Last year, there were no winners — just brokerages that suffered less than the rest.

The coronavirus pandemic crippled New York City’s residential real estate market in 2020. Agents were banned from showing homes for nearly an entire quarter, and many wealthy Manhattanites fled the city, wounding an already fragile luxury market. That only made brokerage margins thinner, driving a surge in the M&A activity that has been a hallmark of the sector in recent years.

The coronavirus pandemic crippled New York City’s residential real estate market in 2020. Agents were banned from showing homes for nearly an entire quarter, and many wealthy Manhattanites fled the city, wounding an already fragile luxury market. That only made brokerage margins thinner, driving a surge in the M&A activity that has been a hallmark of the sector in recent years.

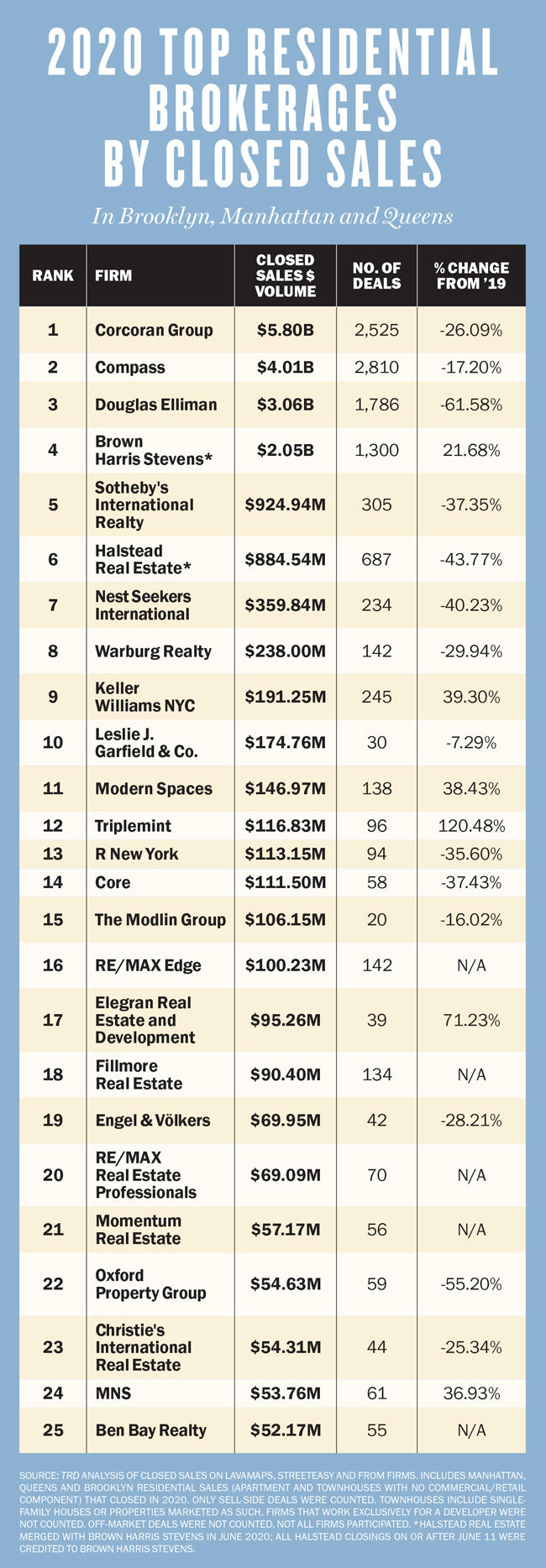

The Real Deal’s annual brokerage ranking, which tracks the number of sell-side deals that closed in 2020, reflects these times. Most firms saw volume fall.

“Obviously there’s a decline,” said Pam Liebman, CEO of the Corcoran Group. Still, she said she believed her agents “outperformed the market.”

She was right.

Corcoran took the No. 1 spot on the sales ranking, with $5.8 billion in closed sales in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens. Though sales fell 26 percent from 2019, the brokerage was able to beat out its two biggest rivals.

