Masayoshi Son responds to swagger.

It’s something only a handful of New York real estate executives may have realized about the 60-year-old SoftBank founder and CEO, who has poured billions into a slew of tech-focused startups over the last few years.

The Japanese billionaire, who prefers to meet with these potential recipients one on one, looks for extreme confidence and a bold vision behind the companies he invests in, according to multiple sources privy to the exchanges.

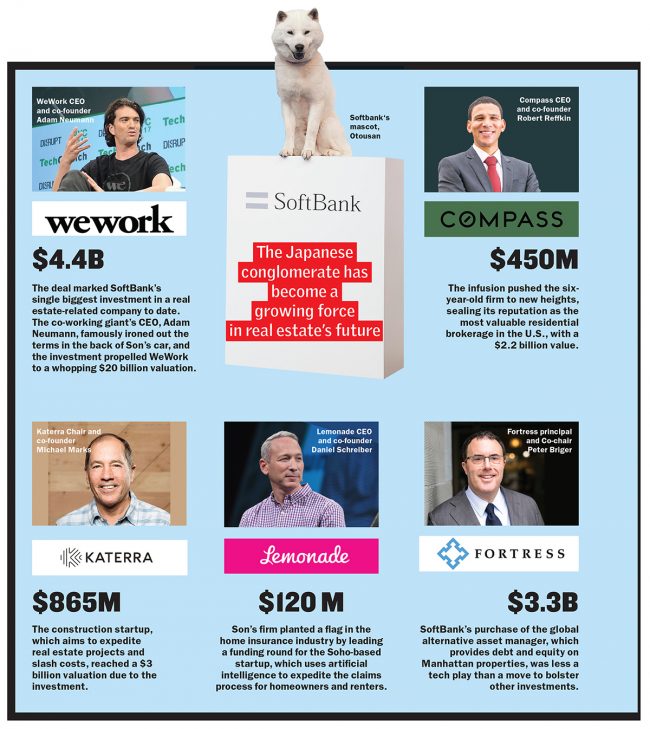

Those talks have gone down both in New York and overseas, and typically stretch over the course of several months. Perhaps the most famous meet-and-greet-turned-megainvestment was in late 2016, when Son impulsively penciled out a game-changing $4.4 billion deal in the backseat of his car with WeWork co-founder and CEO Adam Neumann. That funding propelled the co-working giant to a $20 billion valuation, as Forbes reported.

The eccentric Japanese native of Korean descent, short and balding, directly controls the fate of the companies he invests in and indirectly dictates the market for their rivals. Son is also now the richest person in Japan, with a net worth pegged by Forbes at $22.7 billion.

With the recent creation of SoftBank’s nearly $100 billion Vision Fund, the Japanese telecommunications giant is making investments that threaten to overhaul several industries from ride sharing to robotics — and even dog walking. But its interest in real estate is especially pronounced.

In 2017 alone, SoftBank made roughly 100 investments through the fund and other platforms, with a combined value of $36 billion, in companies such as Uber and Slack Technologies, according to data from research firm Prequin. Nearly $6 billion of that was pumped into budding real estate firms Compass, WeWork, Katerra and Lemonade. Separately, the conglomerate acquired the New York-based asset management firm Fortress Investment Group in a $3.3 billion all-cash deal in December.

To get a closer look, The Real Deal spoke to industry players about what these splashy investments mean for the market and which firms might be next to catch SoftBank’s eye.

But Son — who has said he wants the 16-month-old Vision Fund to help further his company’s growth for “300 years” — may have a new dilemma on his hands.

“They have the funds, but their challenge is when to deploy that kind of capital,” said Richard Sarkis, CEO of the real estate data startup Reonomy, which landed $3.7 million in funding from SoftBank in 2014. “They’re kind of in a trap.”

The fund saw a 22 percent return of about $3 billion over a five-month period starting last May, when it closed its first major investment round, SoftBank announced in October. It has already deployed one-third of its capital and is planning another 70 to 100 investments in tech firms in the near future, Vision Fund CEO Rajeev Misra told CNBC in late February. A spokesperson for SoftBank declined to comment for this story.

The fund saw a 22 percent return of about $3 billion over a five-month period starting last May, when it closed its first major investment round, SoftBank announced in October. It has already deployed one-third of its capital and is planning another 70 to 100 investments in tech firms in the near future, Vision Fund CEO Rajeev Misra told CNBC in late February. A spokesperson for SoftBank declined to comment for this story.

