Mention the term “millennial” and you may as well run for cover. The generation of young adults who came of age during the financial crisis — and in the glare of social media — is both lauded for embracing innovation and social responsibility and despised for being lazy and self-indulgent.

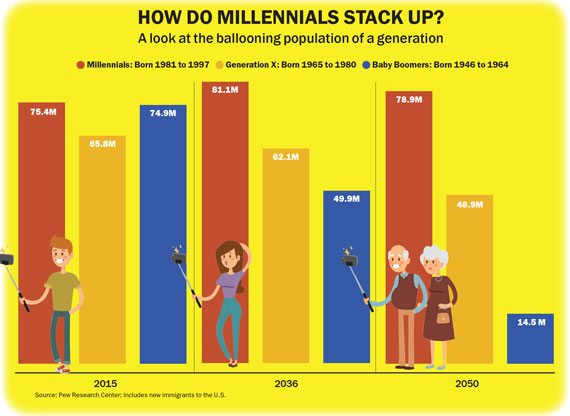

But the sheer numbers make millennials — those born between 1981 and 1997 — all but impossible to ignore.

Currently 75.4 million strong, millennials surpassed the Baby Boomer generation last year, according to the Pew Research Center. One in five New Yorkers is a millennial, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. And their ranks are growing, thanks to an influx of millennial immigrants to the United States.

Their collective spending power is equally enormous. Millennials spend $600 billion a year — an amount expected to balloon to $1.4 trillion by 2020, according to the consulting firm Accenture.

“People are beginning to realize the generation is no longer a bunch of teenagers and college students,” said Morley Winograd, a senior fellow at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School and a co-author of two books on millennials.

The nation’s largest financial firms have already made that realization and are devoting serious resources to slicing and dicing data about millennials. Last spring, Goldman Sachs published a splashy info-graphic on millennials, while PricewaterhouseCoopers began a multi-year study of millennials back in 2007.

And in NYC’s real estate industry, there’s a growing recognition that millennials are impacting everything from residential development to the high-stakes office market to brokerage, retail and hotels.

Of course, the impact of millennials on real estate has to be viewed through the lens of the broader sharing economy that millennials have embraced, as well as their demand for experiences over things, social engagement and — above all else — flexibility.

“If you look at the research on millennials, they’re not making decisions about where they’re going to live in four years. They’re making decisions about where they’re going to live in the next 12 months,” said Ofer Cohen, head of the Brooklyn-based commercial brokerage TerraCRG last month during The Real Deal’s New York Real Estate Showcase and Forum.

That along with their well-documented deferral of marriage, family and home buying — all trends that took off under Generation X — has concerned some industry players.

Earlier this year, Equity Residential Chairman Sam Zell mused: “This whole millennial thing is a bunch of bullshit.”

Speaking at New York University, he said he was “worried about fertility” and delayed marriage among millennials in the context of the nation’s economic growth.

Still, some say there are inherent risks to painting an entire generation with too broad a brush. After all, millennials span a massive economic range — from those saddled with student debt to those raking in millions. And they encompass an equally large age range, from 18 to 34.

“It’s hard to build a real estate product for a [teenager]. You’re thinking about what they want in 15 years,” said Caroline Gleser, director of development at the New York-based BD Hotels, whose Pod hotels are a favorite among millennials.

Appeasing this diverse generation has many real estate executives on their knees. And while developers and landlords are working to get into the millennial mind, some are reluctant to build for one singular demographic.

Appeasing this diverse generation has many real estate executives on their knees. And while developers and landlords are working to get into the millennial mind, some are reluctant to build for one singular demographic.

Michael Rudin, a vice president at Rudin Management, which is teaming up with Boston Properties and office-sharing giant WeWork to develop the Dock72 office building at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, summed it up this way: “We want quality, creative tenants to take the space and hopefully they will bring their workforce — which would most likely be millennials — but we can’t bank on them all being millennials.”

Still there’s no denying that the generation is setting trends for the broader consumer market.

That perspective has pushed BD Hotels to develop products for a certain mindset, rather than an age. “When Pod was conceived, it was something for millennials. [But] what we found is it speaks to the young at heart rather than the actually young,” said Gleser, a 32-year-old millennial.

