UPDATED, July 6, 4:44 p.m.: In 2002, Steve Croman, a slick broker-turned-landlord who had amassed an enviable portfolio of Manhattan rental buildings, set his sights on a pair of Upper East Side walk-ups on 72nd Street near Central Park. It was there that he and his wife, Harriet, began building their dream home, evicting tenants from 23 apartments to create a 19,000-square-foot mansion with eight bathrooms and a rooftop pool. But Croman is not likely to be spending much time at that palatial residence in the coming year.

In June, the landlord walked into a Lower Manhattan courthouse and pleaded guilty to fraud and larceny, agreeing to serve a year in jail in decidedly less extravagant accommodations on Rikers Island, where his cell is not likely to measure more than 70 square feet. “Are you pleading guilty voluntarily?” New York State Supreme Court Justice Jill Konviser asked Croman, who replied in a low, froggy voice, “Yes, I am.”

“Are you pleading guilty because you are in fact guilty?” she asked. “Yes,” he answered.

Then the judge warned Croman not to get arrested before his September sentencing: “Not for jaywalking, not for riding your bike on the sidewalk.”

But long before Croman found himself in that courtroom — before New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman dubbed him the “Bernie Madoff of landlords” — he garnered a reputation as one of the city’s most notorious property owners, building the largest multifamily portfolio in the fast-gentrifying East Village and clearing out rent-stabilized apartments as property values skyrocketed. Now, with his guilty plea, he’s become a poster boy for the current moment in the decades-long conflict between tenants and landlords, which has reached a fever pitch in New York.

“The stakes have never been as high as they seem to be in the last five years or so,” said Mary Ann Hallenborg, a professor at the NYU Schack Institute of Real Estate, who’s written books on both tenants’ and landlords’ rights.

Related: How culpable are banks when landlords push out rent-stablizied tenants?

In the past few years, authorities have pursued case after case against landlords, but tenants and advocates have argued that not enough is being done to hold those landlords fully accountable for their actions. That might soon change: City and state lawmakers are currently pushing for tougher laws to regulate harassment that could have major implications on the city’s roughly 1 million rent-stabilized apartments.

While most agree that Croman’s actions towards tenants were at the very least dubious and at the worst criminal, there is less consensus about the broader clampdown being pursued against multifamily owners.

In interviews with The Real Deal, landlords, investors, lawyers and industry lobbyists all said there is a growing feeling that the deck is being stacked against property owners and even that New York may be on a slippery slope toward landlord harassment. They contend that prosecutors are politically grandstanding and legally overreaching. New legislative proposals, including one that would greatly expand the legal definition of criminal tenant harassment, could criminalize honest owners and even dissuade them from upgrading the very properties that their tenants live in, those sources argue. Tenant advocates and Democratic politicians, however, insist that current laws make tenant harassment a relatively low-risk vehicle for landlords to line their pockets.

For landlords and investors there is, indeed, a lot of money on the line. The city’s multifamily market logged $14.1 billion in sales last year. In recent years, institutional investors and lenders like Blackstone and Wells Fargo have backed some of the largest deals. But in some cases, multifamily bets are only worth it for investors if rent rolls are increased in a short window of time.

And as billions of dollars are being poured into that market, the number of harassment investigations is on the rise.

The state’s Homes and Community Renewal agency, which oversees the rent-stabilization program, logged a nearly 23 percent increase in the number of harassment cases it probed between fiscal years 2013 and 2016.

“Tenant harassment is like termites; where there’s one, there are many,” said Aaron Carr, founder of the Housing Rights Initiative, a nonprofit that’s organized rent-fraud suits against some of Manhattan’s largest landlords. “To solve a termite problem, you have to eliminate the termite nest. And the nest is almost always found in the business models of predatory landlords.”

While lawmakers have pledged to go after the bad apples who push the limits of the housing laws, concern is mounting that the new laws will put a damper on the multifamily sector and lead to a broader fishing expedition.

“If they start broadening the language like this, everybody could potentially get caught up in it, no matter how in compliance with the law you’re going to be,” said Bronstein Properties principal Barry Rudofsky, who owns dozens of rental buildings with 4,000-plus units in Queens.

“The people who enforce these laws don’t distinguish between [landlords] who do the right thing and the really bad guys out there,” he added.

