In 2007, Charles Murphy, a current partner at billionaire John Paulson’s hedge fund, Paulson & Co., bought a turn-of-the-century limestone mansion off Fifth Avenue from Seagram heir Matthew Bronfman. Murphy paid $33 million for the pad, which was a record price for a New York mansion less than 26 feet wide at the time. Then, in 2016, he put the property back on the market for $49.5 million, evidently envisioning a windfall.

But the home at 7 East 67th Street didn’t sell — even after listing broker Carrie Chiang of the Corcoran Group slashed the price by more than $10 million. Murphy pulled the listing, but the townhouse reappeared last month with a further discounted price of $36.5 million. Assuming the hedge funder can find a buyer for that amount, factoring in broker and attorney fees, he will hardly clear the sum he paid a decade ago.

For Murphy, who had worked at another hedge fund, the Fairfield Greenwich Group, when it invested more than $7 billion with Bernie Madoff, the luxury home may turn out to be another poorly timed investment.

While the hedge funder declined to comment for this story, industry insiders say his situation is hardly unique in a market where townhouses are lingering for much longer than they did even a year ago — and selling far below their ambitious asking prices. As New York’s condominium market becomes increasingly oversupplied with large, luxurious four- and five-bedroom apartments, wealthy buyers are spoiled for choice. In turn, the market for townhouses is quickly cooling off.

After a long bull run, the niche market, which represents just 2.5 percent of all Manhattan sales, is finally past its peak, brokers say.

“You’re seeing townhouses languishing,” said Elizabeth Ann Stribling-Kivlan of Stribling & Associates. “The townhouse used to be the ultimate trophy and status symbol, but the prices aren’t as extraordinarily high as they were in the past.”

Indeed, the numbers, which had rallied higher and higher from 2010 onward, took a tumble in 2016.

The median sales price for a Manhattan townhouse fell by 5.3 percent last year to $4.97 million after several years of consecutive increases, according to a recent report from brokerage Douglas Elliman. The previous year set a record with a median recorded price of $5.25 million. The average price per square foot for a home also declined in 2016 by 8.1 percent to $1,592 a foot.

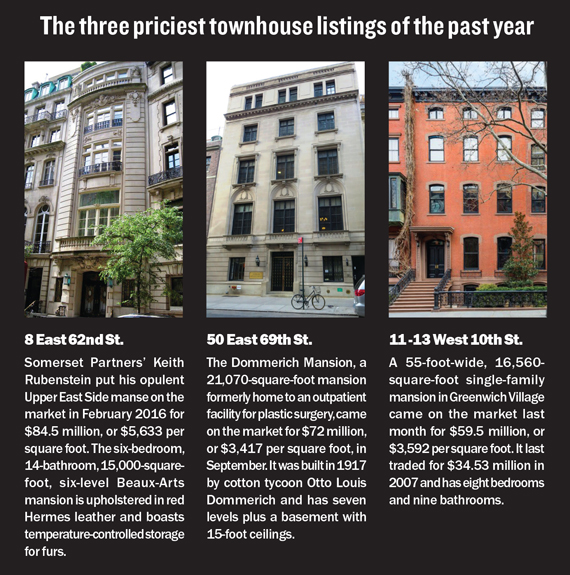

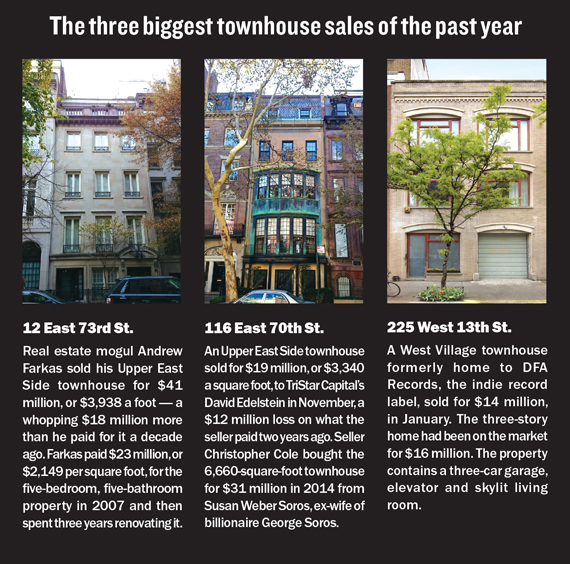

There have been some positive signs for sellers in recent months. A Chinese conglomerate is rumored to be in talks to buy a more than 20,000-square-foot house owned by the Wildenstein family at 19 East 64th Street for $81 million. And, perhaps most notably, real estate bigwig Andrew Farkas sold his townhouse at 12 East 73rd Street for $41 million in February, an $18 million profit over what he paid in 2007.

