One57, the first of the glassy giants to rise on 57th Street, wasn’t Lendlease’s key to Billionaire’s Row — it was a 60-story residential project on West 42nd Street.

Roughly a decade ago, Extell Development tapped the Australian construction company to build the Orion, a 551-unit condominium building. That gig led to additional jobs for Gary Barnett as he grew his luxury empire. And in a matter of a few years, Lendlease became one of the go-to contractors for high-end condo construction in New York City.

“That good work paid off when those developers acquired trophy sites overlooking the park,” said Ralph Esposito, who heads Lendlease’s construction operations on the East Coast.

The contractor has completed construction on most of Billionaires’ Row, including Harry Macklowe and CIM Group’s 432 Park Avenue, World Wide Group and Rose Associates’ 252 East 57th Street, Vornado Realty Trust’s 220 Central Park South and Hines’ 53 West 53rd Street.

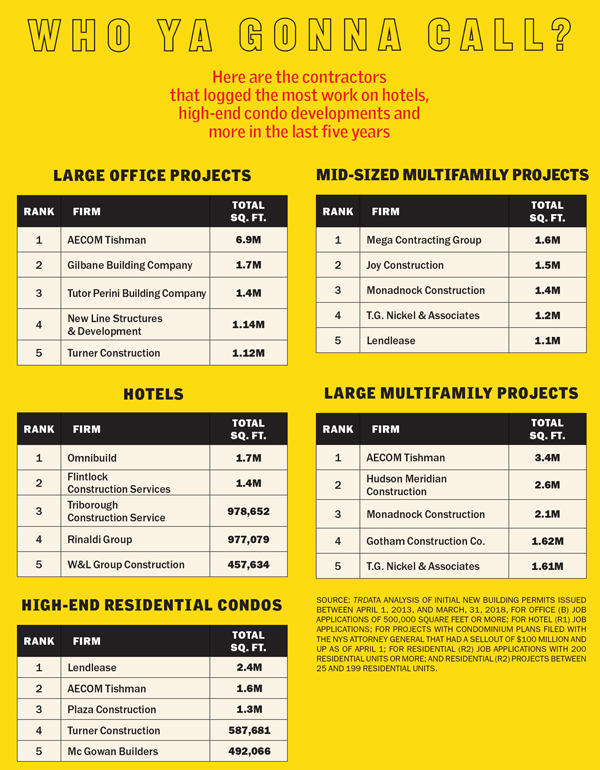

Other general contractors have carved out their own niches in New York’s sprawling real estate industry. AECOM Tishman, for instance, has dominated office development over the past five years, while Omnibuild and Flintlock Construction have been the city’s most prolific hotel builders.

