TRD Special Report: You’ve heard the tale a dozen times before: From 2012 to 2014, Manhattan’s luxury condominium market was on fire. Buyers couldn’t get enough of new development product, and brokers were selling, selling, selling. Act fast, or else!

But there’s more to the real story. Though those years did see a remarkable increase in sales velocity and prices, many brokers and developers anxious to lock in buyers appear to have inflated their success — and by extension the market’s — through a variety of tactics.

Fredrik Eklund [TRDataCustom] and John Gomes, for example, rose to the top of the New York luxury-broker food chain in part by mastering the art of publicity. Their listings and deals routinely get ballyhooed on reality television, Eklund’s popular social- media accounts and all over the international press.

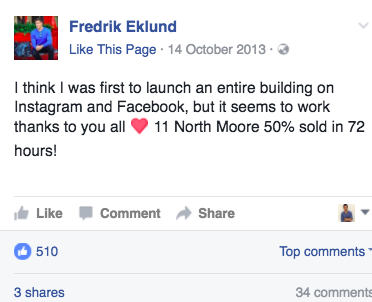

In October 2013, Eklund sent The Real Deal an email noting he had sent out contracts for eight of 16 available units at VE Equities’ 11 North Moore Street, which he claimed made the building “50% sold in 72 hours.” Shortly after, TRD published an article noting that the building is “50 percent sold out after only 72 hours on the market, according to a release from the Eklund-Gomes team,” without mentioning that this number was based on contracts sent out. Eklund then shared the article on his public Facebook feed, in a post in which he repeated the claim.

Fredrik Eklund’s October 2013 Facebook post in which he claims 11 North Moore hit the 50% sold mark (Credit: Facebook)

In fact, public records show that by the end of October of that year, just four units had gone into contract. The eighth contract at the building wasn’t signed until June 2014. The problem here is that just because contracts are sent out doesn’t mean they will be signed. “’Contract out’ means nothing,” Olshan Realty’s Donna Olshan said. In this case, the onus falls at least as heavily on TRD as it does on Eklund for pretending otherwise.

When asked to comment for this story, Eklund denied misrepresenting any information. He also threatened to sue TRD.

The 11 North Moore case is just one example of what has become a deep-rooted problem in New York’s luxury residential real estate market. Sales updates, strategically dished out via interviews and press releases, are a crucial marketing tool. But developers and their brokers, operating in a market lacking clear rules and oversight, often provide murky and misleading numbers, according to brokers, attorneys, and market observers.

“There’s an innate desire amongst some of us to distort information,” said Leonard Steinberg, president of Compass. “I’ve heard people say ‘it’s completely sold out’ and the next week, four units were available. It’s not a healthy practice.”

Deceptive numbers can impact buyers’ decisions by creating an embellished picture of a project’s success. Competing developments that don’t engage in the practice could see their projects fall behind as buyers flock to the hottest new building in town. And as the city’s luxury market slows down, the problem is bound to get worse.

“There’s so much pressure on these guys to sell,” Olshan said. “They’re just trying to invent ways to show their property is more successful than another one.”

Sleight of mouth

Stella Tower at 425 West 50th Street, Chelsea Green at 151 West 21st Street and the Schumacher at 36 Bleecker Street

Developers rarely (if ever) get called out on the practice because sales numbers on new projects are hard to verify. Unlike closings, which appear in the public database ACRIS within a week or two of the event, information on signed contracts isn’t quickly available.

But once a sale closes (often several months or years after the contract was signed) the contract date enters public records as part of the deed document. Examining the deeds allowed TRD to track contract signings over time and compare them with public sales updates.

We found no instances of outright lying. Far more often, developers and brokers round up numbers or use figures selectively to make their projects look hotter than they actually are.

Consider Chelsea Green, a 51-unit condo at 151 West 21st Street. Even in 2012, a robust year for the luxury market, the project by Alfa Development seemed to stand out. Sales kicked off in May 2012, and by mid-August, the New York Daily News had dubbed the project “New York real estate’s biggest summer success story,” referencing its sales prowess. On Oct. 17, 2012, Alfa’s Mike Namer told the New York Times the project was “90 percent sold.”

But public records indicate otherwise. Just 34 units, or 67 percent of the project, were in contract by Oct. 17, 2012, ACRIS data show. The building didn’t officially hit the 90 percent-sold mark until December 2014. According to a source, Namer had decided to buy eight units in the building for himself or family members at a later date and treated these units as sold. Even if you include them in the tally, the building was 82 percent sold by the time he spoke to the Times.

“Alfa Development communicates with full transparency and accuracy about the sales performance of its buildings,” a spokesperson for the firm told TRD.

On June 28, 2013, the New York Daily News gave the Schumacher, a 20-unit boutique condo at 36 Bleecker Street developed by Stillman Development and marketed by Eklund-Gomes, the full-page treatment. The story, which ran with a gushing headline, “Gallery-like units at The Schumacher fit for a fine art show,” said that just two weeks after hitting the market, half the project’s 20 units were already in contract. And Gomes made it sound like he could have sold the rest as well if he had really tried.

