When Jamie Hodari started looking for funding for his New York-based co-working startup, Industrious, in 2012, he didn’t even bother talking to venture capital firms.

“We were just so confident that VCs didn’t fund real estate that it wasn’t worth trying,” he said.

Instead, Hodari and his co-founder, Justin Stewart, went to anyone they knew — parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, friends — who had money and pitched them on investing in individual locations. While they managed to raise $8 million, it was tedious. They couldn’t sign a lease or get going on a project until they had every dime they needed in advance.

Then, all of a sudden, VCs started paying attention to real estate tech.

Between late 2016 and early 2017, Industrious raised $62 million in a Series B fundraising round led by Riverwood Capital, a private equity firm focused on high-growth tech companies.

When it started looking for another round of capital, it had a lengthy list of venture funds to talk to.

“You say, ‘here are the 64 funds I want to speak to’, and you do everything you can to [get] a warm introduction to those 64 funds,” he said. “You go to events. You have all of your key employees go on LinkedIn and figure out if they went to business school or college or grew up next door to someone who worked at one of them.”

Those efforts paid off, and in early 2018, Industrious landed a $80 million Series C round co-led by Fifth Wall Ventures, a venture fund focused entirely on real estate.

“It’s shocking how quickly the shift has happened,” said Hodari, who noted that it took the same amount of time to raise more than $140 million from institutions as it did to raise the initial $8 million.

“It’s shocking how quickly the shift has happened,” said Hodari, who noted that it took the same amount of time to raise more than $140 million from institutions as it did to raise the initial $8 million.

Industrious is just one of hundreds of real estate startups that have benefited as real estate venture investment — once a neglected backwater of the VC world — has exploded. In 2012, venture investment in real estate tech firms totaled just $44.7 million nationwide, according to research firm Pitchbook, which tracks public and private equity markets, including venture capital. In 2017, that jumped to a massive $5.7 billion.

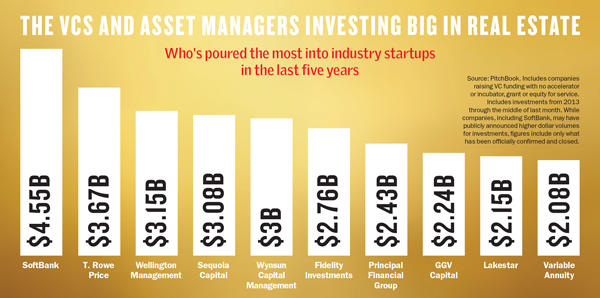

Giants in the space, like Japanese conglomerate SoftBank, have made national headlines for pumping billions into the industry (see chart). But sources say an even more remarkable trend is the emergence of VC funds exclusively devoted to bankrolling real estate startups. In addition to Fifth Wall, MetaProp, Camber Creek and others have all launched to capitalize on this sector. And JLL and RXR Realty have all also recently started funds.

Meanwhile, numerous family real estate companies have created their own venture capital vehicles, and existing VC firms that had long focused on other industries are now tripping over themselves to get in on the action.

“I don’t think there’s a whiteboard in San Francisco or the Valley right now that doesn’t have ‘real estate tech’ written on it,” said Ryan Simonetti, co-founder of office services startup Convene, which has itself raised $280.5 million.

But it’s the startups — which are announcing fundraising rounds at a dizzying pace — that often get the press attention. Less attention is paid to those bankrolling the ventures and to what it all means for the industry, which is now on the fast track for disruption.

