There was more fanfare than normally accompanies an office lease when Spotify earlier this year inked a deal to expand its Manhattan offices in a relocation to 378,000 square feet at Silverstein Properties’ [TRDataCustom] 4 World Trade Center.

The popular music-streaming app needed the extra elbowroom as it planned to add 1,000 new jobs. Gov. Andrew Cuomo — who offered up to $11 million in rent rebates — even broke out his Spotify playlist.

— Christopher Esposito (@crabioscar) February 15, 2017

The deal illustrated a tidy correlation between employment growth and leasing activity: Spotify was more than doubling the size of its workforce, and it was moving into a new office twice the size of its old one.

Now, as another three-month period comes to a close, economists and data wonks are busy crunching numbers on employment for the quarterly ritual of analyzing Manhattan’s job growth and office leasing activity. And while conventional thinking might reason that office leasing is directly related to the number of jobs added, experts say the correlation is – at best – a loose one, and there many other factors at work when it comes to leasing activity.

“I don’t think there’s as much science to it as you might think,” Cushman & Wakefield executive vice chairman Patrick Murphy said. “It’s all very macro, and I don’t know that anybody takes what the economists are looking at and takes it right down to the availability rates, but there are general trends.”

“It’s a general indicator,” he added.

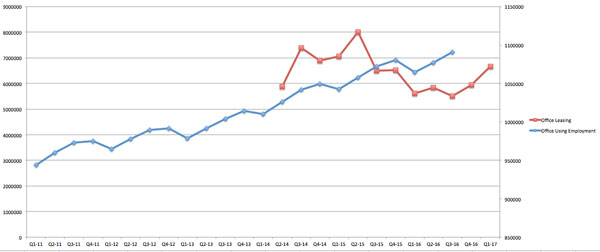

In fact, looking quarter-to-quarter, one would be hard-pressed to interpret how job gains are affecting the office leasing market. Using data from the state Department of Labor on six “office using” employment sectors, The Real Deal charted employment gains over the last few years against leasing data provided by CBRE.

Office-using employment growth and leasing activity in Manhattan (source: TRD analysis of data from the state Department of Labor and CBRE)

What the chart shows is that jobs usually follow a smooth arch, the ups and downs of which can be measured against years-long economy cycles. Office leasing, however, is more “lumpy” from quarter to quarter, swinging erratically at each interval.

“I think generally speaking, it’s good news when office employment is growing and it will ultimately translate into more business,” said Nicole LaRusso, head of tri-state research at CBRE. “There are a lot of things that influence leasing activity that don’t have anything to do with employment.”

What drives leasing?

While job growth certainly plays a factor in leasing activity, experts say market fundamentals do more to dictate how active tenants are. Expensive rents and tight availability, for example, will put a damper on leasing, while activity will pick up when space is more affordable and available.

“When employment peaked in 2007, the market was tight and rents were high, but activity slowed: there wasn’t much good space and it seemed expensive,” said Tristan Ashby, the director of research in New York for JLL. “As the market weakened, we saw a lot of early renewals as large tenants locked in lower rates.”

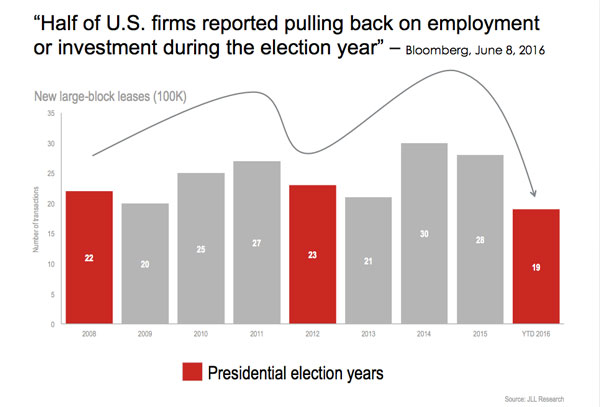

There are times when job growth and leasing move in tandem, such as when there’s a general sense of uncertainty in the market. Job growth and leasing activity took a pause in 2016 as happens every election year, Ashby said.