Strong-arming tenants

While Schneiderman’s Croman prosecution is the most high-profile case of its kind in recent New York memory, in the end the landlord’s downfall had nothing to do with the ex-cop he allegedly hired to scare tenants out of buildings, or the toxic levels of lead dust and nonstop construction that, according to state prosecutors, made living in his buildings dangerous. His downfall also had nothing to do with violating the state’s criminal anti-harassment law, which can carry a sentence of four years in prison.

Instead, Croman pleaded guilty to lying to his banker about the rents he was collecting at six Lower East Side, Chelsea and Nolita buildings so that he could nab a bigger loan — a violation that could have put him behind bars for 25 years.

Now, as they push for stricter penalties in Albany and at City Hall, tenant rights advocates and lawmakers who back their movement are pointing to the fact that it was easier to take Croman down for his bank dealings than for allegedly strong-arming tenants.

“It is extraordinarily hard to prove tenant harassment, because the law defines it as a course of conduct over time,” said tenant activist Michael McKee, who heads Tenants PAC, a political action committee that backs tenant-friendly candidates for public office. “So you have to show there are repeated and repeated and repeated instances of harassment.”

The difficulty of proving that a landlord’s actions served the explicit purpose of repeatedly harassing tenants is what makes winning even civil tenant-harassment lawsuits so rare, advocates argue.

“Intent is the thing we struggle the most with,” said Stephanie Rudolph, an attorney at the Urban Justice Center, a legal-services nonprofit. “And I think in all but the most egregious situations with ‘lucky facts’ — where tenants have gotten things on audio or video — it’s hard.”

At an April City Council hearing, a city representative seemed to back that up.

The representative noted that between 2014 to 2016, New York City Housing Court only ruled that harassment occurred in 2 percent (or less) of cases brought by tenants. In 2016, for example, only 15 of the 977 cases that tenants lodged were decided in their favor — a fact advocates say illustrates the need for stricter laws.

But Mitchell Posilkin, general counsel for the landlord group the Rent Stabilization Association, said the figures are proof that harassment is less prevalent than tenants claim.

“In terms of actual instances in which Housing Court actually found that there was harassment, you could count on the fingers of one hand,” he said. “The reality here is that there’s a lot less than what the tenant advocates claim. I think it’s really incumbent upon those who want to see further legislation to prove their point, not just to make a lot of noise.”

In May, Schneiderman introduced state legislation to strengthen rules on tenant harassment. And over the last few years, he and others — including Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance — have increasingly targeted landlords, both criminally and civilly. So far, the results have been mixed.

In late 2014, the AG initiated a civil case against Lower East Side landlord Sassan “Sami” Mahfar alleging illegal buyout practices and construction harassment. When the two sides settled for $225,000 this past May, Schneiderman said his proposed laws would have allowed him to prosecute this case (and other similar cases) criminally.

In June 2015, the AG also brought criminal charges against Daniel Melamed, accusing the Brooklyn landlord of filing bogus forms with the city, stating that one of his Crown Heights buildings was empty during construction when, in fact, tenants were living there. Late last month, just two weeks after Croman pleaded guilty, Melamed was convicted during a bench trial of illegally evicting tenants. But he was acquitted on the top charge of filing false paperwork, as well as a misdemeanor of endangering a child.

In an interview with TRD late last month, Melamed, who faces up to a year behind bars when he’s sentenced in September, painted the prosecution as a political witch hunt.

“He’s going after every single landlord out there whether there’s a case or not,” the landlord said during a phone interview. “Schneiderman has an agenda to get re-elected, and he’s pushing that agenda.”

In August 2015, the AG’s office launched an investigation into the controversial broker-turned-landlord Raphael Toledano, who was busted when tenants at 444 East 13th Street recorded employees at the building’s management company intimidating tenants. Toledano, who fired the management company, later settled the harassment claims for $1 million.

And then there’s Joel and Amrom Israel — the Brooklyn brothers who admitted to hiring drug addicts and vandals to use baseball bats and pit bulls to intimidate rent-stabilized tenants at their buildings in Bushwick, Williamsburg and Greenpoint.

Rolando Guzman helped organize tenants at 300 Nassau Avenue, where one tenant was paying $754 a month in an area where $3,000 is now the market rate. Guzman said that starting in 2013 construction began wreaking havoc in the building: A toilet pipe leaked raw sewage into apartments, and the building’s boiler was mysteriously destroyed with an ax, cutting off heat.

