In late March, developer Ben Shaoul arrived at his Upper East Side luxury condo project and began inspecting a model unit. That very week, the Paris Forino-designed apartment at 389 East 89th Street was slated to make its debut to prospective buyers. The goal would be to sell all 156 units by the end of the year. To most naked eyes, the surroundings, which featured custom Italian cabinetry and a plush purple velvet settee, looked flawless. But Shaoul immediately spotted a minor chip in the paintwork on the doorframe. In between swigging gulps of Diet Coke and barking on his cell phone, he chewed out the construction workers.

It was 9:30 a.m., and the 39-year-old property mogul behind Magnum Real Estate Group was already fired up.

“I just had my breakfast, which is like my lunch because I’ve been up so long,” he said, sinking into an armchair between calls.

He noted that he needs only five hours of sleep. After that, he said, “it’s depreciating returns.”

Shaoul, who quit college at 19 to go into real estate, has the reputation of being one of the most hard-driving players in the industry. Those who have done business with him describe him as down-to-earth yet difficult to work with. Bloggers still love to call him “Sledgehammer Shaoul,” a reference to his days as a landlord of rent-regulated tenants. And, two years ago, his own parents, first-generation Iranian Jews who ran a wholesale antiques business, sued him for allegedly cheating them out of money owed on properties they owned together. The two parties eventually settled out of court.

Shaoul, who has called these attacks unfair, is sensitive to what is said about him.

“You had better not write something bad about me,” he told this reporter. “If you do, it will be the last time we talk.”

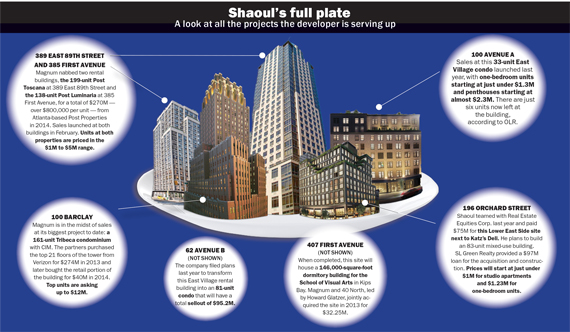

These days, however, the buzz surrounding Shaoul is more about his output than his controversies. At a time when many NYC developers are sitting on the sidelines amid mounting concerns about a real estate bubble, he is firing on all cylinders. A workaholic, he’s always had his hands in many projects. But he’s never juggled so many sizable projects at once. Over the past five years, he has scaled the ranks from a smalltime landlord to one of the city’s most important developers, partnering with major institutional capital providers and taking on ever more challenging and risky projects. His portfolio includes retail properties, condos, rentals and even dormitories. All told, he said his holdings are valued at more than $3 billion. In Manhattan, he currently has close to 500 new condo units on the market, which is likely more than any other developer right now.

“His growth is pretty wild. He’s a beast in the marketplace and he is able to do things that other people can’t,” said Ryan Serhant of Nest Seekers, who is marketing Magnum’s condo project at 100 Avenue A. “I don’t know of another single developer who has as much going on as he has.”

Of his four condo projects on the market, three are mid-market, with units ranging from under $1 million to more than $5 million. The most high-end — and Shaoul’s biggest project to date — is 100 Barclay, a $915 million conversion, in partnership with LA-based CIM Group, of the former Verizon building at 140 West Street. In 2013, Shaoul purchased the top 24 floors and later the ground-floor retail portion for more than a combined $300 million. Just last year, he and CIM secured a $390 million loan from New York- based iStar Financial and Connecticut-based H/2 Capital to convert the building. It’s the biggest loan Shaoul has ever taken.

Of his four condo projects on the market, three are mid-market, with units ranging from under $1 million to more than $5 million. The most high-end — and Shaoul’s biggest project to date — is 100 Barclay, a $915 million conversion, in partnership with LA-based CIM Group, of the former Verizon building at 140 West Street. In 2013, Shaoul purchased the top 24 floors and later the ground-floor retail portion for more than a combined $300 million. Just last year, he and CIM secured a $390 million loan from New York- based iStar Financial and Connecticut-based H/2 Capital to convert the building. It’s the biggest loan Shaoul has ever taken.

Units at the 161-unit building are asking up to $12 million apiece at the top end and the New York Post reported that Shaoul is seeking to fetch $105 million for the penthouse. (Shaoul said no price has been determined.) Sources said 100 Barclay will be the true test of how far he’s come and how well he can deliver on a large scale.

But in a city where developers often prefer to focus on just a couple of asset classes and churn out one or two projects at a time, Shaoul is a firm believer in diversification. He owns a myriad of small multi-family and retail properties all over the city, including 400,000 square feet of retail currently for lease at 140 West Street. He is also developing a dormitory for the School of Visual Arts in Kips Bay.

“Sometimes you want to eat pizza and sometimes you want to eat burgers,” he said. “When one sector isn’t performing well, other ones could be performing better. In the recession, when Lehman wasn’t funding my projects, I leaned on my multi-family stuff to plug a hole of debt that wasn’t available.”