“We don’t want to sell too fast because we might sell ourselves short,” he said.

In fact, Eklund-Gomes hadn’t sold a single unit at the time of the article’s publication, public records show. Roy Stillman, president at Stillman Development, told TRD the building’s condo offering plan hadn’t been approved at the time. No actual sales contracts had been signed; instead, potential buyers had merely signed nonbinding reservation agreements with the help of a special permit from the New York attorney general — not actual sales contracts. According to Stillman, some of those buyers later changed their minds and got their deposits back.

It wasn’t clear whether Gomes or Stillman had relayed that crucial bit of information to the Daily News, and whether the latter had simply neglected to include it in the article. The article’s author, who no longer works for the publication, did not respond to a request for comment. Either way, the piece was never corrected. On July 19, an article in the Wall Street Journal repeated the (still inaccurate) claim that half the building’s units were in contract.

Asked to comment via email, Gomes denied that no units had sold by the time the Daily News article was published and accused this reporter of “dragging our names in the mud for your own benefit.”

Gray areas

Another common trick is to pick an artificially late official sales launch date to make sales velocity appear faster than it is. On June 5, 2014, for example, sources involved in the Stella Tower project told TRD that 60 percent of condos at the property sold “one month after hitting the market.” But public records show that the first contracts were signed on April 1, meaning they were likely up for sale as early as at least March — not May, as suggested. A spokesperson for JDS Development Group, which developed the project along with Property Markets Group, declined to comment.

And even if a public sales update is technically accurate, it can still be a misleading indicator of financial success. “The larger the unit, the slower the absorption rate,” said Jonathan Miller, CEO of appraisal firm Miller Samuel. “Typically, the initial units tend to be small to midsized.” Because smaller, cheaper units tend to sell faster, even if 50 percent of units are sold their combined sales revenue may be far less than 50 percent of the total projected sellout. At Stella Tower, for example, 53 percent of units have a contract date prior to June 5, 2014 – but their combined sales price only amounted to 39 percent of its projected sellout.

And developers don’t just enhance sales numbers. They sometimes use tricks to exaggerate sales prices.

Petro Zinkovetsky, an attorney who specializes in working with condo buyers, said that about 10 percent to 15 percent of deals he has worked on include a so-called price-concession. The publicly recorded condo sales price on ACRIS may be $10 million, for example, but the parties attach a rider document to the deed detailing a $1 million discount. In this scenario, the buyer only pays $9 million, but anyone who searches public records thinks she paid $10 million because the concession rider doesn’t hit ACRIS. Potential buyers may think that other units in the building sold for more than they actually did, which might persuade them to cough up more money themselves.

All sources interviewed by TRD insisted that false or misleading sales updates are not the norm. Jacky Teplitzky, a broker at Douglas Elliman, pointed out that condo sales in New York City are far more tightly regulated that than in other states, such as Florida, where practices like this are far more widespread.

And sometimes, even the most outlandish-sounding numbers turn out to be accurate. In April 2013, for example, Witkoff’s condo development 150 Charles Street reported that almost 80 percent of its 91 units had sold a mere two months after sales launched. A review of public records shows that this was indeed the case. Still, brokers and attorneys say fuzzy math is far too common.

The world Trump made

The luxury condo market’s loose relationship with facts owes much to its pioneer: Donald Trump. New York has historically been a renters’ town, and large-scale condo construction didn’t take off until the early ’80s. Most new for-sale apartments at the time were moderately priced. It was Trump who played an outsized role in the rise of the Manhattan luxury condo. In 1980, he filed plans for his first major condo tower, Trump Tower at 725 Fifth Avenue, and followed it up with six more condo projects totaling 1,565 apartments, according to a recent TRD analysis.

He also ushered in an era of trumped-up sales numbers, a practice he described in his best-selling 1987 “The Art of the Deal,” as “truthful hyperbole.”

“I play to people’s fantasies,” Trump wrote. “People want to believe that something is the biggest and the greatest and the most spectacular. I call it truthful hyperbole. It’s an innocent form of exaggeration — and it’s a very effective form of promotion.”

That ethos seeped into the market, said one industry source speaking on condition of anonymity. “This is Trump and a version of him,” the source said. “It’s the same group, the same collective consciousness of going out there and saying whatever.”

So, what’s the big deal if developers and brokers want to exaggerate a little?

Because sales velocity is an indicator of a project’s desirability and value, giving false or misleading sales updates can trick people into buying condos they otherwise wouldn’t. It could also hurt prospects at rival projects, which may lose buyers to the development talking the biggest game. And though developers generally do far more due diligence than buyers, an unsavvy developer may see a nearby project’s inflated success as impetus to move ahead with his or her own project, even if the time is not quite right for it.