Below is a look at some of the key areas where millennials are permeating the NYC real estate industry.

Rental development

Despite hype over the condo market, NYC is still a city of renters — and millennials make up a good (and growing) chunk of that population.

With the barrier of entry to buying residential real estate much higher now than it was before the financial crisis in 2008, many New Yorkers (particularly younger ones) have been forced to stay in the rental game. In fact, just 39 percent of millennials nationwide own homes, according to Goldman Sachs — down from 47.5 percent in 2007.

Numbers on millennial homeownership in NYC are hard to come by, but on the whole, homeownership rates here hover around 25 percent, compared to a 64 percent national average.

This fact has not been lost on developers who have geared much of their NYC rental product to millennials — whether it’s extra bike storage (one in five millennials bikes at least once a week, according to the Urban Land Institute), USB charging ports in apartments (two-thirds of millennials don’t have landlines, according to the Centers for Disease Control) or co-working space (nearly one-third of millennials are self-employed, according to a 2015 survey by online stock brokerage TD Ameritrade).

“Millennials are a big chunk of the rental market, so I have to pay attention to what they like and what they don’t like,” said David Maundrell, who recently sold his Brooklyn based-firm Aptsandlofts.com to rental giant Citi Habitats.

While certain amenities clearly appeal to a broad swath of renters, they are prerequisites when trying to lure in younger crowds.

Maundrell is currently marketing several Brooklyn rentals geared toward millennials, including Muss Development and Bedrock Real Estate Partners’ 124-unit 180 Franklin Avenue in Clinton Hill, which has an onsite art gallery and co-working space.

Meanwhile, millennials are the “driving demographic” behind Ironstate Development’s 900-unit rental complex known as Urby Staten Island, said company president David Barry.

The $275 million development, which is located in Staten Island’s Stapleton neighborhood, includes 35,0000 square feet of retail, where Barry envisions seven or eight restaurants and stores. The first phase of the complex is set to be complete this summer and will have an urban garden and communal kitchen, where residents can throw large dinner parties and host events. In addition, the trendy Queens-based Coffeed will operate a café and bodega in the lobby. Ironstate has also hired a chef-in-residence to help residents cook in the communal kitchen, as well as a farmer-in-residence and director of programming. Studios start around $1,600 a month and one-bedrooms are asking $1,900.

Barry said Ironstate spent years fine-tuning its approach to targeting the next generation of renters. In 2011, it launched a 48-unit “test project” in Jersey City. It’s now planning a larger millennial-driven rental project at another Jersey City site along with one in the Bronx.

Even when developers aren’t entirely gearing their projects toward millennials, they cannot afford to ignore them.

Developer and landlord TF Cornerstone, which has a large population of millennial renters, has all but eliminated the paperwork associated with leasing and paying rent — a move designed to appeal to millennials, said executive vice president Sofia Estevez.

Developer and landlord TF Cornerstone, which has a large population of millennial renters, has all but eliminated the paperwork associated with leasing and paying rent — a move designed to appeal to millennials, said executive vice president Sofia Estevez.

It’s also negotiating with Citi Bike to open a station at 4720 Center Boulevard, a Long Island City project, and adding co-working throughout its residential portfolio.

Co-working spaces are — by far — the most popular amenity among millennials, especially those looking to squeeze as much value out of their rent as possible, said Jordan Sachs, CEO of Bold New York.

“It’s not always about finishes and layouts. It’s how developers will be improving their lifestyle,” said the 31-year-old Sachs, whose firm is marketing Sky, the Moinian Group’s 1,175-unit rental tower at 605 West 42nd Street, which offers a co-working space and a slew of other amenities.

At 275 South Street, a 252-unit mixed-income rental building in Lower Manhattan, Nelson Management has added a co-working space, put a keg and iced-coffee machine in the communal lounge and added yoga and kickboxing areas to its fitness center.

“It’s not just for millennials, but let’s face it, they are the trendsetters,” said Robert Nelson, president of the company.

Nelson said he tapped Bold to market 275 South in order to reach young clientele. “I’m 55 years old so I don’t profess to be an expert on what’s happening,” he said. “[Bold] can help usher us to the promised land. Their contemporaries are millennials.”

