Since taking office nearly four years ago, Mayor Bill de Blasio has had a love-hate relationship with New York’s real estate industry, to say the least. The Real Deal detailed that ambivalence in a February 2016 cover story, in which real estate execs explained how the mayor sought to extract concessions from developers — a stark contrast to the public-private partnerships Mayor Michael Bloomberg encouraged during the latter part of his tenure.

But leading up to de Blasio’s re-election last month, the mayor took off the gloves and ramped up anti-developer rhetoric in debates and other public appearances. In an interview with New York magazine in September, for example, he expressed a desire to deflate private property rights, telling the reporter: “If I had my druthers, the city government would determine every single plot of land, how development would proceed.”

The statement — in which, one real estate executive told TRD, the mayor “went straight to Chairman Mao” — came amid a barrage of attacks from de Blasio’s opponents, who accused him of having too cozy a relationship with developers and other industry players. Over the past two years, the mayor’s ties to real estate have been at the center of various probes — most notably the Rivington House scandal, in which the city lifted two deed restrictions, allowing the property’s owner to sell the former nursing home to a luxury condo developer for a hefty profit. No criminal charges ever came of the investigation or any others.

“I don’t think we can take [the mayor’s comments on property rights] very seriously,” said Paul Massey, who hoped to run against de Blasio as a Republican but dropped out in June. After all, the real estate industry is “the underpinning of the city’s revenue sources,” he said.

Last year, NYC real estate generated $20.4 billion in taxes, 43 percent of the city’s total intake, according to the Real Estate Board of New York. And construction spending has soared in the last four years, crossing the $40 billion threshold for the first time in the city’s history in 2016, per the New York Building Congress. That high volume of spending is expected to continue over the next few years and climb to $102.6 billion combined in 2018 and 2019.

But in light of the city elections, many real estate players are anxiously surveying the political landscape. Key City Council positions, including speaker and Committee on Land Use and Committee on Housing and Buildings chairs, still need to be filled come January.

Meanwhile, a stronghold of council members is pushing legislation that could put the reins on developers, and the majority of speaker candidates have expressed support for commercial rent control.

The de Blasio administration and City Council “had a great tailwind from real estate,” said David Lombino, managing director at Two Trees Management. “There’s no one who predicts that that will continue for the next four years.”

A call for unity

As council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito gets ready to step down next month, industry sources say her replacement will need to take stronger command of the governing body — especially when it comes to rezoning initiatives under the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program.

While Mark-Viverito found herself even to the left of de Blasio when it came to social issues like immigration and criminal justice, real estate players interviewed for this story zeroed in on her approach more than her agenda.

While Mark-Viverito found herself even to the left of de Blasio when it came to social issues like immigration and criminal justice, real estate players interviewed for this story zeroed in on her approach more than her agenda.

“The less powerful the speaker is, the harder it is to get these rezonings done,” said Jordan Barowitz, who oversees government and media relations for the Durst Organization. “The more parochial the council, the harder it is to accomplish these sort of macro policies.”

While the rezonings of East New York and Far Rockaway passed this year, and East Harlem’s (as of press time) is poised to do so as well, others have dragged on because of local council members’ opposition. The rezoning of East Harlem has stretched out for a year because of community opposition and was nearly held up again before the land use committee voted on density and height restrictions.

Meanwhile, various council members have stood in the way of neighborhood and project-specific rezonings. The rezoning of Flushing was blocked, and plans for a 355-unit residential project in Inwood — half of which would have been affordable — were nixed. BFC Partners’ proposed Bedford-Union Armory redevelopment in Crown Heights has been embroiled in controversy since 2015. Just last month, local council member Laurie Cumbo finally cut a deal with the city and the project’s developer to eliminate condos from the development.

Individual council members are often unwilling to budge on their demands from developers, said Real Estate Board of New York President John Banks. “There seems to be an all-or-nothing mentality,” he said. “That is never going to allow us to build the density we need.”

Outgoing land use chair David Greenfield said that in some cases, what causes a holdup is “member deference.” During a City & State panel last month, he said that the next speaker will need to come up with a clear set of standards for when the council should defer to a neighborhood’s representative on land use issues like MIH rezonings. Otherwise, council members won’t know under which circumstances to align themselves with a local council member’s wishes.

“I think that’s a very dangerous place to go,” Greenfield said. “It will be much worse if we have member deference with exceptions. People won’t be clear what those exceptions are.”

