From the September issue: New York City has a long, storied tradition of families shaping its skyline. Family-run businesses like the LeFrak Organization, Tishman Speyer, Rudin Management and the Durst Organization are local legends, known for taking on major development projects and holding on to some of the city’s largest assets across three or more generations.

It’s not an easy time, however, for the family dynasties on the rise.

A field once dominated by those well-established families is now increasingly crowded with other sophisticated players. Over the last several years, well-polished corporate machines have taken over the city in the form of real estate investment trusts and other large companies.

Some real estate owners think investors eager to enter the market are less discerning about who they lend to — no longer relying on what family-run companies often tout as their greatest asset: reputation.

“It seems like people out there are like Teflon,” said Justin Elghanayan, president of Rockrose Development, whose father and uncles founded the firm back in 1970. “They can get away with projects going sour and still be funded by investors wanting to get into the market. The fact that investors can be forgiving of these developers who promise a fast buck is a challenge.”

Back in October 2013, The Real Deal ranked some of New York’s longest-standing real estate dynasties — the industry’s household names. But this time around, instead of revisiting those gold-star players, we took a different approach, looking at the private firms that have the wheels in motion to become New York’s future dynasties. Rather than looking at companies that were started three generations ago, we looked at second-generation firms where the children have taken (or are being groomed to take) the reins. (Companies like the Trump Organization and Silverstein Properties, which were started three generations ago under different names, were not included.)

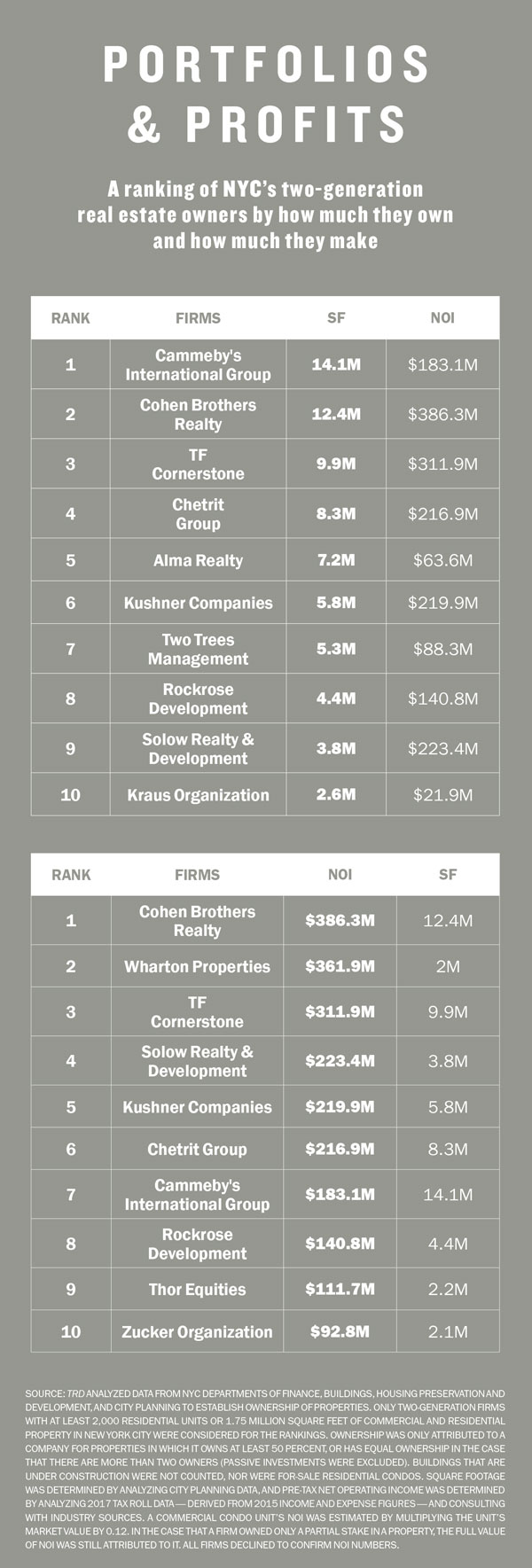

To determine which next-generation firms are leading the pack, we compiled two separate rankings: one based on the size of the companies’ portfolios and the other based on profits.

To qualify, firms had to own at least 1.75 million square feet of property (either commercial or residential) or at least 2,000 residential units in New York City (projects currently under construction or in planning were not counted).

