The battle for designing One Vanderbilt came down to three distinguished architecture firms, all with impressive international portfolios — and chops building complex office towers.

The developer, SL Green Realty, considered designs by Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates, Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, and Skidmore, Owings and Merrill for the $3.2 billion tower. Ultimately, the real estate investment trust went with KPF, whose glassy, tapering design is reminiscent of Chicago’s famed Willis Tower.

The runners-up have differing takes on what drove SL Green’s decision.

“[KPF] had a long relationship with Marc Holliday,” said T.J. Gottesdiener, managing partner at SOM, referring to the company’s CEO. “I thought we did a fabulous job, but it was a question of [where his] comfort level was.”

Jamie von Klemperer, president of KPF, noted that the firm worked with SL Green on only one project — the renovation of 1515 Broadway — before winning the One Vanderbilt gig.

“We never had the feeling that this gave us any advantage,” he said. “It appeared to us that all three firms were on an even footing.”

Regardless of whether one firm had a leg up (or not) in that giant project, for architecture firms, relationships with developers are crucial to scoring commissions.

This month, The Real Deal pored over permit applications filed with the city’s Department of Buildings and ranked the most prolific architecture shops in the city to determine which of them have maximized those relationships and designed the most square footage of new buildings in the five boroughs between Jan. 1, 2012, and Jan. 31, 2018.

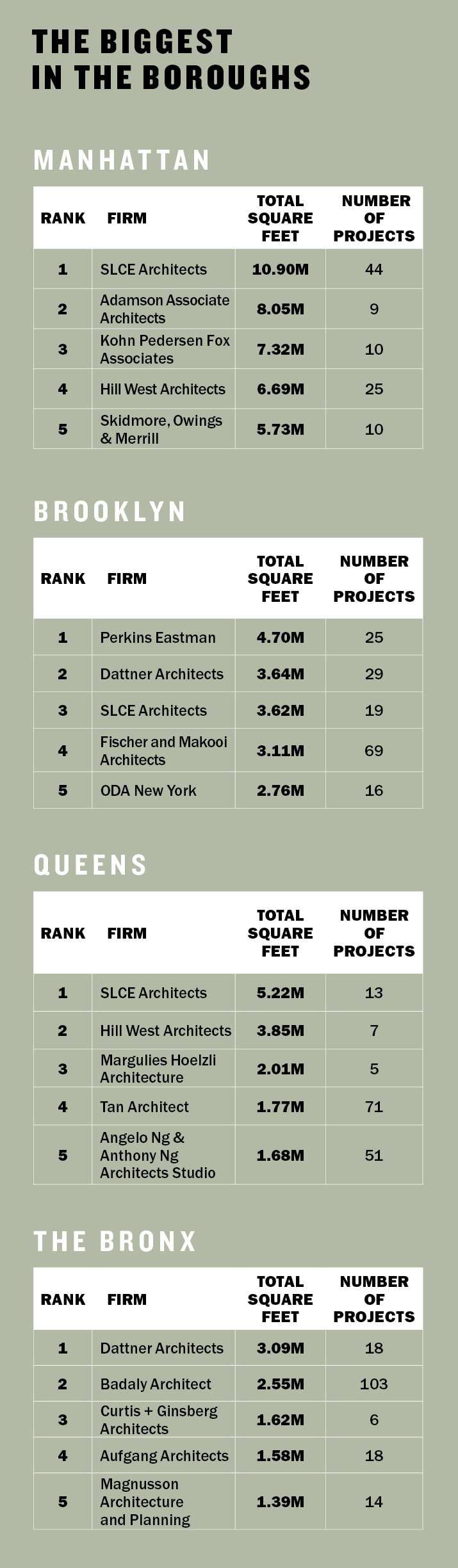

Taking the top spot was the Manhattan-based firm SLCE Architects with 20.69 million square feet across 87 New York City projects. It was followed by Hill West Architects with 13.09 million square feet across 43 projects and Dattner Architects with 9.54 million square feet across 65 projects. Rounding out the top five were Perkins Eastman and Adamson Associates Architects with 8.80 million square feet and 8.69 million square feet, respectively.

Collectively, the top 30 firms filed plans for 153 million square feet of new residential and commercial building construction during that six-year stretch. That’s the equivalent of roughly 54 Empire State Buildings.