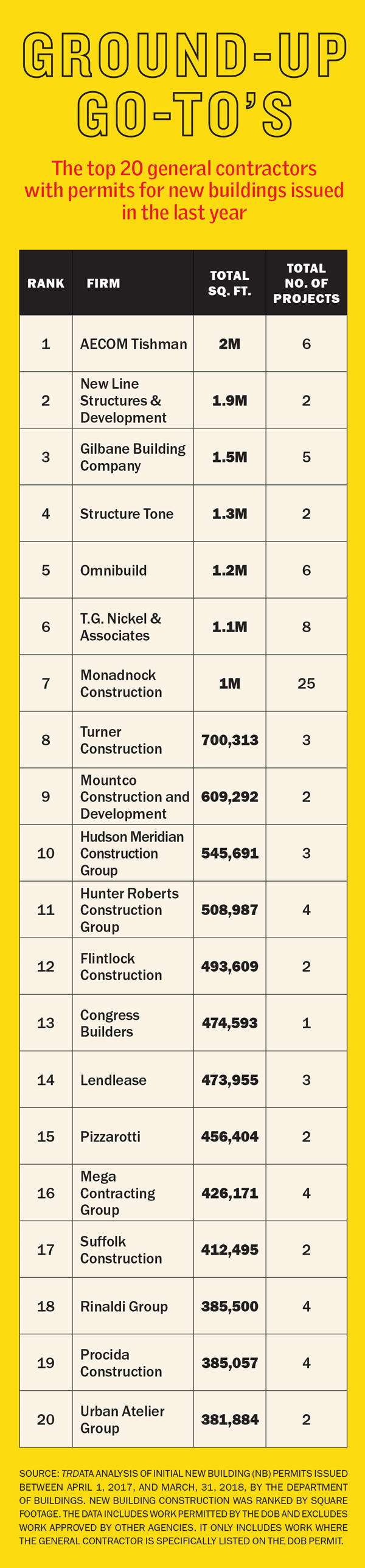

This month, as construction firms ride out the wave of the last development boom, The Real Deal reviewed hundreds of permit applications filed with the city’s Department of Buildings to determine which companies lined up the most new work across the five boroughs in the past 12 months. The results are an update of TRD’s ranking last year, which reflected a five-year look back at the top contractors for new buildings and renovations.

AECOM Tishman topped the list of the 20 most active companies doing ground-up construction with 2 million square feet of new permits issued between April 1, 2017, and March 31, 2018. New Line Structures & Development took the No. 2 spot with 1.9 million, and Gilbane Building Company followed in third place with 1.5 million. Structure Tone and Omnibuild rounded out the top five with 1.3 million square feet and 1.2 million, respectively.

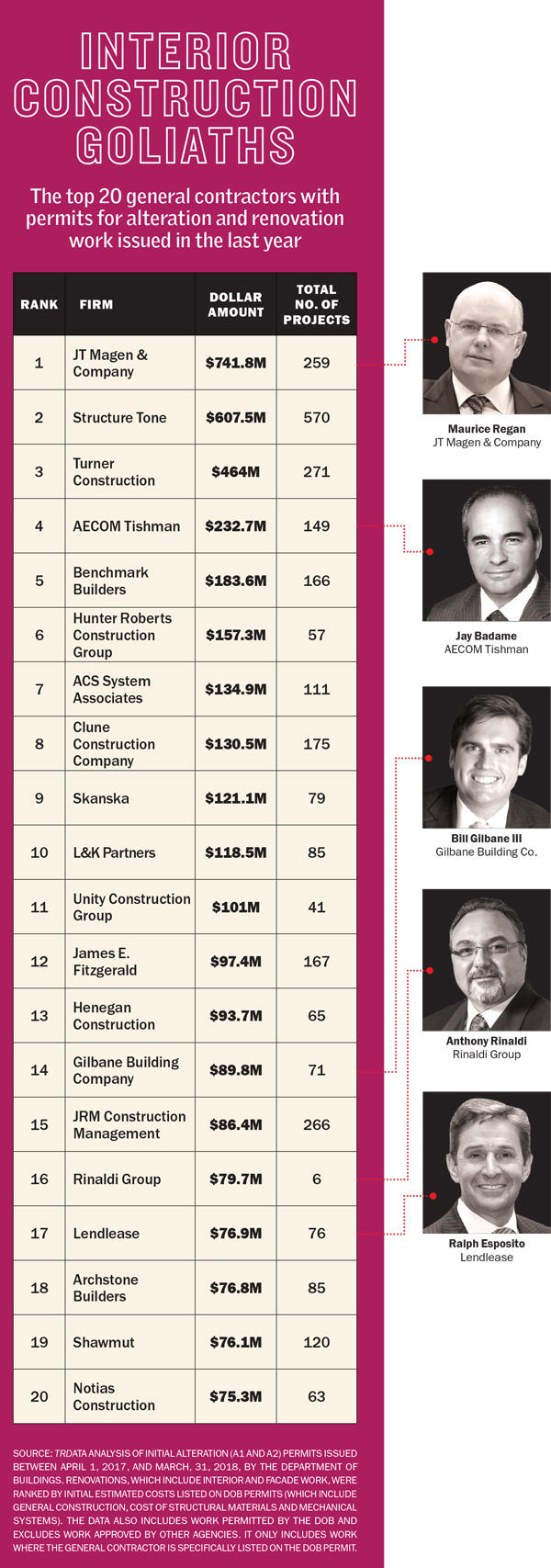

When it came to alteration and renovation work, some of the same firms dominated our ranking. JT Magen & Company took first place with $741.8 million worth of work, followed by Structure Tone with $607.5 million and Turner Construction with $464 million. AECOM Tishman and Benchmark Builders took the No. 4 and No. 5 spots with $232.7 and $183.6 million, respectively.

