In 2015 and early 2016, the Israeli bond market had become the Promised Land for U.S. developers. Players here had raised hundreds of millions of dollars in cheap debt from Israeli investors, and the nascent financing model was expected to become a long-term source of funding for U.S. projects, particularly as EB-5 was going through legislative challenges.

Then came Urbancorp. The Canadian condominium developer, which raised $48 million through an issuance on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange in late 2015, filed for bankruptcy protection in April 2016, and the Israel Securities agency suspended trading of its bonds. The price of the bond had plummeted earlier that month when it became apparent that the Toronto-based company was severely overleveraged and facing significant issues back home, which it had failed to disclose.

The Urbancorp fiasco triggered panic in the Israeli market over “The Americans,” the crop of U.S. real estate companies that, by then, had issued over $2.5 billion in debt.

“All the American companies went down,” said Rafi Lipa, a principal at Victory Consulting, a Tel Aviv-based firm that brought the first U.S. company to market in 2008. “You couldn’t trade a dime.”

A year later, however, the market has rebounded – and then some. So far this year, U.S. firms have raised over $1 billion on the TASE, eclipsing the roughly $945 million raised in all of 2016, according to data from InFin, a consulting and underwriting firm that helps U.S. developers raise funds in Israel. And what’s more, the terms these developers are getting on the market are now closer to what their Israeli peers get, showing that, after a decade in the game, U.S. firms are no longer a novelty, but a tried and tested investment option.

It’s not just that the market has gotten bigger. There’s also a sense, sources both in the U.S. and Israel said, that the investment community in Israel is beginning to price each U.S. company on its merits, rather than judge them as a pack.

In the past “everyone called them ‘the American companies,’” said Meital Navon, an analyst at Ramat Gan-based More Investment House who specializes in American real estate. “They didn’t distinguish between multifamily or luxury or development.”

In the last few months, both newcomers and veterans were greeted with high demand and low interest rates. Jeff Sutton’s Wharton Properties raised $243 million in January with a 3.9 percent interest rate; David Marx’s Marx Development Group issued a bond at a 3.75 interest rate in March, and Joel Weiner’s Pinnacle Group raised $120 million at a 3.6 percent interest rate in April. In each case, the interest rate was the lowest of any U.S. company at the time.

In April, there was $4.1 billion in bonds issued by 21 U.S. companies trading in the Israeli market, comprising roughly 5 percent of the total corporate bond market in Tel Aviv, according to InFin’s data. That kind of deal flow could mean lower interest rates but greater scrutiny.

U.S. firms have been on the market since 2008, when Abraham Leser’s Leser Group, a commercial landlord, came to the market. Leser was essentially required to make an initial public offering in Israel. To do that, he created an entity, incorporated in the British Virgin Islands, that controlled a collection of his New York properties, and that entity issued the bonds. (Read The Real Deal’s step-by-step guide on how U.S. developers go about issuing debt in Israel.)

The Great Recession brought a halt to any such activity for a stretch, but by 2014, more companies were giving it a try. At first, Israeli investors were resistant. Despite the extensive disclosures required for a company to IPO in Israel, these were ultimately unknown companies with no public track record. Few institutional investors had the stomach or the staff to analyze the particulars of the Brooklyn multifamily market versus the Manhattan luxury condo or high-end retail markets.