We pored over thousands of property records from the city’s Department of Buildings, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development and our own internal database to determine the size of each firm’s footprint. Then we calculated each firm’s net operating income by combing through the most recent figures available from the city Department of Finance and consulting industry sources. The companies, which are all privately held, did not confirm their NOIs, which because of lags in tax records, were all from 2015.

From there, we narrowed the pool down to the 10 largest two-generation owners and the 10 most profitable.

The biggest, the richest

Cammeby’s International Group clocked in at No. 1 on the ownership ranking, with a total of 14.1 million square feet.

The firm was founded in 1967 by the under-the-radar investor and developer Rubin Schron, and two of his sons — Avi and Eli — now work there. The company ranked No. 7 on the NOI list, raking in $183.1 million in profits in 2015.

Cohen Brothers Realty, which is headed up by Charles Cohen, the son of one of the firm’s founders, meanwhile, had the second-largest portfolio, with 12.4 million square feet. But it topped the arguably more-coveted NOI list, with its properties throwing off $386.3 million in revenue for 2015.

TF Cornerstone snagged the No. 3 slot on both lists, with 9.9 million square feet in holdings and $311.9 million in earnings. The firm — which was spun off from Rockrose back in 2009 following a family split — is headed by founders and brothers Tom and Frederick Elghanayan. Several of their heirs, including Jake Elghanayan and Zoe Elghanayan along with Tom’s son-in-law Jeremy Shell, now work at the firm.

The Chetrit Group, headed by brothers Joseph and Meyer Chetrit, and Alma Realty, founded by Efstathios Valiotis in 1988, rounded out the top five, with 8.3 million square feet and 7.2 million square feet in holdings, respectively.

Kushner Companies — which, of course, has been in the news nearly daily, given that its former CEO Jared is now in the White House working for his father-in-law — followed with 5.8 million square feet and came in at No. 5 on the revenue ranking, with nearly $220 million in NOI.

The firm is now being officially run by Laurent Morali, but sources have said that Jared’s dad, Charles Kushner — who stepped down in the aughts after he got into legal trouble, for which he did a short prison stint — is really pulling the strings behind the scenes. And Jared’s sister Nicole Kushner Meyer has also taken on more responsibility at the firm.

Two Trees Management, Rockrose, Solow Realty & Development and the Kraus Organization filled out the Top 10 on the ownership chart. It should be noted that Sheldon Solow’s namesake firm — where his son Stefan now works — ranked No. 4 for NOI with $223.4 million in revenue in 2015. Not surprisingly, much of that came from his trophy office tower at 9 West 57th Street.

Meanwhile, two retail kings who were both absent from the ownership list made their way onto the NOI ranking. Wharton Properties, headed by Jeff Sutton, came in at No. 2 on that list, with $361.9 million in revenue from 2 million square feet in property, including trophy towers like 717 Fifth Avenue and 650 Fifth Avenue. Sutton’s son, Joseph, is working to expand the company’s residential holdings.

Similarly, Thor Equities, headed by Joseph Sitt, took the No. 9 spot with $111.7 million in profits from 2.2 million square feet in holdings. A spokesperson for Sitt, whose son Jack works at the company, said the firm rejects the idea of being “family-run.”

Similarly, Thor Equities, headed by Joseph Sitt, took the No. 9 spot with $111.7 million in profits from 2.2 million square feet in holdings. A spokesperson for Sitt, whose son Jack works at the company, said the firm rejects the idea of being “family-run.”

The Zucker Organization — run by Donald Zucker and set to be taken over by his daughter Laurie — also landed a spot on the NOI list, with $92.8 million in revenue on 2.1 million square feet of property.

The REIT temptation

REITs have, of course, been on the rise in the city for the past two decades or so, propelling the likes of Vornado Realty Trust and SL Green Realty to juggernaut status. The two are among the city’s largest commercial landlords, together owning stakes in 67.6 million square feet of Manhattan office space.

Now, some family-run companies are trying to follow in their footsteps.

One of the most notable is Forest City Realty Trust, whose New York division, until recently, bore the name of its founding family: the Ratners.

Siblings Charles, Max, Leonard and Fannye Ratowczer — whose last name was later changed to Ratner — started the company in 1920, after immigrating to the U.S. from Poland.

They earned their reputation first with a building materials company in Ohio but then expanded into retail and prefabricated apartment building development in the 1940s. The company went public in the 1960s — and, in 1985, formed a New York division that was headed up by the founders’ nephew Bruce. He ran the company until 2013 when he turned the steering wheel over to a nonfamily member, MaryAnne Gilmartin.

Roughly three years later, in January 2016, Forest City became a REIT — a move taken to “unleash value in the public markets” and ramp up the firm’s competitive edge in a market filled with public rivals, according to Gilmartin, CEO of Forest City’s New York division.