“People said [$100 billion] is too much,” Son told the New York Times last year. “I say it’s too little.”

For the young companies that go without SoftBank’s help, the situation creates an almost unpredictable, ultracompetitive environment in which a rival could soar past them at any moment, said Nick Romito, co-founder and CEO of the cloud-based leasing and asset management platform VTS.

“If someone overnight develops a huge war chest, that’s a scary thing,” he said.

“Soft” launch

Son’s unusual past makes it all the more surprising that he’s in such a position of power today. He grew up in a shack with his Korean family on the Japanese island of Kyushu, where his father, Mitsunori Son, worked as a pig farmer and owned a pachinko parlor.

Discrimination against Korean immigrants was widespread in Japan in the 1960s, and even though Mitsunori was ill at the time, he supported Son’s move to the U.S. at the age of 16. The budding entrepreneur attended Serramonte High School in San Mateo County, California, and went on to receive an economics degree from the University of California at Berkeley.

As an apprentice to an older Berkeley student, Son ran a network of video-arcade machines in Northern California that reportedly reeled in tens of thousands of dollars a month. In his mid-20s, he returned to Japan and launched SoftBank. The telecommunications giant is now Japan’s fourth-largest public company, ahead of Toyota, Mitsubishi and NTT — the latter two of which are also active in New York real estate. And while far younger than some of Japan’s oldest hotel and construction companies, which were founded before the year 800, SoftBank has already seen some impressive highs and lows in less than 40 years as a business.

Son founded the Tokyo-based company as a software wholesaler in 1981 and expanded to computer magazine publishing a year later. He then propelled his firm to a $180 billion valuation and became the world’s richest man at the height of the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s. But when the bubble burst, SoftBank took a huge hit and Son himself reportedly lost about $70 billion in a single day. The company’s stock price fell dramatically from $1,865 in 2000 to a mere $14.53 in 2002. It also faced significant losses from its failing Yahoo-branded broadband arm for four years.

It was a dark period for Son. He slept in the office, worked out of the conference room and exercised on a treadmill while holding meetings, according to a 2012 story in the Wall Street Journal. Sometimes, he would invite executives and partners over for late-night meetings that stretched more than eight hours.

“He would ask our people to go to his office at three o’clock in the morning,” Hong Lu, a business partner of Son’s at the time, told the Journal. “You cannot think of him as a normal businessperson.”

The firm rebounded as its founder placed big bets on Japan’s broadband market, and in 2006 SoftBank acquired Vodafone’s telecom carrier unit for $15 billion. The company began generating an annual profit again and in 2008 became the exclusive iPhone carrier in Japan.

Son’s signature prescient move, though, was a $20 million investment in the Chinese e-commerce startup Alibaba Group in 2000. Alibaba now has a market cap of nearly $500 billion, with Son holding a 28 percent stake.

Now Son is knee-deep into another revolutionary investment spree. SoftBank is arguably the first Japanese firm since the 1980s to place bets on U.S. real estate at such a rapid and aggressive pace. Roughly 30 years ago, investors from the island nation collectively spent billions on Manhattan and Los Angeles properties and scooped up trophies such as the Empire State Building and Rockefeller Center.

But with Son, it’s a very different kind of real estate play. Not only is his firm focused on new companies rather than physical assets, its Vision Fund is backed by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates as well as tech giants including Apple, Qualcomm and Sharp.

While Son has not made any outright acquisitions of New York properties, his impact on the city’s real estate industry through his monster investments is abundant. And he is very hands-on when it comes to determining the Vision Fund’s recipients and how its contributions are later used.

The fund, which is essentially a huge private equity player, takes a 20 to 40 percent stake in the groups it backs. It also often supplies a board member and becomes top shareholder at those companies, giving SoftBank and its Vision Fund more say over its investees’ decisions.

The fund will give at least $100 million if it likes a company, but it prefers to keep contributions north of $250 million, sources said. And Son personally holds just over 20 percent of the parent company, giving him a crucial say in each major decision.

“They become a vote at the table,” said Riggs Kubiak, CEO of Honest Buildings, which to date has not received any funding from SoftBank. “In general, you want to be very careful about who that is.”

Early bets

One of Son’s first known investments in U.S. real estate startups was the Reonomy deal. Josh Guttman, a venture capitalist who then focused on early-stage investments for U.S. affiliate SoftBank Capital, had heard about the newly created real estate data provider from a fellow investor in December 2013 and cold-emailed Sarkis.

