TRD Special Report: Shortly after Jason Freedman founded 42Floors in 2011, he began a blog about his office listings startup. The blog evolved into a public diary, a window into the fortunes of the company. “We’ve got big ambitions. It’s still a long road to go, but we’re pumped,” Freedman wrote in January 2013, the day the company announced a $12.4 million Series B funding round.

By February 2014, the startup had moved into new San Francisco digs. “So is 15,000 sq. ft. too big for us?” he wrote at the time. “We figure we can fit up to a hundred people in there. That means that we would have to double and then double again.”

A year later, the mood had turned. In March 2015, the company laid off half its employees and shuttered its brokerage division. “These last few months have been incredibly painful for me, (…)” he wrote in July 2015. “I fucked up and my employees paid for it.” It was one of Freedman’s last posts.

Today, Freedman told The Real Deal, the company has more staff and users than ever before. Still, 42Floors’ ups and downs are emblematic of the broader challenges startups in the commercial real estate space face. Between 2011 and 2014, 129 real estate tech companies were launched in the U.S., according to research firm PitchBook, and many have become successful businesses. But not a single one has yet reached a $1 billion valuation, and by any measure, their collective impact on how the real estate industry does business has been far from transformative. “Technology impacts so many areas and aspects of what we do, but has not changed across the board how we do things,” said Sara Shank, head of portfolio management at Beacon Capital Partners.

From unicorns to cockroaches

Real estate seemed like the ideal candidate for a tech revolution. The total value of all developed real estate worldwide hit $217 trillion in 2015, according to a Savills estimate. Leasing real estate was the second-most profitable industry in the U.S. in 2015, with average net margins of 16 percent, according to Forbes. But despite its enormous size and profitability, the industry is widely considered an inefficient dinosaur. What better field, then, to disrupt with software?

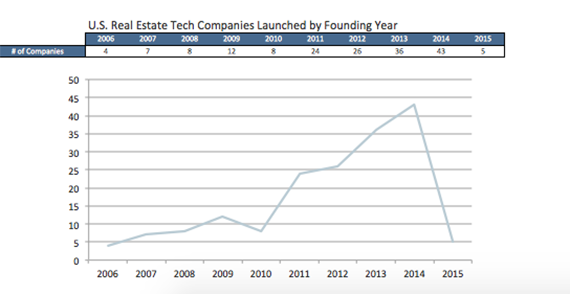

Or so thought the entrepreneurs who launched real estate tech startups in unprecedented numbers over the last five years. Between 2006 and 2010, an average of 7.8 real estate tech companies sprouted up annually, according to PitchBook, whose database isn’t comprehensive but does indicate a general trend toward less startup activity. In 2011 the number jumped to 24, rising every following year until it hit a peak of 43 in 2014 (see chart).

The number of U.S. real estate tech startups by year (credit: PitchBook)

There had been real estate tech startups before, and some of them, such as Zillow, Trulia and LoopNet, were home runs. But most of them were geared to consumers, allowing them to look for apartments or office space online and providing more context and transparency.

In contrast, the startups launched since 2011, with some exceptions, focused on serving real estate companies. Crowdfunding firms and institutional funding platforms like Fundrise, Cadre and LendingHome promised real estate investors and developers an easier (and cheaper) way to raise money. Companies like Hightower, VTS and Honest Buildings offered major landlords software to better manage their portfolios and projects. Data platforms like Reonomy and CompStak offered brokers and investors better access to property-specific information. These startups believed that by making the industry more efficient, they could capture a share of its profits.

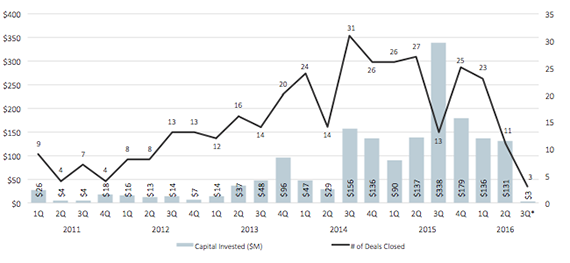

But it’s clear that the great CRE tech startup boom is now over. From its 2014 peak, the number of new startups crashed to five in 2015, according to PitchBook. Venture funding deals are still happening (see chart), but the second quarter of 2016 saw the fewest deals in four years. Observers say investment is now harder to get, and more often goes to somewhat established tech companies or those with industry connections rather than to fresh startups.

