It’s one thing to land a listing, but it’s quite another to sell it. And that, in a nutshell, is the conundrum in Manhattan’s residential market these days.

Agents have now been navigating the softening sales landscape for nearly two years. The inventory crunch that defined the post-recession stretch has not only let up, but it’s also swung in the opposite direction.

For-sale properties have piled up, new developments are flooding the market and buyers are taking their pretty old time.

Brokers claim that the current atmosphere has made them more selective when it comes to which listings they’ll take on.

“Anytime there’s too strong a difference between the way the buyer and seller perceives and values the market, the agent is in a much more complex situation,” said Warburg Realty President Clelia Peters. “The agent is the interpreter of those sides.”

Related: Sealing deals and taking names

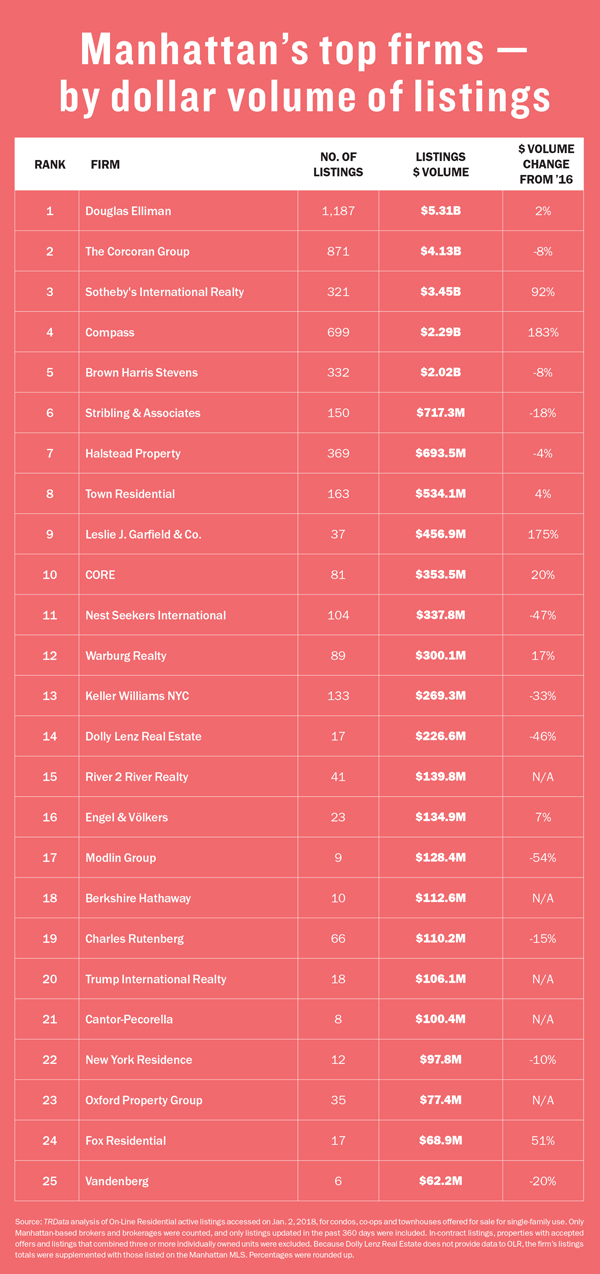

Amid this confused market, this month The Real Deal took a one-day snapshot of thousands of active listings on On-Line Residential in early January to determine which NYC brokerages had the greatest dollar volume of for-sale properties on the market. We then shared that information with the firms, most of which sent us deals to help fill in our findings. The goal was to get a window in the battleground for listings, the gateway drug to the Holy Grail: a closed sale.

Despite finishing second on the more-coveted closed sales ranking, Douglas Elliman clocked in at No. 1 on this line-up with 1,187 listings valued at $5.31 billion, up 2 percent from $5.2 billion in May 2016, the last time TRD published its ranking. Those listings included new developments like 432 Park and Ian Schrager’s 160 Leroy, as well as such pricey resales as an $80 million Upper East Side townhouse at 8 East 62nd Street.

The Corcoran Group, meanwhile, took the No. 2 spot, amassing 871 listings totaling $4.13 billion.

