In 2009, Forest City Ratner stunned the city and fired starchitect Frank Gehry, whose vision for the Barclays Center in Brooklyn had ballooned to $1 billion.

The developer, looking to cut costs at its controversial Atlantic Yards project, tapped Ellerbe Becket, an architecture firm known more for its cookie-cutter venues than its creative vision. But the move blew up in the developer’s face when the new design was widely panned as drab and generic.

With all eyes on the site — which has since been rebranded as Pacific Park — Bruce Ratner made one last change-up: He brought on a then-virtually unknown firm, SHoP Architects, to clean up the mess and come up with a compromise design that was both acceptable and inspirational for the borough’s most high-profile project.

In doing so, Ratner — who was reportedly acting on the advice of another starchitect, David Childs — launched SHoP onto a trajectory that’s continued at full speed.

But at the time, SHoP had only a few relatively small projects to its name, including a 10-story condo in the Meatpacking District, a Hoboken condo conversion and a carousel project. All that changed after it landed the Barclays Center commission.

In 2013, after the controversial Brooklyn arena was completed, developer Michael Stern called SHoP out of the blue to set up a meeting. The partners spent three hours talking to Stern in their office and another three the next day touring the under-construction Walker Tower that his firm, JDS Development, was working on. When the SHoP team asked Stern why he initiated the meetings, the developer said he “wanted to meet the lunatics” who designed Barclays.

“I loved the design, and I thought it took a lot of balls,” Stern told The Real Deal, using a description he often employs to describe the arena, which is covered in thousands of pieces of rusty weathered steel. “That was a very bold design on a project that was watched and political.”

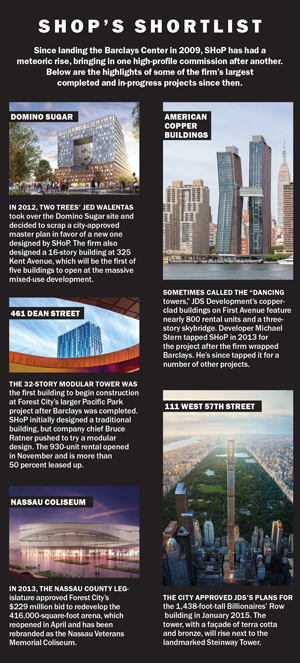

A few days after they met, Stern asked SHoP to design 626 First Avenue, the pair of copper-clad towers known as the American Copper Buildings.

From there, the commissions kept rolling in.

Over the last decade, SHoP has become one of the city’s most prolific architecture firms, having completed 30 projects, with another 19 under construction and 25 in the design phase. Its projects include Stern’s supertall Billionaires’ Row 111 West 57th Street; Two Trees’ giant Domino Sugar redevelopment; Pier 17 at the South Street Seaport; Stern’s 9 DeKalb Avenue, which is expected to be Brooklyn’s tallest tower; and the Staten Island retail complex dubbed the Empire Outlets, among others.

“They grew pretty quickly. They got a lot of assignments,” Forest City Ratner CEO MaryAnne Gilmartin said. “Every time you turn around, SHoP is designing another building. When we found them, they were still a hidden secret.”

Not only is the firm knee-deep in commissions, but it’s also been busy redefining the architect’s role, getting involved in the business end of its projects by periodically investing in them. And the company has also carved out a niche using high-tech digital software to design and manufacture materials.

All this success isn’t to say that SHoP hasn’t hit roadblocks: During the last recession, it was forced to dramatically contract its staff, and a few of its projects haven’t panned out as planned.

In addition, like all architecture firms, SHoP now faces a softening market. “Clients are careful with their and other people’s money,” said Reed Kroloff, former editor of Architecture magazine and a design consultant, who was speaking generally but has followed SHoP’s rise. “They want to protect their investments.”

No ‘napkin’ designs

The five partners who founded SHoP — the husband-and-wife duo of William and Coren Sharples; Bill’s twin brother, Chris Sharples; and another husband-and-wife team, Gregg Pasquarelli and Kimberly Holden — met at Columbia University’s architecture program in the early 1990s.

They arrived with very different backgrounds (finance, fine arts, art history and political science), a part of the firm’s origin story that the partners like to tout as the foundation of their multidisciplinary practice. After graduation, the five classmates collaborated on a few projects, first as Sharples Design. In 1996, they opened their first New York City office in a Murray Hill co-op before officially launching under the name SHoP in 1999

Their early commissions included the abovementioned carousel house in Greenport, Long Island, the Hoboken condo and a pedestrian bridge on Rector Street in Lower Manhattan.

Even back then the firm was on the cutting edge when it came to using technology. For the carousel house, the firm 3D-modeled, and then fabricated, stainless steel sex bolts to elevate the structure, an unusual step for an architecture firm at the time. In the late 1990s, Architecture magazine commissioned the firm to design a 10-foot-high booth for a trade show that consisted of laser-cut titanium sheets, folded into nearly 500 different shapes.

“People were coming to this booth just so they could lay hands on it,” Kroloff said. “It was like some sort of visit to a religious shrine.”

The Meatpacking District warehouse-to-condo conversion, known as the Porter House, was one of the firm’s first major New York projects. In some ways, the 22-unit project, which was completed in 2003, was a natural sequel to the trade-show booth — in the sense that its façade featured custom-made zinc panels. But it was also a giant leap for the firm in terms of scale.

“It’s very unusual for a firm of their age to be given the size and complexity of projects that they got when they got them,” said Kroloff. “They’d done a park, a merry-go-round, and then someone handed them a 10-story building.”

Despite having 200 staffers now and a far heftier book of commissions, the firm still maintains a startup vibe. Its office in the Woolworth Building has a billiards table, a bar, aircraft-themed conference rooms and renderings tacked to the walls picturing dinosaurs roaming among humans in a playful display of scale.