As evidence of his wide-ranging strategy, in January, he snapped up a six-story Soho multi-family building at 6 Greene Street for $24 million, a drop in the bucket compared to the hundreds of millions his condo projects are valued at.

“People say, ‘Why do you still do smaller deals?’” he said. “But why shouldn’t I? I like small deals and I like big deals. You don’t have to just do big deals to make a name for yourself or make money. Sometimes a small deal performs better than a big deal.”

Build fast, sell fast

If there’s another often-used word in Shaoul’s playbook, it’s “velocity.” Along with his East 89th Street project, he is also looking to sell out the 138-unit Luminaire in Gramercy, all under the assumption that the units will hit a sweet spot in the under-$3-million market. As a result, while many New York developers might elect to wait and take advantage of patient capital to eke out the last dollar for investors, Shaoul takes a quick and dirty approach to sales.

“His idea was to build fast, sell fast and make a respectable margin,” said James Lansill of Corcoran Sunshine, the brokerage firm marketing the units at East 89th Street. “That was precisely what intrigued me about working with him. He had this sort of counterintuitive strategy. He said he’d be very happy if we sold the whole building out in a couple of months.”

Shaoul bought the East 89th Street building for $800 per square foot and poured additional funds into the conversion. He is now aiming to sell those units for just $1,300 per square foot, at the low end of the price spectrum. By normal standards, that’s as tight a margin as you see in today’s market, sources said.

For Shaoul, it’s a no-brainer.

“If you sit back and actually do the math, there’s no reason to sit there and wait for the last nickel,” he said. “Let the buyer feel like he got something. Just sell them and move on to the next one.”

He explained that he can widen his profit margin by selling by the end of the year, which allows him to avoid six months of additional carrying costs— interest on loans, taxes, marketing fees, etc. — which he initially factored into his budget.

“Our business model has always been to deliver a little bit more and charge a little bit less,” he added. “If I’ve sold you an apartment for a few dollars less, I’m making that back on the back end.”

Still, he declined to comment on exactly how many units he’s sold at his projects, except to say that sales of apartments in the $1 million to $3 million range were “unbelievable.”

“I’ve never sold apartments like this in my life,” he said.

In contrast, the pace of sales at 100 Barclay has been considerably slower. Less than 70 of the building’s 161 units are now in contract after 14 months on the market, according to listings service Online Residential. (Shaoul disputed that figure but declined to provide the actual number of units in contract.) The property, designed by Ralph Walker, recently received its first temporary certificate of occupancy, meaning move-ins can begin for some of the units.

It’s no secret that uber-luxury condo sales have slowed considerably since 2015. Manhattan properties priced at $4 million or more sat on the market for an average of 275 days in the first 25 weeks of the year, according to data from Olshan Realty. That’s compared to a marketing time of 233 days during the same period last year.

But Shaoul isn’t willing to acquiesce to a weak market. In a bid to spur sales, he earlier this year replaced the Douglas Elliman marketing team for 100 Barclay with another team from Corcoran Sunshine. The $915 million project had comprised a large chunk of the $6.2 billion in total new development listings marketed by Elliman at the time.

Shaoul said the swap wasn’t a reflection of Elliman’s performance or a sign of slow sales at the building. Rather, he wanted some fresh marketing ideas as the conversion approached completion, he said.

Along those lines, brokers say working with Shaoul can be challenging, especially when he’s dissatisfied.

“Going to a meeting with him is like playing tennis. You know you’re going to have a good, intense game,” Lansill said. “He elevates the game by bringing intensity into the room. He knows when there’s a weak link and he’ll call them out on it.”

Leonard Steinberg, the president of Compass, which is marketing Luminaire, agreed. “No one has ever described Ben as shy and no one ever will,” he said. “But he’s a New York developer and he has an audience here in New York. People here appreciate a bold, honest opinion. I personally would much rather people tell me to my face how they feel than have them talking behind my back.”

The gentrifier

Prior to getting into the luxury condo market, Shaoul made a name for himself in the early 2000s by fixing up rundown tenement buildings downtown and rolling over rent-stabilized leases to make way for market-rate tenants. He founded Magnum in 1998, after he started renovating apartments for a building near Union Square that his parents purchased so they could house their business in the ground-floor retail.

The following year, he bought his first building, a tenement on Mott Street, by taking a mortgage on his parents’ property. Two years later, the Village Voice wrote about him in a story about strongarm tactics used by landlords to vacate rent-regulated apartments. Among other claims, tenants at a building Shaoul owned at Elizabeth Street said he had turned off their gas for more than a month.

From there, things only got worse. In 2006, when he started buying in the East Village, he became the face of gentrification in a neighborhood that was fighting tooth and nail to stop development. In what became an infamous moment, he was photographed confronting squatters in the building along with a crew of construction workers holding sledgehammers and crowbars. Hence the nickname, Sledgehammer Shaoul, a moniker that’s stuck with him to this day.