Those two heavy hitters were followed by Sotheby’s International Realty (with 321 listings valued at $3.45 billion), Compass (with 699 listings valued at $2.29 billion) and Brown Harris Stevens (with 332 listings valued at $2.02 billion).

Together, the top 12 brokerages had 4,403 listings valued at a total of $20.6 billion — a 27 percent increase from 2016’s $16.2 billion and up 65 percent since 2015’s $12.5 billion.

Clelia Peters and Gary Malin

The average listing price for those firms was $5.2 million, up 18 percent from $4.4 million in 2016 and up 30 percent from $4 million the prior year.

But the residential market was marked by a lack of adrenaline in 2017, with too much inventory, price-sensitive buyers and lingering properties.

The Manhattan brokerage business also saw its share of drama. A high-stakes battle over who controls all of these listings and how they’re disseminated to consumers raged for much of the year, pitting listings website StreetEasy against some of city’s biggest firms.

At the moment, some firms, including Elliman and the Corcoran Group, have made peace with StreetEasy, while others have defiantly opted to withhold their properties from the website and feed them into competing systems, including the Real Estate Board of New York’s recently launched listings platform, dubbed the RLS.

“To me, that’s the most essential part of what all of us do,” said Gary Malin of Citi Habitats, referring to how the firm connects with clients. “We’re in the hospitality business. Creating systems that enable agents to be more impactful in communicating with clients is huge.”

When to land a listing

In today’s icy market, most brokerage heads agree that getting a deal done comes down to how realistic the seller is about price.

“If you don’t have the right price, that property is going to sit and sit and sit and sit,” said Elliman’s New York CEO, Steven James.

For example, the penthouse at the Richard Meier-designed 165 Charles Street finally closed in 2017 after bouncing on and off the market for more than three years as pricing jumped all over the map. The owner, British magazine publisher Louise Blouin, changed brokers three times and at one point upped the ask to $40 million.

In December 2016, Halstead Property’s Anne Prosser came in after the previous exclusive expired and listed the apartment for $29.9 million. It closed a year later, for $23.7 million. “It’s a spectacular unit,” said Prosser. “But $40 million was unrealistic.”

Part of the problem, Prosser said, was that it was competing with a crop of new luxury condo buildings in the West Village and Tribeca, including the Witkoff Group’s 150 Charles Street, Related Companies’ 70 Vestry and Ian Schrager’s 160 Leroy.

And therein lies the problem for sellers. Buyers are swimming in choice.

In Manhattan, there were 5,451 active listings at the end of 2017, up slightly from 5,393 the year before, according to an Elliman report. That’s an increase of 30 percent from the low point in 2013, when there were 4,164 active listings.

The growth was largely due to an influx of luxury listings. Available inventory of high-end condos and co-ops increased 13 percent year-over -year, to 1,439.

At the same time, the absorption rate — defined as the time it would take for all existing inventory to sell out — increased to 17 months for luxury listings, up 30 percent from 13 months the previous year.

Elliman’s James said that with so many options, buyers are worried about making the wrong decision.

“The buyer today is nervous, they’re nervous about making a mistake, and certainly they’re nervous about making a fool of themselves,” he said.

Peters said that, “buyers are feeling empowered.” She noted that they will put off making decisions for weeks rather than pouncing on an apartment immediately, as they would in a stronger market. “There is a feeling of no urgency in the market,” she said.

Buyers are also savvy and informed, particularly due to how much information is accessible online, said Tamir Shemesh, a broker with Douglas Elliman.

For brokers, this translates into having to expend more effort to sell a listing. “It takes longer to bring buyers and the sellers to an acceptable level, and time is money,” he said.

While negotiations with sellers are an issue in the resale space, developers are also very much attuned to price sensitivity in the market, Shemesh said. Buyers are willing to pay a premium for the “new car” smell, but only if it stands out from the competition, he added.

“It’s tough out there,” said Halstead Chair and CEO Diane Ramirez. The delicate pricing game means brokers are constantly confronted with the question “How do I win the exclusive but not get myself caught with an apartment that’s going to linger on the market?” she said.

That dilemma is making some brokers more selective about which listings they take. Anisa Saroop, a broker with Brown Harris Stevens, said she rejected a listing for a three-bedroom on the Upper East Side because the seller was adamant about a price Saroop felt was unrealistic. “I don’t want to sell someone a dream,” she said.