When it came to alteration and renovation work, some of the same firms dominated our ranking. JT Magen & Company took first place with $741.8 million worth of work, followed by Structure Tone with $607.5 million and Turner Construction with $464 million. AECOM Tishman and Benchmark Builders took the No. 4 and No. 5 spots with $232.7 and $183.6 million, respectively.

And collectively, the top 20 ground-up builders received new permits for 16.3 million square feet of work in the past year, while the top 20 firms doing interior work filed plans for $3.75 billion worth of projects.

To be successful, these companies must strike a difficult balance: Avoid being pigeonholed while also being perceived as an expert in specific fields. There’s also considerable pressure for leading general contractors when it comes to whether they choose union or nonunion labor. Battles over developers’ use of mixed workforces have become increasingly vitriolic and public, serving as a stark reminder that some in construction remain resistant to change.

Meanwhile, the industry is coping with its share of graft: Last October, the offices of Turner Construction were raided as part of an alleged overbilling scheme. Then, in April, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. announced indictments against several engineering companies and a former official with the city’s Department of Environmental Protection in connection to a $165 million bribery scheme. The official allegedly provided early information on public projects to the companies to give them an edge in exchange for work being funneled to subcontracting companies formed by the official.

“New York City is like the Titanic when it comes to its construction history,” said Richard Wood, CEO of Plaza Construction. “It’s a big ship that’s moving in one direction, and when there’s an iceberg, it has a hard time missing it.”

King of the hill

Having expertise in a highly specialized field — whether it’s building ultra-luxury skyscrapers or renovating prewar townhomes — gives a general contractor an edge when initially bidding on a development. It also proves beneficial when trouble arises mid-project.

Last year, Macklowe swapped Gilbane for JT Magen on his office-to-residential conversion of One Wall Street. The challenge was that the project required an extensive reconfiguration of the building’s layout and a deep understanding of prewar construction, said Maurice Regan, president of JT Magen, a Manhattan-based firm with 350 employees and offices in Chicago and Los Angeles.

Last year, Macklowe swapped Gilbane for JT Magen on his office-to-residential conversion of One Wall Street. The challenge was that the project required an extensive reconfiguration of the building’s layout and a deep understanding of prewar construction, said Maurice Regan, president of JT Magen, a Manhattan-based firm with 350 employees and offices in Chicago and Los Angeles.

There are common design elements and vulnerabilities in these buildings that need to be addressed before a massive overhaul. For instance, JT Magen was adding another floor to such a building, but the existing steel in the roof was rusted to the point where additional weight would have collapsed the entire structure. “Having these surprises rear their ugly head in the middle of a project can be very costly,” Regan said.

Older buildings also tend to feature single-paned, energy-sucking windows, along with asbestos and lead paint. The location of bathrooms in a building — like in a hotel, where all the bathrooms are typically stacked on top of each other — can make leaks and mold more likely, Regan said. If contractors don’t anticipate these challenges, the results can be “devastating,” he noted.

With such importance placed on construction firms’ specialties, TRD also set out to find the top performing general contractors in specific markets by poring over permit applications filed with New York’s DOB from April 1, 2013, to March 31, 2018.

“If I have a heart problem and I need a doctor, I want to go to one who has dealt with that more than anyone else,” said Jay Badame, head of AECOM Tishman’s New York office. “I don’t want to go to someone who is just putting their training wheels on.”

In addition to dominating office construction, Tishman is billed as an expert on high-end condo projects. The company took second place on TRD’s list of general contractors building condos with projected sellouts of $100 million or more with nearly 1.6 million square feet of work. Lendlease topped that ranking with 2.4 million square feet, while Plaza Construction took third place with 1.3 million, followed by Turner with 587,681 million and Mc Gowan with 492,066.

But as the luxury market softens and fewer condo projects are on the horizon, construction firms are taking cues from their clients and finding other types of developments to take on. Last year, there were 305 plans filed for new condo buildings with either 5,000 square feet or five or more residential units across all five boroughs, according to filings with the Attorney General’s office. That’s down from 330 in 2016.

