For 40 years, Louis Rosemond lived in Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood, feeling like he was in his native Port-au-Prince. “We have the same restaurants as in Haiti, the same barbershops, the same rara,” said the 64-year-old artist, referring to the Haitian street festival music. “Little Haiti is Haiti.”

Yet all that is changing. The neighborhood has caught the eye of developers, pushing up property values and leading owners of older housing to sell to the highest bidders or demolish buildings to make way for new projects, as Rosemond’s landlord did.

Similarly, south of Little Haiti, MacKenzie Marcelin enjoyed living in Miami’s Allapattah neighborhood, although the nearby construction of a shopping center with luxury rental towers loomed like an omen. Allapattah rents have been rising, and Marcelin could not afford a $300 hike when it was time to renew his lease. “We got priced out,” said Marcelin, a community organizer who lives with his girlfriend.

Little Haiti and Allapattah, long economically lagging and largely minority neighborhoods, are being gentrified. As Miami continues to evolve, one factor makes the two areas’ evolution different: They are on some of the highest ground in the city, and are poised to better withstand sea-level rise, storm surges and floods.

Amid the development wave, an outcry has come from housing advocacy groups, calling these areas the epicenter for climate gentrification — a phenomenon at the intersection of Miami’s two nemeses of sea-level rise and housing unaffordability.

Researchers describe climate gentrification as investment that moves from high-risk to low-risk areas; as such neighborhoods become more desirable, rents go up and low-income residents are priced out. Essentially, the low-income residents are pushed to areas more vulnerable to climate risk.

Little Haiti and Allapattah’s advocacy groups and displaced residents say that investors know exactly what they are doing: Rushing to Miami’s highest-elevation neighborhoods to preserve their investment long-term in light of rising sea levels.

Yet developers of some of the biggest projects in high-ground Miami neighborhoods counter that it is the central location, not elevation, that played into their decision. One developer, Anthony Burns of Magic City Innovation District in Little Haiti, said climate gentrification is a talking point for opponents without much research to back it.

The term became mainstream in 2018 when a group of Harvard University researchers released a study that showed Miami-Dade County real estate values in higher-ground areas were growing faster than in low-lying areas, showing that climate change is factoring into consumer preferences.

In fact, whether developers are guided by ground elevation to Little Haiti and Allapattah does not matter, said Zelalem Adefris, co-chair of nonprofit Miami Climate Alliance.

“The outcome is that people are pushed out from neighborhoods that are on higher ground,” she said.

Big tech in Little Haiti

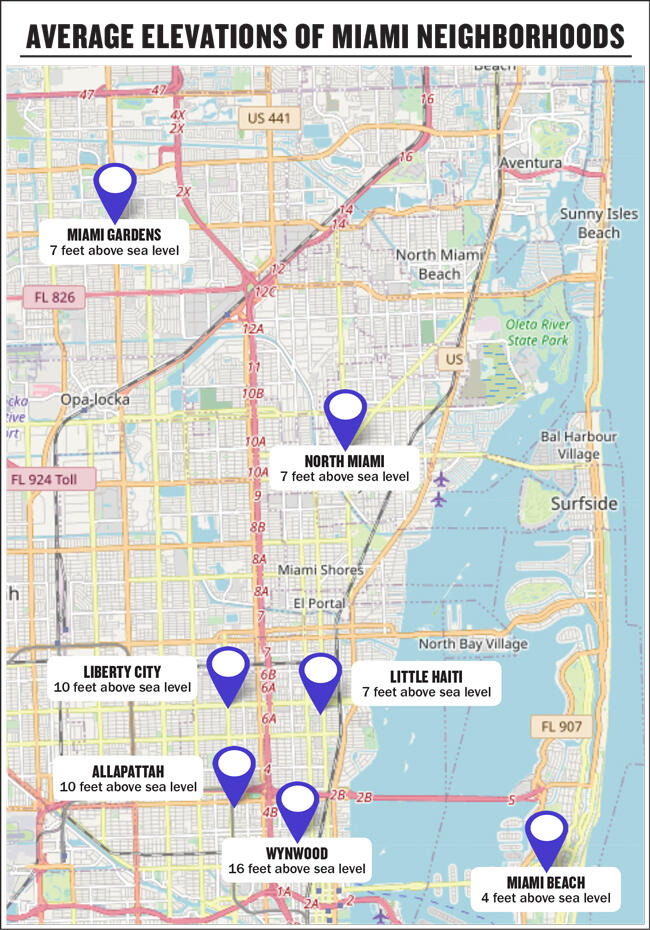

Little Haiti is at about 7 feet above sea level, and Allapattah is at about 10 feet, according to the Worldwide Elevation Finder.

Still, elevations vary from block to block and from lot to lot. A map created at Florida International University to study the impacts of sea-level rise shows parts of Little Haiti at 14.5 feet and parts of Allapattah at 6 feet.

By comparison, parts of the Edgewater neighborhood, a booming condo market in Miami, are as low as 2 to 3 feet above sea level. Across Biscayne Bay, Miami Beach’s southern tip ranges from 5 to 6 feet, according to the FIU map.

Part of the 18-acre Little Haiti assemblage where the massive and controversial Magic City Innovation District will be built exceeds 14 feet in elevation, the map shows.

Construction is to start on the first 25-story apartment tower, with 359 units, in the second half of 2022. In addition to apartments, plans for the 8.5 million-square-foot Magic City call for possibly condos, retail and office space. The offices are expected to be a hub for the techies that Miami Mayor Francis Suarez is courting, said Burns, a Magic City co-developer.