The Ratner clan relinquished its unchallenged voting control over the company last year. In addition, Bruce and his cousin Charles Ratner announced that they would be stepping down from the company’s board.

The company is now entering a new phase — and with a new name, Forest City New York — focusing less on development and more on investing in market-rate apartments and office properties.

And Forest City is not the only one-time family-run firm to go public recently.

Clipper Equity, founded by Moric Bistricer in the 1950s and currently headed by his son David, also converted into a REIT this year. The move was intended to provide the Brooklyn-based family firm with more access to capital, David Bistricer told TRD when he first announced that the company was going public in 2015. When the company debuted on the New York Stock Exchange this past February, it raised $86 million.

Still, Gilmartin said private companies have the advantage in the development game because they can make “long-game investments” and don’t need to focus as much on quarterly profits.

“We are subject less to the issues around investments from companies here and abroad and more beholden to the public market,” she said.

On the other hand, private companies are often at the mercy of lenders, who they frequently rely on to provide construction financing. For the last few years, the lending spigot has tightened.

And some family firms have changed course as a result.

In 2016, Donald Zucker told TRD that he “finished [his] last building a few years ago.”

Since founding the firm in 1961 as a mortgage brokerage, Zucker has developed nearly 30 rental, co-op, condo and retail buildings.

“I just can’t compete in a marketplace where I can’t make sense of the economics,” said the now-86-year-old.

“I’m not interested in developing condos anymore, because the tax world punishes you terribly. I would do another rental.”

Well-established, family-run firms are basically in the same boat as corporations or REITs in terms of landing financing from banks, which put a high premium on reputation. But the rise of private lenders, which are more open to lending to other types of firms, has increased competition, according to Rosenberg & Estis real estate attorney Richard Sussman.

“Lots of these private lenders aren’t scared about [a borrower] defaulting, because they’ll take over the project if they have to,” Sussman said. “Banks don’t want to do that.”

Public companies may attract a somewhat lower cost of capital than certain private family-led firms, explained George Doerre, who runs one of M&T Bank’s New York City commercial real estate lending teams. That’s largely because those public firms have access to the public markets and, within reason, can issue stock and bonds at will, he said.

Jed Walentas — who heads up Two Trees, which was founded by his dad, David — acknowledged the limits of his company’s structure. His firm bid on the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ iconic Watchtower building in Brooklyn but lost out to Kushner Companies, which paid $340 million and teamed up with the private equity firm CIM Group and LIVWRK.

“We have trouble buying things for a variety of reasons,” he told TRD earlier this year. “We’re quite conservative; we still use all our own money and have no partners. It’s a weird business model — using your own money and being conservative makes you weirdly uncompetitive on things like Jehovah.”

At the same time, private family-run businesses are not obligated to shareholders — a major perk. Most of the companies’ decisions are made by people who have long sat across from each other at the dinner table.

“Bureaucracy is so limited,” said Justin Elghanayan. “It’s me and my father. We’re the decision-makers.”

Other firms, like Related Companies, though it’s private and not a REIT, show the industry’s shift to more corporate-oriented operations.

“Folks like the Related Companies have really figured out how to professionalize the business,” Walentas recently told TRD. “The quality of talent in the business today is totally different than it was even 25 years ago.”

But Walentas noted it’s challenging for family-run companies to attract and retain talent, because high-level employees recognize that boxing out a family member to get a C-suite spot is not likely. Jake Elghanayan said TF Cornerstone has tried to address this issue by allowing employees to invest directly in the developer’s projects.

“It’s tough to get people to buy in when it’s not their family and it’s not their long-term generational assets,” said Anand Bhatia, who works at his father’s company, Bhatia Development Organization, which did not make the ranking. “People might shy away from joining a family business because it’s not going to be theirs someday. They are not going to be CEO.”

The next of kin

The emergence of a second generation can herald major changes for a company.

At Cammeby’s, Avi and Eli filed plans for the company’s first ground-up development project: a massive, mixed-use development in Coney Island.

That was a serious strategy shift from the approach their father had taken. He built the family’s fortune almost exclusively by buying up multifamily properties.

At Two Trees, David Walentas remade Dumbo, transforming it from a world of old warehouses to one of Brooklyn’s priciest residential neighborhood today. But the younger Walentas has shifted gears and has embarked on the massive redevelopment of the 11-acre Domino Sugar refinery in Williamsburg on the Brooklyn waterfront.