Residential sales market

Contrary to their reputation, millennials aren’t only renting. NYC’s strong finance, legal and TAMI (technology, advertising, media and information services) sectors have spawned a class of millennial homebuyers.

In fact, more than 100,000 NYC millennials had jobs in law and finance in 2014, according to a recent report from city Comptroller Scott Stringer. And according to real estate giant Zillow, 2.8 percent of NYC millennials earn more than $350,000 — placing them in the top 1 percent of earners here.

Those jobs (and salaries) spell big buying power for some older and wealthier millennials.

“We haven’t seen anything yet. The big upsurge will be in the next couple of years when all those renters turn into buyers,” said Elaine Diratz, senior vice president at Extell Marketing Group, the developer’s in-housing marketing division.

Extell Development is positioning itself for that shift with its 116-unit condo 70 Charlton Street in Hudson Square.

The under-construction building, where one-bedrooms start at $1.6 million, has a 60-foot saltwater pool and outdoor sports court.

The under-construction building, where one-bedrooms start at $1.6 million, has a 60-foot saltwater pool and outdoor sports court.

“It’s a very young, vibrant area, and we wanted to cater to that,” Diratz said.

Nationwide, the 35-and-under set is the largest cohort of homebuyers, according to the National Association of Realtors.

“What’s different between millennials and Gen X is that [millennials] actually have buying power,” said Eric Benaim, CEO of Queens-based brokerage Modern Spaces, citing companies like Google and Facebook that are filled with high-paid millennial workers, as well as entrepreneurs who have their own businesses.

Yet millennials, many of whom entered the workforce during and right after the Great Recession, aren’t all willing (or able) to plunk down millions of dollars for a Manhattan apartment. Many of those millennials are opening up new areas of the city for developers with their willingness to move deeper into the boroughs — as long as there are public transportation and amenities nearby.

In Crown Heights, Pinnacle Group seems to be going after this group of buyers at 382 Eastern Parkway, where one-bedrooms start in the mid-$500,000s. An April launch party had a steam-punk theme, complete with a bourbon tasting and vaudeville performers.

“It’s partly the HGTV and ‘Million Dollar Listing: New York’ effect. We try to tap into that vibe for them,” said Keller Williams NYC’s Sandy Edry, who’s marketing the building.

Bess Freedman, Brown Harris Stevens’ managing director of sales and business development, said millennials aren’t afraid to move to new neighborhoods, particularly if they’re priced out elsewhere. “Millennials take risks in places that they think is going to be a great place,” she said. “The initial investment is a lot less; they can afford it.”

Co-working

There’s no escaping WeWork’s influence on the NYC office market — and no getting around its direct appeal to millennial workers.

The co-working unicorn occupies 2.8 million square feet of space at 30 locations in New York City. And its footprint, both here and elsewhere, is quickly expanding.

At the 675,000-square-foot Dock 72 project, WeWork will lease 222,000 square feet of the building from Rudin and Boston Properties. And the developers are taking a page from WeWork’s playbook for the rest of the building (which will also house co-working space) with a 12,500-square-foot food hall, outdoor game tables and courts and a bike valet.

“Having amenities at your fingertips and within your building is definitely something that the millennial generation has grown up with,” said Rudin, who’s 30. “It’s something they look for.”

But the fact that one third of all millennials are self-employed is the biggest traffic driver for co-working.

And WeWork — launched by 36-year-old Adam Neumann and 41-year-old Miguel McKelvey — is not the only office-sharing company out there.

In all, there’s 5.3 million square feet of Manhattan co-working space, according to Cushman & Wakefield. (Brooklyn has another 1 million.)

While that’s a tiny slice of the office market — Manhattan has 395 million square feet overall — it’s shaking up the way even traditional landlords are thinking. Plus, the co-working space is rapidly growing.

The British company Regus, a corporate version of WeWork, has quietly doubled its space to about 1.5 million square feet at 48 New York locations, according to a 2015 ranking by TRD. And it is now trying to appeal to millennials.

Co-working company Grind recently opened a fourth Manhattan location.

Last year, the company opened SPACES — a “lifestyle-driven” brand — at the Falchi Building, a former Long Island City warehouse. The brand targets “corporate shakers, business nomads, freelancers [and] energetic entrepreneurs,” according to its website, which touts the building’s artisanal food vendors, retail, concierge services and social events.

