Residential condo development is the riskiest sector within the risky business of real estate. Evidence for that is found in both the outsized returns builders can achieve with a success and the ruin they can bring upon themselves and their partners if they fail.

It’s why in Manhattan’s ultra-competitive real estate world it’s the players who develop flashy condo towers who achieve celebrity status. In the last 12 months alone, roughly $4.7 billion in new condos sold in Manhattan, city property records show.

But while the industry’s peanut gallery speculates on winners and losers in today’s market, The Real Deal went back over 50 years — to when condos first began selling —to see how today’s top developers (from Extell Development [TRDataCustom] to the Related Companies to Harry Macklowe) fit into the historical landscape. We also wanted to see where some of New York’s most famous developers, most notably Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, landed in the mix.

So in a first-ever analysis, TRD sifted through all of the condo buildings (of 50 units or more) brought to market in Manhattan since 1965 — when Lyndon B. Johnson was in the White House and Robert Wagner was in City Hall. There were more than 500 projects in total, encompassing more than 80,000 units.

We then determined the developer on each project and ranked them by how many residential condo units they built or converted — and how much those units were valued at. (TRD identified the developer as the public face of the project or the firm that filed the public documents.)

Some of the developers actively building in New York now didn’t make the cut on the ranking, but if they complete their current batch of projects they will no doubt join the giants of the past soon.

Overall, we found that with the exception of the Zeckendorf family, Extell’s Gary Barnett and Related, most of today’s developers (even the high-profile ones) have built far fewer condos than their counterparts of yesteryear. That may be because the possibility for failure is so great.

“ It’s a business fraught with risk,” said Barnett. (Even Barnett, widely considered the most successful condo developer in the current market, has struggled to get a loan for a large project he’s planning on the Lower East Side.)

It’s a business fraught with risk,” said Barnett. (Even Barnett, widely considered the most successful condo developer in the current market, has struggled to get a loan for a large project he’s planning on the Lower East Side.)

Below is a look at the developers who defined their times and how much they contributed to the residential condo world that’s become such a force in New York today.

The prolific players

It’s hard to compare condo developers to each other without understanding how the development landscape in New York completely transformed in the 1980s.

The explosive condo development of that decade left an oversupply of units in its wake.

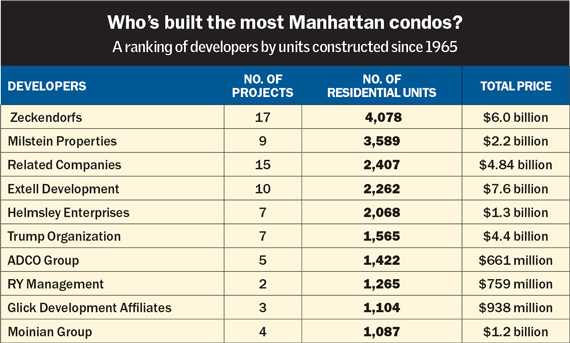

The Zeckendorf family — long led by William Zeckendorf Jr., who died in 2014 — was the most active developer during that boom. That activity helped buoy the Zeckendorfs to the No. 1 spot on TRD’s ranking in terms of condos brought to market.

Over the course of nearly 35 years, Zeckendorf and his sons, William Lie and Arthur, built nearly 4,100 units.

In addition to the Zeckendorfs, the other developers in the top five (by number of condo units filed with the state) are all familiar names today: Milstein Properties, Related, Extell and Harry Helmsley’s Helmsley Enterprises. The Trump Organization, meanwhile, took the No. 6 spot. (Milstein and Helmsley wound up high on the list because of their work in the 1980s, while Trump’s development in the 1980s and 1990s secured him a spot on the ranking).

But perhaps the Zeckendorfs’ trajectory tells the boom-and-bust story of the 1980s and 1990s best.

In 1982, Zeckendorf Jr. — whose father William Zeckendorf Sr. was a larger-than-life figure in the real estate business — filed plans for his first large condo project, the Columbia, at 275 West 96th Street. That 301-unit project was followed quickly by an astonishing burst of activity. Zeckendorf filed plans for 14 more projects over the next 10 years, with more than 3,600 units. Nearly all those projects were new construction.

