It was the spring of 2014 when the Related Companies’ president, Bruce Beal, realized he had a façade problem.

Construction was finally booming again after grinding to a halt during the financial crisis. But a scarcity of glass for a new crop of skyscrapers was driving up prices and delaying projects nationwide — including Hunter’s Point South, a 925-unit affordable development where Related and its partners waited several months for a $13 million delivery of windows.

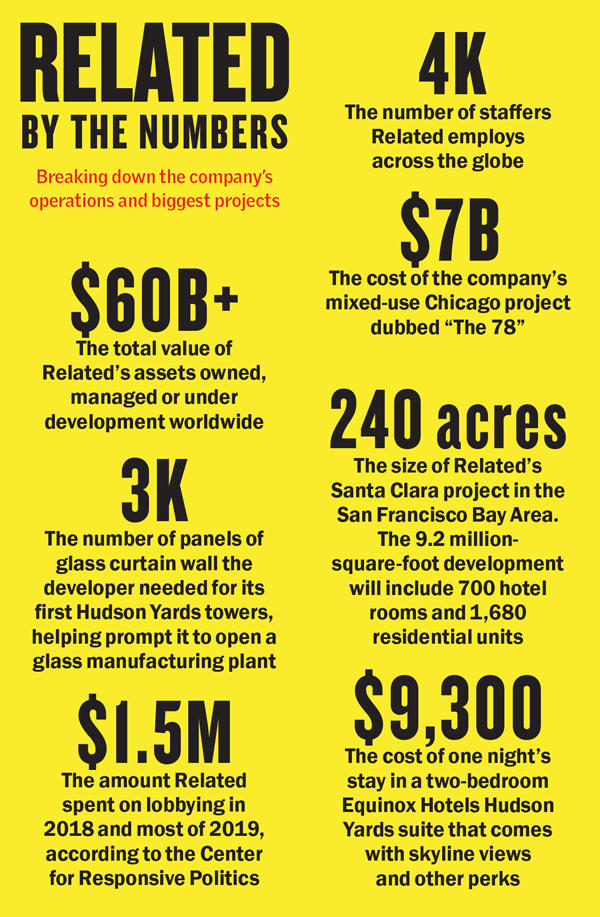

Related also needed at least 3,000 panels of glass curtain wall for the first of 16 planned towers at its Manhattan megaproject, Hudson Yards. So Beal strode into Stephen Ross’ office and convinced the company founder and chair that Related needed to manufacture its own glass.

“If you don’t take the risk, we’re going to be screwed,” Ross told Beal as he was signing off on the pitch.

A year later, Related opened New Hudson Faces, an 180,000-square-foot glass manufacturing plant in Linwood, Pennsylvania, near the Delaware border.

Related didn’t become one of the biggest private developers in the country by waiting for the opportunity to knock. And while Hudson Yards — which officially opened with a star-studded party in March — is the firm’s most visible project, it’s far from the only major development it’s working on.

The company is also building a $7 billion mixed-use Chicago project dubbed “The 78” and a 9.2 million-square-foot development on 240 acres in the San Francisco Bay Area that will include 1,680 residential units and 700 hotel rooms.

Related and its founder were thrust into the national spotlight in August when Ross hosted a ritzy Hamptons fundraiser for President Donald Trump’s re-election. But the public backlash has done little to slow down Related’s big development plans.

Related now employs about 4,000 people globally and has over $60 billion in assets owned, managed or in the works. And even as it’s pouring billions of dollars into development, the company is increasingly diversifying into other cities with a far-flung web of new businesses — from fund management and glass manufacturing to doggy day cares and an exercise chain.

This past summer, Related bought a short-line railroad company in Denver, acquired a stake in an airport rental car company and announced plans to launch a dozen Equinox hotels, having bought the fitness company in 2006. (Related executives are now part of an investor group that owns the chain.)

“Real estate has changed,” Related’s CEO, Jeff Blau, told The Real Deal during a recent interview at Hudson Yards. Since the financial crisis, he said, one-off developments have become more competitive and less lucrative — a harsh reality for some. But Related has found a niche in ultra-complex projects that few rivals will take on as it moves into higher-margin businesses, including hotels and property management.

To date, more than 90 percent of Hudson Yards’ 8.8 million square feet of office space is leased up.