Compass, which is on the verge of going public, claimed the No. 2 spot with $4.01 billion in sales, a 17 percent year-over-year drop. And Douglas Elliman fell from the top of the previous ranking to No. 3 with $3.06 billion in 2020 sales — a nearly 62 percent plunge from the year prior.

Together, the top 25 firms reported $18.92 billion in New York City closed sales last year, down 32 percent from $28 billion in 2019. TRD pulled listings from real estate data firm LavaMap and cross-referenced these listings with closed deals in public records and with the brokerages. Sales handled in-house by developers and off-market transactions were excluded.

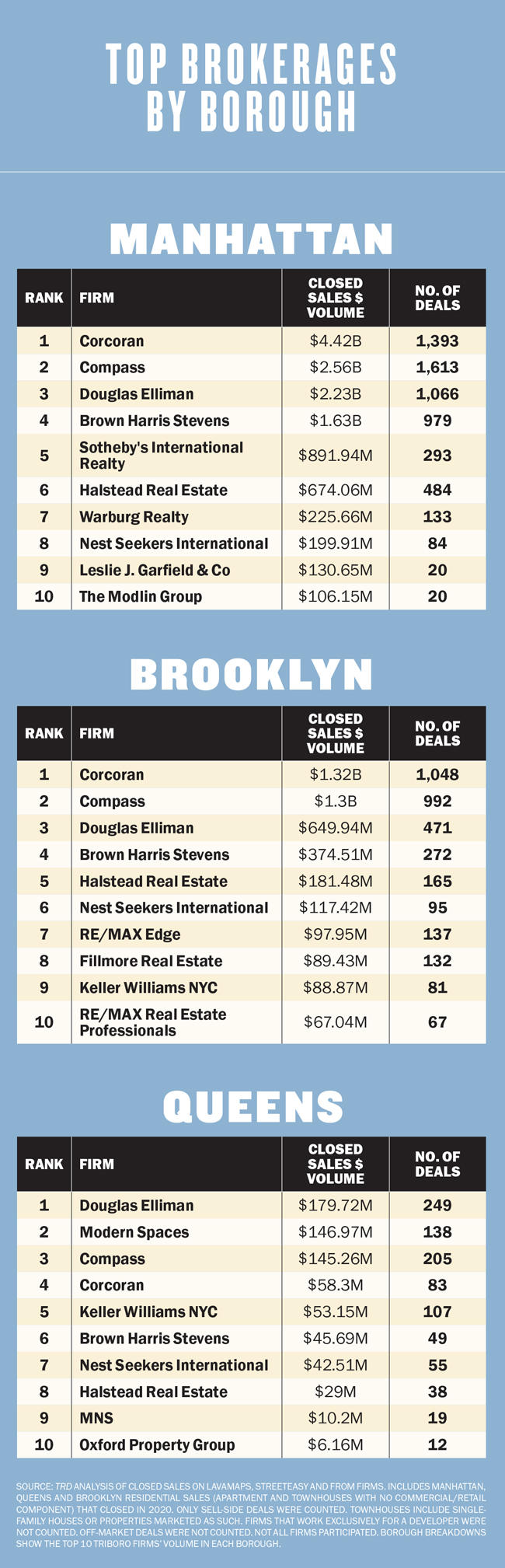

As buyers’ preferences changed — square footage outweighed location, outdoor space trumped views and the appeal of shared amenities evaporated — Manhattan’s market took a particularly big hit. Sales in the borough fell 39 percent to $14.05 billion last year among the city’s top 25 firms, down from $23.1 billion in 2019. The borough’s sales volume took such a nosedive in early 2020 that the industry was applauding its fourth quarter for being “only” 20 percent below 2019’s figures.

The plunge was due in part to a drop-off in overall transactions, but also because of a sharp contraction of the luxury market. Buyers were able to extract hefty concessions on the deals that did get done.

The so-called “Covid discount” was as high as 17 percent for the most expensive homes on the market, according to Liebman. For deals hammered out in 2020, some sellers ate losses of up to 50 percent, as happened with a recent condo sale at One57 on Billionaires’ Row.

