As the early aughts unfolded, the notoriously mercurial real estate mogul Sheldon Solow waged one of his characteristically deep-pocketed legal battles over a Manhattan ground lease.

Solow [TRDataCustom] claimed that a group of sellers — including the British billionaire brothers David and Frederick Barclay — had fudged the value of the lease to trick him into overpaying for the interest at 380 Madison Avenue.

The courts, however, dismissed Solow’s claim as frivolous and awarded $1.3 million to the Barclays.

“He was an extraordinarily aggressive litigant,” said Jerome Katz, senior counsel at the global law firm Ropes & Gray, who represented the brothers. “He had the misfortune, however, of running into an equally aggressive and equally well-heeled litigant in my client.”

That kind of developer battling is nothing new, of course. It dates back to the earliest days of Manhattan land trades in the 1600s.

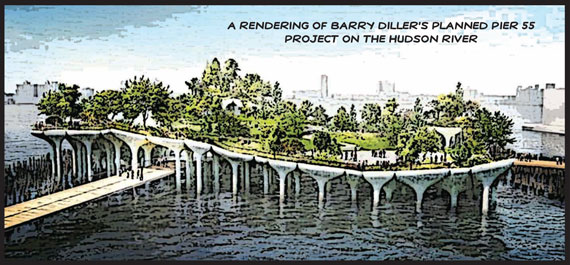

But the recent heated exchange between two of the industry’s biggest moguls — media giant Barry Diller, who is developing a floating park over the Hudson River, and real estate dynasty patriarch Douglas Durst — have put a glaring spotlight on just how nasty these battles can get.

In that dispute, which was still unfolding in the press last month, Durst allegedly quietly bankrolled a lawsuit to destroy Diller’s park, while Diller called the Durst family a “killing machine,” a term he later apologized for.

In a city full of big checkbooks and even bigger egos, it’s no surprise that the titans who shape the skyline play to win — and hate to lose.

“Conflicts and feuds are part of our industry’s fabric, some obviously more high-profile than others,” said Eastern Consolidated CEO Peter Hauspurg, noting that his firm has internal rules to address conflicts between brokers. “Outside, however, in the wide-open spaces of the New York City battleground, no such rules apply.”

Real estate is by no means the only industry where powerful provocateurs publicly lock horns.

Finance titans Bill Ackman and Carl Icahn have repeatedly sued each other and publicly called each other names that might be invoked in a high school cafeteria.

But fights over “tangible assets are easier to understand than battles between lawyers [or] financial firms,” said Partnership for New York City President Kathryn Wylde, who counts many of the city’s business leaders among her group’s members.

She added that heads of private companies — of which there are many in real estate — have more leeway when it comes to mudslinging with competitors. “People who run public companies don’t have the luxury of getting into personal tiffs,” Wylde said.

These personal tiffs — which in addition to name-calling and secret lawsuits have involved ordering up newspaper hit pieces and physical attacks — can have a major impact on properties and portfolios worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Below is a look at some of the current and past battles royal among NYC’s titans.

Secret vendettas

The headline said it all: “Clash of the Titans? Fight Against Park Has Secret Backer, Media Mogul Says.”

In September, the New York Times broke the grudge-match story of the year, in which Diller accused Durst of financing a legal campaign to stop his efforts to build the $200 million, 2.7-acre floating park on the Hudson River known as Pier 55.

Among those who follow the city’s power brokers, the story was delicious, providing insight into the politics of philanthropy as well as control over NYC’s prized public spaces. Then last month, during an event hosted by Vanity Fair, the gloves really came off.

In an interview with famed Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter, Diller spoke about how he discovered that Durst was behind the legal actions taken by the City Club of New York, a civic group that sued the Hudson River Park Trust, which is spearheading Pier 55.

“I couldn’t figure it out until I found out … three people [behind the lawsuit] — one of whom was named Durst from the very honorable Durst family killing machine,” he said.