Leasing activity during election years (source: JLL)

Regardless of employment, leases expire on set terms, and expirations and renewals will always drive a certain amount of activity in each quarter. And while companies can move relatively nimbly when it comes to the size of their workforce, leasing decisions operate on longer timelines.

“Because office leases are signed every 10 to 15 years, that time frame makes it hard to manage how much space to lease on a 10-year basis,” said Barbara Denham, chief economist at the commercial real estate data company REIS. “It’s really hard not knowing what the economy is going to look like.”

And not all new jobs are created equal.

Earlier this year, the commodities firm Glencore signed a 60,000-square-foot lease at Vornado’s 330 Madison Avenue to relocate its offices from Connecticut. That’s an example of a direct correlation between job growth in the city and leasing.

But other companies may not have such a direct need for new space as they hire new employees.

Cushman’s Murphy said many companies laid people off in the downturn of 2008 but didn’t actually put their space on the market. He recently met with a company that has 400,000 square feet, but only uses about 65 percent of its space.

“So most companies keep warehouse of about 10 percent so that they have room to grow,” he said. “My experience is that sometimes a company may be hiring people, but they’ve got enough space in their inventory that they don’t actually need to take new space.”

And it’s been well-documented that tenants now require less space as they densify offices with open floor plans and move into new buildings with more efficient floor plates. That trend has had a remarkable impact on the relationship between employment and occupied office space in Manhattan

In previous economic cycles, such as the run up before the dot-com bust in the early 2000s and the most recent one before the Great Recession, Manhattan’s office employment and the square footage offices occupied have generally correlated with each other.

Employment and occupied office space (source: Savills Studley)

But beginning in the recovery that started in early 2009, the two began moving in opposite directions. While office employment grew from about 920,000 jobs in December 2009 to shy of 1.1 million as of June, occupied office space actually declined from nearly 523 million square feet to about 515 million square feet during roughly the same time, according to Savills Studley.

“Since 2009 or so we have definitely been adding workers, but the amount of occupied space that they’ve been taking declined as companies go to smaller and smaller footprints,” said Heidi Learner, Savills Studley’s chief economist. “Over that period of time we’ve added almost 200,000 jobs, but the amount of occupied office space declined.”

Divining the numbers

Given this loose relationship between jobs and leasing, how does a landlord interpret employment numbers when devising a leasing strategy?

Rudin Management Company CEO Bill Rudin said that while he pays attention to the overall numbers, he looks deeper at what kinds of business are driving growth in order to determine how to attract the kinds of tenants showing the most growth.

“It’s not just the number of jobs, but what are those jobs? Who is expanding? Is it TAMI, financial services, healthcare?” he said. “Obviously, job growth is very critical. It helps drive us to think about where we’re investing.”

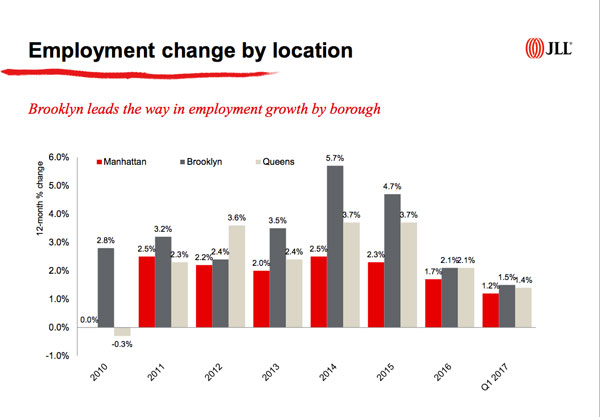

And Jeremy Moss, the head of leasing for Silverstein Properties, said that beyond the broader trends, it’s more meaningful to look at where the newly created jobs are filling offices, noting that the expansion of the office market into places like Brooklyn and Long Island City mean landlords have to think in new ways about how job growth affects the market.

Job growth is disproportionately more robust n the outer boroughs (source: JLL)

And he warned against drawing conclusions from one or two quarters of data.

“It’s kind of like watching your favorite sports team. You can’t obsess over every game; you have to look at the whole season,” he said. “The same is true of job growth.”