The brothers faced up to four years but struck a deal in late 2016 with the Brooklyn district attorney that got them out of jail time in exchange for paying tenants a total of $350,000.

The agreement was seen by many as a slap on the wrist.

“[The Brooklyn DA’s office] called me and asked me to give them a quote in their press release,” said Judith Goldiner, attorney-in-charge at the Legal Aid Society’s Law Reform Unit. “I said ‘Sure, I’ll give you a quote, if the quote is I’m extremely disappointed with this result.’”

Goldiner said the Israel case is a prime example of why reform is needed.

“We think if anyone should’ve been put in jail, it should’ve been the Israel brothers, given what they did,” she added.

Others who have been in the crosshairs include landlords Dean Galasso, who’s currently facing mortgage-fraud charges, and Ephraim Vashovsky, who allegedly cut tenants’ heat in single-digit winter temperatures, causing a toilet bowl to freeze. Vance charged Vashovsky last year with reckless endangerment, among other offenses. That case is still pending.

Schneiderman’s legislation, meanwhile, would broaden the definition of “criminal” harassment to include practices like filing frivolous lawsuits and construction harassment, which are currently civil offenses on the city level. Sources say construction harassment has been the slumlord tactic du jour during this economic cycle (while illegal buyouts were the bread and butter of the last cycle) and that the law is lagging today’s reality.

State Sen. Daniel Squadron, one of many Democratic lawmakers backing the push for stronger tenant protections

Matt Engel, president of the Community Housing Improvement Program, or CHIP, an industry group, said that while “harassment against tenants sounds like something everyone should be concerned about,” the language in some of the new proposals is vague and doesn’t clearly differ from what’s already on the books, other than that it would give prosecutors more leeway to decide what constitutes harassment.

“We need to identify specific behaviors that we believe are being violated … and that don’t already have laws and a means [with which] to go after,” said Engel, whose Langsam Property Services owns or manages 8,000 units in the New York metropolitan area.

How to horse-trade

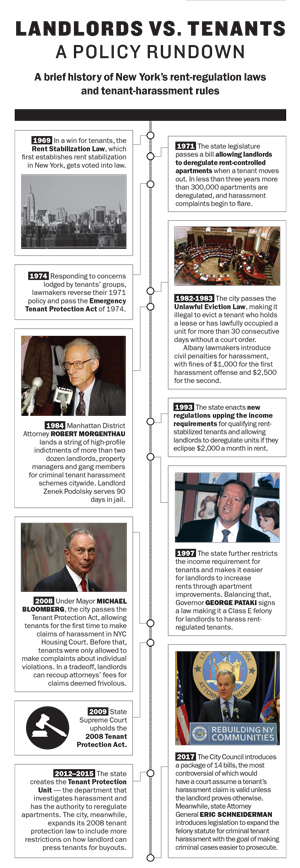

The rules governing tenant harassment in New York are a hodgepodge of criminal and civil statutes that have been pieced together through political horse-trading over the past few decades.

One of the seminal moments in that political tug-of-war came in 1997. That’s when Albany lawmakers amended the 1969 Rent Stabilization Law — the statute that established rent stabilization in New York — to make it easier for landlords to flip units to market rate, the holy grail for rent-regulated property owners. To do that, the state lowered the cap on the income a family in a rent-stabilized unit could earn annually to $175,000 from $250,000 and increased the amount landlords could hike the rent during vacant periods.

A ProPublica analysis of state rent-regulation figures between 1994 — when the first deregulation laws went into effect — and 2015 found that more than 153,000 apartments were removed from rent regulation through those two measures alone. (Another 48,000 were lost to co-op and condo conversions.)

Balancing that 1997 giveback to landlords, lawmakers also raised the civil penalty for harassment to $5,000 from $1,000. They also made it a Class E felony (a criminal act punishable by up to four years in prison) for a landlord to “cause physical injury” to a rent-regulated tenant with the intent of pushing them out.

Sherwin Belkin, a Manhattan real estate attorney and an expert on rent regulation, said the new laws could have a “chilling effect on responsible owners when it comes to owning and maintaining their property without fear that — if a door cracks or a window breaks — they suddenly may be prosecuted.”

