The year 2000 was big one for Stuyvesant Town. MetLife, the original developers of the massive apartment complex, became a publicly traded company in April that year. By the fall, big changes were in the works – a whopping 58 alteration permits were filed for “replacement of wet walls” throughout the development, covering nearly every building in Stuyvesant Town proper and adjacent Peter Cooper Village.

Since then, Stuy-Town has been sold and defaulted on, surrounded by lawsuits and controversy as successive owners chipped away at rent regulation throughout the complex. Blackstone Group and Ivanhoe Cambridge bought the complex in late 2015 and pledged to keep the 5,000 apartments at the complex affordable for at least 20 years. But throughout the changes in management, at least one thing has stayed constant – year after year, the wet wall replacement permits have been renewed again and again, most recently in December 2017.

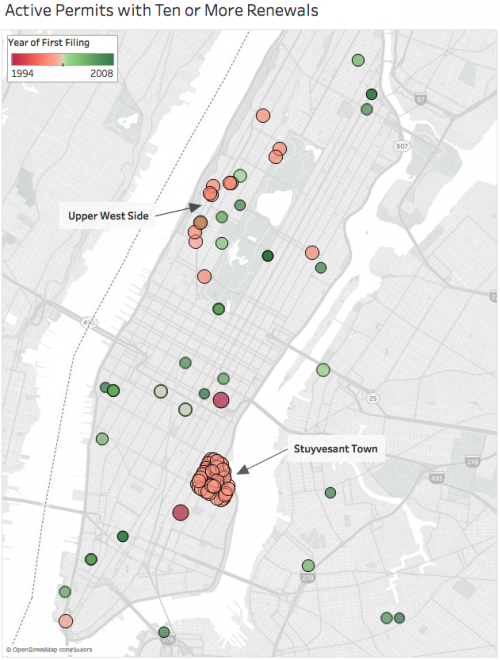

These 58 permits were filed as “ALT2”s – that is, alterations which do not affect the “use, egress, or occupancy” of a building and are therefore considered relatively minor. While the majority of such jobs can be completed within a year, before the first permit expires, altering buildings can often become a complicated task due a variety of complicating factors – as an analysis by The Real Deal discovered, hundreds of ALT2 permits throughout the city have had to be renewed more than 10 times.

“ALT2 jobs shouldn’t take years to complete, but they sometimes can, depending on the scope of work,” said Mercedes Lata, an expediter with S&M Expediting who has been involved with a few long-running ALT2 jobs herself. “Sometimes it’s because the work is large scale, and sometimes it’s because of problems with contractors, where they keep trying to get it completed with different people.”

There are other strange cases of long-running permits throughout the city. The oldest active permit on record was first filed in June 1994, for a “temporary canopy structure in yard” at the Royal Bangladesh Indian Restaurant in the East Village. That permit was renewed for the 23rd time this May.

The Upper West Side is home to several permits from the 1990s, many of which involve landmarked buildings which present their own challenges due to requirements regarding materials. A 1999 permit for the refurbishing of the landmarked Hotel Belleclaire was renewed for the 26th time this April, and 10 other landmarked or otherwise historical buildings in the neighborhood, now home to condominiums and co-ops, have permits dating from that year as well.

All in all, 17 permits that were first filed in the 1990s remain active today, and more than 200 currently-active permits have been renewed 10 times or more. Of course, compared to the total of more than 200,000 A2 permits that are currently active, these are barely a drop in the bucket.

Responsibility for the Stuy-Town “wet wall” permits has changed hands many times, reflecting the complicated recent history of the development itself. After the initial application by MetLife’s director of operations, six other individuals – representing various contractors and management companies – have applied for the renewal of these permits. For the past six years, renewals have been handled by Stuy-Town general counsel Fred Knapp, once known as the “scourge of illegal tenants” when he worked as a private detective for Tishman Speyer.

According to the Department of Buildings, such repeated renewal of permits, though uncommon, is not really a problem. “There is no rule limiting the number of times a permit can be renewed, and there are a variety of reasons a permitted job may take a while to complete,” a department spokesperson said in an email. “Replacement of wet walls can be disruptive as it requires opening up interior walls to access pipes, so the owner may be replacing the walls gradually as apartments turn over so the work can be performed while the unit is vacant.”

However, another source familiar with the matter said that “wet walls” per se weren’t really the point of these permits. “The reality is that it’s a permit that lets them renovate apartments,” the source said. “Stuyvesant Town has over 11,000 apartments, and 4,500 of them remain in their 1947 condition. There was a legacy agreement between the DOB and MetLife, so that instead of having the city overburdened with the permitting process for renovations, they could get renovations done more quickly.”

“Now, that doesn’t mean that they can freely make changes – they still have to get electrical permits, and they’re not able to just change the floor plan or wall condition,” continued the source. “But this just speeds up some of the more standard renovations for those older apartments.”

As confirmed in a previous TRD analysis, many more ALT2 permits have indeed been filed at Stuy-Town in the meantime for more substantial changes.

Check back for part two in this series on ALT2 permits.