But now, Intro 1685, a bill sponsored by council member Margaret Chin, could give local members even more power over developers. The bill, in its current form, could allow a local council member to fight as-of-right developments in their district that aren’t required to pass through the typical land review process. The legislation has made its way through the City Council and is awaiting de Blasio’s approval.

“The bill to submit a complete land use application, without having to jump through bureaucratic hoops, must be allowed to give our communities a fighting chance in this war against overdevelopment,” Chin told Politico in early November. “If the Real Estate Board of New York is afraid of this bill — good!”

Massey, who serves as president of New York investment sales at Cushman & Wakefield, said such policies could have a chilling effect on development throughout the five boroughs.

“If every development is a one-off negotiation with the city, business will come to a grinding halt,” he said. “We need as-of-right development because we need housing on a scale that no one’s talking about.”

Greenfield, too, said that he expects the council to block more projects in coming years.

Greenfield, too, said that he expects the council to block more projects in coming years.

Even without the behind-the-scenes operation of the City Council, construction is already starting to slow and developers are pulling back from the market.

“I think that this is a very, very dangerous time for New York City real estate and the city’s economy in general,” said developer Don Peebles, who has previously expressed interest in running for mayor. “This is the first time in my career where I have not seen the New York City real estate market correlating with the stock market.”

Regulations and reforms

With a giant question mark over who the next council speaker and land use chair will be, there is still a slew of regulatory issues the industry has to worry about.

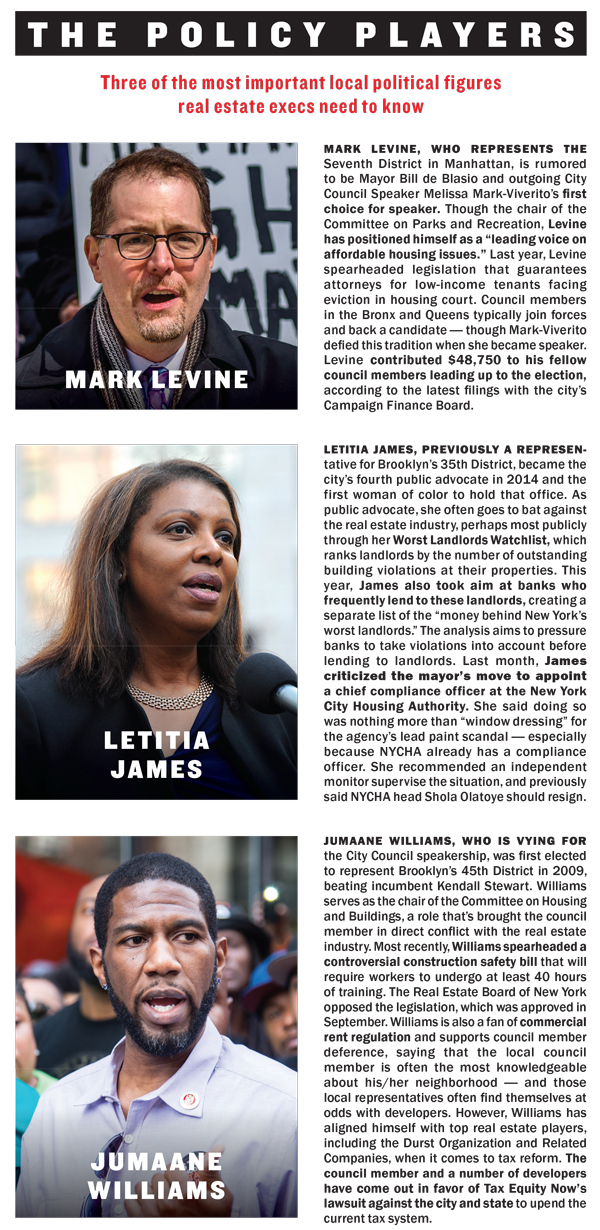

One jarring proposal for the real estate industry is commercial rent control to help mom-and-pop shops compete with chain stores in the city. Six of the eight speaker candidates — including Corey Johnson, Mark Levine and Jumaane Williams — have come out in favor of the initiative.

REBNY’s Banks referred to the measure as unconstitutional, saying that it “represents the taking of property without due process.”

“For a business that is not viable economically, controlling the rent only delays the inevitable outcome,” he said, calling market-rate rents “part of the normal economic pressures of supply and demand.”