Source: TRD analysis of NYS Attorney General and NYC Dept. of Finance filings, news articles and sources. Numbers include condo plans that were declared effective by the AG since 1965 and through February 2016. Only Manhattan projects of 50 units or more were included. TRD used the sellout prices that were filed with the AG’s office for final price tallies and gave credit only to the developers who appeared in public records or were the primary public face of the project.

But the family ultimately lost hundreds of units to its lenders — a move that also marked the end of its condo development run during that period.

The last project it filed before the economy began tanking and the recession hit in the 1990s was a 239-unit condo at 170 East 87th Street known as the Gotham. But with weak sales, the bank took control of the project and the party came to an end.

“I was there,” William Lie told TRD earlier this year, referring to the recession. “It was horrible. It’s not fun to owe banks money. I never want to owe banks money.”

But that financial bind didn’t scare the Zeckendorfs off. In 1998, after Bill retired, William Lie and Arthur launched their own firm, Zeckendorf Development, with 515 Park Avenue. (And in 1999, they also repurchased all of the unsold units at the Gotham and began marketing that building again.)

While the Zeckendorfs have built far fewer units in the last decade than in the past, they have pushed the price envelope at many of their more recent projects, including the game-changing condo 15 Central Park West, 18 Gramercy Park and their new luxury tower at 520 Park Avenue.

Milstein Properties, meanwhile, made the cut on TRD’s list with 3,589 units, thanks to the condos it built in the 1980s in Battery Park City — a neighborhood it dominated on the development front. But the company put the brakes on its condo development for years after that, until it began constructing two large projects: 30 Lincoln Plaza near Lincoln Center in 2006 and Liberty House in Battery Park City in 2008.

Numbers 3 and 4 on TRD’s ranking — Related and Extell — are among the biggest names in real estate today.

Related, with 2,407 units, filed its first condo plans in 1985 — for two towers in Battery Park City, the 121-unit Soundings and the 153-unit Battery Pointe — and hasn’t stopped since.

Gary Barnett and One57

The firm’s breakout decade was the 2000s, when it built the massive mixed-use Time Warner Center in Columbus Circle, which included more than 400 condos. The firm has built a slew of high-profile projects since and is currently in the midst of building the biggest mixed-used project in the country at Hudson Yards on Manhattan’s Far West Side. That project will have office towers, hotels and rentals in addition to three condo towers.

Barnett, meanwhile, began building large condos in 2004, with the Orion, a 551-unit tower at 350 West 42nd Street. He then began a run similar to Zeckendorf’s, launching eight projects with more than 1,800 units before the economy collapsed in 2008 and development halted. Overall, he has completed 10 large projects with 2,262 units — though he has many more units in the pipeline.

He was also the first major developer to begin building as the economy recovered from the 2008 crash, with his 1,005-foot-tall condo-and-hotel tower, One57. The building has a nearly $3 billion sellout price filed with the state attorney general and sale prices north of $6,000 per square foot. It also launched the Billionaires’ Row frenzy on West 57th Street.

Next up on the ranking is Helmsley, who may be better known as one of the city’s legendary commercial owners. But he also was a major residential landlord, with plans filed for 2,068 units at seven projects — all conversions.

And Helmsley, who died in 1997, was actually a pioneer in the condo world. His first project was the 1973 conversion of a 183-unit rental building on West 55th Street called the Gallery House. It was only the third condo building of greater than 50 units to debut in the city.

His largest project was the conversion of a batch of post-war high-rises that were part of the Upper West Side’s Park West Village complex. He acquired the buildings in 1972, and filed to convert four of them to condos in the 1980s.

The conversions were controversial and challenged by both the state and tenant groups because the apartments were developed in the 1950s as part of a federal urban renewal project. But in 1985, a judge cleared the way for the conversions, ruling that Helmsley could proceed because no federal money was used to develop the buildings.

Finally, Trump built 1,565 condos overall. (His name appears on four giant projects along the West Side Highway that TRD did not give him credit for because he was not the developer, according to public records and sources.) He’s also now all but out of the condo game and has instead focused on golf courses and the licensing arm of his business.

Trump’s first project, Trump Tower at 725 Fifth Avenue, was filed in 1980 and came on the heels of Aristotle Onassis and Arthur Cohen’s 1975 project Olympic Towers at 645 Fifth Avenue. The two projects, which were just five blocks apart, helped firmly establish Midtown as a market for luxury condos.

