Stephen Siegel, the chairman of CBRE’s global brokerage division, is a notoriously lousy golfer. On a good day, he can shoot below 100 — maybe.

Nevertheless, last October, Siegel gamely showed up at Reynolds Plantation, a lakeside resort in Greensboro, Georgia, for Brookfield Property Partners’ annual golf outing. All told, 60 commercial real estate brokers made the trip.

The skies were ominous. After a downpour, club officials instructed golfers not to drive their carts for fear of muddying the course. But Siegel, a wisecracking Bronx native, drove out anyway. After all was said and done, he left a black trail of six-inch-wide tire tracks across the once well-manicured green fairway.

When approached by stern-faced club officials, Siegel did what came natural to him — the husky-voiced salesman talked his way out of it.

“My experience negotiating comes in handy outside the boardroom, too,” he said with a chuckle from behind the desk of his 21st-floor office at CBRE’s Manhattan headquarters.

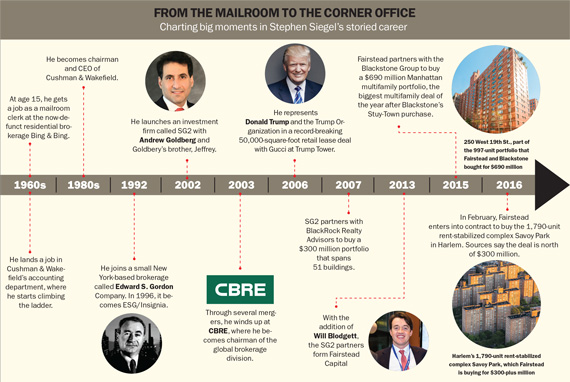

In New York City, Siegel, 71, has been described as the godfather of commercial real estate, lauded by the industry as a larger-than-life figure with a sales pitch to match and a storybook career that clearly outshines his golf game. He has gone from being a top broker to a CEO and back again.

All told, he has worked on hundreds of commercial real estate deals. His clients have included a mix of high-profile landlords and tenants, including Silverstein Properties, the Trump Organization, SJP Properties, Hudson’s Bay Company, L’Oreal and JPMorgan Chase. His brokerage business essentially speaks for itself.

Given his success in that world, it may come as a surprise to some in the industry that over the years Siegel has quietly pursued another career — that of an investor.

In 2002, he launched the firm SG2 Properties with partners. And he has personally invested in a number of New York City restaurants, including Sarabeth’s, the Knickerbocker Bar & Grill and P.J. Clarke’s. Plus, he owns a stake in a minor league baseball team — the Tri-City ValleyCats, which is based in upstate New York and part of the Houston Astros franchise.

But lately, Siegel’s “side” career has become increasingly prominent and virtually impossible to miss.

He is currently one of four partners running Fairstead Capital, a real estate investment and asset management firm that specializes in the multifamily market. The firm has accumulated about 5,000 units valued at more than $2 billion.

In September, Fairstead made its splashiest deal to date when it partnered with private equity giant Blackstone Group to buy a $690 million Manhattan multifamily portfolio.

The 24-building, 997-unit package — spread across Chelsea and the Upper East Side and owned by the Caiola family — was the second-largest multifamily deal of 2015 after Blackstone’s purchase of Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village.

The transaction elevated Siegel into a new league in the investment sales world.

“Stephen is very trusted by institutional players and local major operators in New York,” said Paul Massey, president of New York investment sales at Cushman & Wakefield. “He is on every investment sales broker’s radar.”

Indeed, that mega purchase would not have been possible if Siegel didn’t have an extensive Rolodex to tap into for capital. He personally brought the deal to Jonathan Gray, Blackstone’s global head of real estate. The two have known each other for about 10 years, and the relationship helped convince Blackstone to sign on.

“[He’s] someone of integrity, whom you can trust on a handshake,” Gray said of Siegel.

The moonlighting investor

Siegel has been grooming his investment business for more than a decade.

During the late 1990s, Andrew Goldberg, a top CBRE retail broker, and his brother Jeffrey were investing in multifamily buildings in Harlem when the market was hot. For Siegel, this was a chance to get in the investment game with two friends. “It was something I wanted to do for a long time,” he said. In 2002, the three founded SG2. (The “S” stood for Siegel and “G2,” the two Goldberg brothers.)

