Just as the market goes in cycles, so too does the legal world that services it. A year ago, New York’s largest real estate law practices were feeling confident — aggressively expanding their ranks, with the dismal days of the crash in the rearview mirror.

Today, those firms are still logging plenty of billable hours and beefing up their staffs, but they are doing so with an eye on a real estate market that is very much in transition.

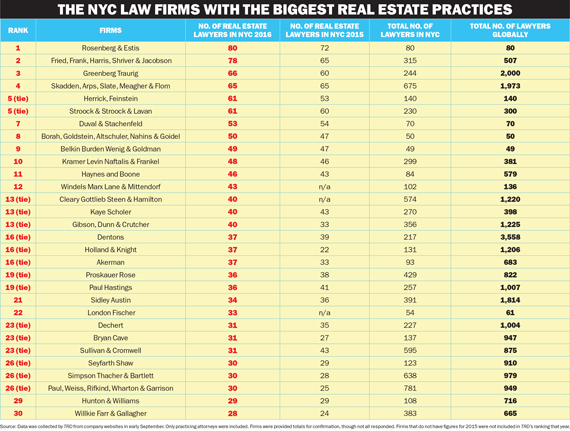

This month, with that holding pattern as a backdrop, The Real Deal ranked the city’s biggest real estate law practices by number of attorneys. The early September snapshot found 1,003 real estate lawyers working at the top 20 firms. That’s up a slight 4.3 percent from 962 last year, and up roughly 32 percent from 761 in 2010.

After several years of handling legal work on blockbuster deals, top Manhattan real estate attorneys say the work they are doing now is beginning to shift. While they are still toiling away on complicated mega developments like Hudson Yards (a project that is likely to continue generating work for lawyers for the rest of this decade, if not longer), as well as large Manhattan buildings sales, there are fewer monster deals now than there were last year. In addition, new cases — largely derived from the drop in construction lending and the new market conditions — are popping up.

“What changes is, you have to chase the work,” said Carl Schwartz, the co-head of Hunton & Williams global real estate practice, who noted that he’s already beginning to see this happen in today’s market.

These market realities have not reshuffled the deck much when it comes to which firms have the biggest New York real estate practices.

The Manhattan-based firm Rosenberg & Estis — which went on a hiring tear between 2010 and 2015 — maintained its position in the No. 1 spot, with 80 attorneys, a net gain of eight from last year. The firm, which only has one office, focuses exclusively on real estate work and handles landlord representation and litigation in addition to services for lenders and others in the real estate business. It was followed by much bigger global players Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson [TRDataCustom] (with 78 real estate lawyers in New York), Greenberg Traurig (with 66), Skadden Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom (with 65), Herrick Feinstein (with 61) and Stroock & Stroock & Lavan (with 61).

In addition, nearly every firm in this year’s Top 10 — with the exception of Duval & Stachenfeld, which slimmed down slightly from 54 lawyers in 2015 to 53 in 2016, and Skadden, which stayed steady at 65 — added attorneys this year. With 13 new lawyers, Fried Frank added more than any of its top rivals.

Nonetheless most firms told TRD that hiring is more methodical and strategic than it was just a year ago.

Evan Levy, head of Skadden’s capital markets practice, said his firm is focused on hiring through a summer associate program and out of law school. And he suggested that the firm is not aggressively expanding at the moment. “We’re at the right size to meet the needs of our clients right now,” he said.

New caseloads

While much has been written about the fact that construction lending has tightened up significantly in Manhattan in the past year, most of the focus has been on what that’s meant for condo projects.

But that shift in the financing world is also opening up a new line of work for the city’s top real estate lawyers who have rosters of developer clients looking to get into the debt game.

Belinda Schwartz, chair of the real estate department at Herrick Feinstein, said the change has not resulted in a workload reduction. In fact, she said the firm, which added eight attorneys since TRD’s 2015 ranking, has added both senior- and junior-level bench strength over the last year. “Institutional lenders are much more conservative [now],” she said. “That’s opened an entire door for not the hard-money lenders, but lenders that play in the middle, between the hard money and the more institutional lenders.”

She said Herrick represented G4 Capital Partners, a “real estate bridge-lending group,” on a number of recent deals, including loans to Michael Stern’s JDS Development Company at two new Brooklyn construction projects — 613 Baltic Street in Park Slope and 71 North 7th Street in Williamsburg.

Carl Schwartz (no relation to Belinda) said he’s also seen clients bringing new types of work to Hunton & Williams — which launched its NYC real estate practice in 2012 and now has 29 real estate attorneys.

Carl Schwartz (no relation to Belinda) said he’s also seen clients bringing new types of work to Hunton & Williams — which launched its NYC real estate practice in 2012 and now has 29 real estate attorneys.

“Everyone wants to find a way to deploy their capital, and since traditional lenders have tightened their belts a little bit and the underwriting is tighter … that creates an opening at a fairly secure place in the capital stack for someone who feels like they can be in a mezzanine position to make an investment like that,” he said.

Schwartz cited World Wide Group and DTH Capital as two major owner/developer clients that are actively seeking debt deals.