And WeWork has spawned a slew of competitors.

“We owe WeWork a debt of gratitude for shifting the paradigm of how people view office space,” said Danny Orenstein, a co-founder of Primary, a health-focused co-working company that opened a 25,000-square-foot space at 26 Broadway in the Financial District in May.

Meanwhile, Cowork|rs, which has six locations in New York, is looking to raise $20 million to support its expansion here and across the Northeast. In addition, the Yard added a seventh NYC location in May, leasing a 25,000-square-foot building in Gowanus, while Grind recently opened a fourth Manhattan location, an 18,000-square-foot space in Midtown South.

CEO David Beale said Grind doesn’t target millennials “per se,” but by creating a “cool place to work” it mostly attracts companies that employ millennials.

NYC office market

On the commercial scene, millennials are not just impacting the co-working world. They’re also having a transformative effect on parts of the traditional office market because many of the city’s fastest-growing tenants are creative and tech companies run by 20- and 30-somethings.

The TAMI sectors — which are most often associated with millennials — were responsible for 72 percent of all new Manhattan leases signed during 2016’s first quarter, according to Cushman & Wakefield.

And Brooklyn has seen developers flood in to build office complexes geared to this group. That’s not surprising given that the borough’s population between the ages of 25 and 34 — the older end of the millennial spectrum — has shot up by more than 19.5 percent since 2000, compared to an increase of just 8.4 percent nationwide, according to Cushman.

In Manhattan, millennials have gravitated to areas such as Midtown South, where both co-working companies like WeWork and social media firms like Facebook have shaken up the Class B market.

“We got into this business by basically retrofitting older buildings,” said WeWork President Artie Minson during TRD’s forum last month. “We’ve been able to have a transformational effect on these buildings.”

A new office concept geared towards millennials at 1 World Trade Center

Bruce Mosler, the head of global brokerage at Cushman & Wakefield, said millennials are shifting the geographic boundaries of the office market.

“The whole new workplace strategy, in terms of people gravitating towards the West Side and Midtown South, is driven by a population of millennials, which has now become the largest workforce in the U.S.,” he said. “There’s no arguing with the fact that those areas have seen the fastest rent appreciation as a result.”

In addition, many of the country’s large institutional landlords are devoting manpower to figuring out exactly how to refashion their office spaces with millennials in mind — even if the companies they’re signing are not entirely staffed by members of this much-buzzed-about generation.

For example, Empire State Realty Trust, the owner of the Empire State Building, recently installed a 15,000-square-foot fitness center for tenants in the iconic building’s concourse as part of an effort to reinvent the aging office tower as a modern tech campus for tenants such as LinkedIn and online stock image company Shutterstock.

BD’s Jane Hotel has 50-square-foot, yacht-cabin-themed rooms.

The REIT clearly did its homework. According to Goldman Sachs, 81 percent of millennials say that they exercise regularly, compared to only 61 percent of Baby Boomers.

Meanwhile, real estate giant Vornado Realty Trust recently inked a 250,000-square-foot lease with PricewaterhouseCoopers at 90 Park Avenue after completing a $70 million upgrade designed to appeal to millennials.

In addition to an infrastructure upgrade, the company was “dramatically reimagining the aesthetic of the building to attract … the millennial generation,” said David Greenbaum, president of Vornado’s New York division, during a first quarter earnings call, noting that 80 percent of PwC’s New York workforce are millennials.

Appealing to this younger generation could have major financial implications for commercial players, sources say.

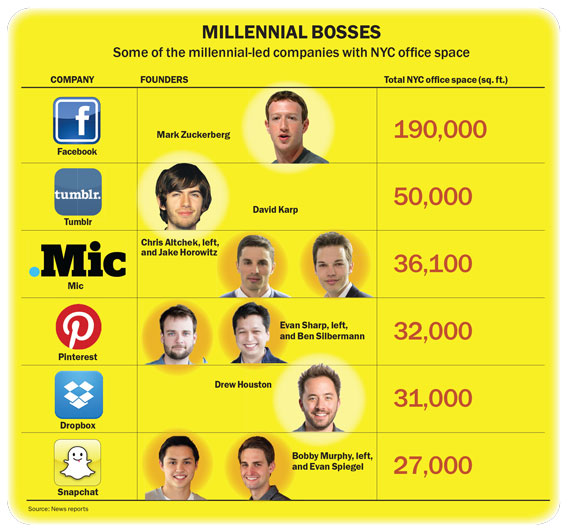

In some cases, office tenants aren’t just courting millennial talent — the CEOs are millennials, too. And they are increasingly factoring in where their employees live when deciding where to ink deals.