The following year, the firm teamed up with a family office, which served as a silent partner to provide equity on deals. Siegel declined to identify the family firm and the Goldbergs declined to comment.

In 2007, SG2 bought a $300 million, 3,600-unit portfolio in the Bronx with BlackRock Realty Advisors. Three years later, it bought out BlackRock’s interest and brought on E&M Associates, now known as Galil Management, as a partner.  Over the next five years, SG2 and E&M sold off the entire portfolio to several investors for a combined $340 million. In 2013, SG2’s partners changed the company name and took steps to restructure by teaming up with a full-time property management firm and opening an office in the 60-story Carnegie Hall Tower in Midtown West.

Over the next five years, SG2 and E&M sold off the entire portfolio to several investors for a combined $340 million. In 2013, SG2’s partners changed the company name and took steps to restructure by teaming up with a full-time property management firm and opening an office in the 60-story Carnegie Hall Tower in Midtown West.

“We wanted something a little more formalized and a little more focused because we had access to a lot of capital,” Siegel explained.

The 10-person firm is headed by Siegel, the Goldbergs — Jeffrey runs daily operations; Andrew, like Siegel, works at CBRE — and Will Blodgett, a former SG2 employee who most recently worked at Related Companies.

Sources credit the 33-year-old Blodgett with persuading the heirs of the late developer Benny Caiola to sell their massive portfolio. The family was reluctant to do so after Thor Equities backed out of a soft contract to pay $800 million in early 2015.

Between Blodgett’s persuasion and Siegel’s capital connections the deal came together. And it was something of a game-changing moment for Fairstead.

“It was the combination of the visibility of the portfolio and the visibility of the institutional partner,” said Jonathan Mechanic, chairman of Fried Frank’s real estate department, who represented Fairstead in its joint venture with Blackstone. “Blackstone doesn’t partner with just anybody. Their partnership says that Fairstead has a keen sense of value and market knowledge. If a prospective partner of Blackstone’s doesn’t have that, there are a 1,000 other people willing to partner with them.”

And Fairstead did not stop with that deal.

Late last month, it struck another big deal, entering into contract to buy the 1,790-unit rent-stabilized complex Savoy Park in Harlem from an investor group led by L+M Development Partners and Savanna. Sources said the deal is valued at north of $300 million.

Savoy Park

An offering memo issued by the sellers in November indicates that 800 of the units at the entirely rent-stabilized complex are ripe for renovation and price increases.

But a spokesperson for Savoy Park said at the time that any “value-enhancement plan” would take “decades to achieve.” And a Fairstead representative said last month that the company is “committed to preserving affordable housing at Savoy Park.”

Generally, Fairstead tries to keep at least 20 percent of its holdings as affordable housing and is relatively conservative in its investment strategy. The vacancy rate in its portfolio is about 1 percent and it typically borrows a conservative 50 percent to 60 percent. (The Caiola deal, which was financed with a $592 million loan, or 86 percent debt, was something of an anomaly.)

Siegel said he is not looking for risky bets — or to invest for the sake of investing. “Understand what you’re trying to buy and don’t just buy because it’s available,” he said.

And he said his top priority is still very much brokerage. He’s typically at CBRE’s office every day during business hours.

His title as CBRE’s chairman of global brokerage is a bit misleading given that he doesn’t play a managerial role. He works exclusively as a broker on office leasing and office building sales.

According to Siegel, he is hustling just like every other broker. “Colleagues here are going after the same clients I am,” Siegel said. “I compete with my colleagues and they bring me into transactions on occasion.”

Fairstead, he said, has been an after-hours pursuit. He said he takes calls for the business mostly at night and meets with his three partners around 7 a.m. during the week and on the weekend.

Still, he joked, “I give each of them 24 hours every day.”

Climbing the ladder

Siegel started out as a mailroom clerk at age 15 at the now-extinct residential brokerage Bing & Bing.

Two years later, he landed a job in Cushman & Wakefield’s accounting department. There, he spent the next two decades climbing the corporate ladder, eventually grabbing the brass ring of chairman and CEO.

He left Cushman in the late 1980s and went to the Chubb Corporation for a few years to try his hand at investing, but left when the market crashed. He then returned to brokerage as president of the now-extinct Edward S. Gordon Company, which after several mergers ultimately folded into CBRE.