The two first met at a Birch Coffee shop in NoMad, and just a few months later SoftBank — then seen as a middle-market player in the venture capital world — took a chance on Reonomy with a $3.7 million Series A investment it led with four return backers that included Resolute Ventures and High Peaks Venture Partners.

The dollar amount is a far cry from the caliber of the Japanese firm’s latest real estate plays, but so is the SoftBank of then versus now. “Not one molecule was foreshadowing the behemoth it would become,” Sarkis said.

SoftBank also took part in an another Reonomy funding round in 2015 totaling $13 million. That same year, Son’s firm led a $1 billion Series E investment (pre-Vision Fund) in the San Francisco-based online lender Social Finance, also known as SoFi.

SoftBank also took part in an another Reonomy funding round in 2015 totaling $13 million. That same year, Son’s firm led a $1 billion Series E investment (pre-Vision Fund) in the San Francisco-based online lender Social Finance, also known as SoFi.

While Reonomy, which has raised nearly $40 million since it launched, is still worlds away from being a giant in its field like WeWork or Compass, its continuous ties to SoftBank appear to have paid off. In February, the five-year-old data startup landed an additional $16 million from Bain Capital Ventures and partnered with newly public commercial brokerage Newmark Knight Frank.

Sarkis said SoftBank remains hands-on with company matters such as business strategy and recruiting even after it makes its investment. “Having a board seat is already a pretty big commitment,” Sarkis said.

In addition to Reonomy, Guttman, who now runs his own company, Morris & Company, spearheaded SoftBank’s investment in the construction tech startup FieldLens in 2014 as part of an $8 million Series A round. WeWork — in which SoftBank now technically has a 20 percent stake — bought FieldLens last year for an undisclosed price.

“The way a $4 billion investment gets made is not that different from the way a $4 million investment gets made,” Guttman said. “Getting a hard-on over the dollar amount is not really the point. The organization that made the investment in Reonomy is different.”

These days, for instance, he and other sources said there is little point in startups pitching to SoftBank for funding. Son and his team now handpick nearly all of the companies the Vision Fund backs, and they almost always make the first move toward investing.

Regardless of who makes the final call, “vetting takes time,” Guttman said. “You spend months getting to know the company — how they operate — to determine if they’re a good match.”

The right direction?

While SoftBank’s seemingly boundless capital has put the company in a class of its own, its push into real estate is unprecedented — and its recent investments have led some to question the firm’s judgment. Industry sources pointed to a few of those huge funding rounds as unwarranted.

SoftBank’s $450 million infusion in Compass in December, for instance, pushed the six-year-old firm to new heights, sealing its reputation as the most valuable residential brokerage in the U.S., with a $2.2 billion value. Maëlle Gavet, who joined the tech-savvy brokerage as its chief operating officer last year, was a part of the executive team that negotiated the funding. She said investments from SoftBank and Fidelity have instilled better “financial discipline” — since the expectation is for Compass to grow its footprint and pour more money into technology — but would not elaborate.

SoftBank’s investment is expected to bolster the brokerage’s expansion to new locations in 20 major U.S. cities by 2020, per CEO Robert Reffkin, and shorten its path to launching an IPO, according to others. But even months after that funding round, industry sources expressed confusion over the move.

“[The funding] came from somebody who doesn’t understand the residential brokerage business,” said Patrick Carlisle, chief market analyst with the San Francisco-based residential brokerage Paragon Real Estate Group. “They look at the volume of commissions, but they don’t realize most commission money goes straight to agents. Meanwhile, operating costs go up. Compass is throwing around money in large quantities despite being in a very low-margin business.”

Another brokerage operating in a similar space as Compass is Redfin. The Seattle-based firm, which has made recent efforts to represent both buyers and sellers, went public in July and has a market cap of roughly $1.7 billion. Compass’ valuation has already surpassed that of its low-cost competitor, which reported $15 million in losses and $370 million in revenue in 2017.

A key difference between the two is that Redfin charges a below-average listing fee (1.5 percent, and now the company is testing out a 1 percent fee in California). Sources say Compass’s strategy — paying agents sizable bonuses and providing 100 percent commission splits — is a cause for concern when it comes to investment profitability.

Carlisle said the only scenario in which that works is if SoftBank sells its stake “before the market looks at companies’ profit and loss numbers again.”

