”

By 2014, SL Green wanted out and sold the land to TIAA-CREF — the retiree financial services giant, which is now called TH Real Estate — for $365 million, turning a tidy profit. The deal gave the Sitts the option to buy the land from TIAA in 2027.

But two years later, in 2016, the building hit a snag.

H&M and Publicis moved out, leaving more than 180,000 square feet of retail and office empty. To rub salt into the wound, H&M moved to a new megastore nearby on 34th Street at Vornado Realty Trust’s 435 Seventh Avenue. Publicis, meanwhile, consolidated its space at Rudin Management’s 1675 Broadway, where it has 580,000 square feet.

Avison Young has been marketing the 59,000 square feet of vacant retail, including 12,500 square feet on the ground floor, since June to no avail, sources said. And Cushman & Wakefield was marketing it before that.

CBRE’s Richard Hodos, who represented Victoria’s Secret in its leases at the building, said the tumult at 2 Herald is not indicative of softness in the surrounding Herald Square retail submarket.

“While this asset’s situation is a bit unique, this intersection is still a very valid retail destination in New York City, and it will remain so as long as Macy’s maintains its flagship presence there,” Hodos said.

Self-inflicted wounds

Since November 2014, the Sitt family has been tangled in an ugly and head-spinning family court battle.

In multiple suits that seem ripped from a spy novel, Eddie has claimed that Ralph’s mismanagement of the property has run the building’s finances into the ground.

He’s accused Ralph and David of trying to dilute his and Jack’s stakes in the building in an attempt to squeeze them out. He also accused Ralph of “starving the property” and claimed that Ralph forged an operating agreement to make it seem as if he were the property ownership entity’s sole managing member — and then used that to secretly negotiate buyouts with investors.

In March of this year, a group of investors made that same claim against Ralph, noting that the alleged fake document allowed him to secure the $30 million in preferred equity from Paramount without the investors’ consent.

Meister has disputed the claims, saying Ralph has been the sole managing member for a decade. The lawsuits have been merged into one case, which is ongoing.

The litigation has made the family’s attempts to stabilize the building virtually impossible.

Court documents showed that back in November 2016, the property was losing $1.7 million a month.

CBRE’s Shawn Rosenthal — whom Ralph hired late last year to lock in a $300 million loan — wrote to the court, noting that several lenders declined the opportunity to issue a loan on the property. Morgan Stanley passed “primarily because of the litigation issues between the partners,” Rosenthal wrote.

When SL Green later bought the existing loan, it was already in default. Despite the internal drama, the owners did strike a deal in late 2016 with WeWork for 122,000 square feet, filling the office vacancy left by Publicis. WeWork, which took the address of 950 Sixth Avenue on the eastern side of the building, declined to comment.

And the interest in the leasehold from established players like Jamestown and JEMB suggests that investors still see a financial upshot. Amid the market slowdown, the $350 million JEMB deal would have been one of the biggest investment sales trades of 2017.

Still, RCA’s Costello said that the property is likely also feeling the effects of the hit that midmarket retailers are seeing. Even if the building had sold two years ago, when the market was booming, it might not have achieved the record-setting prices that other retail properties were seeing, he said.

“The retail that was booming at the time serviced the high end of the market, brands like Hermès and Louis Vuitton, whereas this asset was bought in 2007 with tenants aimed at the middle market, H&M and Victoria’s Secret,” he said. “The fact that the middle of the market for consumers is now facing challenges likely hurt this asset.”

The motley investor crew

If 2 Herald Square does fall into foreclosure, it would not be the only historic Midtown office building to do so in the past year.

In March, Brookfield Property Partners, in its capacity as a lender, foreclosed on the Brill Building at 1619 Broadway. And Wells Fargo is currently foreclosing on the Lever House at 390 Park Avenue after RFR defaulted on the CMBS mortgage.

Like those two buildings, 2 Herald Square has its own special predicament.

The property is unique in that the leasehold has a heavily syndicated ownership structure. Some of the notable investors include the Aini family, which frequently partners with investor Isaac Chetrit, and Solly Assa, who allowed his tenants to run apartments as illegal hotels through Airbnb, according to a recent court ruling. (The Ainis declined to comment, and Assa could not be reached).

The Sitts, who declined to comment, have a 51.75 percent interest in the leasehold. Paramount’s $30 million in preferred equity investment, meanwhile, has now dwindled down to 4.8 percent, according to a quarterly earnings report from the REIT in June.

Although Paramount’s current exposure is relatively small, it would lose its remaining investment if SL Green forecloses.

According to sources, Assa and Ralph Sitt had an agreement stipulating that two-thirds of the leasehold’s 80-plus limited partners must sign off on a sale or restructuring. Ralph, who now runs his own investment firm, Status Capital, is “within a whisper” of collecting those required consents, Meister said. But sources familiar with the building said there are other conditions that need to be met to allow a sale.

If SL Green, which declined to comment, forecloses, it would either hold an auction and sell the leasehold to the highest bidder or take control of the property, an option sources say the REIT hasn’t ruled out.

When it bought the debt in May, SL Green was clearly looking to make a profit and betting that the leasehold’s new owner — Paramount or another firm — would pay off the loan. And if the Paramount deal goes through, the investors will obviously be better off than if there’s a foreclosure. They won’t, however, make out as well as they would have if an outside investor had snapped up the property.

“There is an enormous built-in gain [in doing the deal],” Meister said. “There is a huge drawback to not doing the deal. To move forward with foreclosure will be a disaster for the building’s investors.”