Yet despite the firm’s growth and higher profile, it still doesn’t operate like its starchitect counterparts. “When you work with a great architect, who is a personality, it’s a whole thing,” Gilmartin said.

Rather than relying on “what one person draws on a napkin,” she said, SHoP has a far more collaborative process.

Still, in many ways the firm has no distinct style. The partners seem to cherish this amorphous identity.

While that generalist approach has helped it rack up a wide variety of projects, it can be a drawback when competing against firms that have a strong track record in one market sector. “It does enable them to take on a broader range of work, but it’s also harder for them to argue against the specialty firm,” Kroloff said. “They have to argue that they bring something beyond that expertise.”

Cultivating clients

Since completing Barclays, SHoP has cultivated a few major repeat customers, namely Stern’s JDS and Forest City Ratner.

JDS has now hired the firm for four major projects: 111 West 57th, 9 DeKalb, American Copper Towers and 247 Cherry Street, a 77-story rental building planned for the Lower East Side.

Stern said he shares SHoP’s lack of attachment to one architecture style and likes that the firm is willing to mix modern and traditional materials — like copper, terra cotta and bronze — that have been cut and fabricated using computer-aided design software.

At the Copper Towers, Stern and SHoP wanted to do something other than a “tall glass box,” Stern said. The architecture firm suggested using 4.9 million pounds of copper.

“They are building geeks in the best sense of the word,” Stern said. “We thought they were crazy at first, but our team found a way to get it done.”

Meanwhile, in addition to Barclays, Forest City tapped the firm to design the now-complete Pacific Park modular rental at 461 Dean Street as well as the $165 million renovation of the 416,000-square-foot Nassau Coliseum arena on Long Island.

Gilmartin said she also recently asked SHoP to tackle a six-story office building on Cornell Tech’s new Roosevelt Island campus, but SHoP declined, citing its workload and current project mix.

“I was annoyed, but I was also impressed that they could resist the temptation to please the client,” she said.

On the whole, SHoP’s co-developer relationship with some of its clients has been a bit unorthodox. Pasquarelli said investing in Porter House and 290 Mulberry Street gave SHoP more design freedom.

“It opened up territories for us to innovate because our clients saw us as partners. And that’s really what’s been the most fruitful result of those unusual partnerships,” he said.

“Had we not been partners, I don’t think most other clients would’ve taken that risk,” he added. “They would’ve wanted to go with just the traditional façade manufacturer.”

Pasquarelli and Holden also bought a condo at Porter House in 2006 for $1.3 million, which they sold in March for $3.2 million, according to property records.

The partners declined to name other projects that the firm has invested in, though sources say it has taken smaller stakes in some JDS ventures.

For her part, Gilmartin said she just hopes that despite its growth, the firm maintains its scrappy boutique vibe. “Their only obstacle is their own growth,” she said.

Taking the heat

The firm has had its share of setbacks.

It launched a division called SHoP Construction, but it was short-lived and was folded into the main firm in 2014.

The fi rm’s Woolworth Building office has a startup feel with a billiards table and bar.

Then in 2015, it lost a high-profile partner — Vishaan Chakrabarti — who left to start his own firm. And the next year, after much fanfare, plans for what would’ve been the city’s tallest wooden condo were nixed because of a clash between owners.

Chris Sharples noted that SHoP is keeping that technology “on the front burner,” but said he couldn’t yet elaborate on where the firm would use it next.

And the modular building at Pacific Park was initially billed as a catalyst for more prefabricated buildings, but its innovation has been overshadowed by delays and litigation between Forest City and its former partner, Skanska. It is, however, already more than 50 percent leased up.

In 2013, architecture critic Paul Goldberger praised SHoP for approaching the Domino Sugar site — which it took over from starchitect Rafael Viñoly — with a citywide view in mind.

Two Trees CEO Jed Walentas said he’d been “admiring” SHoP’s work for several years before hiring the firm for Domino. Shortly after buying the 11-acre site in 2012, he toured the property with the firm’s partners, followed by “barbecue and bourbon” in Williamsburg. “It was a good cultural fit from the get-go,” he said.

And it was also a better design fit than Viñoly’s original plan.

“If you’re going to spend a decade working on something, you owe it to yourself to build something you really love,” Walentas said.

Viñoly declined to comment.

Others have been less charmed by SHoP’s designs.

“I go around town, and I see buildings that bend to the right or bend to the left, and they have a sort of clip holding them together, know what I mean? And I wonder what that’s good for,” architect Annabelle Selldorf said of American Copper Buildings during a panel last year. “It doesn’t satisfy me. It doesn’t do anything for people, not just the people that live there, but everybody else.”

Meanwhile, in late 2015, the Howard Hughes Corporation abandoned plans for a 52-story condo/hotel tower at the South Street Seaport designed by SHoP.

Critics argued that the project would be woefully out of place, with Manhattan Borough President Gail Brewer likening it to constructing a tower in Colonial Williamsburg.

And JDS’s planned towers on Cherry Street and on DeKalb in Brooklyn, which are both proposed at 1,000-plus-feet tall, are being criticized for the same reason.

SHoP is, however, no stranger to criticism. Barclays Center came under fierce attacks by critics who came up with a host of creative nicknames, including the Angry Clam and the George Foreman Grill.

But SHoP has taken the heat in stride. “You make 10,000 decisions to make one building, and if you get 99.9 percent of it right, that means there’s 10 mistakes that you’d like to fix,” Pasquarelli said. “But it’s not possible to do that. So you just believe in the ideas, and you learn from each building and you try to get better … And someone’s going to hate it, and that’s cool.”