Carter immediately interjected, “No, that’s one member — Robert Durst.”

Diller’s response: “He should have killed his brother.”

Back in New York, Douglas Durst stayed tight-lipped, refusing to get into a war of words with a fellow mogul, but the City Club blasted the “arrogant and self-absorbed Diller” and demanded an apology.

Durst declined to comment for this story, and in a statement provided to The Real Deal by a spokesperson for Diller’s company IAC, Diller apologized for his “intemperate remark.” He added, “Of course I didn’t mean it, but nevertheless it was reckless and wrong.”

For now, it looks like the Pier 55 project is moving forward. Late last month, the state Court of Appeals dismissed the City Club’s lawsuit. The nonprofit, though, plans to file a legal challenge on the federal level.

Still, the opposition to the park seems at odds with Durst’s image as a prominent civic leader. And the alleged surreptitious legal maneuver calls to mind a similar strategy employed by Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel, who secretly funded the legal battle waged by the professional wrestler Hulk Hogan that financially ruined the gossip website Gawker.

Real estate attorney Adam Leitman Bailey characterized the Diller-Durst feud this way: “Some people just have a lot of F-you money.”

Old grudges die hard

Back in 2010, Stephen Ross, the head of the Related Companies, and Moinian Group CEO Joe Moinian traded barbs as they wrestled for control of 3 Columbus Circle.

Moinian was struggling to restructure the $250 million mortgage on the 26-story building — one of the crown jewels in his commercial portfolio — when Related (which owned the note with Deutsche Bank) moved to foreclose.

Moinian was struggling to restructure the $250 million mortgage on the 26-story building — one of the crown jewels in his commercial portfolio — when Related (which owned the note with Deutsche Bank) moved to foreclose.

The move was particularly aggressive for Ross, who had just come off a two-year stint as chairman of the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), serving as a figurehead for the industry.

“It really did get personal,” said attorney Jonathan Mechanic, whose real estate group at Fried Frank Harris Shriver & Jacobson advised Moinian in a $500 million joint venture with SL Green Realty that helped the developer retain control of the building.

“The negotiations really got heated, especially when you’re in a distressed situation,” he added. “There were some missed opportunities to make some kind of negotiated transaction.”

Related paid close to face value for the debt, making it clear that it believed the property was worth more than the debt and sending a signal that a hostile takeover was possible. To add salt to the wound, Related didn’t even want to keep the building, which Moinian was spending $175 million to renovate. Rather, Related planned to tear it down and erect a new tower to house a Nordstrom store at its base with apartments on top.

Ross was not shy about his plans, discussing the deal on CNBC’s “Squawk Box.” “We saw … that there is a higher and better use for the property, and we bought the note and are hoping to do something there,” Ross said on the show.

Moinian fired back with a $200 million lawsuit that accused his rival of trying to “steal” the building.

He was ultimately rescued when SL Green helped him pay Ross $278 million, but the feud didn’t stop there. Ross took a jab at Moinian in the press, telling the New York Times he thought Moinian’s redevelopment amounted to an “ugly building.”

“You can’t create a silk purse from this sow’s ear,” he said. “It’s unfortunate for his creditors.”

When Ross offered $150 million for the property, Moinian’s response was to ask if he could buy Related’s Time Warner Center and tear it down.

Sources say the wound is still fresh, particularly for Moinian.

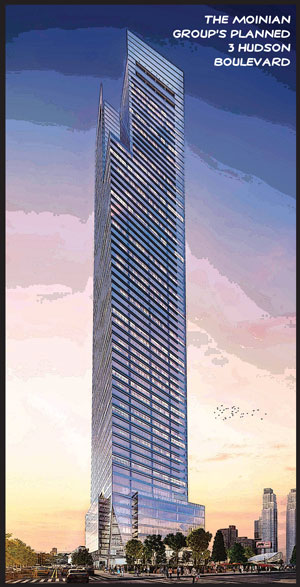

Today, the two are going up against each other on the Far West Side, where the Moinian Group is planning a 1.8 million-square-foot tower known as 3 Hudson Boulevard across the street from Related’s massive mixed-use Hudson Yards site.