Discounts didn’t affect the major new development sales closing last year that were negotiated before the pandemic. Vornado Realty Trust’s 220 Central Park South, where Corcoran’s new development division Corcoran Sunshine handled sales, saw a steady stream of eight-figure closings.

But leave it to the city’s ever-optimistic residential brokers to find a way to spin upheaval into upside.

Bess Freedman, CEO of Brown Harris Stevens, said the sales pitch to buyers is simple:

“This is the time if you want to throw down your flag,” said Freedman. “This is when you get real value.”

“This is a very value-oriented market,” said Liebman. “People took advantage of very, very low interest rates, very high inventory and reduced prices. So the smart buyers continued to be opportunistic during the pandemic.”

Steven James, Douglas Elliman’s New York CEO and president, agreed. “The city is becoming more affordable,” he said. Pointing to the surge in Manhattan condo sales in the fourth quarter of 2020, James said, “I’m finally feeling positive.”

James has navigated various big challenges during his four decades in the business, “[but] this is the first time honestly in all those years that I’ve experienced what I truly believe was a huge, huge cataclysmic change,” he said.

James has navigated various big challenges during his four decades in the business, “[but] this is the first time honestly in all those years that I’ve experienced what I truly believe was a huge, huge cataclysmic change,” he said.

Island hopping

For Jed Garfield, the pandemic brought his business to new places — namely, Brooklyn.

The broker, whose firm Leslie J. Garfield only sells townhouses, used to make only a few visits across the East River each year. But in 2020, he ventured to Brooklyn multiple times every month, often with high-net-worth clients who wanted to trade in their Manhattan townhouses for homes in Brooklyn.

“It’s like you go there and I feel like I’m in Manhattan on the Upper East Side in the 1970s,” said Garfield. “People still play out on the street there, there are still corner delicatessens — good ones.”

Garfield said that in 2020 deals in Brooklyn Heights and other areas in the borough significantly picked up, while deals in Manhattan’s Upper East Side and Upper West Side submarkets declined. He estimated that deal volume in both of those neighborhoods was down about 35 percent last year.

Still, 2021 has brought renewed interest to Manhattan’s housing market, with new contracts signed in the borough hitting levels not seen since the 2015 peak, according to Serhant, the firm founded by Ryan Serhant in September. His new venture did not make the ranking this year, but his alma mater, Nest Seekers International, landed the No. 7 spot, unchanged from last year’s ranking.

It’s anyone’s guess how lasting the new “work from anywhere” world will be, but over the first nine months of the pandemic, people’s housing preferences shifted, and so too did the market.

In this year’s ranking, eight of the city’s top 25 firms did a third or more of their 2020 sales volume in Brooklyn. And four of those firms did nearly all their business in the borough. Those firms — which had never made TRD’s annual ranking before — included RE/MAX Edge, Fillmore Real Estate and Momentum Real Estate.

Among the top firms, Compass reported the biggest year-over-year increase last year in Brooklyn, where its sales soared nearly 133 percent to $1.3 billion, up from $560 million in 2019. Brown Harris Stevens reported a nearly 83 percent bump in Brooklyn business, at more than $374.5 million in 2020, up from $205 million in 2019. This boost was partly attributable to the firm’s June 2020 merger with Halstead, which made a higher proportion of its sales in the borough — including more than $181 million prior to the merger.

Many firms that made the ranking also saw a year-over-year increase in sales volume in Queens. Elliman reported the highest sales volume in that borough at $179.7 million — up 33.5 percent from 2019. Long Island City-based firm Modern Spaces had $146.97 million in sales, up from $90.3 million in 2019. And Compass rounded out the top three in the borough, nearly tripling its Queens sales to reach a $145 million total.

The new (virtual) reality

Buyer preferences and locations weren’t the only shifts in the city’s brokerage business. In order to keep themselves and their clients safe and comply with regulations, agents had to adopt new marketing tactics.

Agents turned to virtual home tours during New York’s three-month ban on in-person showings, whether pre-filmed or shown in real time over FaceTime. The widespread adoption of virtual tours has actually become a bright spot for agents and clients, allowing both parties to determine their interest before committing to an in-person showing.