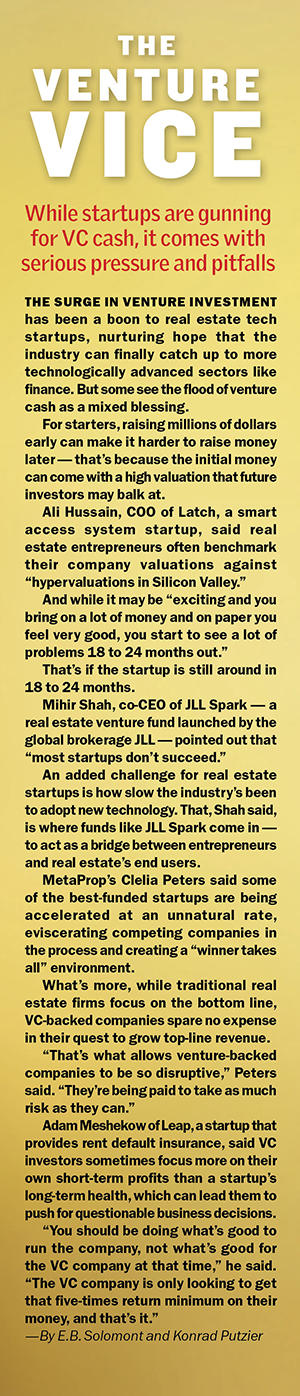

Brad Hargreaves, founder of the co-living company Common, said the money that startups are getting is “the most expensive capital you will ever find.”

Early-stage venture investors, he said, “are not going to be happy with less than a 10-times return.”

“You need to be prepared as an entrepreneur to take a big swing,” he said.

The VC blitz

The venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz made a name for itself as an early investor in Twitter, Facebook, Airbnb and dozens of other spectacularly successful startups. But with the exception of Airbnb, it paid little attention to real estate for years.

Then, in November 2016, the Silicon Valley-based firm invested in PeerStreet, a lending platform that allows laypeople to invest in real estate loans. And last year it led a $65 million Series C round for Cadre, the Kushner-backed company that invests in commercial properties and makes stakes available to investors. This year, it followed that up with big investments in home-selling platform Opendoor and blockchain startup Harbor.

For many investors, real estate is attractive because it’s littered with antiquated systems with room for improvement — whether the focus is on rental transactions, listings management, mortgage underwriting, data collection or services like co-living and co-working.

But without real estate backgrounds, many VCs have only recently started to understand this reality, especially when it comes to more complicated business-to-business commercial real estate products.

“The more esoteric the category, the harder it is for investors to get their arms around it,” said one venture capitalist, who asked not to be named.

The source said he’s increasingly interested in real estate investments — partly because there are more promising startups with more ambitious business plans out there than before and partly because rival VC firms are ramping up investments.

“If we go invest in a company in a Series A, part of what we’re betting on is that the company will do very well and that another firm will come along and put more money in,” he said.

In other words, these investments are creating something of a snowball effect: The more VC firms invest in real estate startups, the more likely it is that valuations keep rising and that VC firms can sell their stake for a profit. That, in turn, makes them more likely to invest in the first place.

“It actually helps the ecosystem dramatically when there are more players investing in it,” the source said. “That’s part of what I call the primordial soup, these conditions that need to exist in order for there to be this explosion of startups.”

Andreessen Horowitz is obviously not the only traditional venture capital firm that’s taken to real estate within the past few years.

Sequoia Capital, a VC giant in Silicon Valley, has invested $3.08 billion in real estate startups, including Airbnb and WeWork’s Chinese competitor UCommune, according to PitchBook. The Chinese venture firm GGV Capital and the European firm Lakestar have also invested more than $2 billion each. In addition, traditional asset management companies like T. Rowe Price and Wellington Management have also made giant investments in the space — though generally in late-stage companies.

Sequoia Capital, a VC giant in Silicon Valley, has invested $3.08 billion in real estate startups, including Airbnb and WeWork’s Chinese competitor UCommune, according to PitchBook. The Chinese venture firm GGV Capital and the European firm Lakestar have also invested more than $2 billion each. In addition, traditional asset management companies like T. Rowe Price and Wellington Management have also made giant investments in the space — though generally in late-stage companies.

And then there’s SoftBank.

While the company has been quietly backing real estate startups for several years — in 2014, for example, it gave the data platform Reonomy $3.7 million — its $100 billion Vision Fund has made it a kingmaker in real estate startup circles.

Within the past year alone, the fund — which launched in late 2016 — led a $865 million funding round for construction company Katerra, invested $450 million in the residential brokerage Compass and led a $120 million investment in rental and housing insurance startup Lemonade.

Clelia Peters, president of Warburg Realty and co-founder of real estate accelerator MetaProp, described SoftBank as a complete game changer.