And at Wharton, Joseph Sutton has set his sights on the residential sector, acquiring at least three properties last year, Including 275 Bleecker Street in the West Village and 134 Jefferson Street in Bushwick.

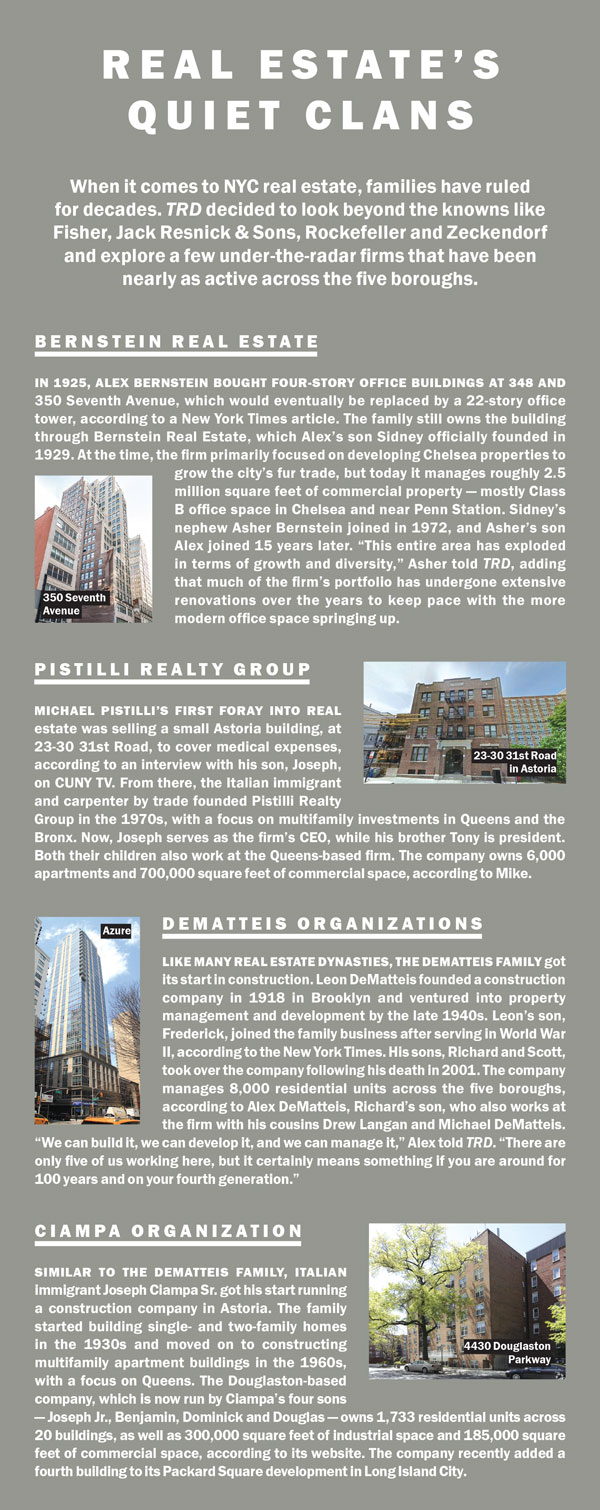

Janice Mac Avoy, who heads Fried Frank’s real estate litigation group and specializes in dealing with family disputes, said priorities commonly shift between the first and second generations. The younger generations are often more willing to take on debt and more risks.

“The first generation is all about amassing their assets and holding onto them forever,” she said. “The second generation might want liquidity.”

Before heading to the White House, Kushner shifted his family company’s focus across the Hudson River to New York City, acquiring trophy Manhattan office buildings like 666 Fifth Avenue and eventually buying up the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ Brooklyn portfolio.

He started young, taking over as CEO in 2008 at 27 years old. He then purchased 666 Fifth for $1.8 billion, setting a record for the most expensive building sale in the U.S. at the time. The purchase, however, was overleveraged, with $1.2 billion in debt. In recent years, mortgage payments on the property have eclipsed the building’s income, and the company has struggled to secure a co-investor, as Bloomberg reported last month.

Now, Kushner’s sister Nicole is getting into the limelight. This past May, she was criticized for playing up her family’s connection to the president in a presentation to potential EB-5 investors in Beijing. She was promoting the firm’s 1,467-unit luxury Jersey City apartment tower, One Journal Square, and touted her older brother’s role in Washington — which, attendees later told Western news outlets, made the pitch more attractive.

But if anything, Jared’s public job has spelled trouble for his family’s company. The firm has come under increased scrutiny, and over the last month federal prosecutors have launched an investigation into the company’s use of the EB-5 program.