“Just this morning, we were talking about how we’re going to have to start using our senior people on more lending deals than on development deals; that’s just the way we see it,” he said. Investors are also tapping lawyers to set up funds so that they can preemptively raise cash to be deployed quickly — key in a market where deals that make financial sense are becoming harder to find.

Nearly every transactional attorney TRD spoke to said they’ve seen an increase in demand for these types of funds. And while structuring the funds is not always a big legal job, the transactions that follow can be.

Herrick Feinstein’s Schwartz said setting up the fund is just the start to a potentially long-term relationship with a client that’s looking to do multiple deals. “If a client is thinking of buying a piece of land, assembling it, getting it rezoned, raising equity through a fund, putting on construction loan debt, doing a condo plan … all those pieces of the deal we can do under one roof,” she said.

The No. 7-ranked firm, Duval & Stachenfeld, is also seeing “a lot of people wanting to do platforms,” said Bruce Stachenfeld, founding partner.

The sponsor, he said, is thinking: “Will I have the money when a deal comes along, or am I going to have to scramble for it? Because if I have to scramble for it, it’s a lot harder to win the deal when someone else already has the money.”

Gary Rosenberg, left, and Warren Estis

One reason developers are looking to set up these funds is that deals have gotten bigger, but the amount of money banks are giving for mortgages has gone down, explained Robert Ivanhoe, the chair of real estate at Greenberg Traurig. That means more equity is required.

“Developers don’t want to put in 40 percent equity and 60 percent financing on a much bigger deal,” said Ivanhoe, who told TRD that his rate is $1,085 an hour (up from $1,050 last year and from $1,025 in 2014). “They don’t have the equity or choose to risk the equity at that level, so if they raise a fund, they can use the fund’s proceeds.”

Greenberg Traurig, which saw a net gain of six real estate attorneys in the past year, has seen firsthand how major players are reacting to market forces. The firm represented the Chetrit Group and Clipper Equity in their $1.4 billion April sale of the Sony Building at 550 Madison Avenue — a deal that’s become emblematic of Manhattan’s softening luxury market. (The developers, who sold to Saudi-based Olayan Group, were planning to convert the 37-story building into luxury condos, with a $150 million penthouse on top, but opted to sell rather than test their luck.)

Jay Neveloff, chair of real estate at the No. 10-ranked Kramer Levin, has seen fund requests coming in, too, but isn’t convinced that it represents a particularly meaningful trend.

“I think all it represents is, developers or entrepreneurs are looking to make sure they have a steady pipeline of equity, and it’s probably more aspirational than realistic,” he said.

More established developers with good track records are more comfortable working on a deal-by-deal basis, Neveloff said, noting that they aren’t as worried about raising capital when they want to do a deal.

Neveloff said, however, that he expects to see more recapitalizations for condo projects already under way, because at many developments, sales are not going as well as originally expected. “They’re going to have to bring in fresh money,” Neveloff said. He said some of his clients are currently waiting by to deploy “rescue capital” to underwater developments.

But it’s not just the transactional attorneys who have real-time insight into the current whims of the real estate market. Litigators also have a front-row seat to what’s happening on the ground. While words like bankruptcy and restructurings are not on litigators’ lips just yet, arbitrations are becoming more common.

“The thing that I’m seeing that I think is indicative of the market is a lot of rent reset arbitration,” said Janice Mac Avoy, the head of the real estate litigation department at Fried Frank.

“The thing that I’m seeing that I think is indicative of the market is a lot of rent reset arbitration,” said Janice Mac Avoy, the head of the real estate litigation department at Fried Frank.

When the market is predictable, Mac Avoy said, landowners and building lessees typically agree on the market value of the real estate underlying a lease, allowing rent adjustments to occur smoothly. But over the past six months, Mac Avoy said, she’s seen an increased number of disputes over rent heading to arbitration. One prominent New York real estate family that owns the ground beneath a 100-plus-unit co-op building near Sutton Place is currently feuding with the co-op board over the market value of the leased land, Mac Avoy said.

“It’s in the beginning, when the market is just beginning to change, that landlords and tenants have very different views of where [the market] is going,” Mac Avoy said.

Ivanhoe said he is also seeing an uptick in arbitrations, which he attributed to the soaring prices of new residential developments.

“Land values, because of condominiums, have risen wildly and out of proportion to the increase in property values,” Ivanhoe said. “Net operating income has gone up, but it hasn’t gone up as much as pure land value.”

The closing table

The past year has seen an impressive roster of deals close. And each of those deals has multiple law firms getting it to the closing table.

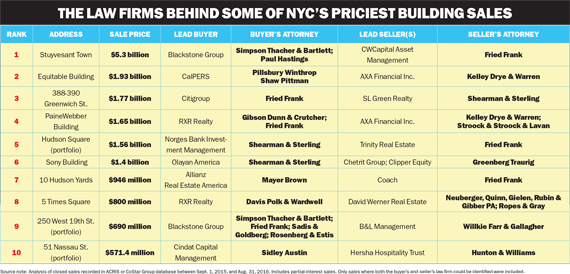

The biggest of those transactions was the $5.3 billion sale of Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village to the Blackstone Group. In that deal, which closed in December 2015, Simpson Thacher & Bartlett (which clocked in with 30 real estate attorneys) and Paul Hastings (which had 36) represented Blackstone. Those two firms have hundreds of attorneys in New York, as well as internationally, but, according to TRD’s analysis, had the 26th- and 19th-largest real estate practices in NYC, respectively. Fried Frank, meanwhile, represented CWCapital Asset Management, the seller in the Stuy-Town deal.