“It cannot be overstated as a factor in terms of what’s going to transform the real estate landscape,” she said.

SoftBank’s $4.4 billion investment in WeWork last year — at a $20 billion valuation — was by far the single largest venture investment in a commercial real estate company. (It also led another $500 million round for WeWork last month.)

The valuation made some early WeWork investors a fortune and proved that backing real estate companies can lead to a big payday.

Knowing that hungry funds may be waiting in the wings has created a sense of urgency for investors to get in now.

“WeWork definitely set a precedent in the marketplace,” said Ashkan Zandieh, who runs RE:Tech, a startup research firm that tracks the venture money flooding into the industry.

The SoftBank effect goes beyond money: It’s increasing the number of tech entrepreneurs entering real estate. In New York — where not long ago real estate was considered a stodgy, impenetrable industry occupied by a tight-knit group of families — that’s leading to a noticeable demographic shift that’s making the industry look more like the tech world.

And the availability of venture capital gives real estate startups an incentive to take on the outward trappings of a tech company, so as to better land Silicon Valley cash.

On the residential front, Compass has raised nearly $800 million by casting itself as a hybrid of a tech company and a brokerage. Since launching in 2012, it’s built a Silicon Valley-like operation — with sleek offices along with titles and hires that come straight from the tech world.

Maëlle Gavet, the firm’s COO, came from travel giant Priceline Group, while Madan Nagaldinne, the company’s chief people officer, came from Facebook and Amazon. Compass also has a chief creative officer and chief growth officer. Even Leonard Steinberg recently changed his title from president to chief evangelist.

Adam Meshekow, a former executive at advertising data startup SITO Mobile, recently joined rental insurance company Leap as chief growth officer.

Meshekow said he was initially hesitant about joining a real estate insurance tech startup because he had reservations about the ability of startups to raise money, but seeing the amount of money being poured into the industry reassured him.

“The biggest change for me was seeing not just our competitors raise [money] at certain valuations, but also SoftBank’s big play into the real estate space,” he said. “The $450 million in Compass and the $150 million in Lemonade was a big deciding factor in me coming on board here.”

And there’s more cash on the way.

SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son is reportedly eyeing a second $100 billion fund along with a third and fourth.

Seeing companies like SoftBank invest billions in startups makes it more likely that others will follow suit. Sequoia, for example, is reportedly raising an $8 billion fund.

Talia Goldberg, a principal at Bessemer Venture Partners — which has invested in Blue Apron, Pinterest and others — said VC firms collectively see the potential to pour a lot of capital into real estate.

“VCs often have a little bit of a herd mentality,” she noted.

The rise of proptech funds

When Peters and Zach Aarons started pitching investors on MetaProp back in 2015, specialized funds were few and far between.

The two ping-ponged between meetings with some of the top real estate firms in the city.

But the industry players they met with were skeptical that real estate tech was the Next Big Thing.

“Generally, people listened to us, effectively patted our heads at the end and said, ‘Great to meet you. Say hi to your dad,’” said Peters, whose father, Frederick Peters, is Warburg’s CEO. (Aarons’ father is Philip Aarons, a co-founder of Millennium Partners, which owns and operates a $4 billion portfolio around the U.S.)

“There was very little belief that the vision we were describing was anywhere near coming to fruition,” Peters said.

Within 18 months, she said, those contacts were calling to ask for advice and partnerships. “This sector is moving unusually quickly,” Peters said.

The proptech VC craze was pioneered by Navitas Capital and Camber Creek, which launched their first funds in 2009 and 2011, respectively. But others have since rushed into the space, creating something of a new brain trust for the industry. (See sidebar).

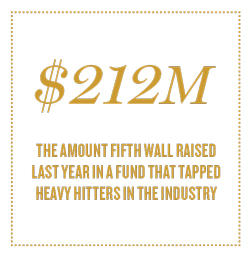

The turning point came in May 2017, when Fifth Wall, which is based in Los Angeles, raised a $212 million real estate tech investment fund from the likes of CBRE, Prologis, Hines, Lennar Corp., Host Hotels, Equity Residential and Macerich Properties.

By partnering with established real estate firms, Fifth Wall was suddenly marrying money with end users.