“The companies I work for are run by millennials in large part,” said Sacha Zarba, an executive vice president at CBRE who’s found office space for the likes of Pinterest, TED Conferences, eBay and PayPal.

Among the highest-profile millennial-led companies to have signed deals in recent months are Dropbox, which took 31,000 square feet at 50 West 23rd Street, and millennial-friendly news site Mic, which took 36,099 square feet at One World Trade Center.

The Durst Organization, One World Trade Center’s developer, is now capitalizing on the deal. It recently fitted out half the building’s 45th floor as a speculative “creative” work space, with brushed concrete floors, exposed industrial-style ceilings and an open work-space environment.

Asher Abehsera, the CEO of LIVWRK — which along with Kushner Companies and RFR Holding is developing the Dumbo Heights office and retail redevelopment in Brooklyn — said it’s not just creative and tech-focused landlords who need to pay attention to the shifting population dynamics. “C-suite executives and institutions have to understand the ecosystem of this creative culture in order to make deals,” he said.

For many of these millennial-led companies — which often sell goods and services online — a brick-and-mortar office may be their first (and only) shot to establish the look of their brand in the real world, said Amanda Carroll of the architecture firm Gensler, who has helped design spaces for companies such as Etsy, Blue Apron, Vox and Hulu.

Even companies that are operating in traditional office spaces — not in co-working hubs — are following Facebook’s lead and trying to create mini campuses.

In addition, they have embraced the trend of packing more people into smaller spaces and sharing communal amenities like lounges and outdoor space.

By 2017, U.S office spaces will average 151 square feet per worker, according to real estate data provider CoreNet Global, down from 225 square feet in 2010.

By 2017, U.S office spaces will average 151 square feet per worker, according to real estate data provider CoreNet Global, down from 225 square feet in 2010.

In New York, the most recent numbers, which were reported by the city’s Economic Development Corporation, found that the average was 135 square feet in 2013.

To be sure, however, Mosler said it’s silly to think that only millennials want hip, amenity-filled offices. The term, he said, has become something of a catchall.

“‘Millennial’ is a bit of an overused term,” he noted. “There are plenty of us outside that age range that want … to be in the middle of things, to want that level of culture and connectivity in your work environment.”

Hotels

A sprawling suite at the Plaza? For visiting heads of state, yes, but not for millennials.

Amid NYC’s hotel boom — an estimated 6,000 rooms are set to come online this year — millennial travelers are being courted by everyone from the world’s largest hotel chains to operators of upscale hostels and pod hotels, not to mention home-sharing giant Airbnb.

“Hotel companies out there are definitely realizing that the millennial age bracket is increasingly a force to be reckoned with,” said Lauro Ferroni, global head of research for the hotel and hospitality group at commercial brokerage giant JLL.

By 2020, millennials are projected to comprise 50 percent of business travelers, according to a study by the global firm Boston Consulting Group. While a lack of discretionary income may limit this generation’s “leisure” travel, BCG concluded that millennials are twice as likely to travel for pleasure or entertainment than older travelers — and will hunt for deals to fit their budget.

Of course, San Francisco-based Airbnb has changed the landscape for millennials. The company had more than 81,600 apartments listed in NYC as of last month, according to research and consulting firm AirDNA.

Aaron Zifkin, regional director of North America operations at Airbnb, said the experience of staying among locals is appealing to younger travelers.

“Back in the day, showing that you’d made it was all about ownership and people wanted a BMW in the driveway,” he said. “Today, the new currency is experience, having the ability to take a photo somewhere amazing and post it on your social media channels. That’s the new ‘Look at me!’”

In the last 12 months, some hotel companies have even gotten in on the home-sharing action. Hyatt Hotels was part of a group that invested $40 million in Onefinestay, a U.K.-based company that bills itself as an upscale Airbnb.