When Moinian started the office leasing effort for the tower in 2013, he had aimed to land an anchor tenant and have the building completed by 2016. But three years later, he has yet to land an anchor tenant (or any other tenant) and cannot move forward with full-blown construction. That’s even as Related has locked in a slew of tenants across multiple buildings.

And Moinian is now in danger of being overshadowed by another neighboring project: Tishman Speyer’s planned $3 billion, Bjarke Ingels-designed office tower next door.

For years observers have speculated that Moinian may one day sell the site — similar to the way Extell Development’s Gary Barnett sold his shrewdly named One Hudson Yards site to Related in 2013 for $168 million. But Moinian told the New York Post last month that the site is “absolutely not for sale,” even though he gets “offers all the time.”

Sources familiar with the Ross-Moinian relationship, however, said that those offers probably have not come from Related, given the bad blood between the two.

Partnerships gone sour?

While many grudges are well known among industry players, others are only whispered about.

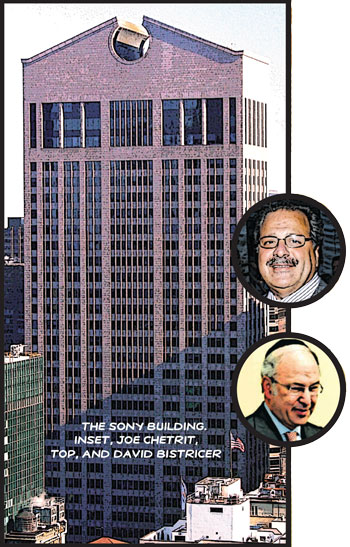

That may be the case with developers David Bistricer and Joe Chetrit — who have frequently partnered on high-profile deals and projects.

That may be the case with developers David Bistricer and Joe Chetrit — who have frequently partnered on high-profile deals and projects.

All public appearances suggest that their relationship is going swimmingly.

The duo first teamed up in 2007, to buy the Brooklyn Hospital Center for $15.6 million. Since that time, they have made six other big buys, including the $180 million Flatotel on West 52nd Street and, of course, the former Sony Building at 550 Madison Avenue, which they bought in 2013 for $1.1 billion and then sold last year after scrapping plans for a luxury condo conversion.

But despite the seemingly lucrative partnership, the two have been fighting with each other behind the scenes, two sources told TRD. “They’re constantly bickering and at each other’s throats,” said a source familiar with the two moguls who asked to remain anonymous.

The allegedly strained relationship, sources said, could put stress on projects they’re working on together, such as the condo conversion of the Cabrini Medical Center in Gramercy, which listed its first units in September.

Bistricer became increasingly frustrated with Chetrit as he took longer to make decisions on their joint projects and was not happy when Chetrit became entangled in a Kazakhstani money-laundering scandal, according to the source.

Another major sticking point came with the sale of the Sony Building to the Olayan Group in June for $1.4 billion. Chetrit apparently wanted to sell the property and walk away with a neat profit rather than develop luxury condos in a potentially weak high-end residential market. Bistricer, on the other hand, wanted to develop. Sources say he tried to convince his partner to keep moving forward, to no avail.

“Joe pulled the trigger without his partner being fully on board. He just cut a deal and sold it,” the insider source said. “David was pissed.”

Chetrit emphatically denied that his relationship with Bistricer is even remotely strained. “David and I have a level of trust and respect for one another that is irrevocable,” he wrote in a statement to TRD. “We have been partners for seven years on various projects and continue to have a strong relationship.”