In the commercial brokerage industry, he is known for being able to defuse tension during negotiations with his comedic quips.

“He’s as quick with a line as anyone I’ve been around who is not paid to be funny,” said Mitch Rudin, the CEO of Mack-Cali Realty Corporation.

Friends have likened him to Don Rickles, Jackie Mason and Johnny Carson, noting that he blends Borscht Belt humor with a dry wit and debonair delivery. At a charity event in 2009 he performed standup at the famed Caroline’s comedy club on Broadway and he’s also a member of the comedy institution the Friars Club, which has a business associate category for membership.

His outgoing personality has helped him seal some of the biggest deals of his career.

In 2006, he represented the Trump Organization in a retail deal with Gucci at Trump Tower, and Silverstein in a 20-year lease with Moody’s at 7 World Trade Center. (He didn’t keep in touch with Trump, but in typical Siegel fashion he quipped that he very well could be “secretary of state” if Trump makes it to the White House.)

More recently, he helped snag large office spreads for luxury brands at the Hudson Yards megaproject. In 2013, he represented L’Oreal in a 402,000-square-foot lease at 55 Hudson Yards and was a member of the team that represented Coach in its 740,000-square-foot deal at 10 Hudson Yards.

Siegel noted the L’Oreal lease was particularly taxing, with negotiations often dragging into the early morning hours.

He is currently representing the New York State Department of Health and the Public Service Commission as they negotiate a 250,000-square-foot renewal at the U.S. Postal Services’ 90 Church Street.

Bruce Mosler, who sits in a parallel role at Cushman & Wakefield as chairman of global brokerage, said of Siegel, “He doesn’t look to score points. He just wants to get the job done.”

Bruce Mosler

He then added: “And there is nobody who does it better.”

But Siegel’s dual commitment to brokering office lease deals and making large building acquisitions, both concentrated in Manhattan, does raise the question of a conflict of interest.

Siegel said his investment business does not intersect with the brokerage’s New York investment sales team, led by Darcy Stacom and William Shanahan. And according to CBRE’s website, employees can make “certain types of commercial real estate investments,” provided they are disclosed.

“Such requests are approved only after a review of potential conflicts and if the outside activity does not present a substantial risk of confusing clients or others as to the capacity in which the employee is acting,” the policy states.

When asked about it, Siegel said, “The asset class we focus on [at Fairstead] is multifamily, so I’m not really competing. If a client of CBRE on a rare occasion is looking at a portfolio we’re looking at, we’re not going to compete with that client.

There are firms in the city that represent office tenants and own office buildings. We don’t.”

Getting personal

Siegel is ever-present on the New York City social circuit — from parties to panels to steakhouses to niche social clubs.

Boston Properties’ John Powers said he once met Siegel in Greenwich Village for dinner at one of his go-to spots: Tiro a Segno. Nicknamed “the Italian rifle club,” it’s the oldest Italian-American club in the U.S. and has a basement shooting range.

Powers recalled, “I said to him, ‘Steve, you’re not Italian — you’re Jewish — and you don’t own a gun.’ He said, ‘Yeah, but the food is great and the people are wonderful.’”

It’s that level of social engagement that’s helped him in his business and personal life, sources said.

In addition to feeding his career with new clients and connections, it also created a support system when his wife, Wendy — whom he lives with in a townhouse on East 65th Street and Park Avenue — was diagnosed with leukemia back in 2012. For more than a year, the couple lived in Boston while she underwent treatment, and in 2013, she received a bone marrow transplant.

Siegel is known as a committed family man all around. The couple has four children, two of whom Siegel has attempted to bring into the commercial brokerage fold.

Their 26-year-old daughter, Cassandra, recently completed a nearly two-year CBRE program, but left to attend law school. Jared, 29, who has turned down offers to work for his dad at CBRE, is a principal at Soho-based Squire Investments.

Still, Siegel does not seem ready to pass the reins to the next generation quite yet.

He says he still has more to do himself. “Is there anything I would like to do?” Siegel said. “Yeah, I’d like to win 10 more ‘Deal of the Year’ awards and some more ‘Ingenious Deal of the Years.’

“I’d like to make two or three more very significant additions to Manhattan’s skyline. There’s a lot of things I’d like to do. That’s what motivates me every single day.”