“A few years ago, there was always that dream that there’s that one buyer who will pay the price,” said Ramirez. That, she said, is no longer the case. “It doesn’t matter what the price is, an aspirationally priced apartment is not going to sell.”

Indeed, many units are going through multiple price cuts before selling at far lower prices. A Tribeca apartment belonging to J. Crew head Mickey Drexler dropped its price five times since 2015, going from $35 to $18.5 million. A West Village apartment that once belonged to Robert De Niro has been on and off the market for rent and sale since 2012. Most recently, its ask was slashed to $23 million, down from a high of $39.8 million in 2015. And a Park Slope townhouse that sat on the market for two years asking $15 million dropped to $9 million. A contract was signed for it a month later.

A languishing listing is a drag on a broker’s time — and her reputation.

“If you are known as a broker who always overprices things, that doesn’t bode well for you and doesn’t bode well for your seller,” said Stribling & Associates President Elizabeth Ann Stribling-Kivlan. She explained that if a broker has that reputation, some potential buyers might make lowball offers.

“It’s much better to be accurate and be the second agent,” Peters said, using a common broker mantra. “There’s only so far you should go in adjusting to the seller’s expectations.”

Listing tug-of-war

In the past year, agents and firms have had to make more difficult decisions about how to publicize the listings they have — and how much money to spend on advertising.

That’s because in 2017, StreetEasy’s parent company, Zillow, rolled out several controversial pay-to-play features allowing brokers to advertise next to someone else’s listing. Premier Agent was already a major moneymaker across Zillow’s other sites, bringing in $604 million in 2016, which comprised 71 percent of the company’s total revenue. Then it began charging agents $3 a day for rental listings.

In August, 10 firms — including BHS, Town Residential, Compass and Stribling — agreed to boycott StreetEasy and feed their listings through REBNY’s RLS. About 200 other firms, including CoStar’s apartments.com and Robert Murdoch’s Realtor.com, have opted into the RLS.

Although the move was significant, it was hardly a death-blow. The two biggest brokerages, Elliman and Corcoran, allied with StreetEasy by year’s end, and many brokers are manually providing listing data to the site, even while the brokerages they work for aren’t.

Nevertheless, the tug-of-war has put the spotlight on who controls Manhattan’s residential listings.

“StreetEasy is not as comprehensive as it was six months ago,” said Stefani Berkin of Charles Rutenberg, whose firm clocked in at No. 19 with $110.2 million in listings. Her firm is feeding its listings into the RLS, but brokers still have the option of using StreetEasy.

StreetEasy remains dominant, but rivals — both upstarts and entrenched firms — sensing an opening, are now angling to get a piece of the digital listings space.

The ensuing fragmentation, Berkin said, has put an extra burden on brokers. “To be completely honest, it puts a higher demand on us agents to know what’s on StreetEasy and what isn’t.”

“From all of this has spun out this incredible amount of competition, and now there’s all these new players,” said Bess Freedman, co-president of BHS.

Realtor.com agreed to syndicate its listings through the RLS and has been making a concerted effort to grow its New York presence; the New York Times joined the fray in September and began publishing listings, and TRD is also joining the mix. Meanwhile, Perchwell, a startup portal that competes with industry stalwarts OLR and RealPlus, has gained traction. CORE, Warburg, Berkshire Hathaway and Stribling all signed on to use it in 2017.

“Ideally we have one feed, one powerful feed,” said Freedman, who’s been an outspoken proponent of REBNY’s RLS as a central spigot. “That keeps the data quality the best, and then everyone has the same access to information.”

Up until now, StreetEasy has refused to accept REBNY’s feed, claiming that it would compromise the accuracy of the listings it previously received directly from brokers. However, in January, Zillow CEO Spencer Rascoff and REBNY President John Banks came to the table to negotiate.

Citi Habitat’s Malin said his firm spent a lot of time in 2017 focusing on SEO to amplify its presence in online searches.

“It’s part of what you need to do,” he said. “Things change quickly in this industry. Everyone talks about how great technology is. I think it’s key. But great technology without great people and vice versa isn’t a winning formula.”

“It’s hard to tell how this is all going to play out,” said Freedman, “and if there will be an ultimate winner.”