As residents continue to pour into the coastal cities of Jersey City and Hoboken, corporations seem to be headed in the opposite direction: inland.

Though it flies in the face of the urbanization of the region, with major developers like Mack-Cali investing in waterfront offices and residences, some major business tenants are putting down stakes smack dab in the middle of the suburbs and other locations relatively far from the Gold Coast.

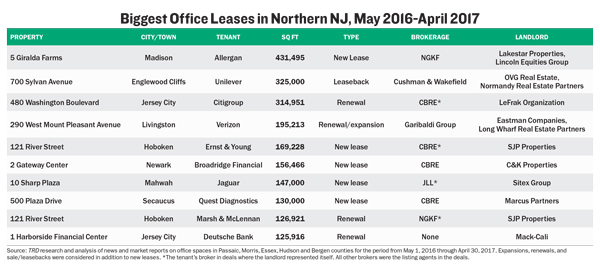

Of the 10 largest office deals in the last year, according to an analysis by The Real Deal, six took place somewhere other than Hoboken or Jersey City, two reliably popular corporate addresses. Based on reporting and market reports of deals, TRD’s ranking of the biggest leases tracked transactions that took place between May 1, 2016 and April 30, 2017 in Bergen, Essex, Hudson, Morris and Passaic counties and considered new leases as well as renewals and expansions, ranking them by square footage.

While some deals on the list confirmed a steady investment in the coastline — Ernst & Young, at No. 5, moved into 169,228 square feet at Waterfront Corporate Center in Hoboken — many others opted for the suburbs, like pharmaceutical giant Allergan, which signed a new lease for 431,495 square feet in Madison in the top deal of the year.

Why resist the hot markets of Jersey City and Hoboken? Those water views are just too expensive, brokers say.

“You can only push pricing so far,” said Christopher Marx, a senior vice president with Savills Studley, who echoed other agents. “Once you get pricing that starts to get comparable to Downtown Manhattan, you’re going to lose tenants.”

Annual office rents average $33 a square foot on the waterfront, according to CBRE. Further inland in Morris County, office rents average $30 a square foot, said Joel Bergstein, president of Lincoln Equities Group, which co-owns the new Allergan offices with Lakestar Properties.

In mid-May, on the waterfront between the Lincoln Tunnel and Paulus Hook in Jersey City, there were 12 office spaces with more than 100,000 square feet available for lease, Marx said. That number is high, he said, adding that in a healthier market, there would be just three or four offices of that size available.

The vacancy rate across Northern New Jersey was at 22 percent in the first quarter of 2017. Many brokers and developers say it would be far worse if not for the Grow NJ state assistance program, which heaps generous tax credits on companies that choose to locate, or relocate, in New Jersey. But the future of the New Jersey Economic Development Authority’s program is uncertain, as it’s due to sunset in 2019. Gov. Chris Christie’s successor will likely determine its fate after the 2018 election.

“Those incentives play a big role in decision-making,” said David Stifelman, a managing director of JLL who represented Jaguar Land Rover North America in its lease of a 147,000-square-foot facility on Route 17 in suburban Mahwah, the seventh-biggest lease in TRD’s rankings. The company, which was considering leaving the state, he said, received $28 million in tax breaks over a 10-year span.

Broadridge Financial Solutions considered Weehawken and Ridgefield Park when its lease was up in Jersey City’s 2 Journal Square, ultimately landing in Newark in the sixth-largest deal in TRD’s ranking. The company will receive $23 million in credits over a decade for the move. The financial technology company, an offshoot of Automatic Data Processing, took 156,466 square feet at 2 Gateway Center on Market Street, a 1970s 18-story tower renovated in 2015 by owner C&K Properties. Broadridge’s 15-year lease is for a space vacated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. The average annual rent in Newark is $28 per square foot, according to CBRE.

“We did an exhaustive search,” said Michael Ciotta, a director at Oxford and Simpson, the agent who represented Broadridge in the deal. Newark “is such a strong location, considering the company’s long-term growth plan.”

But some companies have no use for an urban environment. Jaguar Land Rover kept its headquarters in the suburbs, moving from one location in Mahwah to another in the same town, in part because its employees own homes there, Stifelman said. Installing a company in Jersey City might allow better access to a millennial workforce, but that kind of staff isn’t a priority for an established automaker.

“It would have been way too costly and too disruptive to relocate,” he said. “We thought, ‘Let’s try to make this move as easy as possible.’”

The biopharma industry relies on a similar kind of workforce to that of Jaguar Land Rover, which might explain why so many of its companies continue to seek out suburban addresses. Allergan inked its 13-year lease for the entire building at 5 Giralda Farms, a business-park property that Pfizer owned until 2013. Actavis bought Allergan in 2015, then shed some of Allergan’s former, scattered locations, prompting the need for a new headquarters.

State aid gave Allergan an incentive to stay in New Jersey, as the company won $58 million in tax credits in a 10-year deal.

But it had another major incentive to move: The property’s co-landlords, Lakestar Properties and Lincoln Equities Group, offered to build a $9 million parking garage and threw in a $52 million renovation bonus, said Bergstein of Lincoln Equities. Allergan’s massive buildout will include a new HVAC system, roofing and Wi-Fi in addition to the refurbishment of the property’s gym and basketball court. “The bones of the building permitted them to do the kind of renovation they were looking for,” Bergstein said.

Because the average age of office buildings in New Jersey is an old 37, according to CBRE estimates, landlords might have to overhaul their properties in order to continue to attract new tenants. “To be successful as a suburban developer, you have to invest,” Marx said.

Similarly, Mack-Cali, the state’s largest office landlord, is adding a Wegmans grocery and 24 Hour Fitness gym inside a new structure at its 600-acre, a sprawling office park in Parsippany, where average annual rents are $25 per square foot, according to CBRE.

While Mack-Cali recently sold off a large portion of its suburban office holdings (see related story), other developers won’t necessarily follow suit. Some customers will always prefer suburban sprawl.

“All the buzz might be about companies being in urban environments,” said Bergstein of Lincoln Equities. “But others are looking at the cities and saying, ‘Forget about it.”

—Harunobu Coryne provided research for this article