Venture funding for U.S. real estate tech companies (credit: PitchBook)

“Series A rounds are being done at significantly lower valuations than 12 months ago,” said Zachary Aarons, co-founder of real estate tech accelerator MetaProp. “It’s become a buyer’s market again – it’s just like the real estate market.”

So far, very few high-profile real estate startups have folded. But observers say it’s just a matter of time.

“I think there a lot of companies that maybe don’t have a viable, sustainable, scalable business model,” said Richard Sarkis, co-founder and CEO of Reonomy. “A lot of entrepreneurs sort of got papered over by financing round after financing round. That was keeping the lights on.”

Ted Koltis, a leasing executive at Paramount Group, which uses VTS, said real estate “is fairly nuts and bolts. So I’m not sure how much technological advancement it really needs.”

Venture investors assume that the vast majority of startups they bet on will fail. But they get in the game with the assumption that the few that survive will pay off handsomely. So far, CRE tech startups have not lived up to that side of the bargain. Although plenty of them appear to be doing well, the big startup wave has yet to produce a successful IPO, or even a likely near-term candidate for one. Of course, WeWork is valued at $16 billion and Compass at $800 million. But much as they like to position themselves as tech firms, they are, at heart, a short-term space company and a residential brokerage.

“No one’s seeding the next generation of real estate tech because the exits aren’t there,” said Ashkan Zandieh, founder of property data startup Falkon and research company RE:Tech. David Eisenberg, co-founder of Floored, said he is not convinced “that outside of WeWork there is a public company lurking in the real estate tech space.”

Reonomy’s Sarkis argues that faced with slower-than-expected growth, venture investors have lowered their expectations. They are no longer looking for unicorns (startups that hit a $1 billion valuation) but for “cockroach startups”: companies that don’t grow as quickly, but prove resilient in the long run.

The blame game

Most CRE tech startups were always expected to fail. But why aren’t those that offer a useful product and viable business model blowing up?

Floored’s Eisenberg puts part of the blame on the big firms that shape the industry. While other industries like finance have long invested heavily in technology — global fintech investment grew 67 percent year-over-year to $5.3 billion in the first quarter, according to Accenture — real estate has lagged well behind. When Eisenberg pitches Floored, he said he’s often dealing with companies that have neither dedicated personnel nor budgets to adopt technology on a significant scale.