“I’m not Pollyanna, and I’m not going to pretend there are not landlords out there that act in nefarious ways and are motivated by dollars or greed,” he said, “but what concerns me is that to catch the few bad apples in the barrel, [the AG and City Council] are going to sweep in a lot of good apples with the bad.”

The proposals, industry sources say, could have a crushing effect on landlords’ finances in the form of steep legal fees and administrative costs, and could deter investment for fear that it may be perceived as construction-related harassment.

And, sources say, the ripple effect could extend to lenders, investment sales brokers and others.

Michael Tortorici, executive vice president at the commercial brokerage Ariel Property Advisors, said the laws passed by the City Council in 2008 and 2015 that increased protections for tenants led to extended precontract due diligence and slowed down some deals.

“In some cases, they have scared certain buyers off of moving ahead with certain deals,” he said. “They’ve slowed down transactions a bit, more than they’ve impacted pricing.”

The new proposals, he said, could make buyers “more conservative in projecting turnover of stabilized units” and force owners to prepare for higher legal fees. But, he added, it’s too soon to gauge any possible impact on transaction volumes or pricing.

One multifamily landlord with a large portfolio of rent-stabilized units said if this new battery of legislation passes, it could deter property owners from investing in building improvements and scare off future investors.

“All of these tenant-harassment laws have second- and third-orders of unintended consequences,” said the landlord, who asked to remain unnamed. “I think that has an incredibly apparent chilling effect on reinvesting in and renovating these buildings. Why would you do it if you’re going to be in court with tenants all the time because they feel you’re trying to push them out when you’re cleaning up the common areas or you’re renovating the apartment next door?”

CHIP’s Engel echoed that point: “Our concern is that when legislation is passed, that makes it that much more onerous and challenging for the good actors to manage buildings,” he said. “People will just decide that [being a landlord] in this city is too difficult and they’ll go find somewhere else.”

But the left-leaning City Council — backed by New York City Public Advocate Letitia James and others — has gone to bat for tenants.

In April, the body proposed a package of 14 bills, the most controversial of which would create a “rebuttable presumption,” meaning New York City Housing Court would assume a tenant’s claim to be true unless the landlord could prove otherwise.

The idea is to ensure that landlords have a clear paper trail for things like construction plans and buyouts that prove they were following the letter of the law. The legislation would also prevent landlords from contacting tenants during “unusual” hours, require owners who’ve been found guilty of harassment to keep an escrow account of 10 percent of the rent roll to pay relocation fees, allow the City Council to award attorneys’ fees to tenants and create a tenant advocate position in the mayor’s office, among other things.

City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito, who proposed the “rebuttable presumption” regulation, declined to be interviewed, but in a statement to TRD she said the bill “will empower and strengthen tenant protection.”

She also said it will “put the onus on landlords to prove their actions are legally defensible.”

The council’s proposed laws coincide with a decidedly more pro-tenant environment on the other side of City Hall under Mayor Bill de Blasio.

Since 2014, the city has earmarked $155 million to provide free legal assistance to low-income tenants facing eviction, and the number of tenants represented by an attorney has shot up to 27 percent from 1 percent.

Landlords and real estate attorneys say that in addition to gumming up the already overburdened courts, the legal assistance creates a ripe environment for tenants to game the system by dragging eviction cases out, regardless of the merits.

Rosenberg & Estis’s Luise Barrack, the head of the firm’s litigation division, said she’s seen nonpaying tenants prolong eviction cases for more than a year by filing every motion and petition allowed by the court.

“Some tenants realize they can scam the system. It could be months into the process, and for some small owners, it’s a real hardship,” she said.

Daun Paris and Peter Hauspurg, the husband and wife who own and run the commercial brokerage Eastern Consolidated, said it took them nearly two years to evict a trio of nonpaying tenants in one apartment at a rent-stabilized property they own uptown.

“There are no rules that apply to anybody but the landlords, and they’re used against them,” said Paris.

Taking off the gloves

The New York real estate industry, which spent more than $35 million in 2016 lobbying Albany and municipalities, does not have a track record of sitting out fights.

The industry’s three main lobbying groups in the city — the Rent Stabilization Association, the Real Estate Board of New York and CHIP — have all come out against various aspects of the proposed legislative measures.

REBNY, which is led by John Banks, has publicly said that the “rebuttable presumption” requirement would “turn the most basic concept of justice — ‘innocent until proven guilty’ — on its head,” while the RSA has said that with 14 state and local laws already in effect, “the issue has been dealt with successfully and repeatedly.”

