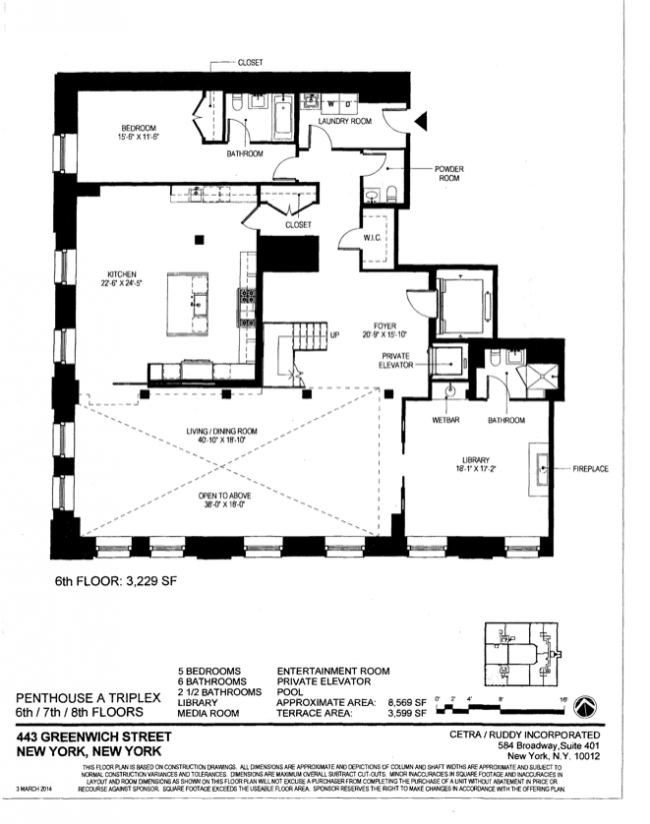

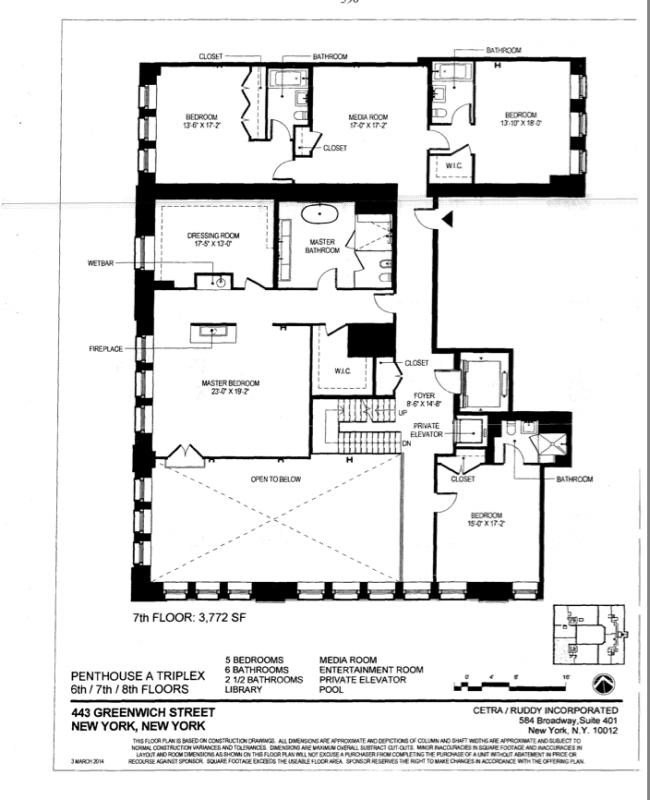

UPDATED, June 13, 1:40 p.m.: Perched atop a 1880s bookbindery with views of One World Trade Center, the sprawling penthouse at 443 Greenwich Street was poised to shatter the city’s Downtown sales record when developer Nathan Berman priced it at $58 million. But when serial entrepreneur Marc Lore closed on the triplex last month for $43.8 million, the Jet.com founder snagged a discount of $14.2 million.