“One of the hallmarks of Silicon Valley is they really look to have density of peer groups. Given the scale of what we have, we will be one of the few places in Miami that allow these tech companies to create this collision-point atmosphere,” said Burns, co-founder and partner at Plaza Equity Partners.

Not far from more recently redeveloped areas like Midtown and Wynwood, Little Haiti is in the line of Miami’s natural growth path. That — and not elevation — was the driver for Magic City, Burns said.

As for the outcry over gentrification, it is based on the incorrect premise that it is all bad, he said. “Neighborhoods are in a constant state of flux. When new projects come in, the conclusion is the tide raises most of the ships. It’s a good thing,” Burns said. “Are there negative things? Yes, of course.”

The $1 billion Magic City project initially was planned to have below-market rentals, but then the developers quietly negotiated with city officials to instead contribute $31 million to a city-managed fund designated for housing and other community benefits. They cut the first $3 million check in March.

Jesse Keenan, one of the Harvard study’s authors, said that academically it is a mistake to point to one neighborhood such as Little Haiti and call it climate gentrification. It usually takes place across sprawling geographic regions and involves the movement of a large population. But as a practical matter, he added, what is happening in Little Haiti is, in fact, climate gentrification, because the neighborhood is on high ground and its residents are being displaced.

Rosemond blames the developers and speculators scooping up housing for pushing him out. He now lives in North Miami Beach and plans to move to Opa-locka.

“Little Haiti is broken,” he said.

Not just about floods

The Harvard study showed that housing values, in particular, appreciated faster in low-risk areas compared with high-risk ones. Coastal areas are considered high-risk.

“It is shaping decisions — and nondecisions to move to the coast,” said Keenan, an associate professor of real estate at Tulane University. “There is a lot of data on that now.”

To turn the tide of housing displacement in Miami, the city in February started a program to buffer “naturally occurring affordable housing” from climate impacts. These properties are not mandated to keep rents low, but have remained attainable as they are smaller and older. So, in a rental market that is going gangbusters this year because of high demand from locals and newcomers, the properties are giving Miami’s low- to mid-income residents a reprieve.

Another rendering of the planned towers at Magic City Innovation District (Arquitectonica)

And while market pressures may push owners of such properties to renovate and create luxury units, the city is trying to limit that, said Jon Klopp, Miami’s coordinator of special projects for dealing with climate change. “We are trying to create an incentive for them to maintain affordable housing,” he noted.

Under the Keep Safe Miami program, owners and operators of buildings with four to 20 units can obtain up to $100,000 in forgivable or deferrable loans to make their properties climate-resilient. More than half of the units have to be rented for up to 80 percent of the area median income, which this year the federal government determined to be $61,000 for Miami-Dade County.

Owners can assess their properties’ climate exposure, and the loans finance improvements. This extends to moving HVAC or electrical equipment from flood areas on the property to higher floors, and because extreme winds and heat are a problem, higher-quality windows also are options, Klopp said.

“The point is to keep the residents there,” Klopp said. “To not have them pushed out by climate change.”

Additional minority neighborhoods that are also on higher ground are closely watching how events pan out in Little Haiti. In Liberty City, west of Little Haiti, the ground elevation is about 10 feet, according to FIU.

“I think Liberty City is going to be entirely dependent on what happens in Allapattah,” Keenan said.

All eyes on Allapattah

Allapattah is better known among locals as Little Santo Doming in recognition of its population largely hailing from the Dominican Republic, although over time the area also has become home to Central Americans, Haitians, Cubans and U.S.-born Blacks.

Recent investment is coming from some of the biggest names in Miami real estate. Moishe Mana has accumulated land and warehouses with no immediate plans for them, opting instead for long-term speculation.

Developer Lissette Calderon is working on her second of three apartment buildings in Allapattah, the Julia, with 323 units. Calderon has finished the 192-unit No. 17 Residences, and next is set to build Allapattah 14, which will have 237 units.

Ultimately, her projects are alleviating climate change, not exacerbating it, Calderon said in a statement. They are in a neighborhood that already has infrastructure, and not on raw, green land that would be paved over. And their proximity to Metrorail stops will reduce carbon emissions that otherwise would come from cars, she added.

In a nod to Allapattah’s open-air produce market, a food distribution hub, developer Robert Wennett named his project the Miami Produce Center. The 1.4 million-square-foot project is planned to include thousands of apartments, including co-living units, perched atop existing warehouses that will be repurposed.

When Keenan was researching a Copenhagen district touted as the prototype of how to buffer neighborhoods against climate change, he found the adaptation was so successful that it attracted new residents.

“It was driving up prices, and it was found in some cases to be driving out the very same people that those investments were meant to protect,” Keenan said.

Allapattah could follow a similar trajectory, as development could prompt investment in resilience. But it also has a shot at making things right, he said: “There is plenty of time to save the day here.” Several big projects on tap can create the momentum necessary to lead to construction of low- to mid-income housing, he said.

“The bottom line is people have to go somewhere,” Keenan said. “And there is an inevitability on some level. So let’s try … to provide for those who don’t have the opportunities, or people who are being left out.”

For Marcelin, it’s too late. He now lives near Miami Gardens in an older building where his balcony has flooded several times during this year’s rainstorms.

Land economics generally dictate that higher-risk areas are just more affordable. In Miami-Dade “it has played out that way pretty consistently,” Keenan said.

“A lot of folks are being pushed up north or down south to areas prone to flooding,” Marcelin said. “That is a very real thing that is happening.”