The New York City Housing Authority’s Shola Olatoye has aggressively pushed for more face time with Ben Carson — the conservative HUD secretary and onetime presidential candidate who warned against making public housing too “comfortable.”

The two met once at Carson’s office in Washington, D.C., a few weeks after his appointment, and later at an informal breakfast organized by a community church.

But the retired neurosurgeon has yet to visit a NYCHA housing project, and as diplomatic as the agency’s chair and CEO tries to sound, the sting is noticeable.

“Having some policy guidance and direction to public housing authorities about what you’re interested in, or even just a welcome letter like ‘Hey, I’m Ben,’ would be kind of nice,” Olatoye told The Real Deal this summer as she gave a tour of a vegetable farm at Howard Houses, a notorious project in Brownsville, Brooklyn.

“Any businessperson will tell you that you look at your biggest liabilities, your biggest cost centers,” the former HSBC executive said. “We are your biggest cost center.”

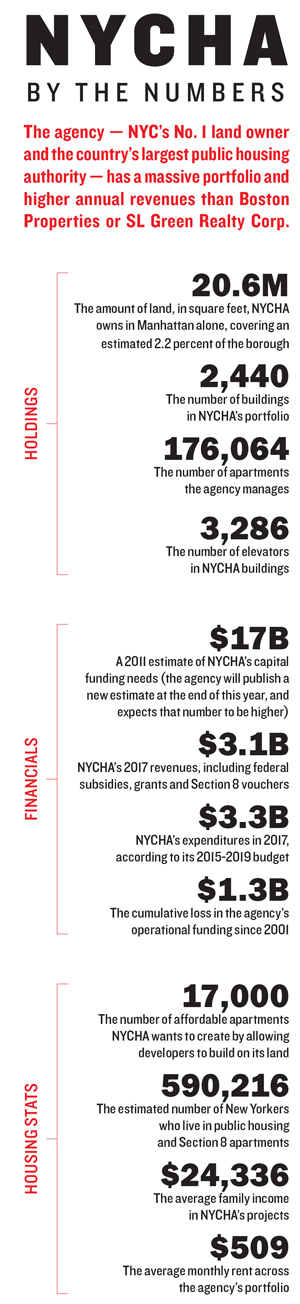

It’s been an exceptionally tough year for the city’s biggest residential landlord, which is contending with a $17 billion capital shortfall. NYCHA oversees 2,440 buildings and 176,064 apartments in the five boroughs that an estimated 600,000 New Yorkers call home. And it depends on the federal government for more than 60 percent of its funding.

Now, with the Trump administration threatening crippling cuts to its funding, the agency is becoming increasingly reliant on the city’s real estate industry as it tries to keep itself afloat. Under a 10-year plan that launched in 2015, NYCHA is partnering with private developers, leasing some of its buildings to Section 8 landlords and working with the commercial brokerage giant Cushman & Wakefield to overhaul its offices — all in a bid to plug the gaping hole in its budget.

Now, with the Trump administration threatening crippling cuts to its funding, the agency is becoming increasingly reliant on the city’s real estate industry as it tries to keep itself afloat. Under a 10-year plan that launched in 2015, NYCHA is partnering with private developers, leasing some of its buildings to Section 8 landlords and working with the commercial brokerage giant Cushman & Wakefield to overhaul its offices — all in a bid to plug the gaping hole in its budget.

As the plan picked up steam this year, it ran into fierce opposition in many cases. But observers say it may be the agency’s best shot.

“The only way that they’re going to resolve their issues is to partner with outside sources,” said Todd Gomez, who heads Bank of America’s affordable housing lending business in the Northeast. He added that the government “doesn’t have the will” to give NYCHA the money it needs.

Aaron Koffman, a principal at the affordable housing developer Hudson Companies, meanwhile, scoffed at the funds Albany agreed to give to the agency under its annual budget in April. “To be frank, hearing the state Legislature celebrate allocating $200 million to NYCHA when the need is $17 billion and rising — these are the challenges [the agency is] facing,” he said.

Olatoye and Mayor Bill de Blasio had to look to the real estate industry and broader private sector “to help offset some of these challenges,” Koffman noted.

New allies

Peter Hennessy, an executive vice chairman at Cushman, gave a presentation to NYCHA’s top brass in late 2016. The focus was how the agency could save millions by using its office space more efficiently.

About half a year later, NYCHA announced that it would vacate its headquarters at 250 Broadway and move employees to its other office at 90 Church Street — shrinking its footprint by nearly 25 percent to 1 million square feet by the end of 2019. The hope is that the office restructuring will save the agency $26 million a year starting in 2024. “It’s a giant jigsaw puzzle,” Hennessy said.