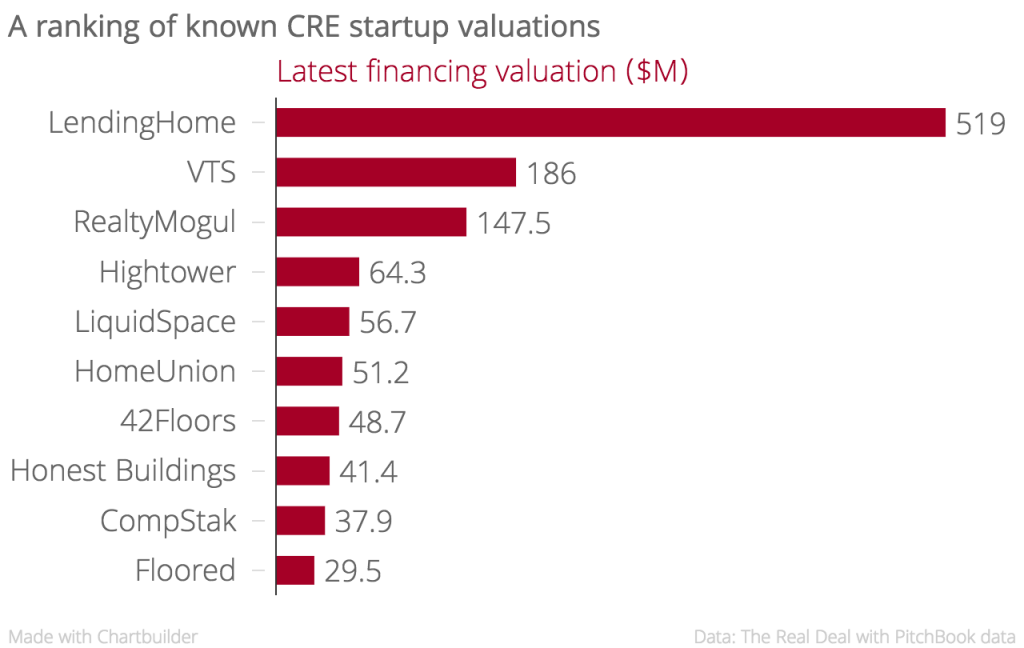

Some of the industry’s most valuable CRE tech startups (Credit: The Real Deal with PitchBook data)

“You’re not fighting against a competitor, you’re fighting against inertia,” he said. He described a “mental overload” among busy CRE executives who have to deal with startup pitches on the side, which creates a roadblock to committing to technology.

“It’s just not high on the to-do list to install something new – there is always this traction problem,” said Michael Rudin, an executive at Rudin Management. “There are a lot of pitch books and companies out there, and it’s not an area that, until recently, a lot of companies focused on.”

In this limited-attention environment, the startups that thrive are likely to be those that meet as many needs as possible in a single product. Hightower and VTS, which offer comprehensive software tools for real estate portfolios, fit this mold, and several sources said they are among the startups on the firmest financial footing.

Conversely, companies offering “point solutions” – or technology that addresses a very narrow, specific part of a real estate company’s business – seem to struggle. “The attention span issue is a real problem for the industry,” said Brandon Weber, founder and CEO of Hightower.

Some companies form alliances to sell point solutions as part of a broader package. Crowdsourced leasing comps provider CompStak, for example, struck deals with VTS and Hightower to include its comps in their products. Weber said his peers approach him about partnerships increasingly often, but he still believes the CRE tech space will consolidate into a small number of broadly applicable products.

There are signs that major players are taking CRE tech more seriously. In June, JLL bought tech consultancy BRG and established a new “technology solutions” division headed by BRG’s former CEO Traci Doane. Also in June, CBRE hired Capital One’s Chandra Dhandapani to be its chief digital and technology officer. The brokerage recently sent an 11-person delegation of high-level executives to New York to meet with tech startups, including Floored, according to Eisenberg.

As millennials move up the corporate ladder, CRE tech will get its day in the sun, Eisenberg said. But it may be too late for many startups by then.

“The companies that will benefit are those that did more with less money,” he said.

Misguided force meets immovable object?

Not everyone agrees that real estate firms are neglecting technology. “I think the opposite is true,” said Beacon Capital’s Shank. “In the past, real estate never seemed sexy enough to tech firms. Technology found plenty of other industries before it found real estate.”

Tal Kerret, president of Silverstein Properties and an investor in Fundrise, called the notion that real estate companies aren’t open to technology a “joke.”

“If they can make my life easier and save costs I will jump and hug them,” he added.

Instead he argued that some entrepreneurs fail because they underestimated how complex real estate is. To him, there are two kinds of startups: disruptors who want to replace established players, and optimizers who merely want to help them work more efficiently.

“Many of the early players wanted to be disruptors, and the real estate industry is not looking for disruptors,” he said. What Uber and Airbnb did to transportation and hospitality is much harder to pull off in real estate, he argued, given the size, complexity and stakes involved.

Eisenberg challenged that notion. “There are people who are building virtual reality office experiences that will compete with traditional office space, there’s no doubt in my mind,” he said. Real estate insiders were “often underestimating the rate at which technology is changing the world. They’re almost treating technology like a thing that will come and go.”

Even some of the so-called optimizers, Kerret said, fail to understand how the industry operates. Building a skyscraper takes a long time, and developers will only partner with startups if they are confident they will still be around when it is completed. “How will I know they will exist five years from now?” Kerret said. “It’s an inherent problem for the young startups that don’t understand slow speed.”