Brendan Wallace — a Blackstone Group alumnus who co-founded the company — touted the fund’s ability to offer “an early-stage company more distribution than any single corporate [investor] on their own.”

In January, for example, Fifth Wall led a $135 million investment in Opendoor. It then helped establish a partnership between Opendoor and Lennar, the Miami-based homebuilder with $12.6 billion in revenue last year. Under the deal, owners of Lennar homes can buy and sell their properties through Opendoor.

Fifth Wall is currently raising $400 million for its second fund.

Meanwhile, in June, MetaProp raised a $40 million fund from investors including RXR Realty, Cushman & Wakefield and CBRE to back early-stage startups.

But despite the existence of these proptech funds, several said that raising money from established Silicon Valley firms is still the ne plus ultra.

“I want someone on my board who went through 2008, who went through 2000, who supported their companies through thick and thin,” said Common’s Hargreaves. “And you’re not really able to get that with a lot of the real estate investors who have come in, because they weren’t around doing venture investing in 2008.”

For proptech funds, the preference among startups for big-name VCs can become a nagging issue, said Shaun Abrahamson, managing partner at the urban infrastructure-centric VC firm Urban Us.

If startups prefer generalist funds, proptech funds often are left to battle over smaller investments, he said.

Urban Us combats that by focusing on seed investments — the early-stage fundraising rounds where competition from big VC firms is less fierce.

Still, funds like Moderne Ventures — which has backed the chore wizard Hello Alfred and LeaseLock, which offers insurance in lieu of security deposits — bill themselves as a way into real estate investing for nonindustry players. Founder Constance Freedman said only about half of Moderne’s capital comes from real estate investors. And she looks to invest in startups that touch several industries — a move she says helps differentiate the firm in an increasingly crowded field.

Still, funds like Moderne Ventures — which has backed the chore wizard Hello Alfred and LeaseLock, which offers insurance in lieu of security deposits — bill themselves as a way into real estate investing for nonindustry players. Founder Constance Freedman said only about half of Moderne’s capital comes from real estate investors. And she looks to invest in startups that touch several industries — a move she says helps differentiate the firm in an increasingly crowded field.

Fifth Wall, MetaProp and Camber Creek, meanwhile, don’t just raise money from real estate firms — they also advise them on investments.

Rudin Management’s Michael Rudin, who oversees the family company’s VC investments, said he invested in Fifth Wall’s first fund but also used the firm as a sounding board for his own deals.

“If we saw something compelling but didn’t have time or resources to look into it, we could talk to them,” he said.

But while advising firms on how to invest is a booming business now, it may not be sustainable once these firms can act independently.

“The more successful I am, the more obsolete I get every day,” MetaProp’s Aarons said. “That makes us nervous, but what other job do I have?”

Refusing to get sidelined

After dabbling in insurance tech and investing in other real estate tech funds, the Lightstone Group launched its own fund, dubbed Torch Venture Capital, in February.

And the developer is not alone. More traditional players — from landlords to major brokerages — are investing in tech.

Sources say that’s partly because their companies can use the tech to stay ahead of the curve, but also because they’re afraid that if they don’t invest a competitor will, and they’ll get left in the dust.

Shragie Lichtenstein — whose father, David, is Lightstone’s chairman —said when he pitched the concept of launching a third-party fund to the company, he drew a graph of the public firms and REITs he believed were ignoring the tech scene.

“It was obvious to everyone in the room that none of these guys were going to make a focus on tech investment,” he said.

Lichtenstein, who is 25 and previously worked at the hedge fund Point72 Asset Management, said the goal is not to just be “waving a checkbook.”

“It’s about real, strategic value-add,” he said. “If you come to us, we’ll integrate you across our national property management platform.” While Lichtenstein declined to say how much Torch was looking to deploy, he said it will focus on startups in the late seed or Series B stage.

JLL Spark — the $100 million fund launched by JLL in June —was founded in a similar vein. A standalone division within JLL, it is headed by co-CEOs Mihir Shah and Yishai Lerner, two Silicon Valley veterans.

But most traditional real estate players in the VC space don’t have dedicated proptech teams, and they’ve limited investments to startups that can help their business.