“The theme in the last year and looking forward has certainly been fewer condos — perhaps fewer market rate,” said Greg Bauso, president of Brooklyn-based Monadnock, which took the No. 7 spot on TRD’s ranking of general contractors doing ground-up construction. “We basically have no condo work in the backlog now.”

The largest construction companies rake in a significant volume of work across multiple asset classes. Lendlease, for instance, also ranked among the top five companies doing large and mid-size multifamily projects. Lendlease’s Esposito said that the firm also does a lot of hospital work, counting NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital and New York University Langone Medical Center among its clients. He said that large institutions often pose less of a credit risk than private developers.

“The work is very predictable. It’s not as volatile as condominium starts,” he said. “The institutions have very good policies and procedures, you always know you are going to get paid.”

Tishman — which has handled the bulk of construction work at the World Trade Center and is managing Brookfield Properties’ Manhattan West — took the top spot for new office projects that span 500,000 square feet or more, logging 6.9 million square feet. Gilbane Building Company ranked second with 1.7 million, followed by Tutor Perini Building Corporation with 1.4 million, New Line Structures with 1.14 million and then Turner with 1.12 million.

In addition to prewar residential building renovations, JT Magen does a lot of office and retail work; it was hired to build out spaces for Nordstrom, Adidas and Nike on Fifth Avenue.

And Turner was recently tapped to lead construction of Tishman Speyer’s the Spiral at 509 West 34th Street, a $3.2 billion office tower that will span more than 2.2 million square feet. Turner did not return multiple messages seeking comment. That project is not reflected in this ranking, since the new building permits haven’t been issued yet.

“All our eggs are not in the residential basket,” Tishman’s Badame said. “We make sure that we touch all those [other asset classes], such that if work slows down, we can transfer out talents.”

Quiet giants

Smaller or less-known firms emerged as the dominant players in the hotel and mid-sized multifamily markets.

For mid-sized multifamily projects, with 25 to 199 units, a few affordable housing builders topped the list. Mega Contracting Group, an Astoria-based firm that does a lot of supportive and affordable housing work, was the No. 1 contractor, with 1.6 million square feet. Joy Construction, which also builds a lot of work in the sector, ranked second with 1.5 million. Monadnock ranked third with 1.4 million square feet, followed by T.G. Nickel & Associates with 1.2 million square feet and Lendlease with 1.1 million.

Some of the larger firms popped up again when it came to multifamily projects with 200 units or more. On that list, Tishman clocked in at No. 1, with 3.4 million square feet. Hudson Meridian Construction took the No. 2 spot with about 2.6 million square feet. Monadnock Construction took third place with 2.1 million, followed by Gotham Construction with 1.62 million and T.G. Nickel with 1.61 million.

The multifamily market also saw an uptick in new permits issued for ground-up projects in 2017; there were 765, up from 724 the year prior, according to a TRD analysis of DOB filings.

But despite strong demand, some are still worried about the multifamily sector. Monadnock’s Bauso, whose firm is working on several affordable multifamily projects, including La Central at 626 Bergen Avenue in the Bronx and two supportive housing buildings at Related Companies’ Marine Terrace complex in Astoria, said cost is a tremendous challenge. (Monadnock has its own development arm, but a majority of the construction it does is for third parties.)

“Land costs are still expensive, which is forcing developers to push down on construction costs as much as they can,” Bauso said. He noted that general liability insurance and worker’s compensation typically account for 8 to 12 percent of a project’s cost.

“That’s literally more than double what it was 10 years ago,” Bauso said. “The insurance market has not softened at all, and that’s a problem.”

Meanwhile, the hotel market — which for years has struggled with dropping revenues and oversupply — is finally showing some signs of promise. Average revenue declined at a slower pace last year, and demand appears to be on the rise. The number of new hotel rooms slated to open in 2018 is 7,802 — the highest number seen since at least 2000, according to hospitality research firm STR.

The number of new permits issued for such projects fell to 36 in 2017, down from 45 in 2016. And the number of permits issued for hotel renovations dropped steeply to six in 2017 from 12 the previous year.

Omnibuild led the pack of general contractors that scored the most hotel work in the past year, logging 1.7 million square feet of new product. Flintlock took second place with 1.4 million square feet, followed by Triborough Construction Service, Rinaldi Group and W&L Group Construction.