But the next three years may prove to be a defining time for NYCHA’s broader 10-year plan, dubbed Next Generation. Among the many initiatives, the agency is converting a handful of its properties into Section 8 housing, which grants rental assistance for low- and moderate-income families. To do that, NYCHA has been leasing those buildings to private landlords and developers and helping secure federal rental vouchers for its tenants. The move essentially shifts residents out of publicly owned housing and reduces the agency’s tenant load, which helps lower its overhead.

In June, the agency announced $560 million in public and private investments in the 1,395-unit Ocean Bay housing complex in Far Rockaway, a NYCHA project that MDG Design + Construction and Wavecrest Management will oversee as Section 8 housing going forward. Meanwhile, the agency is looking for sponsors to convert another 1,700 public apartments scattered across Brooklyn and the Bronx.

Olatoye explained that the Section 8 program has been more immune to budget cuts than NYCHA in the past, while private landlords can take out mortgages to pay for capital improvements — something NYCHA is prohibited from doing as a public agency. Hudson’s Koffman pointed to a second benefit: While the agency needs to take care of more than 170,000 apartments, a private landlord has far fewer and can pay more attention to them. “It’s almost like the best kind of micromanagement,” he said.

NYCHA’s other big push is leasing out land to developers to pave the way for new affordable and mixed-income rental properties. The agency hopes to create 10,000 units in 100 percent below-market-rate buildings by 2025, and another 7,000 affordable units in buildings where half the units are market rate and the other half are below market.

Last year, NYCHA tapped developers for the construction of fully affordable projects at two public housing sites — a $78 million rental building at the Ingersoll Houses in Fort Greene and a $40 million building next to Crotona Park in the Bronx. Both will provide housing for LGBT seniors, developed and managed by the nonprofit SAGE in partnership with Don Capoccia’s BFC Partners and the homeless services provider HELP USA.

The housing agency has also issued a request for proposals to build fully affordable buildings at the Harborview Terrace, Sumner Houses, Morrisania Air Rights and Twin Parks West NYCHA developments in Manhattan, Brooklyn and the Bronx. No developers have been tapped for those sites yet.

Meanwhile, the sites that are being allotted for mixed-income apartments would generate more revenue for NYCHA because the agency can lease the land at a higher price.

Olatoye and her colleagues are currently reviewing proposals from developers to build near the Wyckoff Gardens complex in Boerum Hill and have picked LaGuardia Houses in the Lower East Side as the next site to market. And in October, NYCHA announced that it is seeking to partner with a private developer for a mixed-income rental property at Cooper Park Houses in East Williamsburg, where land prices have spiked in recent years.

But developers who looked at some of the sites told TRD that mixed-income projects tend to be far more competitive, since they attract market-rate firms in addition to the usual affordable housing specialists. NYCHA also typically demands annual ground-lease payments upfront along with an ownership stake in the project.

The upfront rent payment discouraged Hudson from submitting a proposal for the Wyckoff development, Koffman said. “When there’s major cost overruns, it’s really hard to make the project work,” he noted.

Local tensions

Competition aside, the mixed-income developments also tend to be far more controversial among residents and public advocates, adding to the difficulties.

“You have to know what you’re getting yourself into,” said Jordan Barowitz, who heads public affairs for the Durst Organization. Building on NYCHA land, he said, tends to be more complicated than building elsewhere in the city due to the many political issues involved.

For an example, look no further than Holmes Towers on the Upper East Side. In May, NYCHA tapped luxury developer Fetner Properties — whose other projects include the condo development 1212 Fifth Avenue, where prices go as high as $12 million — to build a 47-story rental tower over a plot of land at the housing complex on a 99-year lease. Half of the tower’s units will be market rate, while the other half will be below market. Fetner paid the agency $25 million for the land as well as rights to develop a 350,000-square-foot building.

But residents at the housing complex immediately pounced on the deal, complaining that the new tower would wipe out a playground, while city politicians warned that placing market-rate apartments in the middle of a housing project would be a cruel juxtaposition of wealth and poverty.

Local City Council member Ben Kallos claimed Fetner plans to cluster the affordable apartments on lower floors and reserve the upper flowers for higher-paying tenants. But representatives for Fetner and NYCHA deny that.

Kallos said he would support the infill program only if it was fully affordable and argued that the $25 million Fetner paid the agency for the land was far too low. “It would be a violation of anyone’s fiduciary duty at a company to sell off all of your assets, leaving you without the money you need to maintain your existing properties and no plan to get out of it,” he said. “There are some apartments in my district that cost $25 million,” the council member added.