“You can’t just build a physical asset [anymore],” Blau said. “You have to be involved in what happens inside.” The goal is a business that’s “less subjected to market fluctuations,” he added.

That plan will be put to the test as Related embarks on Hudson Yards’ second act in a less-than-perfect market. Phase two will contain 6.2 million square feet, including an expected six residential towers and an elementary school.

But in the decade since the $25 billion megaproject was planned, New York’s hotel industry has suffered from oversupply, retail has been decimated, and the luxury residential market has weakened.

“We all know the high-end condo market is sucking wind right now. That uncertainty makes it pretty difficult to proceed,” New York real estate attorney Joshua Stein said about Hudson Yards’ second phase.

“If those condos are not a solid source of value at the end of the day, it could very well be that the project doesn’t pencil out,” he added.

Hudson yardage

On a brisk day in mid-October, Blau surveyed Related’s massive development on the Far West Side with an iced coffee in hand.

Just 44 when he was named CEO back in 2012, the perpetually youthful executive marked his 50th birthday in April 2018 by running his first marathon. “I used to run down here all the time while we were building this,” he said, sweeping his hand through the air and gesturing toward the six completed towers that make up Hudson Yards’ first phase of development.

In an industry known for sharp elbows, Blau’s seen as the nice guy who shows up to his kid’s hockey practice, to Cycle for Survival events at Equinox and to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority boardroom when it’s time to hash out a deal and Ross is in China. More than a dozen people interviewed described Blau as a consummate dealmaker — the kind of person who clicked with Ross as a student at the University of Michigan and then, two decades later, skillfully assembled the financing for Related’s biggest project yet.

This fall, wearing a dark suit and a snowy dress shirt, the bespectacled Blau could be mistaken for any one of the bankers or lawyers he’s lured to Hudson Yards, including those at Wells Fargo, KKR and SAC Capital, to name a few. It would be another month before Facebook signed a 1.5 million-square-foot lease across three towers at the project.

Related’s Jeff Blau

Although Related was once betting on retail and residential development to carry Hudson Yards, Blau said that as those sectors have softened, the project’s strong office portion has been a surprise “game changer.”

So far, 91 percent of the 8.8 million square feet of office space has been leased up. Blau said Related zeroed in on the struggle companies are having to attract talent and refined its pitch for Hudson Yards as the “workplace of the future,” where employees can live, work, shop and socialize.

Dan Doctoroff — the deputy mayor for economic development under Mayor Michael Bloomberg and a good friend of Ross — said many people doubted whether the West Side could ever be developed. “I say all the time, they were the only developers in the world who could have pulled off Hudson Yards,” said Doctoroff, now the chair and CEO of urban-tech startup Sidewalk Labs, which has office space at 10 Hudson Yards.

But the megaproject was never a sure thing.

Related’s bid for the 28-acre site on the Far West Side fell through in 2008 after News Corp. pulled out as an anchor tenant. When Tishman Speyer — which was selected by the MTA, owner of the site — walked away after the financial crisis hit, however, Related got a call back.

“It was a scary time in the real estate industry,” Blau recalled.

Yet he, Ross and Beal had an ace up their sleeve. In late 2007, an investor group including Goldman Sachs, Michael Dell’s MSD Capital, Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Development and the Olayan Group provided Related with $1.4 billion in debt and equity. The deal gave the group a 7.5 percent ownership stake in the firm.

“I can’t tell you how much it helped them get through a bad period,” said Marty Burger, president of Silverstein Properties, who worked at Related in the early 1990s and again from 1997 to 2006. “It gave them additional connections throughout the Middle East,” he added.

To date, one of Related’s singular feats has been raising $17 billion in debt and equity for Hudson Yards from an array of international investors. As recently as November, it secured a $1.25 billion loan from Wells Fargo, Deutsche Bank and Morgan Stanley using 55 Hudson Yards as collateral.

“They found capital in every single part of the world,” said Matt Borstein, global head of commercial real estate at Deutsche Bank, a longtime Related lender that provided $4.5 billion in financing for Hudson Yards. Borstein said that when Ross and Blau pitched the bank on Hudson Yards, they meticulously laid out their vision for a new neighborhood that would be an economic engine unto itself.