But if anything, Jared’s public job has spelled trouble for his family’s company. The firm has come under increased scrutiny, and over the last month federal prosecutors have launched an investigation into the company’s use of the EB-5 program.

For many real estate scions, the family company was not their first professional stop.

Nicole Kushner Meyer spent 10 years at Ralph Lauren until she joined the family firm in 2015.

Joseph Sutton did a stint at Meridian Capital Group before joining his father’s firm in 2014. Justin Elghanayan taught English at a NYC public high school for two years before he joined Rockrose in 2005. Similarly, his cousins Zoe and Jake joined TF Cornerstone after pursuing careers in art management and law, respectively.

Walentas got rejected from journalism jobs at various newspapers, eventually ditching the profession to work for Donald Trump before joining Two Trees.

“It wasn’t a planned or staged thing that I would work there and come to Two Trees,” Walentas said. “[Trump] gave me a ton of responsibility for a kid right out of college with zero experience.”

And not all heirs are eager to follow in their parents’ footsteps.

Bruce Ratner’s daughters both took different routes: Elizabeth works as a journalist, and Rebecca as a filmmaker. Nicole and Jared’s brother, Joshua Kushner, runs his own venture capital firm, Thrive Capital, and their sister, Dara, lives with her husband and their four children in Livingston, N.J.

But even those who aren’t looking to take the reins are likely to inherit assets or stakes in the company.

“Whether you want to work in it or not, it’s yours,” said Andrea Olshan, who took over the position held by her father, Morton, at their eponymous firm. “There’s always that sense of you can go and be whatever you want to be, but [the real estate] is going to be yours and you have to understand it.”

Trouble in paradise

Sometimes the best way to grow is to break up.

At least that was the case for Rockrose, which was founded by Henry, Tom and Frederick. When the Elghanayan brothers split in two in 2009, it was reported that Henry wanted to create a path for his son, Justin, to take over. Justin, however, told TRD last month that the breakup had more to do with the number of second-generation family members working for the company.

“It was going to be hard to have that many next-generation people running the business,” he said.

Splitting up assets is a fairly common for family-run real estate companies grappling with how to pass the baton. Rather than risk disputes between siblings or cousins, the founding members part ways and create separate empires for their progeny to rule. For Rockrose and TF Cornerstone, it’s been successful.

But for the Chetrit brothers, the split was reportedly more acrimonious.

The Chetrit Group split in 2011 amid rumors that the brothers were feuding. Joseph and Meyer kept the original firm’s name, while Jacob and Juda created another entity, the Chetrit Organization.

Joseph’s sons work for the Chetrit Group, though true to their father’s penchant for mystery, their roles aren’t clear. Last year, his son Sam Chetrit told TRD the four brothers each have “very unique” positions.

In general, succession planning can be an ugly topic, which is why it’s often avoided.

“No one wants to hear that there’s going to come a time when they aren’t going to be running their organization,” said Kyle Wissel, a principal at Mazars and a former estate planner. “I think that a lot of people who are really successful, who are on top of the world, aren’t thinking of those things.”

There’s also a human component to why firms don’t discuss the future of its leadership: They don’t want to confronting their leaders’ mortality.

“The phrase is always, ‘If so-and-so dies,’” Mac Avoy said. “They always phrase it as ‘If.’ There is no if. It’s a when.”

At the same time, there’s a great motivator for broaching the subject: Transferring real estate assets from one generation to the next can incur colossal taxes.

One of the most popular ways to curb these transfer taxes is through a so-called grantor retained annuity trust, Wissel said. An irrevocable trust is created for a certain period — during which time a tax and annual annuity are paid. When the trust expires, the asset is transferred to the descendant tax -free.

Still, one of the biggest issues that often goes ignored is finding ways for descendants to get out of the family business. Without an exit mechanism, family members who want to cash out of their stake in a property, for instance, might be subject to a minority discount — meaning they will receive less than their allotted share, or they may be subject to the decisions made by relatives with a controlling interest, Mac Avoy said.

“You might have one person say, ‘You know what, our building is ugly and I want to turn it into the Taj Mahal,’” she said. “Meanwhile, for the family member who’s trying to finance their film career, their distributions have been cut off.”

In addition, for many of New York’s potential “next” generation dynasties, it’s still unclear whether the third generation will ever get in line — largely because that third generation is still in diapers.

Justin Elghanayan, for his part, has 2-year-old twins.

“I don’t know if it’s any indication,” he said, “but they do like making castles out of blocks.”