Joel Bergstein, president of the New Jersey-based real estate company Lincoln Equities, noted that when his firm cut a deal with NYCHA to build on public land at Hallets Point, Queens, under the Bloomberg administration, all the money was earmarked for improvements at the local housing project. If payments flow into NYCHA’s general fund, he argued, public housing residents are more likely to oppose a private development next door.

“Residents need to see that the money actually benefits them,” he said.

Unlike with the Hallets Point deal, NYCHA now allots 50 percent of ground lease payments to that housing complex, and the other half to the agency’s general fund — which pays for the upkeep of its buildings across the city.

Deborah Goddard, NYCHA’s interim real estate head, said it would be unfair to spend all proceeds from a ground lease sale on the surrounding project, since that would leave other complexes that don’t have land suitable for development starved of funds.

Slow progress has been another issue. By next June, when the Holmes Towers deal with Fetner is expected to close, two and half years will have passed since the agency first began talking to residents about the site.

“I think the housing authority may have been a little bit unaware of the depth of the resident engagement that was necessary,” Goddard said, adding that she expects the program to pick up speed soon. “Once we get our first 50/50 [affordable and market-rate property] under our belt, things will get easier,” she said. The agency’s goal is to announce two new developments per year.

Ron Moelis, co-founder of the affordable housing developer L+M Development Partners, said taking things slow at the beginning may not be such a bad idea. “I think it’s important that they get it right with the first sites that they roll out,” he said. “If [NYCHA residents] start to see real benefits from the program, they may be more open to supporting it.”

Some observers, however, are fundamentally skeptical of NYCHA partnering with private developers. “The problem of public-private partnerships is that they create a system where risks get offloaded on the public,” said Elvin Wyly, a geographer at the University of British Columbia who has studied New York public housing. For example, if developers do a poor job managing NYCHA buildings under a lease deal, the agency would be left with the fallout, he noted.

NYCHA uses a chunk of land at Brooklyn’s Howard Houses for a small farm where residents can pick up produce in return for helping plant crops and drop off food scraps to compost. But some argue that land would be better used for a new public-private development. (Photo by Sasha Maslov)

And Stewart Sterk, director of the center for real estate law and policy at Cardozo School of Law, argued that raising money through private development is easier said than done. “I think it’s a great idea, but it’s a drop in the bucket,” he said. “I just don’t think that the funds they hope will be there will be there.”

Harsh realities

The need to upgrade the 83-year-old agency’s housing stock is hardly new, but it has intensified over the years. Most project buildings in the city were constructed in the 1940s and ‘50s, and more than 75 percent of them are over 40 years old, according to the Center for an Urban Future. As those properties continue to age, their maintenance needs become greater.

Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg appointed Wall Street veteran John Rhea in 2009 to shake up the agency and prevent its properties from falling further into disrepair. Rhea launched an ambitious program to bring in private investors, signing a deal with Citigroup that gave the bank housing-tax credits in return for lining up $230 million in investments in city-built housing. But he resigned in December 2013 amid reports that he sat on $45 million in city funds to install security cameras for years and was slow to spend $1 billion in federal money.

De Blasio appointed Olatoye to head NYCHA in February 2014, a month after he took office. Olatoye joined the agency from the affordable housing nonprofit Enterprise Community Partners, where she had been working as a vice president and market leader for the organization’s New York office.

The mother of three — who grew up in the industrial Connecticut city of Waterbury and whose grandmother lived in Albany Houses in East New York — started her career working for education policy organizations. In 2001, she joined the real estate consulting firm HR&A Advisors, where she worked for six years before joining’s HSBC’s community development group.

Olatoye and de Blasio unveiled their Next Generation plan in May 2015 with the city promising to spend more on public housing to help make up for federal funding shortfalls. At the same time, the agency said it would save $90 million a year by streamlining its operations and another $30 million by improving rent collection.

But just as the plan began making inroads in late 2016, NYCHA got a curveball: Donald Trump’s surprise election victory. In March, after Trump proposed a preliminary federal budget that would slash the agency’s operations funding by $75 million this year, Olatoye told City Council members that “we face the most uncertain times in public housing history.”

Bronx council member and Committee on Public Housing Chair Ritchie Torres was even more direct and said the Trump administration “poses the gravest threat to public housing” in NYCHA’s 83 years.

In May, the White House released a budget for the fiscal year 2018 that would cut NYCHA’s capital funding by more than $200 million and its operations budget by $165 million per year, according to the city comptroller Scott Stringer. The proposed cuts have yet to become law, as Congress was negotiating over a budget bill at the time of writing.

But NYCHA has been struggling with neglect and budget cuts for decades. The flow of money the agency receives from Washington has been drying up since the 1980s as budget hawks in Congress have slashed HUD’s funding time and time again. Between 2001 and 2014, the agency lost $1.16 billion in federal funding, according to a 2015 report by the City Council.