Both CHIP and the RSA have also challenged the notion that harassment is, in fact, even on the rise. “The data just do not support the City Council’s desire to increase legislation,” said CHIP’s Engel.

The RSA has pointed to HPD data it obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request on so-called certificates of no harassment, which multifamily landlords are required to have tenants sign off on before demolishing rental properties. The group claims that out of 361 filed certificate applications between fiscal years 2014 and 2016, only five were denied.

The RSA has also pursued legal challenges: The organization challenged the city’s 2008 Tenant Protection Act, arguing that it overstepped by legislating rules covering rent stabilization, which currently fall in the state’s domain. But the following year the state Supreme Court upheld the law.

And until recently, the RSA was locked in a three-year legal battle with the Homes and Community Renewal agency over nearly a dozen state rent-stabilization amendments passed in 2014 on Governor Andrew Cuomo’s watch. Among other things, it created the Tenant Protection Unit — the department that’s returned some 60,000 improperly deregulated units back to the system and churned out investigations that served as the basis for many of the recent high-profile harassment cases, including Croman’s and the Israel brothers’.

The RSA lawsuit was dismissed in state Supreme Court last month.

But some say the rent-stabilization law itself is vulnerable to a legal challenge — at least under a more conservative U.S. Supreme Court.

Just five years ago, the owner of a five-story Upper East Side brownstone appealed a lawsuit challenging the New York State law to the Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case. But if President Trump installs more conservative judges on the bench, some say that the law could be vulnerable.

“The basis for finding rent regulation constitutional is very, very shaky,” said real estate attorney Joshua Stein. “All you need is a couple more conservative justices on the court.”

The Albany crapshoot

Though cracking down on landlords usually has strong backing from tenant groups, some longtime activists say focusing on criminal harassment ignores the real problem.

Under current rent-stabilization laws — which allow landlords to drastically increase rents if they can achieve vacancies — harassment as a business model is still worth the risk, argued Tenants PAC’s McKee.

“There’s always been this tendency to say, ‘We’re going to increase the penalties for harassment’ or ‘We’re going to go after people more vigorously,’” McKee said.

“It really frustrates me to see elected officials talking about this when they’re ignoring the need to close the loopholes in the rent laws, without which you would have a lot less harassment,” he said, citing methods like decontrolling units when tenants move out and making improvements to units to push rent over the so-called luxury threshold. Those tactics have allowed landlords to destabilize tens of thousands of units.

State Senator Liz Krueger, who co-sponsored Schneiderman’s bill, told TRD that there is an “enormous correlation” between loose rent-stabilization laws and tenant harassment.

She said that for landlords, turning over units is tantamount to “winning the lottery.”

For years, Krueger’s constituents on Manhattan’s East Side have complained of harassment from landlords but have had little success in court because they weren’t able to prove it.

Nonetheless, Schneiderman’s bill faces an uphill battle in the Republican-controlled state legislature.

Since 2013, Brooklyn Assembly member Joseph Lentol has proposed very similar legislation — with less severe penalties. Same goes for Upper West Side Assembly member Linda Rosenthal, a rent-stabilized tenant herself.

Neither of those proposals has gotten anywhere.

“I think [Schneiderman] still runs up against the same math in the Senate,” Rosenthal said, referring to the ratio of Democrats to Republicans. “I think coming up this year we’re going to be passing a whole slate of tenant-protection bills in the Assembly. None of them will get a hearing in the Senate.”

Krueger said she’s hopeful the bill she’s pushing with Schneiderman will be heard in the next session.

“The existing civil and city harassment laws are clearly not strong enough to get anyone to change their behavior,” Krueger said. “And laws that don’t actually motivate people to stop doing bad things aren’t very effective laws.”

Meanwhile, the AG’s office still has a civil tenant-harassment case pending against Croman.

A former Croman employee, who requested anonymity because he did not want to be mentioned in an article about his disgraced former boss, said many landlords are willing to pay civil fines if they know they can make millions by kicking out tenants. “It’s kind of like you’re driving a car. You know if you park and go to Starbucks you’re going to get a ticket. But it’s just a ticket.”

Correction: In a previous version of this story, TRD incorrectly stated that tenants, rather than the New York State Attorney General, had a pending civil case against Croman and characterized the case as difficult to win.