Collectively, the top 30 firms filed plans for 153 million square feet of new residential and commercial building construction during that six-year stretch. That’s the equivalent of roughly 54 Empire State Buildings.

Just like developers, brokers, lenders and other real estate players, these architecture firms must adjust their practices to meet market conditions.

And at the moment, those market conditions include an oversupply of luxury condos, rentals and hotel rooms — along with a tight lending environment for ambitious projects. Some architecture firms have turned to affordable housing and infrastructure jobs to fill the void, but federal funding for both of those sectors may also now be in jeopardy.

To adjust to this new reality, some firms are doubling down on architectural specializations, while others are diversifying — in both the types of projects they’re taking on and the locations of those projects.

“I think we’re good at reading the tea leaves and figuring out that we should be spending the next two years focusing on, say, education projects because we think that’s where the money’s going to be spent more and more,” Gottesdiener said. “We’re all, to some degree, susceptible to market conditions.”

Divide and conquer

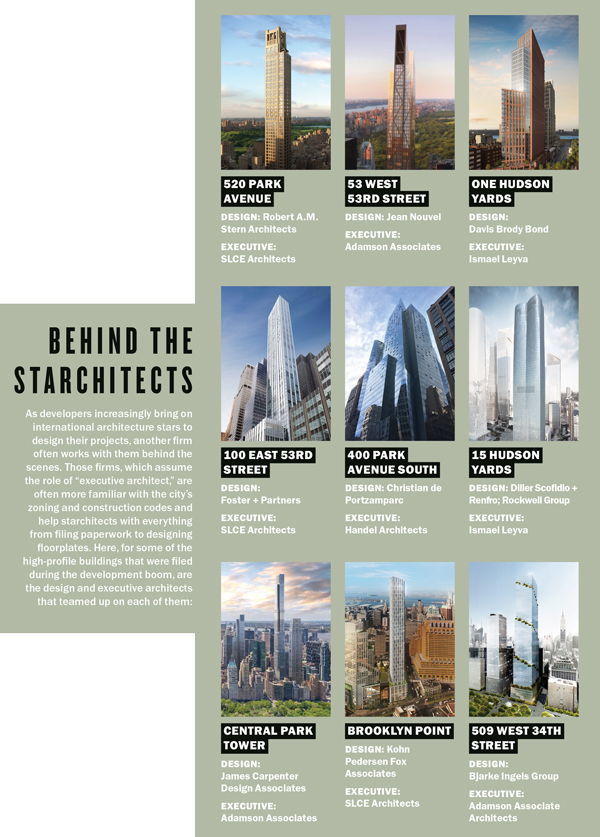

SLCE, though the most prolific, is also perhaps among the most discreet. The firm is linked to some of the most prominent residential developments in the city, but its name is often obscured in the shadow of a flashy international starchitect.

For instance, although Vornado Realty Trust’s 220 Central Park South was designed by Robert A.M. Stern, SLCE served as the executive architect. That role can range from handling construction paperwork to designing the floor plates for residential units.

Meanwhile, Adamson took on the same role at Extell Development’s Central Park Tower (where Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture and James Carpenter were the design architects) and at Tishman Speyer’s the Spiral (designed by Bjarke Ingels).

TRD’s ranking includes both the so-called executive architects — who often work behind the scenes — and the design architects (or starchitects), who often get public credit for projects.

SLCE partner James Davidson noted that while the majority of the firm’s work is as design architect, having separate design and executive architects on a project has become increasingly common.

Developers have, indeed, more frequently been tapping international design star power to buoy sales. But they often bring in a second architecture shop that’s more familiar with the city’s zoning and construction codes.

But those aren’t the only cases when two firms team up.

In some cases, they also join forces if they’re working in sectors they’re less experienced in. KPF, for example, which specializes in office design, often works with other firms (frequently Hill West) on residential projects, where apartment layouts are so crucial.

Although that kind of double teaming is common, sources say it can pose challenges.

“I have seen many situations where a design architect from abroad has tested the bounds of buildability and has wound up losing the commission,” said Davidson, though he declined to cite specific examples. “There are points at which a design architect’s concepts are so expensive that a seasoned developer would question the value added of such an undertaking.”

