A high-profile, starchitect-designed homeless and affordable housing development slated to rise near Venice Beach has provoked fierce opposition for years.

The pushback against the Reese-Davidson Community until now has come from a vocal group of residents of the artsy, canal-laced colony who see the project as an ugly, wasteful initiative that will restrict public beach access and denigrate the neighborhood.

Now opponents have gained a surprising ally who holds the potential to cut through the noise: a granddaughter of one of the men whose name is on the Reese-Davidson project.

“It is disrespectful to my grandfather, my family, the Black community and all who have seen your false and misleading project descriptions that you began using my [grandfather’s] name years before you ever contacted me,” Sonya Reese Greenland wrote in late October to the project developers. “My grandfather would be appalled” by the project, she added.

Design resume

The 106,000-square-foot complex was first proposed years ago and is designed by Eric Owen Moss Architects, the acclaimed Culver City-based firm that’s responsible for major postmodern projects including the Guggenheim Helsinki, Queens Museum and The Wrapper, the 17-story curved steel building rising above the La Cienega Metro Station.

It’s slated to rise on a three-acre site in the heart of Venice, near the entrance to the Venice Canals. The site, owned by the City of L.A., is currently a beach parking lot, and lies just a couple blocks from the southern end of the busy Venice Boardwalk.

Plans include 140 units of affordable and supportive housing, with 50% of those units allocated for the formerly homeless, 25% for low-income artists and 25% for other low-income households. In line with the supportive housing model, it will also include full-time staff.

Reese Greenland wrote that she was eventually contacted about the community and the developers’ intention to name it partly after her grandfather, Arthur Reese, which was intended as an honor. But the plans described to Reese Greenland bore no resemblance to what has been advancing through approvals, she contends. She wrote the letter “to demand” that her family name be immediately removed from the project, and she also wants “a full public apology.”

Bohemian history

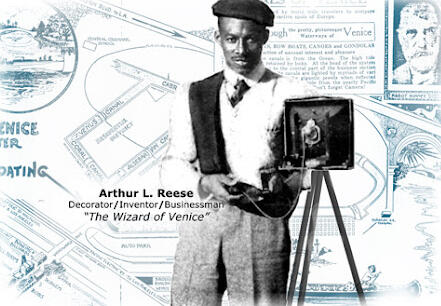

Arthur Reese was an inventor and businessman who in the early 20th century became the first Black person to live and work in Venice, which formed as an independent municipality and was later incorporated into the City of Los Angeles.

Arthur L. Reese (Arthur L. Reese Family Archives)

Reese helped shape the character of what would become among the most famous bohemian enclaves in the U.S. Upon arriving in a still-segregated Venice, he was first hired as a janitor by the company owned by Abbot Kinney — Venice’s ambitious founder — then rose to become the city’s decorator. He was also an entrepreneur and the young city’s first Black property owner.

Reese Greenland is vice president of the Venice Historical Society and has served as her grandfather’s biographer and trustee of the Arthur L. Reese Family Archive. She published a book about him and his work with Kinney in 2006.

“I think in their own ways, they were both visionaries, Mr. Kinney and Mr. Reese,” she told NPR in 2005.

The project is also named for Rick Davidson, an architect and social advocate who cofounded Venice Community Housing, one of the project’s two developers. Reese Greenland’s letter was first reported by the Westside Current; interview requests for Reese Greenland through the Venice Historical Society went unanswered.

Matter of access

Reese Greenland contends in her letter that her grandfather would oppose the project, among other reasons, because of its cost and the large amount of space it will occupy, arguing it would create congestion and infringe on public access to the beach.

After Reese Greenland’s letter was published Evan Hines, the son of Gregory Hines – a Tony Award-winning choreographer, dancer and actor who lived in Venice and was intended to be the namesake of the project’s community arts center –also demanded the removal of that family name.

How the project’s two nonprofit developers plan to respond to the objections, if at all, is unclear. Becky Dennison, the executive director of Venice Community Housing, did not respond to an interview request.

Read more

But to project supporters, a group that includes the large nonprofit United Way, the Reese-Davidson Community represents a moral tour de force — an example of modern architecture being utilized to address the area’s homelessness crisis where it’s most acute.

With recent estimates of as many as 1,600 people living in tents and cars in Venice — among the highest concentrations in L.A. County — the neighborhood has lately emerged as a major flash point in the area’s larger debate over homeless housing. That debate reached a fever pitch in late summer, when Alex Villanueva, the bombastic county sheriff, initiated a series of controversial sweeps of the large tent encampments that had been crowding the beach and boardwalk.

Sonya Reese Greenland (Youtube via Safe Costal Development)

As the larger debate continues, City Councilman Mike Bonin, who represents Venice, has also emerged as perhaps L.A.’s most forceful advocate for homelessness rights, even revealing that at one point he was living on the streets himself.

“I can’t tell you how much turmoil there is in your heart when the sun is setting, and you don’t know where you can sleep,” Bonin said this summer, explaining his vote against a new city anti-camping ordinance.

Other homeless housing projects have also gone up in Venice, but opponents of the Reese-Davidson Community, led by a neighborhood group called Fight Back, Venice!, have homed in on that development as an egregious example of governmental waste and failed planning.

The group refers to the project as “the monster on the Venice canals” and raises objections based on everything from the building’s size and cost to its susceptibility to sea level rise. Opponents argue that the construction would take away beach parking from ordinary residents, do little to address the homelessness crisis and dramatically impact the longstanding character of the Venice Canals neighborhood — pointing especially to the contemporary-style building’s “Texas doughnut” element, whereby residences are wrapped around a vertical parking garage.

“The site is just so fundamentally unsuitable for development,” Chris Wrede, a founder of the group, said earlier this year. “I think it’s disastrous for Venice.”

The city’s planning commission approved the project in April, although it still needs full approval from the City Council. A recently scheduled Planning and Land Use Management committee hearing was postponed until December.