Many agents and executives believe virtual tours will remain a fixture even after concerns over the coronavirus fade. Corcoran’s Liebman even suggested that the pandemic may have killed the industry’s iconic open house, saying that many agents will opt to continue doing showings virtually before setting up in-person tours by appointment.

There’s also a new flexibility within firms with the normalization of video conferencing. Elliman’s James admitted having strong reservations. “I thought, ‘I’ll never be able to do this,’” he recalled. But he said that on small-group video calls, he began hearing from sales managers who had never spoken up in the large all-hands meetings the firm previously held in person.

Despite the dramatic changes of last year, most firms have committed to holding on to their New York offices and say they’re betting on the city and corporate life returning to what it once was — sooner or later.

Corcoran is renovating a new headquarters on Madison Avenue, while Elliman and Compass say they’re retaining their entire office footprint. BHS cut down on office space formerly used by its sister firm Halstead since their merger, but Freedman says that for cultural reasons, there won’t be further consolidation.

“It’s not the same when you work at home,” she said. “I think we benefit by being together.”

Backing up its talk with money, Sotheby’s International Realty launched its first-ever TV commercial in February — an artsy ode to New York running on Hulu and Link NYC digital kiosks, showing New Yorkers moving through the city in flattering sunlight interspersed with shots of Manhattan’s skyline. The firm closed $924.9 million in sales last year, down 37.5 percent from $1.48 billion in 2019.

“We have a 38,000-square-foot [office at] 650 Madison, so we have a heavy, heavy investment in this city and we expect it to come back,” said Philip White, CEO of the firm.

All hands on deck

The response to the pandemic also undermined the brokerage industry in a more indirect way than scaring off buyers or banning open houses.

Under the federal CARES Act, independent contractors like residential brokerage agents were able to qualify for unemployment payments for the first time ever — and in New York, they could claim the expanded benefits even if they stopped working voluntarily due to concerns about the pandemic. So, faced with daunting obstacles and a bleak market, nearly 4,000 agents terminated their real estate licenses last year.

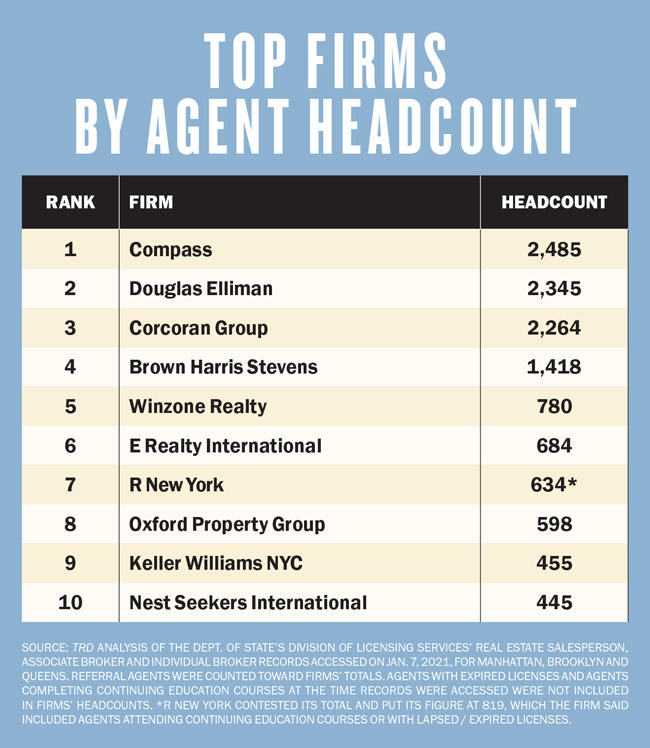

The drop in state licensees didn’t translate into big declines in headcount at the city’s major firms, however, which continued to recruit vigorously after some start-of-year cuts.

The drop in state licensees didn’t translate into big declines in headcount at the city’s major firms, however, which continued to recruit vigorously after some start-of-year cuts.