Stephen Hill, co-founding partner at Hill West, said his firm acts as a “reality check” on the visions of the starchitects it works with. He also wouldn’t name names.

“We’re good at enabling people to realize their vision,” said David West, the firm’s other co-founding partner. “But sometimes there are things that can’t be done.”

Sum of its parts

The division of labor doesn’t stop at the design and executive architect roles.

Dan Kaplan, of FXCollaborative, which was No. 18 on TRD’s ranking with 3.14 million square feet across 15 projects, said developers have increasingly sought more specialized firms for exteriors and interiors.

GID Development, for example, tapped different firms to do just that at its three-building mega project on the Upper West Side known as Waterline Square.

Richard Meier, Rafael Viñoly and KPF were selected as the designers of each of the buildings, and Champalimaud Design, Yabu Pushelberg and Groves & Co., were tasked with the interiors.

SOM’s Gottesdiener said that his firm never takes on executive architecture work, though it will occasionally pair up with other firms at the request of the property owner. Such was the case at the Baccarat Hotel and Residences, where French duo Gilles & Boissier designed the hotel’s interiors.

SOM’s Gottesdiener said that his firm never takes on executive architecture work, though it will occasionally pair up with other firms at the request of the property owner. Such was the case at the Baccarat Hotel and Residences, where French duo Gilles & Boissier designed the hotel’s interiors.

“We will not take a project on just to do someone else’s work,” Gottesdiener said. “They are often the kinds of firms that don’t have the depth to take a project from design all the way to completion.”

Kaplan said the trend sometimes creates a situation in which the architects aren’t as deeply involved or invested in the entire scope of the project.

“What I suppose is gained is that is you get expertise in those particular silos,” he said. “I do feel that it’s an unfortunate development. I think something gets lost in the end product.”

John Woefling, principal at Dattner, also argued that it’s risky to “break up work into overly specialized pieces.”

“When you do it that way, you just have a bunch of surface treatments that aren’t connected to the overall design,” he said.

Some said that splitting up the work can also increase a project’s time frame and cost because there’s an extra degree of coordination required between teams. But others said that in the long run, having more expertise at each level results in savings.

Gene Kaufman — known for his extensive work on budget hotels — said that dividing up a project can result in a more efficient design process. Kaufman, who ranked No. 13 citywide with 4.16 million square feet at 54 projects, said he’s currently working on a hotel in Australia with a local firm because he’s able to design such projects quickly.

And Ismael Leyva, who designed the interiors for Zaha Hadid’s 520 West 28th Street High Line project, said developers are often driven to hire more than one architect so that they can market more than one high-profile name.

But Leyva said that when it does happen, the teams at each firm are in constant communication and effectively end up functioning as one studio.

“It’s not like they work on the exterior, and we work independently on the interior,” he said.

Architect in the coal mine

Long before brokers arrive on the scene, architecture firms feel the ups and downs of the market.

In October, SLCE won a contract to work on TF Cornerstone’s 56-story, 800-unit residential tower at 52-03 Center Boulevard in Long Island City — the shop’s largest new gig of the year by square footage. Then, late last month, the developer filed plans for a second, 46-story, 394-unit building at the site. (ODA New York is the project’s design architect). And SOM, for instance, is designing Brookfield Property’s Two Manhattan West, one of the largest new buildings for which plans were filed last year.

The projects — like all the others that the firms secured in 2017 and early in 2018 — offer a window into what’s coming down the development pike.

In addition, while Manhattan may deliver the highest profile assignments, there’s plenty of work to vie for in the other boroughs.

For example, while most of SLCE’s work — 10.90 million square feet — was in Manhattan, the firm was also the most active in Queens during the six-year period with 5.22 million square feet in that borough.

And the firm also ranked No. 3 in Brooklyn with 3.62 million square feet, following Dattner and Perkins Eastman, which had 3.64 million square feet and 4.70 million square feet, respectively.

Dattner, meanwhile, was also the most active firm in the Bronx with 3.09 million square feet.

Architects have seen increased activity in the outer boroughs over the past few years, said David West, whose firm racked up 3.85 million square feet of work in Queens, which landed it at the No. 2 spot for that borough. Its commissions in the borough included Tishman Speyer’s three-building residential project at 28-10 Jackson Avenue in Long Island City.