Bistricer said in a statement that, “Joe Chetrit is a partner that I work well with. His astute approach to business brings uncontested value to our many projects, which has led us to pursue dozens of opportunities together over the years. It is our complementary rapport that consistently leads to incredible business results.”

And indeed, the two still jointly own a portfolio they spent $450 million-plus collecting.

But if they are in fact warring, they wouldn’t be the only partners to have soured on each other.

Kevin Maloney once swore he’d never again work with Michael Stern.

Maloney’s Property Markets Group joined forces with Stern’s JDS Development in 2010 when they converted the former Verizon building at 212 West 18th Street into the successful Walker Tower condo.

After that success, the two teamed up on Stella Tower at 425 West 50th Street and on 111 West 57th Street, the Billionaires’ Row tower slated to be the tallest building in the hemisphere when it tops out in 2018.

But Maloney took umbrage when Stern started taking credit for the team’s projects in the press.

“It’s like dating someone. In the beginning everything is great, and then you start to see the cracks in each one of your relationships and you start to move away. There’s probably not a good fit here for us to work together going forward,” he said during a 2014 interview.

“I don’t know that it’s productive for any developer to stand up and get too much on his soapbox, saying look at all the great things I did,” he added, but then walked back his comments and said that PMG was “very pleased with our overall” partnership with JDS.

Time will tell how pleased (or displeased) the two truly are with each other. Another hit at 111 West 57th could, of course, influence whether they want to partner in the future. At the moment they don’t seem to have any other new deals in the works together.

Street fights

Fighting with words is one thing, but real estate battles sometimes get physical — or just plain dirty.

In one of the industry’s most notorious cases, investor Yair Levy bashed his partner Kent Swig in the arm with an ice bucket during a heated argument in 2008.

“We had a meeting about the Sheffield, and he started screaming and fighting with my lawyer. He stood up, and I said, ‘Sit down,’” Levy told TRD about the encounter in 2014. “He came at me and I grabbed the ice bucket to protect myself. He’s a much younger man — younger by 10 years. He got wet and I dropped the bucket. He tried to use it for publicity and make me out to be the bad guy.”

Levy pleaded guilty to harassing his partner and was sentenced to two days of community service, but he swung back with a lawsuit in 2009 claiming Swig siphoned off $50 million in construction funds from the Sheffield project.

It’s unclear what the dynamic between the two is today, as the men, who were poster children of the last bust, have remained largely out of the limelight and declined to comment.

But theirs is not the only heated dust-up to break news.

In March of this year, Related’s Ross and fellow developer Rob Speyer, the sitting chair of REBNY, nearly came to blows over the expired 421a tax abatement.

The incident — since dubbed the “Rumble at REBNY” by Crain’s New York, which first reported on it — took place during a meeting with some of the most powerful people in the industry.

When the meeting ended, the two began arguing and Speyer walked over to Ross, who jumped out of his seat before they were physically separated.

But they appeared to patch things up quickly. “REBNY meetings often feature passionate and frank exchanges, especially on issues as important as the future of affordable housing in New York City,” Ross and Speyer said in a joint statement to Crain’s. “And at the end, we always depart as friends and respected colleagues. Our most recent meeting was no different.”

A spokesperson for Speyer told TRD that at every meeting since, the two have made a point of sitting next to each other “because they think it’s important to show everyone that there’s no lingering hard feelings.”

Meanwhile, some titans have used — or attempted to use — their resources to take their competitors down a notch. One of those cases just recently came to light.

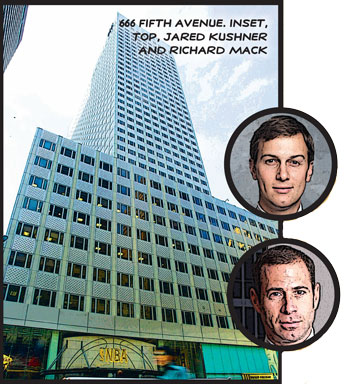

Kushner Companies CEO Jared Kushner ordered a reporter at the New York Observer, which he owns, to write a hit piece about fellow developer Richard Mack, according to a story in Vanity Fair that was corroborated by Elizabeth Spiers, the editor-in-chief of the Observer when Kushner assigned the story sometime in 2011 or 2012.

