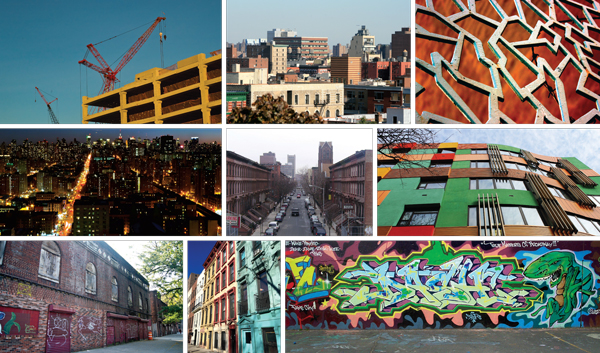

East Harlem wears its heritage on its façades. In the heart of El Barrio, a James De La Vega painting at 104th Street and Third Avenue pays tribute to Puerto Rican poet Pedro Pietri, a mural of Che Guevara and Pedro Albizu Campos stands out one block northeast at 105th Street, and a passage by W.E.B. Du Bois is sprayed on a brick wall on 110th Street. “We are the supermen who sit idly by,” it begins.

And like most New York City neighborhoods, East Harlem is in perpetual transition — evidenced by the half-built condominiums wedged between brownstones on Langston Hughes’ old block, the luxury rentals expanding above the 96th Street border and the specialty coffee shops sweeping eastward towards Fifth Avenue.

“[In Manhattan], you can’t push any further south because there’s water, or west because there’s water,” said David Blumenfeld, whose Blumenfeld Development Group has been active in the area since the early 1990s. “The only way for development to expand is north.”

The remaking of the neighborhood seems inevitable, and real estate players are eager to catch the wave before it swells. But while the harbingers of change are present — the Second Avenue subway to the south and a brand-new Whole Foods to the west — that change is more anticipated than achieved.

Several large residential projects are awaiting a green light, while a controversial, 88-block rezoning that would allow for 30-story towers on the corridors along Park, Lexington and Third avenues is slated to enter the approval process this spring. In the meantime, several local development sites remain unused, and the city is looking to push through key projects that would bring more housing, jobs and commerce to the neighborhood.

One notable project under construction is Gotham East, an 11-story rental building at 149 East 125th Street — near the neighborhood’s Metro-North station — designed by Bjarke Ingels and slated for completion in 2018. Blumenfeld Development broke ground on the site last October, and 20 percent of the 233-unit building will be priced below market rate.

East Harlem, with one of Manhattan’s lowest median incomes, was designated in 2015 as one of several neighborhoods to be rezoned under Mayor Bill de Blasio’s affordable-housing mandate. After a year of community outreach, the Department of City Planning presented its rezoning plan in the fall of 2016 and is scheduled to begin the lengthy approval process — which must go through the community board and the City Council — in April.

But not all developers are waiting for the rezoning. While massive residential projects are few and far between, boutique condos and luxury rentals are quickly rising throughout the neighborhood. East Harlem’s median home price has risen 12 percent to $815,000 in the past year, according to GFI Realty Services, while its median rent, at $2,400, has edged above Central and West Harlem.

“It’s kind of primed for the taking,” said retail leasing agent Seth Kessler, whose firm, the Shopping Center Group, brought the new Whole Foods to Lenox Avenue.

Marcus & Millichap broker Seth Glasser noted that what trades for $800 a square foot below the 96th Street border can trade for $400 above. “In this neighborhood, you’re getting a significant discount [compared] to only a few blocks south,” he said. “If you’re able to wait and bank on the gentrification.”

Zach Sharaga, a Bronx native who opened a coffee shop just east of Second Avenue, said he and his partner were drawn by the opportunity to be “trailblazers” in the area. The two opened their shop, Dear Mama, on the ground floor of a newly completed rental building where a 900-square-foot one-bedroom rents for $3,050. “It’s still island-of-Manhattan rent,” Sharaga noted. “But now we set the bar.”

Along 125th Street — which the city upzoned in 2008 — potentially transformative sites have been snapped up by major New York City real estate players, including Gary Barnett and the Durst family. But several of those projects are on hold indefinitely.

Across from Blumenfeld Development’s rental building on East 125th Street, Barnett has owned a block-long Pathmark site since 2014, and the Durst Organization paid $91 million for a site at the corner of Park Avenue last August. Neither developer has announced plans for the properties.

Outside the rezoning perimeter, a 1,100-unit rental complex between East 117th and 119th streets on the East River, another Blumenfeld Development project is also in limbo. The developer laid the groundwork for the towers — the tallest of which would rise 41 stories above the East River Plaza shopping mall — more than a decade ago. Now the project is pending the renewal of the 421a program, Blumenfeld explained.