Blau in particular, Borstein said, urged the lender to think of Hudson Yards not just as a collection of buildings but a city within a city, and the financing not just as a loan but a “bridge to billions of dollars in more loans.”

Controversy calling

For those who had somehow managed to remain in the dark about Related, that changed this summer when Ross’ decision to host the Trump fundraiser dominated cable news.

Trump critics canceled memberships in Equinox and its subsidiary SoulCycle even as the brands tried to distance themselves from the fracas. Despite calls for Ross — who has been friends with Trump for decades — to cancel, he didn’t.

As a means of deflecting criticism, Equinox CEO Harvey Spevak ultimately donated $1 million to a slew of charities, from LGBT groups to cancer research, and David Chang’s Momofuku donated all of its profits earned on the day of the fundraiser to groups including Planned Parenthood, the Sierra Club and Everytown for Gun Safety.

Jorge Perez, chair and CEO of Related Group in Miami, defended the company and said the backlash was “blown out of proportion.” In America, people should have the “absolute right” to back any candidate they choose, said Perez, a liberal Democrat and outspoken Trump critic. Within a few months, the controversy had tapered off with few casualties, other than the spate of bad press, but for many progressives, the fundraiser was another sign of Related flexing its political muscle.

Stephen Ross’ August fundraiser for Donald Trump in the Hamptons sparked a public outcry that has since died down.

Last year, the developer became embroiled in a bruising fight with Gary LaBarbera and his Building and Construction Trades Council, which represents dozens of metro-area construction unions, over Related’s use of nonunion labor at Hudson Yards.

The brawl started when the unions refused to work on Related jobs; things escalated when Related fired off two lawsuits accusing the BCTC of inflating costs by $100 million at the project. BCTC responded with daily picket lines at Hudson Yards and raucous rallies at Columbus Circle and Times Square. The two sides called a truce about a week before Related’s grand opening for the shops at Hudson Yards.

After all the mudslinging, Beal maintained that challenging the unions was “the smartest thing we ever did.” Certain investors “tried to threaten us,” he said, but Related held its ground.

“It wasn’t about winning or losing, it was one of the best things for the city,” he argued. “At the end of the day, we stuck up for ourselves.”

But the battle with Related struck a nerve among union stalwarts, who viewed their fight with the development juggernaut as a referendum on their influence going forward, according to other sources. “This was a very, very important fight,” said Joshua Freeman, a professor at Queens College and the Graduate Center at CUNY. “It’s setting benchmarks and norms for the industry.”

By virtue of its size, Related has set the agenda for development before — for better or worse.

In 2018 and 2019, Related spent $1.52 million on lobbying, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, which tracks political donations at the federal level. One key issue is EB-5 — the controversial program that gives foreigners a green card if they invest $500,000 in distressed areas.

Thanks to creative gerrymandering, Hudson Yards qualified to receive EB-5 funds due to its location in an area that extends up Manhattan’s West Side to Harlem. And Related — which has raised $1.6 billion in EB-5 money for Hudson Yards — has fought hard to stave off changes championed by Sen. Chuck Grassley, an Iowa Republican and an outspoken critic of the program.

The official opening of Hudson Yards in March, however, underscored critics’ concern that Related was pouring money meant for underserved areas into a playground for the rich, with luxury condos, high-end shops and shiny new offices that will house major corporations and hedge funds.

Architecture critics have panned Hudson Yards — calling it fortress-like and inauthentic. “It is, at heart, a supersized suburban-style office park, with a shopping mall and a quasi-gated condo community targeted at the 0.1 percent,” Michael Kimmelman wrote in the New York Times last year. That criticism struck a nerve among the wave of left-leaning politicians (and their supporters) who have challenged corporate greed.

A month after Amazon abruptly pulled the plug on plans for a Long Island City campus amid harsh criticism of its $3 billion in government incentives, economists at the New School published a report revealing that Hudson Yards benefited from double that amount — nearly $6 billion — in tax breaks and other government assistance.

“It’s one thing for a private developer to do that on their own dime,” said James Parrott, senior director of fiscal and economic policy at the New School. “It’s another thing for taxpayers to subsidize it.”

RXR’s Seth Pinsky, who was president of New York City’s Economic Development Corporation when Related was awarded the redevelopment of the railyards, defended the incentives. Pinsky said that when Hudson Yards was planned, the neighborhood had little development potential and had seen several false starts (including a failed bid for the Olympics).