Compass overtook Elliman as the largest brokerage in the city with 2,485 agents, up nearly 18 percent from 2,112 in 2019. Elliman’s numbers were down slightly to 2,345 from 2,460. No. 3-ranked Corcoran had a 33 percent boost in headcount with 2,264 agents, up from 1,697 agents the previous year, but that was due to its January 2020 merger with sister company Citi Habitats. The combined company had 2,420 agents at the time of the merger.

Many agents worked harder for less business, even while putting themselves at risk. That led R New York, a 100 percent commission firm, to make a big recruiting push, according to the firm’s president, Stefani Berkin.

In the fall, the company added a “calculator” to its website that allows agents to crunch the numbers and compare how much they’d take home if they worked at R New York versus their current brokerage. Since then, Berkin said, the firm has seen recruitment levels grow, peaking in December when more than 20 agents joined.

“When agents are having a tough time, every dollar really counts, and if they’re doing five deals instead of 15 deals, or one deal instead of 10 deals … every dollar counts,” said Berkin. “So, people really are appreciating what the 100 percent commission model means and how far it actually goes.”

Despite the recruitment push, R New York saw its headcount decrease 18 percent last year to 634 agents. Berkin contests the figure, arguing that R New York has 819 agents — counting brokers who are either in the process of joining the firm or completing training to renew lapsed licenses.

But size isn’t everything. Smaller boutique firms that focus on high-end properties once again had higher average deal prices than the big players.

Leslie J. Garfield was the top firm in the city with an average deal size of over $5.8 million, followed closely by the Modlin Group at $5.3 million. Sotheby’s was third with just over $3 million. Among the larger firms, Corcoran fared the best with an average deal size of $2.29 million, while Elliman’s average deal was $1.7 million and Compass’ was $1.4 million.

White of Sotheby’s said the average sale price per agent is the metric his firm tracks.

“We’ve never gone out to be the biggest firm in New York City,” he said. “We focus more on productivity per agent than the size of our company.”

Garfield, whose firm made $174.76 million worth of sales in 30 deals last year, agreed.

“I really like the fact that we don’t have any dead weight,” he said. “If you look at a place like Douglas Elliman, they’ve got a lot of dead weight. You look at Compass, they’ve got a lot of dead weight. If they didn’t, they would be doing more business per broker than any other brokerage,” Garfield added.

Seller’s market — for firms

Though deals for residential units took a hit, deals for residential firms did not. The year saw a wave of M&A transactions across brokerage.

While most bigger firms say they’re still on the lookout for merger opportunities, the smaller shops high on TRD’s ranking say the incentive to sell is low.

Garfield said he fields offers every six months or so, but he doesn’t see how being part of a larger firm equates to more business for a highly specialized outfit like his.

Frederick Peters of Warburg — which placed eighth on the ranking with $238 million in sales — said he has no motivation to sell either, arguing that the presence of smaller firms is best for the industry as a whole. He noted that price-fixing and price wars that increase costs for consumers are hallmarks of industries dominated by big companies.

“If it becomes impossible to compete or succeed without multiple millions in venture funding, that will be a sad day for the entrepreneurial spirit in our country,” Peters said in a statement.

Peters’ comment raises the concern many industry leaders and agents have about Compass, which has raised $1.5 billion in venture capital since it was founded in 2012. Like many other VC-backed firms, it has yet to turn a profit, and some in the industry wonder if its loss-leading growth strategy can ever result in a sustainable business model.

In the prospectus Compass filed as part of its initial public offering, the brokerage disclosed that it lost $270 million last year and has lost a total of $1.1 billion since 2016. Its revenue, however, was up 56 percent last year, reaching $3.7 billion compared to $2.4 billion in 2019.

Compass’ IPO will mean an infusion of cash, which the firm — the largest brokerage in the city by headcount — will likely spend on even further growth.

Once Compass goes public, all three of the city’s biggest brokerages will be publicly held and ultimately answerable to their shareholders.

Freedman at BHS, which will become the largest privately held brokerage in the city, said retaining flexibility gives firms like hers a competitive advantage over the big three.

“We have the freedom to build a company that we believe in,” she said.