Meanwhile, major hospitality companies are rolling out millennial-focused brands with smaller rooms, lower prices and trendy bars, such as Marriott’s Moxy, Starwood’s Aloft and Hilton’s Canopy.

In New York, David Lichtenstein’s Lightstone Group said it would invest $2 billion to build Moxy hotels nationwide. Planned New York locations include 105 West 28th Street in Chelsea (343 rooms), 485 Seventh Avenue (618 rooms) and 112-120 East 11th Street in the East Village (300 rooms), as well as a fourth unidentified location.

And, of course, boutique brands have been chasing millennials for several years now.

Samsung’s recently opened Meatpacking District outpost is more of a millennial playground

than a store.

The Ace on West 29th Street, for example, has had a strong millennial following since it opened in 2010 thanks to an art gallery in the lobby, farm-to-table restaurant, coffee bar and event space.

Hotels with micro-sized rooms — and price tags to match — have also been proliferating in recent years.

“Millennials are the purchaser of the future,” said BD Hotels’ Gleser, whose firm has three Pod Hotels under construction (in Williamsburg, Times Square and Washington, D.C.) in addition to the two it operates in Manhattan.

Rooms at the Pod Hotels are around 110 square feet with average nightly rates of $180. Meanwhile, BD’s Jane Hotel has 50-square-foot, yacht-cabin-themed rooms with rates of $99 a night — plus a club that’s regularly open past 2 a.m.

“If you focus on the now and forget the future, you will have a problem down the road,” said Gleser.

Retail

While Baby Boomers still hold most of the country’s wealth, millennials have become the most important demographic for retailers. But they don’t shop like their parents do. And their shopping practices are forcing NYC retail players to rethink the way their stores operate.

Still, millennials are buoying a slew of key retail categories. On one end of the spectrum, they are bolstering health-conscious eateries like Dig Inn and Mulberry & Vine, as well as artisanal restaurants, trendy fitness studios, bike shops and anything with locally sourced foods or materials. On the other, major fashion brands like Uniqlo, H&M and Zara are benefitting from millennial love.

Landlords and retail developers are clearly devoting resources to understanding how millennials think.

BFC Partners, the developer of Staten Island’s new Empire Outlets center, for example, commissioned a research firm, August Partners, to study how millennials feel about outlet malls and fashion in general. The firm found that millennials spend 13 percent more on fashion goods than non-millennials.

Elsewhere, landlords are also coming up with new strategies for curating retailers based on how those tenants will drive traffic to their buildings.

While the pharmacies and banks that dot NYC’s streetscape are not likely to disappear anytime soon, some building owners are making deals with retailers that appeal to millennials rather than locking in traditional credit tenants who might pay a higher dollar per square foot.

At CityPoint in Downtown Brooklyn, for example, developer Acadia Realty Trust could have brought in a bank, but the company’s top brass signed a slew of tiny, homegrown foodie concepts, such as the Arepa Lady, an outpost of a popular food cart known for its South American cornmeal cakes.

“There’s a millennial population moving into Downtown Brooklyn that’s quite demanding,” said Chris Conlon, Acadia’s chief operating officer. “They don’t want the same retailers you see in every suburban model. They don’t want the same places you see in airports. You have to find something more inspiring or you’re going to be in trouble.”

The assumption is that by foregoing the revenue in favor of creating a more dynamic environment, landlords will have a competitive edge when it comes to leasing the office space upstairs to creative companies.

“Many landlords have called me and said, ‘So, I can sign a lease with a retail bank tomorrow but I’m apprehensive about what it will do to the brand of my building,’” Zarba said.

His advice? “If they have the ability to be more selective in terms of who they lease space to, they should.”

But complicating matters (and upending the traditional retail paradigm) is the fact that millennials are more likely to buy online.

Approximately 57 percent of millennials compare prices in stores to what’s available on the Internet, according to a recent study by AIMIA, a Canadian analytics company.

That means retailers have to think outside of the box to attract millennials.

Jason Greenstone, a senior retail leasing associate at Cushman & Wakefield, pointed to Samsung, which recently launched a new Meatpacking District flagship, as an example of a retailer shaking up the traditional mold.