A closer look shows that the 8,569-square-foot condominium didn’t just fall short on price. According to the city’s tax records, Lore’s pad is actually 7,232 square feet — about 15 percent smaller than advertised in the offering plan.

The discrepancy is consistent throughout the building, which Berman’s Metro Loft Management converted into 53 luxury condos in 2014. On average, the usable space in each apartment is 13 percent less than the offering plan states, according to an analysis by The Real Deal and CityRealty.

A difference of 5 percent — and no more than 10 percent — is generally considered to be non-material, according to experts.

Marc Lore’s $44M penthouse at 443 Greenwich

In that regard, 443 Greenwich — a magnet for celebrity buyers like Meg Ryan, Jennifer Lawrence and Harry Styles — sticks out because the difference between the gross and usable square footage is so vast.

One of the most extreme examples is Penthouse D, priced at $21 million. The offering plan’s Schedule A — a table that lists every apartment’s size and price — Penthouse D is described as 5,004 square feet. That’s 19 percent larger than the apartment’s usable square footage on file with the city’s Department of Finance, according to documents.

The building also illustrates a broader dispute in the industry about the “right” way to measure square footage, when there are different standards for sizing up condos, co-ops and townhouses. Calls for uniform standards have grown louder as the market has softened and price-conscious shoppers have increasingly put stock in value, or price per foot. And overstating the size of new condos is just one way developers and marketers may try to tip the scales in their favor; doling out strategic sales updates is another, as The Real Deal has reported.

An attorney for Metro Loft said the offering plan gives buyers “full disclosure” that the units were sold based on the gross square footage, not the usable square footage (which is the more common standard in New York City).

“We make it clear that there are two different numbers,” said John D’Agostino, a founding partner of D’Agostino, Levine, Landesman & Lederman, LLP, which prepared the project’s offering plan. “We fully disclose to the buyers that the gross square footage may not be the same as the usable square footage.”

The discrepancy between the Schedule A and the condo declaration is a function of the building’s original red brick exterior walls, according to Richard Cantor, a co-founder of Cantor Pecorella, which is marketing the project.

If you had an appraiser, a broker and an architect measure an apartment, they’d all come up with different numbers.

“There’s something you’ve got to remember: If you’re dealing with a new high-rise, with glass walls, the exterior of the building and the thickness of the wall is minimal,” he said. “But when you deal with an historic restoration with 18-inch walls, they become part of the space you’re buying.”

Buyers in the building, however, seem mostly unaware that the purchase price reflected the gross square footage — not their usable, or carpetable, space.

“I always thought I had 2,800 square feet,” said one buyer, who asked to remain anonymous. “They sold me 2,800 square feet.”

A second buyer shrugged off the discrepancy, saying that when he re-sells the pad, he will also quote from the offering plan. “The developer isn’t selling [condos] on a price-per-foot basis like meat on a pound,” the second owner said. “So it’s like, this is the price for this unit.”

Lost in space

Loss factor — a term that refers to the difference between rentable area and usable area — is a staple in commercial real estate, where landlords charge tenants for common space. The practice doesn’t often come up in conversations about residential real estate, where there’s little consistency when it comes to measuring the size of apartments and townhouses.

“There really isn’t a universal standard,” said appraiser Jonathan Miller, who uses guidelines established by Fannie Mae and the American National Standards Institute. “If you had an appraiser, a broker and an architect measure an apartment, they’d all come up with different numbers.”

In general, Miller said, co-ops are measured from one inside wall to the opposite inside wall. Condos are generally supposed to be measured the same way, but developers have discovered a certain amount of leeway under the Martin Act, the anti-fraud law championed by Eliot Spitzer as a way to police Wall Street.

Under the Martin Act, developers must secure the New York attorney general’s approval of their plans in order to sell condos. The scope of the law, however, simply requires sufficient disclosures about what’s being sold.

Erica Buckley, a former head of the A.G.’s Real Estate Finance Bureau, said developers are only obligated to disclose their method of measuring units. How they choose to do so is up to them.

Marc Lore’s $44M penthouse at 443 Greenwich

“Since there’s no law that says condos shouldn’t include non-usable square footage, it’s absolutely permissible,” said Buckley, who is now head of a new condo and co-op practice at Nixon Peabody.