Other tech-heavy real estate firms such as Zillow (which has a market cap of over $7 billion),Redfin and even CoStar may seem like obvious investment choices for the Japanese conglomerate. But sources pointed out that the Vision Fund has yet to target public companies. If that’s an intentional strategy, those three firms may have already been ruled out.

But given that Compass’ rivals mostly fit the bill for a SoftBank boost, it might only be a matter of time before the competition really heats up for the brokerage.

“The Compass investment was predicated on upgrading an old-style business model with more efficient technology,” said Zach Aarons, an executive at the real estate investment firm Millennium Partners and co-founder of the New York-based tech accelerator and advisory firm MetaProp NYC. “But SoftBank likes the super-disruptive stuff, and Compass is not that.”

Bankrolling disruptors

To attract SoftBank’s attention, a real estate company needs to have a “huge idea,” Aarons said. “SoftBank is not interested in incremental improvements,” he noted.

The single biggest amount Son’s firm has provided to a real estate-related company yet came in August, when it invested $4.4 billion in WeWork. The funding is already making some of WeWork’s loftier plans a reality. The co-working giant has lined up a fancy new headquarters, with the $850 million pending purchase of the Lord & Taylor building at 424 Fifth Avenue in partnership with private equity firm Rhone Group.

And SoftBank’s injection will only further WeWork’s rapid growth. The seven-year-old company has locations in 50 countries and is expected to exceed $2.3 billion in revenues this year, the Times reported. Son, who had been pitched on the fast-growing startup in previous years, was said to have developed a rapport with Neumann and the company’s other co-founder, Miguel McKelvey.

Neumann recalled to Forbes that when the two firms closed their deal in March 2017, Son turned to him and asked: “In a fight, who wins — the smart guy or the crazy guy?”

Neumann chose the latter, and Son said, “You are correct, but you and Miguel are not crazy enough.”

The sentiment perhaps indicates that for Son, it’s not just about dollars and cents.

“Masa is compelled by entrepreneurs,” one industry source told TRD on condition of anonymity due to ongoing ties to SoftBank. “These investments have more to do with entrepreneurism than real estate.”

The Silicon Valley-based startup Katerra, for instance, aims to expedite construction projects and slash costs by providing materials on the site as they’re needed — streamlining the path from manufacturing to development.

The three-year-old company just reached a valuation of more than $3 billion thanks to an $865 million investment led by SoftBank’s Vision Fund in January.

Though Aarons pointed out that Katerra is “trying to disrupt construction technology from just one angle” when there are at least two other angles — 3D printing and autonomous construction vehicles —its objectives still fit the bill.

“Katerra has a very capital-intensive agenda,” he said. “As the company grows, it can have a real impact on housing affordability.”

With that deal in particular, SoftBank proved to be a tastemaker. Google recently began negotiating with Katerra, among other startups, to construct 10,000 apartments at its main campus in Mountain View, California.

SoftBank has also planted a flag in the home insurance industry by leading a $120 million funding round for Lemonade in December. The Soho-based startup uses artificial intelligence to expedite the claims process for homeowners and renters.

Daniel Schreiber, CEO of Lemonade, said that Son and his team share “our conviction that big data and machine learning are set to profoundly remake our entire industry.” After SoftBank’s investment, Lemonade had the means to take the company global, Schreiber said.

And in what would be an even bolder insurance shakeup, SoftBank is negotiating to buy as much as one-third of Zurich-based reinsurer Swiss Re in a $10 billion deal.

The talks suggest a move toward crossover benefits among some of SoftBank’s investments. Sources told the Journal in February, for example, that Son’s firm could offer Swiss Re’s insurance plan to WeWork members.

Likewise, SoftBank has partnered with a construction firm it invests in to serve a common goal. Lendlease, the Australian giant that has become a go-to manager for Billionaires’ Row projects, struck a partnership with SoftBank in October to work on roughly 8,000 U.S. cellular sites. The move allows Lendlease to become a major owner of cell towers alongside SoftBank, which owns about 80 percent of Sprint’s outstanding shares. The companies have each put in $200 million toward the $5 billion venture, with SoftBank’s portion coming directly from the company rather than its Vision Fund. It’s also SoftBank and Lendlease’s first joint investment.

Negotiations primarily went down in person with both firms’ executives in Kansas City, where Sprint is based, according to Murray Woolcock, a Lendlease executive who serves as CEO of the Lendlease Towers venture. SoftBank execs also flew to New York for meetings with Woolcock and his team, he said, but declined to comment further on the meetings.