And snagging assignments for condo developments in the outer boroughs is becoming increasingly competitive, especially because those projects often don’t have the same size constraints as those in Manhattan, said Nancy Ruddy, co-founder and principal of CetraRuddy Architecture, whose firm ranked No. 15 citywide with 3.64 million square feet across 14 projects, including Delshah Capital and OTL Enterprise’s 22 Chapel Street in Brooklyn and Nathan Berman’s 20 Broad Street in Manhattan.

“Part of the challenge is, how do you get that sense of luxury and sophistication in a smaller footprint?” asked Ruddy, referring to Manhattan.

“Your personal space has gotten smaller, but the amenity spaces in the building are continuing to get larger,” she added.

Pipeline prep

At the same time, architects are preparing for the next wave of work.

Residential construction spending — which reached $16 billion in 2016 — is expected to drop to $11.6 billion in 2018 and then to $10.6 billion in 2019, according to estimates from the New York Building Congress.

But both affordable housing and the city’s aging infrastructure are considered promising near-term opportunities.

Magnus Magnusson, founder of Magnusson Architecture and Planning, which took the No. 21 spot with 3.01 million square feet across 30 projects, noted that attitudes toward affordable housing design have evolved over the past 30 years.

His firm has been working on the Melrose Commons Urban Renewal Plan, the massive affordable housing development in the South Bronx, since the late 1980s. The project, which is now in its final phase, not only played a role in elevating how affordable projects are perceived by the design community, he said, but it also helped the firm score other similar jobs.

“We kind of fell into it, and I think after we did our first affordable housing project in 1989, it got us a lot of attention,” he said. “People weren’t thinking of affordable housing as projects worthy of design awards.”

But the new federal tax law reduces the value of a crucial affordable housing funding source: low-income housing tax credits. A study released by national accounting firm Novogradac & Company found that the affordable housing supply will drop nationwide by 235,000 units over the next 10 years as a result of the law.

Meanwhile, President Trump’s recently announced infrastructure plan decreases the amount of federal funding provided for improving roads and mass transit, calling on local governments to pony up. Some of the architects who spoke to TRD said they are concerned that this could stunt projects in the city, though it’s not yet clear how the plan will play out.

“Government work is probably not going to be as pronounced as it was previously,” Gottesdiener said, noting that in the interim, healthcare, education and commercial work remain strong prospects.

But he also pointed out that the president’s infrastructure plan relies heavily on the private sector to finance projects, so there may be different kinds of opportunities — like design-build jobs, where the two processes happen simultaneously.

Kaufman noted that having diverse practice areas didn’t shield firms from the last downturn.

“People who diversify and effectively dilute their focus may end up losing that competitive edge,” he said.

Still, in addition to designing hotels, Kaufman’s firm does a lot of middle-market residential and student housing work, the latter of which tends to be less market sensitive. He said hotel commissions have slowed as lenders shy away from such projects, due in part to zoning hurdles and the growing competition from Airbnb and other home rental platforms.

And for some firms, diversifying means expanding geographically.

KPF’s von Klemperer said the firm’s offices in New York, London, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Seoul and Abu Dhabi help it stay busy even when certain markets get soft.

He also said the firm’s presence at One Vanderbilt and at Hudson Yards, where it worked on 10 and 30 Hudson Yards, has set the stage for future work — whether in the form of new buildings or major renovations. And as the architects of One Vanderbilt, the first building to benefit from the Midtown East rezoning, the firm’s in a good position to score more work nearby.

“The building is almost like the first step in a more sustained process,” von Klemperer said.

“We’re seeing a number of nibbles, and studies to see what other sites can be renovated.”

Jonathan Marvel, principal and founder of Marvel Architects, which clocked in at No. 25, said that his firm has always looked outside New York to keep its pipeline of projects full. The firm, which has an office in San Juan, Puerto Rico, is currently doing a lot of post-Hurricane Maria recovery work.

“I wouldn’t say it’s profitable, but at least we’re staying busy,” he said. “You have to keep your eye on the prize. It’s all about design, and it’s about reinventing the wheel.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly spelled Ismael Leyva’s name and incorrectly identified the executive architect on Related Companies’ 520 West 28th Street. Leyva served as both interior and executive work on the project, though the architect said in an interview that he only did the interiors.