“To induce private developers to put billions of dollars at risk on new development in the area,” he wrote in an email, “it was absolutely necessary for the city to agree not to collect certain future taxes.”

Doctoroff recalled Related’s early bet on the High Line in 2005, at a time when the city needed buy-ins from 38 landowners who wanted the old elevated rail line to be demolished. Instead, elected officials proposed a rezoning that would allow owners to sell the air rights above their buildings to developers throughout West Chelsea, but there was a question about whether there’d be a market for those air rights.

“Jeff Blau stood up in the meeting when the High Line property owners questioned whether or not the air rights would be worth anything,” Doctoroff recalled. “And he said, ‘We’re buying.’ That swayed everybody.”

Joint efforts

Related didn’t become a powerhouse overnight.

In 1972, when Ross founded Related with $10,000 from his mother, the company was an affordable housing developer first and foremost. By the end of the decade, Related had built 5,000 affordable units, and over the 1980s and 1990s it expanded into market-rate housing, office and retail.

A turning point came in 1998, when Related won the right to develop the Time Warner Center — its first large-scale, mixed-use project.

Burger said his former boss has an insatiable appetite for bigger and more complex projects.

“There’s this philosophy,” he said. “[Since] it takes the same brain damage to do a $100 million deal — you might as well do a $1 billion deal.”

Today, Related is a buttoned-up place where expectations run high.

“Sloppy dress communicates sloppy thinking,” a former employee said of its corporate mentality, including its suit-and-tie dress code. “The attitude most people have there is, ‘We’re not messing around.’” The ex-staffer also described an upwardly mobile culture within Related where talent rises to the top. “If you’re working hard, they will reward you. It’s very competitive.”

Cushman & Wakefield’s Doug Harmon said Related could be used as a Harvard case study for how to run a business. “Ross has always encouraged the strength of the organization” by involving Blau, Beal and COO Kenneth Wong in strategic decisions, Harmon added.

But the shared leadership at Related is something the press doesn’t like to write about, argued Beal, who oversees daily operations, while Ross is known as the visionary and Blau as the dealmaker who lines up investors.

“They want to make it about one person,” Beal said. “It’s hard — even in sports for people to write about the Team. They want to write about LeBron James or Big Papi or Eli Manning.”

In reality, executives throughout the organization are given the runway to execute their ideas.

Outside of New York, the development firm operates under several banners (in addition to Related Cos.): Related Midwest; Related California; and Related Beal, which was formed in 2013 when Related bought the Beal Companies, a Boston-based firm owned by Beal’s family. It also owns a minority stake in Miami-based Related Group, and it partnered with two local operators to form London-based Argent Related and Gulf Related, based in Abu Dhabi.

“If we had an org chart,” a Related spokesperson told TRD in September, “it would be a foot tall and 20 feet wide.”

On the whole, as Related’s appetite for bigger projects has grown, so has its interest in new lines of business. Since its purchase of Equinox Fitness, it has launched Dog City, a pet spa and day care chain, and acquired a stake in CORE, a residential brokerage firm.

“They’re both incredibly opportunistic in terms of making money and not letting things stand in their way,” said Neil Shapiro, a partner at the law firm Herrick Feinstein, which has represented Related. “If it’s a good investment and it fits, they do it.”

Related Group’s Perez — who partnered with Ross in the 1970s after the two competed for a Miami project — said the divisions are all run separately. “They don’t put money into the deals we do,” said Perez, who’s currently overseeing 70 projects. “New York handles New York, and we handle Florida.”

But according to Blau, each of Related’s investments ties back to real estate — even if indirectly.

For example, it backed the company behind Citi Bike to improve how people get around the city. Likewise, it’s partnering with Uber to build a “skyport” for Uber Elevate, the startup’s planned aerial ride-sharing program, at Related’s Santa Clara, California, development.

“We strive for complicated things that others can’t execute on, so if there’s a consistent theme, it’s that,” Blau noted.

In good times and bad

Related’s increasingly diverse portfolio is also a hedge against an economy that’s heading for a correction after a record bull run.

“Anyone can be successful in good times,” said Blau, who joined Related in 1990, only to see the bottom fall out of the economy. “Some of the best deals in history are made during bad times because people are scared and there’s pressure. People say, ‘Why waste a great recession?’ That stuff, I think, is really true.”