Another planned 1,100-unit complex, at East 96th Street, is awaiting land-use approval. The block-long project by the real estate investment trust AvalonBay Communities in partnership with the city’s Education Construction Fund will include a 68-story tower and three public high schools.

The city is also moving forward with several of its own large residential, commercial and public projects. Among them are a $238 million cancer treatment center and the conversion of an MTA bus depot into a 730-unit housing complex that will include an outdoor memorial for a historic African burial ground on the site.

Some local residents are skeptical that the public benefits offered in the private and city-subsidized projects will compensate for the surge of development in the neighborhood, especially if the rezoning goes through. Primary among the concerns is that the affordable components won’t be enough to mitigate the displacement of longtime community members by the influx of higher-income residents.

At a Community Board meeting regarding the East 96th Street development, residents expressed dismay at the project’s size. “Everybody wants new schools, but nobody wants a 68-story building, except Avalon,” one resident lamented.

Community Board 11 Chair Diane Colliers, however, argued that the incoming projects could benefit the community in the long run. “We have to think about our future and the children,” she said. “That they are able to benefit, not only from housing, but from education, transportation and all the other things that contribute to the quality of life.”

1.

East River Plaza

East River Plaza

Blumenfeld Development & Forest City Ratner

Blumenfeld Development and Forest City Ratner are planning to build a three-tower, 1,100-unit rental complex atop the East River Plaza mall — a project that is more than 20 years in the making.

Blumenfeld Development constructed the 500,000-square-foot big-box mall, home to Target, Costco and Marshalls, with the infrastructure for future residential towers underneath it.

“We knew, at some point, there would be demand for it,” said David Blumenfeld, a principal at the development firm, which acquired the site between East 117th and 119th streets in the early 1990s.

The retail plaza opened in 2009, and in 2014, the developers revealed their plans for three residential towers of varying heights, the tallest of which would reach 41 stories, designed by TEN Arquitectos.

The area has already been rezoned for residential use, but there will still need to be a ULURP review process. Blumenfeld Development is waiting on the renewal of 421a before moving forward.

2.

Sendero Verde

Sendero Verde

Jonathan Rose & L+M

In January, the city tapped Jonathan Rose Companies to partner with L+M Development for the construction of Sendero Verde, a 655-unit affordable housing project on a block-long city-owned site.

The 751,000-square-foot complex, located between Madison and Park avenues at East 111th Street, will include a slew of public facilities, including a YMCA, a medical center operated by Mount Sinai, a home for the neighborhood nonprofit Union Settlement and space for four community gardens that the development will displace.

All 655 units are to be rentregulated and will target a range of income levels, beginning with families of three earning up to $24,480. However, the highest tier, for families of three earning $106,000 or above, will be more expensive than market-rate apartments in the neighborhood.

3.

321 E. 96 St.

AvalonBay & NYC Educational Construction Fund

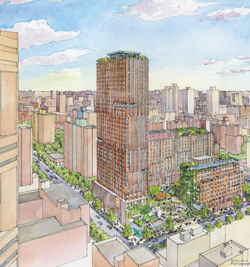

The Virginia-based REIT AvalonBay Communities is teaming up with the city’s Educational Construction Fund to develop a block-long complex on East 96th Street, which will include a 68-story tower with 1,100 rental units and three public high schools.

The 1.3 million-square-foot complex, slated for completion in 2023, will replace the School of Cooperative Technical Education — which sits across from the new Second Avenue subway station. The project’s residential units will be 30 percent affordable.

Despite opposition from a number of East Harlem residents, Community Board 11 greenlighted the project in March, and the developers can proceed to the next step in the ULURP process. The primary concern among locals is that the area can’t support a mass influx of students and residents at an already congested intersection, which is still adjusting to the increased traffic from the new subway.

“We didn’t set out to build a 68-story tower,” said Martin Piazzola, senior vice president of development at AvalonBay, who noted that the project evolved in response to the community’s requests. “You’d be hard-pressed to find a development with more public benefits,” he added.

4.

Gotham East

Gotham East

Blumenfeld Development

“Here we are in the heart of a very lively and transforming neighborhood,” Bjarke Ingels said at the groundbreaking in October for the 11-story rental building his firm designed in East Harlem. “We had to think differently.”

Blumenfeld Development’s 275,566-square-foot project at 149 East 125th Street will contain 233 apartments, 20 percent of which will be designated as affordable.

Renderings show that the building will have a gray façade that undulates along East 125th Street, which Ingels says was inspired by “an elephant skin.” A portion of the building will cantilever over an existing structure on East 126th Street.

A 2008 rezoning allowed the developer to build as-of-right. “You’re going to see a change on 125th Street,” said Blumenfeld, who emphasized that the neighborhood has been underserved. “Our leap of faith spurred people like Extell and Durst to buy their sites,” he added.