She acknowledged the consumer confusion that can cause — particularly when buyers have purchased off the floor plans. “When the apartment is finished and they actually go in, it feels smaller,” she said. “That’s because in some ways it actually is.”

But Buckley and others argued that measuring gross square footage makes the most sense.

“When you buy a house, you buy the walls and roof,” said Stephen Kliegerman, president of Terra Development Marketing. “So when you buy a condo, it’s the same thing.”

Unlike buying a condo — which is considered real property that can be bought and sold — co-op buyers are purchasing shares in a corporation that owns the building.

“In a co-op, you don’t technically own the floors or walls. You pay maintenance, which is essentially rent,” said Warburg Realty’s Jason Haber.

That inconsistency can create problems in a market where buyers and sellers have grown accustomed to accessing data online and determining value on a per foot basis.

“For a consumer to get a sense of what they’re willing to pay, you need to make apples to apples comparisons in the market,” Miller said. “Most people will default to assume that they’re all the same and they’re not.”

Buyers today want relative value, no matter the sticker price, said Douglas Elliman’s Frances Katzen. “The price per foot is a barometer for a prospective buyer as to whether they’re getting value,” she said. “It also impacts the long-term usability and salability.”

Banks also appraise residential real estate based on comparative value. “If your apartment is not 10,000 square feet, and it’s 7,000 square feet, that’s not good,” said one broker. “Your comps are not predicated on accuracy.”

Suing over size

Over the past 20 years, a number of peeved buyers have sued over smaller-than-advertised condos and co-ops.

Many residential brokers cite a 1998 case that became a turning point for the industry. That’s when the buyers of a $2.5 million Park Avenue apartment sued Stribling & Associates, upon discovering the 3,300-square-foot pad they purchased was only 2,850 square feet.

Within a year, the city’s major residential firms stopped including square footage on show sheets or printed materials to avoid the threat of litigation.

In recent years, buyers have been able to negotiate discounts with sellers when they discovered a material discrepancy. In 2013, prom dress retailer David Wilkenfeld sued the seller of his $13 million penthouse at 200 Chambers Street after discovering the pad was about 150 less than what was stated in the offering plan. The parties ultimately settled.

Basement show

Measuring townhouses — where gross square footage is the norm and below-grade space isn’t included — might be the messiest of them all.

According to a 2017 analysis by Olshan Realty, the vast majority of townhouse listings overstate the square footage listed in city records.

The study, which compared 162 townhouses on the market in May 2017, found that nearly three-quarters of the properties were smaller than advertised. Of the 162 townhouses for sale at the time of the study, 34 of them — or 21 percent — were described in excess of the property’s FAR (floor area ratio).

“It was crazy,” said the firm’s founder, Donna Olshan. “In townhouses, you’re not supposed to count the basement, but many brokers do.”

When the apartment is finished and they actually go in, it feels smaller. That’s because in some ways it actually is.

Compass president Leonard Steinberg questioned the veracity of excluding basements from official measurements. “If you can walk on it, it’s square footage,” he said. “It’s up to the agent to break it down to buyers as to what’s usable or less usable.”

Steinberg — along with several other agents — have been working quietly to challenge the status quo.

Over the past few months, a group of brokers met several times to lay the groundwork for a new organization that would tackle issues like ethics and professionalism in the industry. High on the nascent group’s list of priorities is establishing a standard way to measure residential units.

Leonard Steinberg

“It’s something that’s been neglected for far too long,” said Steinberg, who is involved in the group but emphasized that he’s not the spokesperson. “So many people value by dollar per foot — and there’s no uniformity.”

Co-ops in particular have put themselves at a disadvantage, according to Steinberg, because they rely on room count versus square footage — thereby downplaying their relative value compared to condos.

For that reason, he believes units should be measured by gross square footage, not usable square footage.

“Tape measures exist for a reason,” he said. “We didn’t build buildings with spandex. There’s a gross square footage to every structure in New York City and they can be measured — and they should be.”