Alicia Glen, deputy mayor for housing and economic development, told TRD that the administration is exploring different ways to address the high number of retail vacancies in the city, but said she doesn’t see rent control as a viable solution in the commercial market.

“We are seeing a structural shift in the retail environment,” Glen noted. “We’re aware of the issue, and we are talking to all sorts of stakeholders, to do something that really makes sense.”

Meanwhile, on the tax front, the industry and the mayor are in favor of scrapping the current system — but what that reform would look like remains unclear.

Speaking to the Association for a Better New York on Nov. 6, de Blasio once again vowed to reform the city’s “wildly inconsistent” property tax system. The mayor had pledged to take up the thorny issue when he ran for office in 2014 but never addressed it during his first term.

“There’s a reason that this issue hasn’t been touched by elected officials in 30 years,” Barowitz said. “Not only is it politically unpalatable, but it takes action at both the local and state level.”

The Durst Organization and other developer heavyweights, including Silverstein Properties, RXR Realty and Related Companies, have publicly supported a lawsuit filed by the reform coalition Tax Equity Now New York against the city and state, seeking to overhaul the system.

Luxury condos and co-ops are taxed at a lower rate than moderately priced ones under the existing code, while rental properties carry a larger portion of the tax burden than single-family homes. The coalition’s lawsuit seeks to lower taxes for office, retail, hotel and rental properties — though it’s unclear how reform would exactly shake out.

De Blasio, who opposes the suit, has argued that “when you put things in a hand of a judge, you never know where it’s going.”

While there is virtually no consensus on how to rewrite the city’s property tax laws, many real estate executives favor reform. They are not, however, sold on the mayor’s proposed millionaires’ tax. The proposal calls for a 0.5 percent increase on the income tax rate for individuals who earn more than $500,000 and for couples who make $1 million or more. Revenue from the tax — projected to reach $820 million by 2022 — would go to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Peebles said such a tax, especially if combined with the latest reforms proposed by the federal government, could lead to a “mass exodus.”

“Wealthy people are mobile. It’s the poor and the middle class who are stuck and generally can’t relocate,” he said. “If he imposes any of these cockamamie tax policies, people will leave.”

But Glen argued that the administration needs a stronger revenue stream to support the city’s mass transit, which has suffered from storm damage, major delays and a recent decline in ridership. Average subway ridership during weekdays fell to 5.712 million this September from 5.817 million 12 months prior, according to the New York Times.

“Without mass transit, the whole thing goes down the drain,” she said. “I personally don’t believe [the millionaires’ tax] is going to send people fleeing to Florida.”

Co-dependency

Two weeks before the polls opened, de Blasio took a pre-election victory lap. He boasted that his affordable housing program — the focal point of his administration — is two years ahead of schedule and decided to raise the stakes. The mayor promised to create or preserve an additional 100,000 affordable housing units by 2026, bringing the grand total to 300,000.

There’s a rocky road ahead for de Blasio’s housing program. The mayor plans on doubling the budget for affordable housing construction, which will total $82.6 billion instead of the $41 billion previously estimated, according to Politico. Moreover, to make the initiative work, he has to rely on programs and policies that are out of his control.

As of press time, the House version of the GOP’s federal tax reform bill, for instance, called for the elimination of private activity bonds — a major funding source for affordable housing across the country. And the New York State Housing Finance Agency quietly stopped issuing tax-exempt bonds for 80/20 projects through at least 2018.

Alan Weiner, who heads Wells Fargo’s multifamily capital group, noted that the private activity bonds fill an important equity gap in financing affordable housing projects. Without them, the money will need to come either from city subsidies or out of the developers’ pockets.

“Obviously, it’s laudable that [de Blasio] is committed to more housing that’s needed,” he said. “That’s going to mean more money going from the city, but you also need the cooperation from the state and the feds.”

Since the success of the mayor’s housing plan relies so heavily on the private sector, many developers take his criticisms of the industry — including his declaration that landlords don’t own the city — with a grain of salt. Some industry players also noted that de Blasio, who has positioned himself as a progressive Democrat, possibly has his eye on the 2020 presidential election.

Lombino said that while the mayor doesn’t have a “personal affinity” for the real estate industry, he knows it’s essential to making his housing plan work.

“He sees the market as a necessary evil to achieve his goals on affordability,” Lombino said. “I think it’s always been that way. It’s not like anyone’s asking for handouts. We’re asking for predictability and fairness and trying to avoid mandates that make us less efficient and raise the sky-high cost of building here.”