The animosity between the two traced back to negotiations over 666 Fifth Avenue, sources told TRD.

The animosity between the two traced back to negotiations over 666 Fifth Avenue, sources told TRD.

Kushner, who has recently been the subject of increased scrutiny for his role in the presidential campaign of his father-in-law, Donald Trump, was working with lenders to recapitalize the overleveraged 1.5-million-square-foot property. Sources said Mack — then an executive at AREA Property Partners, which was trying to acquire a slice of the tower’s debt at a discount along with several partners — objected to the young mogul’s strategy.

Kushner, who bought the tower in 2007 for $1.8 billion, eventually brought in Vornado Realty Trust as a partner and saved himself, but the ordeal “rubbed Jared the wrong way,” Spiers wrote in July. After the incident, Kushner passed along a negative tip about Mack. Spiers left the Observer in 2012 but wrote that she heard that Kushner later tried to resuscitate the story.

Family feuds

Feuds take on a very different (and often nastier) tone when they bubble up between relatives — a frequent reality in an industry peppered with family-run firms.

Brothers Paul and Seymour Milstein, for example, battled for years over a $5 billion family fortune.

By the time Seymour Milstein died in 2001 at the age of 80, it’s said, the once-inseparable brothers — who famously dined together daily at the Rainbow Room — were no longer speaking.

The case was settled in 2003 when the heirs to the fortune finally set aside their lawsuits and divvied up the assets.

More recently, in 2013, war broke out between members of the Feil family when the four heirs of late mogul Louis Feil battled for control of his $7 billion-plus portfolio.

“The binding of the book became loose when my father passed away,” Jeffrey Feil, who had been tapped to run the family business after his father died, told the Wall Street Journal in 2013, referring to his relationship with his siblings. “The pages fell out after my mother died.”

Today, the four Sitt brothers — Ralph, David, Jack and Eddie, who are titan Joe Sitt’s cousins — are engaged in their own ugly battle. The family infighting came to a head in 2014, when Jack sued Ralph, claiming he usurped control of the firm Sitt Asset Management and froze him out.

Then in 2015, brother Eddie filed a lawsuit claiming, among other things, that Ralph and David charged the company for excessive luxuries.

This past January, after a judge dismissed that suit, Eddie served family matriarch Marilyn Sitt with a demand letter — a legal document allowing him to continue with the suit — despite his earlier efforts to “protect her” from the sibling rivalry.

The latest turn of events came in May, when Eddie headed back to court with new allegations that his rival brothers were trying to dilute the shares he and Jack owned in the firm’s trophy tower at 2 Herald Square. That case is ongoing.

In another case where brotherly love was lacking, Frank and Michael Ring lost control of their 14-building Midtown South portfolio to Extell’s Barnett in 2014.

The brothers’ refusal to work together left them open to aggressive investors looking to get a piece of their prime portfolio, which had sat largely empty for years.

Barnett, quick to smell an opening, swooped in after Princeton Holdings got its claws on the portfolio. The deal has been a windfall for Barnett, who in 2015 flipped one of the properties, 212 Fifth Avenue, for $260 million — $170 million more than he paid.

Fried Frank’s Mechanic said that when partners — or relatives — can’t get along, “a host of value ends up being wasted.”

“If [the Ring brothers] had gotten along, all the value for Princeton and the further value for Barnett would have been reaped by the brothers,” he said.

In his 1991 book “Skyscraper Dreams,” which chronicles the city’s high-flying real estate business through several decades, Tom Shachtman put it this way: “When it comes to real estate, the great stories are all personal, but also all business.”

This story was updated to include a statement from David Bistricer.