Jason Greenstone, a senior retail leasing associate at Cushman & Wakefield, pointed to Samsung, which recently launched a new Meatpacking District flagship, as an example of a retailer shaking up the traditional mold.

The company’s 55,000-square-foot concept space, which opened in February to great fanfare, is less of a store and more of a digital playground — or even nightclub experience. There’s a virtual reality tunnel where employees can demonstrate Samsung’s virtual reality headset, a Samsung cafe curated by Brooklyn’s Smorgasburg, events spaces where the company can host product announcements, a theater for viewing events like the Oscars and a “selfie station” where visitors can snap photos of themselves that are then projected on a big screen.

But the kicker is that Samsung is not selling anything at the store. Instead, shoppers can test products and then buy them online.

Mens’ fashion brand Bonobos has embraced a similar concept, albeit on a smaller scale. Its “Guide Shop,” which has four NYC locations, including on Fifth Avenue and in Soho, are effectively showrooms where customers can look at clothes and try them on but can’t buy anything. The small but sleek stores — 1,140 square feet at Brookfield Place, for instance — stock all sizes and colors but only have one of each item. Orders can be placed with an employee and shipped for free.

Greenstone said the concept is directly aimed at Bonobos’ largely millennial customer base.

“Millennials are trying to be more efficient in their shopping experience,” he said. “They’re not spending hours in the store anymore. They’re trying stuff on and then ordering it online anyway.”

Co-living

Having roommates is nothing new in NYC, where astronomical rents mean apartment sharing has been the norm long before Silicon Valley deemed it the Next Big Thing.

But now, a wave of co-living startups is edging into the market and targeting the segment of the millennial population who can’t afford to live alone and have embraced a communal mentality.

These operations essentially operate like adult dorms — with shared kitchens, common spaces and, sometimes, bathrooms.

While co-living is clearly in its infancy here, a number of companies are attempting to read the demographic tea leaves.

According to the Brookings Institution, young people are living in cities longer than ever. Not only are millennials delaying marriage and the flight to suburbia, but many can’t afford to leave the city because salaries haven’t rebounded from the 2008 recession. Between 2010 and 2013, only 23,000 young people (ages 25 to 34) left New York — versus 50,000 each year before 2008, the think tank found.

Like they did with co-working, WeWork’s Neumann and McKelvey are leading the way in the co-living world with WeLive, a venture that debuted at Rudin’s 110 Wall Street in April.

The company is aiming to house 34,000 people at 69 locations worldwide by 2018. Membership starts at $1,375 per month, and units range from one- to four-bedrooms, which can sleep up to eight people. For an additional $125, amenities include cable, laundry, Internet and yoga classes.

“We’re not just going to give them the best price, which we will. And we’re not going to just give them flexibility, which we will,” Neumann told Fast Company. “We’re going to give them a social layer of community that has never existed before.”

Meanwhile, Common, a co-living startup with three Brooklyn locations, has raised $7.4 million in venture backing by devising a concept designed to improve on NYC’s existing apartment-sharing reality. (Think pressurized walls and common areas as bedrooms.)

“People are acknowledging that it’s the way people having been living for a long time … we’re just building a product that works for it,” said Brad Hargreaves, the company’s founder and CEO.

And Ollie, another NYC-based co-living startup, is also focused on affordability. “When studios ask $2,500 to $3,000, what you’re saying to the housing market is if you don’t earn $105,000 a year, there’s no place for you,” said CEO Chris Bledsoe.

Ollie’s solution is furnished micro-units and co-living suites along with organized programming and event for residents, ranging from community meals to ski trips. But Bledsoe said while the spaces were designed with young people in mind, he’s since realized the term “millennial” refers to a mindset more than an age.

“We found it’s a general philosophy of people who are rejecting ownership of stuff in favor of acquiring experiences,” said Bledsoe.

Ollie operates co-living suites at a former SRO on West 75th Street, as well as Monadnock Development’s Carmel Place, which has 55 micro-units and shared suites.

Other developers are seizing on the co-living trend, too.

Young Woo & Associates turned the top floor of its rental building at 509 East 87th Street into a communal living space dubbed the Hive, where it rents single bedrooms within three- to five-bedroom apartments.