Over the years, Blau has taken his own advice.

In 2009, at the height of the financial crisis, Related launched a fund management business targeting underperforming assets. Headed by Goldman Sachs alum Justin Metz, that arm has raised more than $6 billion to date. And with more than 50 borrowers, it has diversified beyond distressed deals alone. Related now originates and acquires debt and invests in multifamily projects, though it is not in the business of predatory lending, Blau stressed. “We’re in the business of providing debt and getting repaid,” he said.

Among its borrowers is Houston-based DC Partners, which secured two loans from Related — a $70 million loan to build a 66-unit condo in San Antonio and another for $140 million, which Related issued in partnership with Bank OZK, to fund a retail pavilion and office tower in Houston.

“Development is very much cycle-dependent,” said Brian Sedrish, a former Deutsche Bank executive who runs Related’s credit business. “When times are slow, you want to take advantage of your expertise, but you want to deploy [capital] in other ways.”

Although Related could ramp up its lending if the economy turns, Sedrish said that time hasn’t yet arrived. “We’ve been very focused on taking our foot off the gas and waiting for more clarity on the opportunities before investing,” he said.

In the meantime, the fund management division has forged ahead with bets on businesses like infrastructure and hospitality — areas where Sedrish said executives felt they could add value by drawing on expertise in operations, development and design. “The benefit is the ecosystem that Related brings in with all its disciplines,” he said.

For example, Related’s plans to develop 12 Equinox-branded hotels would be a “huge part” of the company’s business going forward, Blau said. Through the hotel business, the developer will also enter new markets, such as Seattle, Chicago and Houston, that Blau said are growing faster than core markets. “This is actually the biggest change in the hotel industry, maybe since the W,” he said, referring to how the luxury hospitality brand popularized personalized hotel stays.

Industry observers said the foray is coming at a good time — when national hotel chains are struggling to compete with boutique offerings. Even without Equinox’s loyal members, who will likely patronize the hotels, travelers will be apt to stay at a hotel they associate with fitness and health, said hospitality consultant Bjorn Hanson. “There’s a halo effect,” he added. “It plays into people’s aspirations when they travel.”

Political headwinds

But even the most successful firms run up against intractable forces.

For Hudson Yards’ second phase — which Related filed plans for in 2018 — those forces are Trump and Chuck Schumer. The president and U.S. senator from New York have clashed over how to fund the $30 billion Gateway Project, which would build a new railroad tunnel between New Jersey and Manhattan. The proposed tunnel would run under the second phase of Hudson Yards, which was to be completed by 2024.

But in late December, the New York Times reported that Related was no longer providing a timetable for completion. If it weren’t for that funding disagreement, the developer would be ready to break ground.

“That will delay this, definitely,” Blau told TRD during the October tour of Hudson Yards, arguing that the tunnel is “for the greater good of the city.”

“It’s pretty frustrating,” he said.

Of course, there’s little public sympathy these days for megadevelopers — even if the delay ends up costing Related millions of dollars or more. Sitting in an empty room adjacent to Electric Lemon, the restaurant at the new Equinox Hotel, Blau maintained that real estate and other business interests have “gotten a bad rap” in today’s political climate.

“It’s killing me how left these candidates have to go to get through the primaries,” he said — stopping short of mentioning Trump. “Capitalism is part of the success we’ve had here,” he said. “I think we’re heading in the wrong direction if that’s where [the country] goes.”

Blau also predicted that the overhaul of New York’s rent law would backfire, though he stood by Related’s mission to create more affordable housing.

“We do it because it’s the right thing to do, and we do it because if you’re building projects on this scale, if cities aren’t working, then the developments can’t work,” Blau said.

Related is the fifth largest multifamily landlord in New York City, according to a recent TRD analysis of data from the Department of Housing Preservation and Development.

But the company, which owns more than 10,000 affordable apartments in the city, was less impacted by the state’s new rent law than some other major landlords — including Blackstone Group — due to its long-term investment strategy. Blau said that as a matter of policy, Related does not look to flip its units to market-rate.

But that doesn’t mean the developer intends to leave cash on the table.

“You don’t build one of the most successful real estate companies in the world by not making money,” Doctoroff said.