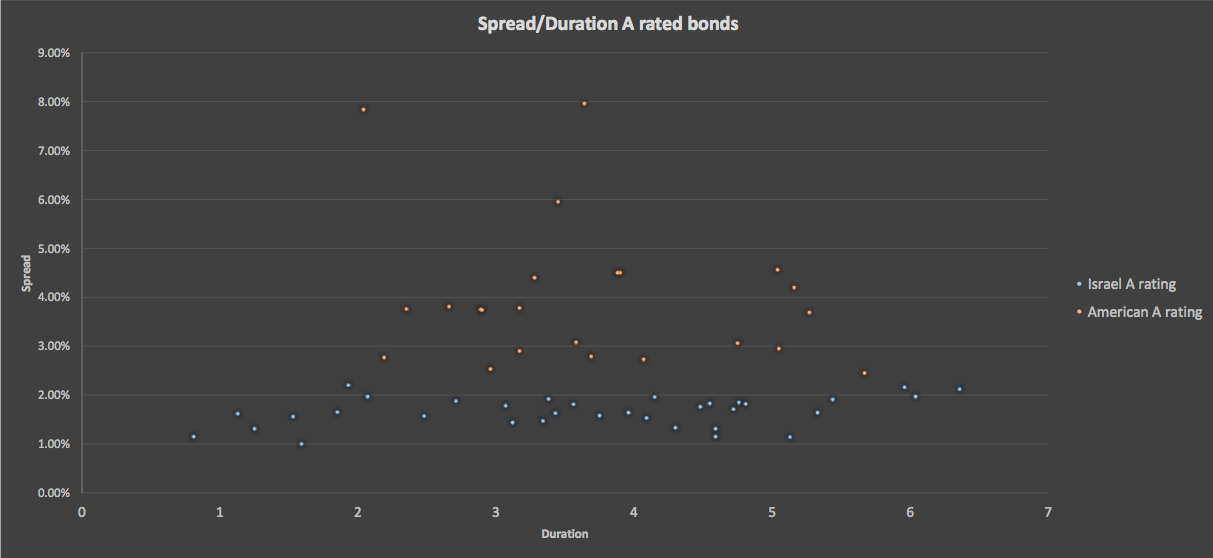

That was reflected in the interest rates that U.S. companies would receive, which were consistently higher than similarly-rated Israeli companies.

“We tend to tell our clients, when they first come to market they’re going to pay the ‘new kid in town’ price,” said Joe Berko of Berko & Associates, a Manhattan-based brokerage that advises firms entering the Israeli market.

But to the right investors, the spread made U.S. firms especially attractive. The higher interest rates awarded the U.S. companies were an opportunity, especially with rates so low everywhere else, since the risk they reflected was the fear of the unknown, rather than an actual danger that the companies would default.

By 2015, the market was in full swing. More than 15 companies across a variety of sectors, primarily based in New York, but with assets in Florida, Dallas, Missouri and Michigan, had entered the market, and investors were lapping it up. Gary Barnett’s Extell Development raised $360 million in its IPO in 2014. Shortly afterwards Barnett was joined by the likes of Pinnacle, Joel Gluck’s Spencer Equity and Joseph Moinian’s Moinian Group.

“At some point in 2015, there was a lot of enthusiasm, because the yields were high,” said Navon of More. “But in my opinion there wasn’t enough analysis.”

Urbancorp raised its debt in late 2015 at an interest rate of 8.65 percent. When the company missed the deadline to release its year-end earning report in March, the bond price collapsed, and the ISA halted trading on its bond. Urbancorp then filed for bankruptcy with a plan to restructure in what appeared to be an attempt to bypass the bondholders, but an Israeli court ruled against the company, insuring that the recovery process would have to proceed through the Israeli legal system.

“After Urbancorp, the market went into a holding pattern,” said Avital Bar-Dayan, a financial consultant and former executive at Midroog, an Israeli rating agency.

“Everyone got hit,” said David Marx, whose firm IPO’d in November 2015.

In retrospect, Urbancorp’s financial situation might have been clear if anyone was looking, said Chen Schreiber, an independent financial consultant who has called for more scrutiny of the U.S. companies. “It looked like we couldn’t read a prospectus,” he said, blaming the situation both on Urbancorp’s lack of disclosure and investor giddiness.

To make matters worse, New York’s luxury market, which was consistently breaking records in 2015, had begun to soften. The Israeli bond market turned on Extell, the only one of the U.S. firms raising Israeli debt that specialized in luxury residential development. In May 2016, there was a widespread selloff of Extell bonds, causing yields to soar to 15 percent.

“I feel bad that some of the original investors who bought in at par then for whatever reason decided to sell at a loss,” Barnett told The Real Deal in March, maintaining that it was a mistake to sell. “I feel bad about that, but we did do everything we were supposed to do. There were projects that people didn’t think we’d get everything done at, but we did get everything done. Not a one of them failed.”