Brokers, however, warned that the Farkas deal was more the exception than the norm. In general, “it feels like most things are selling at least 20 percent less than they would have even two years ago,” said townhouse broker Jed Garfield of Leslie J. Garfield & Co.

Sellers are certainly showing more willingness to negotiate, especially given how long townhouses are now sitting on the market. The number of days a property spent on the market averaged 164 in 2016, up by 47 percent from the previous year. That put the townhouse absorption rate at 16 months, down by about 15 percent from 2015. Meanwhile, the average listing discount — the difference between the asking and final sale price — tripled to 10.7 percent from 2015 to 2016, reflecting sellers’ increased willingness to compromise on price.

Arthur Becker, a finance executive who traded his investment in a Soho condo project at 10 Sullivan Street last year for three adjacent townhouses, said patience is a virtue. He’s looking to sell all three and had put the first, 50 Sullivan, on the market for $17.25 million.

Late last month, Becker lowered the asking price on the 25-foot-wide townhouse to $16.75 million, or $2,791 a foot. The property, designed by architect Cary Tamarkin, has four bedrooms and four bathrooms.

“I don’t think two years is unrealistic,” Becker, perhaps best known for his former marriage to wedding-dress designer Vera Wang, said of the time frame in which he expects to sell the properties. Patience comes naturally “when you can’t do anything else,” he added.

The mood of the market is a world away from the highs of just three years ago, when the nation of Qatar came close to inking a $90 million deal to buy the Wildenstein townhouse on East 64th Street. The deal would have been the city’s priciest commercial townhouse deal ever.

The mood of the market is a world away from the highs of just three years ago, when the nation of Qatar came close to inking a $90 million deal to buy the Wildenstein townhouse on East 64th Street. The deal would have been the city’s priciest commercial townhouse deal ever.

Between 2013 and 2014, the median townhouse price rose 30 percent to $4.1 million, while the average price jumped more than 50 percent to $5.9 million, according to Elliman. Fueling the townhouse frenzy was the relative difficulty of pricing townhouses in comparison with condos and co-ops. Since so few townhouses sell each year, comps can be wobbly, sources said.

In recent years, though, sellers became trigger-happy and prices kept climbing, beyond what buyers were willing to pay, said appraiser Jonathan Miller, who prepared the Elliman report.

Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim listed his Manhattan mansion at 1009 Fifth Avenue for $80 million in 2015 after paying just $44 million five years earlier. And a turn-of-the-20th-century townhouse at 24 East 81st Street, owned by a family tied to the real estate firm Centaur Properties, listed for $60 million that same year.

Agents scoffed at the price of the 81st Street property when it came on the market. One said on the condition of anonymity that any buyer would have to be a fan of the dead, since the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel is located just across the street.

In some cases, sellers have been forced to chop their initial asking prices by more than half. Designer Juan Pablo Molyneux originally listed his townhouse at 29 East 69th Street for $48 million — a price that eventually got whittled down to $22.5 million before the property sold.

“There was no arithmetic conversation to have about the value of that piece of real estate,” said Garfield, who was not involved in the sale. “When you have something that’s so expensive relative to market, no one even looks at it. People just say, ‘That’s not real.’”

Even for the most audacious brokers, some of the figures became problematic.

“We, as brokers, have to give owners high numbers,” Garfield added. “That’s how you get the business 99 percent of the time. But some of these were just ridiculous.”

An added complication for townhouse sellers is that condos, by comparison, now offer too much. Developers who rushed into the market a few years before it peaked typically built larger, family-sized units with four or five bedrooms apiece. Those units compete directly with townhouses and, now that condo prices are dropping amid a supply surge, they provide more bang for the buck.

That really changes the “primary impetus for buying a house, which was that you got more space,” Garfield noted.

The cooling of the townhouse market has also been spurred by the increased costs of renovating the houses, said luxury broker Donna Olshan of Olshan Realty. With so much ongoing construction in the city, the contractors that are available charge more. A run-of-the-mill townhouse renovation can cost $4 million to $5 million, she estimated.

“I have seen clients quoted renovation costs 25 percent higher than two to three years ago,” Olshan said. “In a blink of an eye, costs can get racked up beyond the imaginable.”

But as the broader New York City real estate market comes to terms with the end of a robust cycle, it seems the townhouse sector is having its own mini-correction.

Indeed, the scandal-plagued billionaire Guy Wildenstein, who was recently embroiled in a tax scandal in France, chopped $10 million off the asking price for his own double-wide townhouse at 7 Sutton Square in December, bringing the asking price to $48.5 million. And both the Slim mansion and the East 81st Street townhouse have been taken off the market.

“Townhouses are the classic example of the aspirational-pricing phenomenon,” Miller said. “The townhouse market tends to skew high on prices, and the higher you go in the resale market, the higher the instances of aspirational pricing.”