For example, the Durst Organization, an early entrant into the space, has invested around $80 million since 2000. But unlike many VC funds that get returns of five or 10 times their initial investment, it’s seen moderate results — more on par with the S&P.

Alexander Durst, the company’s chief development officer, said he gets investment proposals daily, and he looks at all of them — whether for five seconds, five minutes or five months. But the company only invests when doing so adds value to its core business. “It’s just always been this side aspect to our business,” he said. “If we’re going to make an investment, there has to be some sort of relation to our core business so that we can gain market intelligence that we otherwise wouldn’t get.”

Being on the front lines and being able to test new concepts is a key advantage real estate companies have over other VCs.

Realogy Holdings — the residential giant that owns the Corcoran Group, Sotheby’s International, Coldwell Banker and a slew of other firms — has recently invested in tech that benefit its agents and customers.

For example, it’s working on an artificial intelligence house-hunting assistant, and last year it participated in a $20 million round for digital notary startup Notarize.

But picking winners is not easy.

Carlos Serra, a managing director at JLL, said his team was recently introduced to a startup that builds construction site canvassing robots that provide intel on things like how much drywall has been installed.

“When we got the initial pricing for this technology company, it was over $10 million just to [test] this service, so it’s very much in its infancy,” said Serra, noting that he passed on it.

But within the proptech space, investment in construction tech is rising. Last year, the sector’s funding hit $1.05 billion — a record high and 30 percent more than in 2016, according to JLL.

Still, despite that investment spike and Katerra’s splashy investment, it’s been “one of the slowest industries to adopt any level of technology,” Serra said, explaining that the vast number of stakeholders and variety of jobs makes it hard to standardize.

Companies like JLL, Rudin or Lightstone can offer themselves as investors, customers and advisors in one. While that can be a competitive advantage, it can also create problems, sources say.

Some startups, particularly data companies, balk at raising money from companies that compete with their other customers. “It can paint the picture with other clients that they will be privy to private information from their competitors,” said Reonomy co-founder Richard Sarkis.

And some observers worry that real estate companies lack the know-how to make profitable venture investments.

“There’s probably nothing more diametrically different” than investing in cash-flow-producing real estate and investing in tech startups where risks are high and returns might not been seen for years, said Fifth Wall’s Wallace.

“You need to truly understand venture investing,” he added. “That is typically the shortfall of a lot of the corporate venture funds that are out there.”

RXR’s Scott Rechler said he’s very aware of that reality, which is why he’s bringing on MetaProp as an advisor for a $50 million fund he’s launching. But, he said, investing in tech products that his company can use is a no-brainer. If RXR and other real estate players are creating demand for products, “we might as well align ourselves and profit from it,” Rechler said.

As more companies launch proptech funds, sources said, it will become even easier for startups to raise large sums of money.

And not just from Silicon Valley. The Vision Fund — which is backed by the Saudi Arabian government — could just be the beginning. Sources said sovereign wealth funds could be the next to emulate what SoftBank has done. The China Investment Corporation and the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority have already been active in financing other industries, like ridesharing, but they soon could turn toward real estate startups.

But sources said that all of this cash comes with the risk of oversaturation. “The allure of raising capital can be somewhat intoxicating,” said PeerStreet co-founder Brett Crosby. Crosby — who is pictured in a wetsuit and carrying a surfboard on the company’s website — added that startups need to be “cautious and thoughtful” about raising money.

A harsh reality about venture funding is that VC firms usually buy large equity stakes in startups and have high expectations on returns.

Although the model works well for startups like software firms, which don’t usually require a lot of capital to grow, that may become very expensive for some cash-guzzling real estate startups, said MetaProp’s Aarons. Ultimately, he argued, the industry needs cheaper alternatives to venture capital — such as debt or more patient equity.

Tellingly, WeWork, which has a capital-dependent business model, recently went to the bond market to fund its expansion, raising $702 million in an April offering.

Still, VCs said they don’t worry about increasing competition. “For the past 15 years, there was an underinvestment in real estate,” said Camber Creek co-founder Casey Berman. “For us, it’s wide open.”