And Weissman Equities has repositioned a former five-story SRO in East Harlem into an “adult dorm” with five 200-square-foot rooms and shared bathrooms. Rent ranges from $1,200 to $1,500.

Although the project initially targeted “budget-constrained” renters, the building has mostly drawn millennials, said CEO Matthew Weissman.

“They’re more used to a college sort of mentality of living with neighbors in close proximity,” he said. “And they like saving $500 to $1,000 a month on rent; to them, that’s money they can spend on entertainment.”

Of course, co-living has a big upside for landlords.

While data on co-living spaces is hard to come by, landlords can achieve a higher price per foot since bedrooms are smaller than they are in average apartments — even as tenants pay at- or below-market rates for apartments.

The dollars can add up. WeLive expects to generate more than $606 million in revenue in 2018, according to a 2014 investor document leaked last year. At that rate, WeLive will account for nearly 20 percent of WeWork’s total projected revenue of $2.86 billion in 2018.

At 110 Wall, Rudin said he was intrigued by the proposition of WeLive, but he said the deal was also far less expensive than several alternatives Rudin considered, which would have cost the company $200 to $300 million. “The deal with WeWork was around 20-30 percent of that range,” he told TRD in an email.

Residential brokerages

Whether millennials ultimately buy or rent, NYC’s residential brokerages are all fighting for their piece of the “mythical millennial” pie — a term recently coined by the New York Times.

From hiring younger agents to rolling out tech tools to opening offices in emerging neighborhoods, firms are shaking up the status quo to stay relevant in a market where many millennials aren’t convinced they even need a broker.

For example, the 143-year-old Brown Harris Stevens, a firm often associated with blue-blood deals in tony (dare we say stodgy) neighborhoods, is embracing millennials head-on with training programs for young agents and an advisory committee comprised of millennial-aged brokers who share feedback with the firm’s executives.

Based on the group’s recommendations, BHS created a CRM (customer relationship management) system that’s in the process of being rolled out, said CEO Hall Willkie.

Listings and marketing tools can now be accessed via mobile phones, and BHS’ website is adding interactive features, including videos of listings.

“That’s really driven by the younger generation [of agents]; the older generation likes these tools but they’d be perfectly happy without them,” he said.

From Willkie’s standpoint, appeasing millennial agents goes hand in hand with landing millennial clients, since buyers and sellers want to work with brokers they know or can relate to.

“What helps attract agents to us … helps attract millennial buyers and sellers,” he said.

Meanwhile, in May, Platinum Properties launched a “Millennials Guide to Renting in NYC” — geared toward millennial renters with references to HBO’s hit show “Girls” and the Harry Potter book series — to coincide with college graduations and the busy rental season.

Of course, the push to adapt to new customer demands coincides with existing tech challenges facing brokerages. For years, the rise of real estate websites — like Zillow, Redfin and Realtor.com — has forced brokers to come up with new ways to make themselves indispensable.

While the move to these websites cuts across all ages, millennials are more apt than just about anyone else to turn to the web first.

“In many circumstances, they’ve ditched brokers,” said Citi Habitats’ Maundell. “They’re like, ‘What do I need one for?’”

To reclaim those buyers and the next generation of millennials, brokerages are embracing digital advertising, branded content and tech offerings such as video, 3D imaging and collaborative apps.

Robert Reffkin, CEO of tech-focused Compass, said millennials are part of the broader mix of clients the firm is going after.

“We have high-end, Upper East Side clients and young millennials in Brooklyn. They’re equally important,” Reffkin said. “Renters become buyers, and those buyers become future sellers.”

The venture-backed firm — which was recently valued at $800 million — has been rolling out new technologies. In May, it launched a collaborative “Open House App” that auto generates the best route and sequence for viewing apartments, including coffee breaks. The itinerary can be synced with the agent’s and client’s Google calendars.

Doug Perlson, the co-founder of the Flatiron-based RealDirect, a tech-focused real estate brokerage that launched in 2010, said adapting to millennial and other clients just makes good sense.

“Our thesis is you work with buyers and sellers the way they want to work with you. So if you have a group that would rather email or text and never speak to you, that’s fine,” said Perlson. “We’re not going to put a square peg in a round hole.”