Anthony Rinaldi, head of the Secaucus, New Jersey-based Rinaldi Group — which raked in 977,079 square feet of new hotel work in 2017 — said he hasn’t seen a decrease in demand for the product.

“I keep hearing that the market is oversaturated with hotels,” he said. “I am reading about it, I am hearing about it, but I’m not seeing it.”

Instead, Rinaldi — who is also the New York City regional chair of the Associated Builders and Contractors, which represents nonunion construction shops — pointed to the shortage of skilled labor and rising costs as the biggest concerns for general contractors across the board.

In fact, construction costs in the city rose 3.29 percent from January 2017 to January 2018, according to the latest report by construction consultancy firm Rider Levett Bucknel.

“Guys are so busy that many of them aren’t bidding on new work,” Rinaldi said. “You wind up having fewer and limited volume of trades to go to, and that creates a difficulty, and it also creates a price-point battle.”

The cost conflict

In addition to both specializing and diversifying, construction firms must always have an eye on cost to stay competitive in New York. At the same time, it’s increasingly difficult to find skilled labor in certain trades.

A 2017 national survey conducted by Dodge Data & Analytics, construction materials manufacturer USG and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce found that 61 percent of contracting companies are having difficulty hiring workers in certain trades, including concrete, masonry, plumbing, interior finishes and electrical. One-third of the contractors surveyed reported that they had turned down work to keep up with project volume.

Bill Gilbane III, the senior vice president of Gilbane’s New York office, said that while a slowdown has been predicted in certain markets, companies are still riding the wave of the last boom. He noted that the real threat to contractors in such a busy, labor-strapped time is taking on more work than they can handle.

“Everybody keeps waiting for this slowdown that doesn’t appear to be coming,” he said. “It’s counterintuitive, but more people go out of business when the market is good because they take on too much.”

Open shops in particular fell victim to that fate, according to Michael Cusack, managing director of Alliant Insurance Service’s construction services group. He said the open shop market “exploded” around the opportunities presented in the high-rise residential market, but the companies weren’t necessarily prepared for the volume of work.

“The open-shop firms are a little less mature than the established union players,” he said. “And I think there’s some growing pains in managing all of the opportunities before them.”

Cusack said contracts are also increasingly skewing in favor of owners rather than construction managers. One way this is happening is through liquidating damages — what the contractor pays for failing to finish a project on time or for some other serious breaches. Cusack said extraordinarily high liquidating damages have crept into contracts, driving up a construction manager’s daily costs by anywhere between $200,000 and $500,000.

The makeup of subcontractors hired for a project also plays a significant part in staying competitive. Developers are increasingly opting to hire both union and nonunion labor for their projects to cut down on costs, and the change has dramatically shifted the balance of residential work. (It’s believed that well over 50 percent of residential work in the city is done through open-shop labor.)

Tishman’s Badame rattled off a few trades that have been more progressive than their counterparts — carpenters, sheet metal workers and steamfitters — by, among other things, adding more workers who are paid at a lower rate than skilled journeymen. He wouldn’t identify which trades aren’t as willing to find ways to decrease labor costs.

This topic has ignited an ugly battle between the Related Companies and the Building and Construction Trades Council. The powerful union group has been protesting the developer’s decision to go open-shop for the second phase of Hudson Yards. And in March, Related filed a lawsuit against the organization and its president, Gary LaBarbera, alleging that it’s inflated construction costs at the project by more than $100 million. Notably, the New York City District Council of Carpenters has stayed out of the squabble — unlike some trades which have vowed not to work on the megadevelopment unless Related changes course — and has continued to work on the office tower at 50 Hudson Yards.

“The Building Trades are feeling the pressure. I think they know they are losing New York City, and I think they are almost at a point where they’ve lost NYC,” Rinaldi said. “When you have developers like Related deciding to go [open shop], I think that has a major impact on the unions.”

The case seems to be a flashpoint in the union’s struggle to maintain ground in the city. Plaza Construction’s Wood said that there have been some successful negotiations with the BCTC in trying to find ways to stay competitive — such as work rule changes and reductions in benefit packages — but said there’s still a long way to go.

“They’ve accumulated this way of doing business over a 100 years,” he said. “It’s tough to make these changes.”