Official sales data are often incomplete and typically come with a time lag, so sales announcements are widely treated as an indicator of the strength of a project, and of the condo market. A Daily News reader who sees that pads at the Schumacher are flying off the shelves may conclude that Downtown luxury condos are a hot commodity and may decide to buy one nearby. In this sense, fudging sales updates can distort a condo market that has grown enormous — the combined value of all new condo offering plans approved in New York City in 2015 alone was $27.8 billion, larger than the individual GDPs of 92 countries, according to World Bank figures.

“There’s comfort in velocity,” said Jason Haber, a broker at Warburg Realty. “There’s comfort in knowing other people have bought there.

Misleading sales numbers may also impact a buyer’s ability to get cheap financing. The Federal Housing Agency generally requires that 35 percent of units in a new development condo be sold before buyers can get Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac loan. (The threshold was lowered from 50 percent in July.) Buyers who think a building is over 35 percent sold when it really isn’t may be in for a rude awakening when trying to get an FHA-backed loan.

Developers who publish false numbers also face legal risks. Giving false sales updates can be a “tremendous liability” for developers, said Pierre Debbas, a partner at law firm Romer Debbas. Because sales velocity in a building is “material information” buyers consider, they can later sue if it turns out they were tricked.

“When the recession took place everyone wanted out of their sponsor contracts, and a lot of people sued over false representation,” he said.

Trump was someone who learned that a little hyperbole isn’t always harmless. In November 2011, buyers at the Bayrock Group and Trump Organization’s Trump Soho sued the developers, claiming they were tricked into buying apartments through false sales updates. In June 2008, for example, Ivanka Trump told Reuters that 60 percent of units had been sold. In fact, only 15 to 30 percent of units had been sold by early 2009, according to a New York Times report. The developers agreed to settle and refund 90 percent of buyers their deposits.

That kind of blatant lying has become rare amid growing awareness of the consequences, said Adam Leitman Bailey, the attorney who filed the Trump Soho suit.

“They’re not lying,” Bailey said, “but they’re playing with the truth.”

Debbas said that developers are now far more reluctant to disclose sales information to buyers’ attorneys, for fear of legal liability if they turn out to be wrong. He predicted that a potential downturn in the luxury condo market could lead to more lawsuits in the mold of Trump Soho, as buyers look to get out of contracts for apartments whose value is falling. As these suits produce revelations of inflated sales numbers, they could in turn erode buyer confidence in the health of the condo market as a whole, and push the market even further into a funk.

“When the market is good people aren’t as concerned,” Debbas said. “It’s when the market goes south that people are saying: ‘Now I’m really worried.’”

[vision_pullquote style=”3″ align=”right”] “This is Trump and a version of him. It’s the same group, the same collective consciousness of going out there and saying whatever.” – source [/vision_pullquote]Doug Heller, an attorney at Herrick Feinstein, said that even misleading updates — such as claiming a building is 50 percent sold when contracts have been sent out for 50 percent of units, or treating non-binding reservation agreements as sales — can be a “misrepresentation.”

Developers who misrepresent facts run the risk of being banned from selling condos, Heller said, while brokers could lose their license.

It is telling that Vornado Realty Trust, a public company that faces stricter regulatory scrutiny than private developers, has refused to give sales updates on its luxury condo development at 220 Central Park South for five straight quarterly earnings calls.

Vornado CEO Steve Roth said on Aug. 2 that the development “is a very public project, so everything that I say gets into the newspapersand whatever, so we don’t have a lot to say about [it].”

But despite the legal dangers, false or misleading sales updates are still common, as some of the examples above show. So why take the risk?

One reason may be because people can get away with it. Heller said the AG simply lacks the staff and resources to go after any but the most extreme cases.

“People who lie are misleading the potential purchaser and commit fraud,” he said. “If the AG had the energy I’m sure they would be throwing the book at all of them.” The AG’s office declined to comment for this story.

Another explanation is the tremendous pressure developers put on new development marketing firms, one source said. As sales slow across the luxury market, sales brokers are replaced with increasing frequency, and to keep their assignments use any and all tricks to sell apartments.

Sometimes, developers will pressure brokers to publicize rosy sales updates to exempt themselves from any liability, the source said. And even when they don’t, they may still tacitly endorse the practice. “I honestly think [brokers] do know it’s illegal and wrong, and the sponsor knows what’s happening and he turns his back because it’s benefiting him,” a senior brokerage executive said. The problem, according to the executive, is a lack of oversight and enforcement.

[vision_pullquote style=”3″ align=””] “If the AG had the energy I’m sure they would be throwing the book at all of them.” – Doug Heller [/vision_pullquote]Adding more oversight shouldn’t be too hard. The AG’s office already requires developers to file condo offering plans, and all closed sales are recorded publicly. It could also compel developers to file monthly or quarterly sales updates as well. These numbers “should have to be disclosed so that buyers and their representatives know what they’re buying into,” the brokerage executive said. “We have the wherewithal and it’s an easy fix.”

Kyna Doles contributed reporting.