If you asked a real estate executive to rank property types by bubble risk, odds are they’d start with condos. Then, probably retail with its precariously high vacancy rates. Third might be the office market, where supply has surged. Way down in the bubble-risk ranking would likely be multifamily: the asset class in which, conventional wisdom goes, rents tend to rise and never crash (not even during the depths of the 2009 recession).

With that in mind, you’ll forgive this reporter for almost falling out of his chair when Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, picked multifamily lending as one of the two greatest near-term risks to U.S. financial institutions (along with automobile loans). And Zandi isn’t alone.

As early as December 2015, federal banking regulators issued a joint statement warning that banks’ increased commercial real estate and multifamily lending poses a threat to financial stability. In April 2016, Madison Realty Capital’s [TRDataCustom] Michael Stoler wrote an op-ed warning that “trouble might be coming” for loans backed by rental apartment buildings.

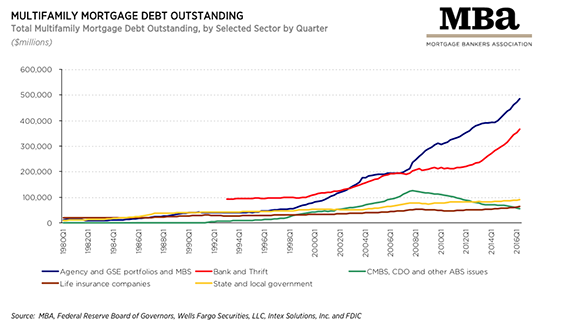

But lenders haven’t slowed down. Between the first and second quarter of 2016, the volume of outstanding multifamily debt in the U.S. grew by $27.6 billion to $1.09 trillion, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. Since 2007, the dollar volume of multifamily debt held by banks, thrifts and bond investors has more than doubled (see chart). And in the trade group’s year-end survey, 92 percent of lenders said they had a “strong or very strong appetite” to issue new commercial and multifamily loans.

Banking regulations accelerate this trend. Under the international Basel III guidelines adopted by U.S. regulators in 2013, multifamily loans on banks’ balance sheets only receive half the risk-weighting of other commercial real estate loans (provided certain leverage conditions are met). This means banks doing multifamily loans need to hold less capital as an insurance against losses, making such mortgages more attractive compared to office or construction loans.

Are we at risk of a multifamily mortgage bubble?

Credit: Mortgage Bankers Association

It is precisely the multifamily market’s perceived stability and crash-resistance that should give investors pause. While the single-family housing and office markets have fallen on their faces in recent memory, “multifamily has done a much better job over the last 25 years or so of not falling into the boom and bust trap,” said Sam Khater, an economist at CoreLogic who is bullish on the market. This record reinforced the belief that apartment buildings are a safe investment. And unlike Japan and Germany, the U.S population is growing and homeownership is still reeling from the subprime mortgage crisis. This has translated to rising demand for rental apartments, pushing up rents and investors’ profits. It’s also seen some of the biggest investors, such as the Blackstone Group and Starwood, go full-tilt on multifamily.

But just because an asset class has strong underlying demand and a track record of stability doesn’t mean it’s immune to a crisis.

“Like all markets that get overdone, they start with good fundamentals — good logical reasons why you would invest there,” Zandi said.

Bubbles can form in any asset class, but they are particularly dangerous in those perceived as unsinkable. Take the U.S. housing market. Prior to 2007, many investors and observers argued that the housing market would not crash because it was too large, diversified and had proved its stability. This false sense of safety, exacerbated by too-easily available credit, helped inflate the bubble long after skeptics began warning of a crash in 2005, ultimately worsening the downturn.

In contrast, markets that are perceived as risky from the outset are often better able to self-correct. Take Manhattan’s condo market: lenders began turning off the cash spigot in 2015 as soon as signs of slowing apartment sales emerged. This left some developers lacking funding, but probably also saved banks from painful losses.

As of May 2016, more than 500,000 apartment units were under construction in the U.S. — almost twice the historical average and the highest total since 1985, according to CoStar (see chart). In some southeastern cities like Nashville, Charleston and Fort Myers, new construction as a share of existing inventory is precariously high. In New York, new supply is still widely regarded as lagging behind demand and nobody expects the market to hit a prolonged downturn amid strong fundamentals. But the risk is that investors overestimate the potential for future rent increases and overpay for properties.

Between December 2015 and December 2016, the average apartment rent fell by 2.5 percent in Manhattan and by 3.8 percent in Brooklyn, while concessions rose dramatically, according to Miller Samuel data. Apartment landlord Equity Residential said this week that same-store profits at its New York apartment buildings fell 3.1 percent in 2016. Despite this slowdown, investors continued to bid up multifamily prices, which rose 1 percent in Manhattan and 9 percent in Brooklyn and 15 percent in Queens, according to a recent Ariel Property Advisors report. As interest rates climb, some may struggle to refinance their own aggressive bets.

“Today’s near-term outlook is more uncertain than in recent years, with plenty of headwinds, including the tightening of credit markets after the election, as well as higher rental supply, which is causing free market rents to plateau or fall,” Ariel’s Shimon Shkury wrote in the report.

Earlier this week, Madison Realty Capital filed to foreclose on an East Village apartment building after its owner, Raphael Toledano, defaulted on a $34 million loan — offering a taste of how multifamily investing can go wrong.

Across the country, leverage on multifamily buildings is still low. The average loan-to-value ratio on newly issued Freddie Mac multifamily loans rose to 71 percent in 2015. While up from 59 percent in 2013, that’s not far off the historical average. And it would be far-fetched to argue that today’s multifamily market resembles 2007’s. But don’t let that lull you into complacency.

“Many people all over the world seem to have thought that since we are running out of land in a rapidly growing world economy, the prices of houses and apartments should increase at huge rates,” Yale economist and Nobel laureate Robert Shiller wrote in 2009, analyzing the subprime mortgage crisis. “That misunderstanding encouraged people to buy homes for their investment value – and thus was a major cause of the real estate bubbles around the world whose collapse fueled the current economic crisis. This misunderstanding may also contribute to an increase in home prices again, after the crisis ends.”

(Read more of The Long View here.)