From there, Trump built six more projects, although at one of them — Trump International Hotel and Tower, at 1 Central Park West — he reportedly did not have any equity invested. The last condo project Trump developed, according to TRD’s analysis, was 502 Park Avenue, a 122-unit condo conversion. Plans for the project were filed in 2002, and the units hit the market the following year.

The moneymen

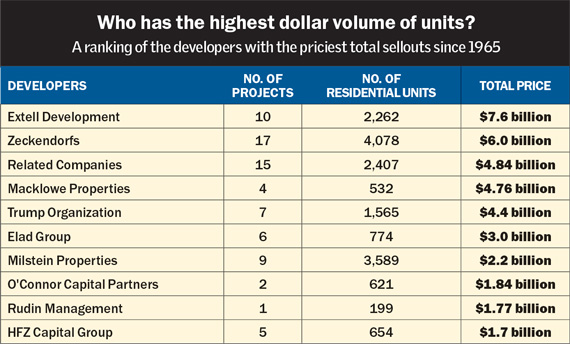

While measuring developers by number of units is one key metric, perhaps even more telling is how much they are looking to sell those units for.

During the condo explosion of the 1980s, many developers (with the exception of Trump and a few others) were building run-of-the-mill, moderately priced condos. Today, the paradigm has shifted decidedly to luxury.

Source: TRD analysis of NYS Attorney General and NYC Dept. of Finance filings, news articles and sources. Numbers include condo plans that were declared effective by the AG since 1965 and through February 2016. Only Manhattan projects of 50 units or more were included. TRD used the sellout prices that were filed with the AG’s office for final price tallies and gave credit only to the developers who appeared in public records or were the primary public face of the project.

“The apartments were really stripped down [back then], they were nothing fancy,” Daniel Brodsky, senior partner at the Brodsky Organization, told TRD, recalling the Walton Hotel on West 70th Street, which his company converted to condos in the early 1980s. Prices there, he said, averaged $150 per square foot. By comparison, condo prices at his latest project on East 79th are about $3,000. And while astronomical for most New Yorkers, $3,000 a foot is moderate for the luxury market, where the priciest units have sold for upwards of $10,000 per square foot.

Two key factors played into the exponential growth of New York real estate prices: The overall national jump in prices and a new focus on building luxury real estate on a level never seen before.

As a result, when TRD flipped the ranking and tallied the results by the sellout price filed with the AG’s office, the findings looked different even when adjusted for inflation.

Extell topped the ranking by value. The company’s condos had a cumulative sellout price of more than $7.6 billion.

The other developers at the top of the dollar-volume ranking are Zeckendorf (with $6 billion); Related (with $4.84 billion), Macklowe Properties (with $4.76 billion) and Trump (with $4.4 billion). While Macklowe has few units, he was buoyed to the upper echelon of the list by his über-luxury condo tower 432 Park Avenue.

For his part, Trump’s projects in the 1980s and 1990s were some of the priciest of their time. When the presidential candidate filed plans for the mixed-used Trump Tower — a combo retail, office and condo building — glass projects were still a novelty.

Total sellout prices at his projects (adjusted for inflation) ranged from $70 million at the 81-unit Trump Parc East at 100 Central Park South to $981 million at Trump World Tower at 845 United Nations Plaza. But not all of his units sold out quickly. He still owns large blocks of units in several of his buildings.

Nonetheless, he was among the first to recognize that foreign buyers had an appetite for New York City real estate but couldn’t breach the clubby and biased views of co-op boards.

Harry Macklowe and 432 Park Ave

“There were fewer restrictions on sales and leasing, it was easier to finance,” said Alvin Schein, an attorney who focuses on condo and co-op plans, explaining why overseas buyers favored condos. Schein said it was also easier for foreign buyers to use LLCs or other entities in their purchases that would shield their identities when buying condos.

The irony is hard to miss: In today’s presidential campaign Trump has pushed anti-immigration policies, including a wall along the Mexican border and a ban on Muslims entering the country, a position he seemed to waffle on last month.

Risky business

The condo development business, especially in New York City, is not for the faint of heart. The list of developers who’ve had projects go belly up — or run into even bigger financial trouble — speaks to that loud and clear.

“The streets are lined with the bodies of failed developers,” said Robert Shapiro, a broker at City Center Real Estate, who’s been in the business since the 1980s.

Despite the perception that condo development is lucrative, making money by building for-sale apartments in New York is actually incredibly difficult.