Shaoul recently bristled at the depiction. “Do I wish people didn’t say that? Of course I do,” he said. “I have four children and a wife, and kids come to my house for playdates and stuff. The last thing I want is for one of those other parents to Google me and something that’s not even true comes up. You don’t want to handicap your children with that.”

Sources said the criticism Shaoul and his partners received in those years likely played a part in him transitioning into other types of projects.

“I think it had a part in him getting out of the rent-regulation market,” said Brandon Kielbasa, director of organizing at the Cooper Square Committee, a tenant advocacy group. “If he hadn’t been contested, and if we hadn’t put up the battle we had, I think he would have continued in it for a while longer.”

More recently, it’s his own parents that have been the source of scandal. In 2014, Abraham and Minoo Shaoul accused their son of misappropriating millions of dollars through the refinancing of mortgages on properties he co-owned with them and treating Magnum like his “own personal piggy bank.” In one instance, they accused him of cheating them out of their interest in a building they co-owned at 166 Elizabeth Street in Noho.

Shaoul denied that Magnum was a family company, but the lawsuit nevertheless portrayed him as an ungrateful son. “The people he is stealing from are his own parents,” the complaint said.

Shaoul said both he and his mother now regret the suit, calling it “embarrassing.”

He added: “In any business, in any situation, shit happens. A lot of the lawsuit has to do with the attorneys getting in my mother’s ear, making things nasty and looking for every possible thing to get leverage. I regret and my mom regrets a lot of things that were said in that lawsuit.”

His mother did not respond to a request for comment.

Luckily for him, the bad press does not appear to have scared away investors.

“I discount a lot of those stories and we weren’t involved in any of them,” said Andrew Mathias, president of real estate giant SL Green, which has partnered with and lent to Shaoul in recent years. “My dealings with him have all been aboveboard and successful.”

Indeed, institutional real estate players, such as Lehman Brothers and Westbrook Partners, were attracted to him early on. In 2007, Westbrook and Normandy Real Estate Partners brought him in as an operating partner on a portfolio of 17 walk-up apartment buildings in Downtown Manhattan, which the partnership eventually sold to Jared Kushner for $130 million in 2013.

And the late Carmine Visone, a legendary managing director in Lehman Brothers’ real estate division, took Shaoul under his wing, bankrolling some of his early investments while simultaneously mentoring the young upstart with some tough love.

“He would make me come in on a Monday in August at 7 a.m. just because he knew I wanted to sleep at the beach on Sunday night with all my single guy and girl friends,” Shaoul recalled. “I’d have to get up at 5 a.m. to go meet him. He wanted me to know that he was watching. It was good for me.”

Industry darling

For the moment at least, Shaoul is under a different kind of spotlight.

“He’s got a lot going on but he can handle it,” said Michael Stern, the CEO of JDS Development, which had also tried to buy 100 Barclay. “We loved that building and Ben outbid us fair and square. We weren’t far off from where Ben was. I don’t think there was a material difference. I think he’ll do great.”

Fueling Shaoul’s growth has been some high-profile investors. SL Green provided a $97 million loan to help Magnum acquire and initiate construction on the Katz’s Deli project last year. Mathias told The Real Deal that Shaoul’s savvy in assembling the site at a relatively low cost basis was the reason for his interest in the deal.

Shaoul’s equity partners on 100 Barclay, 389 East 89th Street and 385 First Avenue include Forum Absolute Capital Partners, run by longtime real estate magnate Mikhail Kurnev. The company has also invested in projects such as 21 West 20th Street with Gale International.

Shaoul declined to comment on the specific equity breakdown at his projects. As for the amount of personal investment, he described it merely as “a lot.”

He said that since the recession he has been building a company that can operate at an “institutional level.” Industry insiders, however, say he operates almost entirely on gut.

“Ben definitely doesn’t care that much about what other developers are doing or what they think and it’s controversial sometimes,” Lansill said. “He’s an absolute nonconformist. He adapts his point of view based on instinct at any particular moment and he’s not afraid to change his mind.”

Brad Settleman of Tall Pines Capital, whose company is partners with Magnum at Bloom 62, a rental building in the East Village, said he has watched Shaoul mature over the last five years. “He’s become very thoughtful about his approach to the business and he takes his partners’ interests into consideration,” he said. “He has an incredible ability to manage several projects at once, which not everyone can do. It’s a rare talent and very little seems to fall through the cracks while he’s doing it.”

But the sheer quantity of deals on Magnum’s books is enough to get industry watchers whispering about Shaoul’s capacity to pull it all off — and whether or not his basis on all these projects allows room for error. Some said the simple volume of inventory at 100 Barclay is a lot to unload in this market.

Shaoul said he’s made a lot of personal guarantees related to loans on projects but claims he’s not worried. “I’ve been signing personal guarantees and recourse loans since I was 19,” he said. “ I’ve been responsible from day one. There’s no pressure for me.”