Israeli investors turned hostile. Several companies who were in the midst of the IPO process, such as Joseph Tabak’s Princeton Holdings and Simon Baron Development, withdrew from the market after receiving cold ratings, or simply in response to a wary market.

By the fall however, the market began to thaw. In September, the Florida-based Copperline raised $19 million over a weekend to finance an acquisition in Broward County, and in November, Wiener’s Pinnacle Group, which goes by Zarasai in Israel, issued its fourth bond at an interest rate of 4.35 percent. Pinnacle’s bond was oversubscribed by 300 percent, according to Lipa, and all five of Israel’s insurance companies made a bid for the bond, in a first for the market.

These weren’t first-timers. Pinnacle, in particular, was a popular player on the market, whose bonds were trading at consistently low yields. “The market really likes Zarasai,” said Navon. “[Wiener] is very committed. It’s important to him to raise more money and to maintain good relations with investors.”

This was an indication that Israeli investors were regaining confidence, and had begun differentiating between the various companies.

Once companies have been on the TASE for a while, the market has been able to watch them in action and see them complete developments, close on acquisitions, and grow their rental income — or not. In many cases that has meant drops in yields and interest rates. Bonds for the Moinian Group, for example, were trading at about 3.6 percent in April, down 60 basis points, from where they started, at 4.2 percent. And when companies issue their second, third and fourth bonds, interest rates tend to drop as well. Pinnacle, for example, raised its first bond at 4.95 in early 2014, and with one exception, has been awarded successively lower rates, ending with the 3.6 percent rate in April.

In March, two A-minus rated companies issued Series B bonds raising between $70 million and $80 million. Allen Gross’s GFI Real Estate issued at 5.75 percent, a significant drop from the 7.75 coupon on their first bond, indicating that investors perceived the bond to be less risky. Marx Development issued at 3.75 percent, the lowest interest rate at that point.

Since Marx’s bond was secured by two properties, while GFI’s were classic corporate bonds, the comparison isn’t quite apples to apples. But the spread also reflects the difference in their businesses, a source familiar with the deal said. GFI is in the hotel business, a much more vulnerable sector than Marx’s assisted-living focus.

Of the first-timers, several, such as Igal Namdar’s Namco Realty, aren’t focused on New York, which means more legwork for Israeli analysts, who have to learn more sectors and more markets as the field expands.

U.S. companies are still trading above similarly situated Israeli companies, and while the spread is tightening, this will likely continue to be the case, partially because there is some inherent risk in dealing with foreigners. Which means, that for those willing to accept that risk, the payout is greater.

“We’re almost there,” Lipa said. “We are very close to the Israeli companies. “The smart investors started to see that not everyone is Urbancorp.”

Yossi Levi, a principal at InFin, says he was never concerned that Urbancorp’s damage would be lasting. “We weren’t concerned about the model,” he said. “The structure is strong enough to survive even a fraud case. I think the fact that the investors are getting the vast majority of the cash back is comforting for the investors.”

As the sector grows, the market evolves and adopts different financial structures. In the last several months, two companies issued bonds secured by a first position, and received some of the lowest interest rates for U.S. companies. The first to make it to market was Yoel Goldman’s All Year Management, who raised $166 million secured by a first position on the William Vale hotel in Williamsburg. Marx followed with a bond secured by a first position on two assisted-living facilities in Brooklyn.

The market has also become less hostile to other changes. When Moinian first used the proceeds from the bond issue to lend money, back in 2015, the market balked. But when Moinian recently lent $160 million on developer Solomon Feder’s condo conversion project in Brooklyn, with what remained of the $361 million he had raised, the bond price ticked upwards.

Not everyone believes the market has learned its lesson. “Companies that should not be getting in are getting in,” said one analyst well-versed in the market.

In addition, while yields seem to indicate that the market has learned to distinguish Extell’s glitzy projects from Gluck’s multifamily portfolio, the analyst says that’s in good times only.

“If one takes a hit, they’re all going to take a hit,” the analyst said, because they’re correlated in the people’s minds.

Marx said that in the long run, the Urbancorp saga would be seen as a positive. “It tested the market, and ultimately strengthened the market,” Marx said. “It’s like a relationship. When you recover from the first fight it strengthens the relationship.”