Belinda Schwartz

Those firms were just two on a TRD ranking of the priciest NYC transactions and the law firms that work on them. Other top deals included the $1.93 billion sale of the Equitable Building at 787 Seventh Avenue, which Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman and Kelley Drye & Warren both worked on, as well as the $1.77 billion sale of 388-390 Greenwich Street, which both Fried Frank and Shearman & Sterling handled.

Meanwhile, Fried Frank also represented Coach in the sale of its stake in 10 Hudson Yards to Allianz Real Estate America in a deal valued at $946 million. Along with Gibson Dunn & Crutcher, Fried Frank also represented Scott Rechler’s RXR Realty in its $1.65 billion purchase of the PaineWebber Building at 1285 Sixth Avenue. But while the top trades on this year’s ranking seem just as impressive as the deals that made TRD’s ranking last year, a closer look reveals a more nuisanced landscape. That’s because many of the deals on this year’s list actually closed in 2015, which was a banner year for investment sales in New York, with more than $70 billion in building trades.

So far this year, there are fewer deals on par with last year’s record-setting mega-sales, Ivanhoe said. “While there’s still occasional superlarge deals — $1 billion-plus — I think those have really tapered down,” he said.

Tapping new talent

In NYC’s brokerage world, poaching has been so aggressive lately that it’s led to a number of lawsuits. While recruiting can be cutthroat in the legal world, and lawyers regularly lateral between firms, it’s often the lure of leaving firm life that pulls away attorneys — at least from the top firms.

Fried Frank real estate department chairman Jon Mechanic said he’s more likely to lose a lawyer to a client looking for in-house counsel than to a rival. He cited recent losses to Blackstone and JPMorgan Chase. Herrick Feinstein’s Schwartz, meanwhile, said she lost an attorney to client Lightstone Group. But, not surprisingly, there is far more attorney churn today than in past decades, when many were steadfast in their company loyalty.

“When I started [at Fried Frank] 29 years ago, almost everyone was a lifer,” Mac Avoy said, “but there has become a much greater degree of fluidity … we have a lot more laterals now than we ever have.” Another attorney, who asked to remain anonymous, said that millennial attorneys were especially capricious. “I think there’s just a different mind-set from students coming out of law school now,” the attorney said. “There’s not this desire to practice in one place or even be a lawyer for the rest of their life. … I think that’s just the nature of the millennials.” According to Stuart Saft, the head of real estate at Holland & Knight, recruiting is markedly more aggressive now than it was even a few years ago. “It’s certainly increased over the past six or seven years,” he said. “The reason is, there were no new real estate lawyers minted between 2007 and 2012.” Attorneys who weathered the layoff storm of the financial crisis continued to gain experience during those years, making them hot commodities once firms began hiring again, he said.

“I’ve had three calls from recruiters today, and I’m not even exaggerating,” said Carl Schwartz, who noted that they are often trying to get him to jump ship. (He moved to Hunton & Williams from Herrick Feinstein, in 2012). Headhunters in the industry can be relentless — “there are some guys who are more obnoxious about it than others,” he added.

Landing talent from competing firms has been key for many of the top legal shop’s expansion plans. Last year, Stroock hired away seven attorneys from global law firm DLA Piper for its Washington, D.C., and New York offices. Kramer Levin, meanwhile, poached current partner Andy Charles from international firm King & Spalding in May of last year. “We’re always looking and accessible. We like talent, and we like to buy talent, but we’re not out there aggressively calling people, saying, ‘So, you want to come to Kramer Levin?’ ” said Neveloff. He also noted that Kramer Levin recently lost one of its own to an in-house counsel position at WeWork. Ivanhoe said Greenberg Traurig brings in about three associates a year, “and the rest of our hiring tends to be opportunistic. In general, there’s a fair amount of mobility between firms,” he said. To retain attorneys, “you have to give them good work, you have to provide good mentorship and training; they have to see that there’s a future,” he added. Duval & Stachenfeld’s Stachenfeld said there’s a lot of competition for “top-quality partners that either are super talented at servicing or have a solid institutional book of business.” For the moment, law firms don’t seem to be cutting billing rates. Most said they evaluate that at the end of the year, so any cuts will depend on where the market is then. As for retaining attorneys when the market turns, Saft said that it’s crucial to have a steady stream of business from areas buffered from market conditions.

“It’s general corporate representation of real estate companies and the kind of things lawyers involved in big deals would find to be boring,” he said, citing co-op and condo board representation and affordable housing as examples. But he added: “When the billion-dollar deals disappear and the workouts and the bankruptcies resulting from a downturn slow, then it becomes important.”

Eda Kouch and Yoryi De La Rosa contributed research to this report