Olatoye said she does not know if Carson — who famously called poverty “a state of mind” — recognizes the challenges that NYCHA faces and whether he has a plan to address them. “We’ll have to wait and see,” she said. “Until then, there’s sort of a tabula rasa.”

But the news from Washington can’t be encouraging. The neurosurgeon-turned-author hesitated to take the job last year because he claimed to lack the necessary experience. Carson reportedly accepted out of a sense of duty to country and because he thinks an outsider can change the agency for the better.

And his failure to stop the White House from proposing $6 billion in cuts to HUD’s budget is telling: Carson has a conservative’s skepticism of entitlements, including public housing. In May, he told the New York Times that good social housing policy is making sure to not create “a comfortable setting that would make somebody want to say: ‘I’ll just stay here. They will take care of me.’”

HUD’s New York point person — who is tasked with overseeing the department’s operations in the country’s biggest city — is Lynne Patton, a former Trump Organization employee. Patton made a name for herself by helping organize Eric Trump’s wedding and sitting on the board of his namesake foundation.

Sources say that unlike Carson, she has taken steps to understand NYCHA’s mission. But while Patton has met with Olatoye and several of the agency’s stakeholders, her vision for public housing in New York remains unclear. A HUD spokesperson said Patton is still “acclimating to her new role” and declined to set up an interview. Carson was also not made available for an interview for this story.

The HUD secretary “cares deeply about people, and that’s refreshing and important,” Olatoye said. “But someone on that team needs to be able to talk about the physical and financial infrastructure that we’re managing. We haven’t seen that yet.”

Torres said he has little faith things will change for the better. “The irony is that you have two people who are ideologically hostile to the agency they lead,” he said about Carson and Patton. “Do I trust that a right-wing ideologue is going to protect the social safety net in New York City? No.”

Permanent fixes?

No one expects NYCHA’s 10-year plan to solve all its funding problems — especially if federal budget cuts become a reality. This leaves the agency with two options for the time being: embark on a more radical plan to raise money and cut costs or soldier on in hopes that one day a more sympathetic Congress will grant the cash it needs.

Howard Husock, of the conservative think tank Manhattan Institute, advocates for the former. He said that while he supports the Section 8 conversion program, it “is not going to be a new spigot of federal funds that will bail out the system.”

Instead, Husock insisted that NYCHA should end the practice of tying rent to income and limit the time any household can spend in a public housing apartment to five years. He said the agency also needs to double down on raising money from the private sector.

Rather than just lease underused land to developers, Husock argued that NYCHA should sell off entire developments in pricey neighborhoods like Chelsea and use the proceeds to plug the hole in its budget.

NYCHA owns 25 properties in the Lower East Side and East Village, 15 on the Upper West Side and four in Chelsea. This year, the city assessed the agency’s Chelsea-Elliot Houses between 25th and 27th streets and Ninth and 10th avenues at $323.7 million, up from $244.9 million in 2014, property records show. The true market value is likely much higher.

But the complex is also home to more than 2,000 low-income New Yorkers, and housing advocates and politicians balk at Husock’s premise that NYCHA needs to shrink to survive.

“I philosophically object to the sale of public housing land,” Torres said. “The object of the city should not be to generate quick revenue, it should be to create a stock of permanently and deeply affordable housing that can be passed from one generation to the next.”

Some real estate players say the agency should stick with its current program but pick up the pace. “They should do more infill,” the Durst Organization’s Barowitz said, noting that dozens of NYCHA sites would be suitable for development. “A lack of density is one resource they have in abundance,” he added.

But Goddard cautioned that there’s a limit to how many public-private developments the agency can get into at any given time. Holding numerous meetings with residents, printing flyers, preparing requests for proposals and negotiating with developers is time-consuming, she said. And affordable housing developments on NYCHA land depend on state-backed tax-exempt bonds, which have an annual cap.

Several observers argue that while private capital helps, the agency’s salvation can only come from public coffers. “It’s not a broken model, it’s a broken funding promise from the federal government,” said Rachel Fee of the New York Housing Conference.

In the past, public housing advocates have struggled to get voters, and by extension politicians, on their side. The isolated designs of NYCHA’s projects, which look like small cities and are often removed from the street grid, don’t help. “For most city residents, public housing is out of sight and out of mind,” Husock said.

But this year’s proposed HUD cuts were so draconian they jolted even those who don’t normally think about public housing — a potential silver lining for the agency, according to Goddard and others. A growing number of politicians and advocates are now aware of what’s at stake for New York’s public housing stock and are willing to fight for it.

“NYCHA was teetering on the precipice well before the Trump presidency,” Torres said. “In 2017, the agency is in a struggle for survival.”