“Their long-term infrastructure needs and disruptive mindset complement our thinking,” Woolcock said.

Future glimpses

As more entrepreneurs see their dreams realized thanks to SoftBank, the ongoing question is which startups will be next to get a big funding push.

Son has frequently said at conferences and in interviews that a “sparkle” in Jack Ma’s eyes triggered his impulse to back Alibaba, and he has found that sparkle in subsequent investment prospects.

“The Vision Fund is focused on really big opportunities. It’s not an attraction particular to real estate,” said Matt Krna, managing partner of the tech investment fund Princeville Global and a former partner at SoftBank’s U.S. venture capital fund.

But if Son were to target more real estate-related companies, he would look no further than the most well-capitalized, sources said.

Firms such as VTS and the rental listings service Apartment List appear to have funding momentum and operate in a space that SoftBank has not made a true leap into yet — potentially making them ripe for an investment.

VTS, which lets building owners manage their leases and other important data using cloud-based software, merged with its competitor Hightower in a $300 million all-stock deal in 2016.

Romito, who explained that his company is not seeking funding or looking to IPO “anytime soon,” said there are very few startups in the commercial real estate tech space that would be ready for a $200 million investment at the moment.

But there are prospects on the residential side, he and other sources noted. Apartment List, a six-year-old company based in the Bay Area, raised $50 million in Series C funding in January. Representatives for the listings service declined to comment.

Honest Buildings’ Kubiak hopes that once his company reaches an attractive size “in the next two or three years,” SoftBank will consider it for a hefty investment.

“We are 100 percent interested,” Kubiak said. “Companies with the biggest market opportunity should be on SoftBank’s list, and there are a lot of differences between Katerra and Honest Buildings, which is building a marketplace and workflow.”

SoftBank is naturally drawn to opportunities involving “tech-driven companies in large markets that have historically not been adoptive of technology,” Krna said.

On the non-real estate front, some have also speculated that Elon Musk’s Tesla Motors and SpaceX would be logical next big bets for Son’s firm.

And while there’s always a chance that one or more of the Vision Fund-backed startups will fail, SoftBank would sustain little damage from those losses due to the wide range of its investments, according to sources.

“It may be that SoftBank’s strategy is that they can fail 98 percent of the time as long as they strike a gold mine like Alibaba every now and then,” Paragon’s Carlisle said. “And as long as they [do], it indeed all works out.”

The Japanese conglomerate also has plans to diversify its investment portfolio beyond tech-savvy startups. SoftBank’s $3.3 billion purchase of Fortress Investment Group gives it the bandwidth to compete with Wall Street and private equity firms.

Not only does the company now have a large financial subsidiary with more than $36 billion in assets under its belt, it has a model for a new investment entity.

Son’s firm, according to the Times, plans to launch SoftBank Financial Services — a 1,000-person, London-based operation that will invest in private equity firms, hedge funds and distressed debt (see sidebar).

But as Son’s firm keeps making gigantic bets that could severely dislocate industries, the companies that receive a huge boost along the way might suddenly hit a wall or ceiling.

“After a SoftBank investment, there’s no exit for a company like Katerra,” said Aarons. “Either take over the industry or you’re out … there are no companies big enough to buy you anymore.”

For now, the Vision Fund-backed startups in the U.S. have shown no signs of failure. Overseas, however, it’s more of a mixed picture. The Indian budget hospitality chain OYO Rooms, for example, is one of the more troubled companies backed by SoftBank. The five-year-old company, which received a $250 million investment led by Son’s firm in September, has been fighting allegations of data theft in court from its rival Zostel and reported about $50 million in losses for fiscal year 2017.

And while there are no other Japanese firms rivaling SoftBank to back U.S. real estate-related startups, there is plenty of potential for competition from big institutions in other countries. Sovereign wealth funds, in particular, could be the next to emulate what SoftBank has accomplished, sources said. Organizations from China Investment Corporation to the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority may start to move beyond ride sharing — where they have been recently active — toward real estate startups. Such a shift would likely empower the leading rivals to WeWork, Compass and Katerra and further disrupt specialized markets.

Still, SoftBank has a war chest that few others would able to top, and Son’s infatuation with the future is far from the norm when it comes to real estate investment.

“Putting significant amounts of capital to work can scare off the competition. For the Vision Fund, that’s an important part of the strategy,” Krna said. “You need an enormous balance sheet and wherewithal to face off against SoftBank.”

—Kathryn Brenzel contributed reporting.