Francis Greenburger — who has developed condos in New York since the 1980s and developed co-ops in the 1970s — said it’s all about timing.

“If you hit the market at the right time, you are OK,” he said. “If you hit at the wrong time, you are dead.”

Greenburger said typical condo developments look to give equity investors a “two-times” return. That means that if those investors put in $1 million of their own money, they would recoup that and get an additional $1 million. While that may sound like a good deal, big projects can take four or more years, making the actual annual return more like 20 or 25 percent — and that’s assuming absolutely nothing goes wrong.

But smooth sailing is often the exception to the rule.

The city is littered with examples of condo projects gone awry, from Ira Shapiro’s troubles with One Madison Park, which ended in bankruptcy, to Ian Bruce Eichner’s CitySpire, which was lost to lenders (and later completed by the Zeckendorfs).

Brodsky told TRD that his firm did well at 135 East 79th Street, which it filed plans for in 2012, but that it’s had other projects that have barely broken even. For example, back in the 1980s, it struggled with 29 King Street in Soho. Even after holding some units and renting them out for a few years, “we did not do well with it,” he said.

“We did not make pro forma,” he noted.

The first oddity

The first condo building to open in New York was the 300-unit St. Tropez, which was also the first condo building to fail.

Manhattan buyers, who were long accustomed to co-ops, viewed the new structure at 340 East 64th Street as an oddity. It was 1965, and lending was tight so it was hard for many buyers to secure a mortgage. As a result, the developer, Marvin Kratter, got squeezed, and in 1966 he sold about two dozen in-contract units and 135 unsold units to an investment group in a distressed bulk sale.

The late William Zeckendorf Jr.

With such a rocky start, developers were wary of condos. In fact, Manhattan’s second condo project, the 70-unit Village House at 60 West 13th Street, did not begin selling until 1970.

That, however, also turned out to be a poor starting time. The 1970s were fraught with financial difficulty — the city was struggling under a crushing debt load that led it to the brink of bankruptcy, and white flight was taking hold. (Plans for Onassis’ Olympic Tower were, however, filed in 1975.)

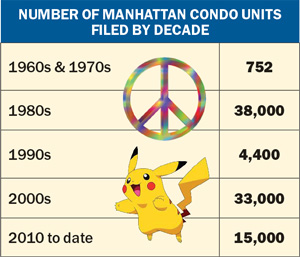

But the boom of the 1980s changed that. TRD’s analysis puts that decade into perspective. It found that developers filed plans for 752 condo units in the 1960s and 1970s, more than 38,000 units in the 1980s, 4,400 in the 1990s, nearly 33,000 in the early aughts and just over 15,000 since 2010 (either completed or in active development).

While the developers who make headlines today are often putting shovels in the ground, many of the active condo developers in Manhattan over the past 50 years converted existing buildings (whether they were hotels, offices or rentals) into condos. That may largely be because they were following the model that co-op developers had been using.

And every kind of conversion comes with its own unique set of complexities. For example, rental-to-condo conversions can be messy because blocks of units often remain occupied by rent-regulated tenants. Developers often convert as many units as they can and then sell those that remain to another investor rather than wait for tenants to move out — or die — and flip the unit into a market-rate apartment.

Source: TRD analysis of public filings

“Many of the sponsor converters don’t want to sit and wait and clip the coupons,” said Mark Zborovsky, an independent Manhattan-based broker who specializes in such units.

New construction, however, has been the driver of the high-priced condo development. Over the past five decades, 2005 saw the highest combined sellout dollar volume for condo filings, at $16 billion (adjusted for inflation). That year saw blockbuster filings like 15 Central Park West and the Plaza Hotel.

Now the question is: What’s to come? And what will we find if we do this same ranking 10 or 20 years from now?

That could depend on the developers building the more than 10,000 condo units in the Manhattan pipeline today.

Extell has more than any other developer in terms of dollar value, with upwards of $6 billion in the pipeline at just three projects.

Meanwhile, Vornado Realty Trust has more than $3 billion worth of condos at 220 Central Park South alone, and HFZ Capital Group has $3.4 billion at three projects.

Other active Manhattan developers include Ben Shaoul’s Magnum Real Estate Group, the Chetrit Group, and the Elad Group.

Still, any oversupply of inventory or a dip in the market could force developers to reduce prices and even abandon some of those projects.

As Time Equities’ Greenburger said, predicting market cycles is never an easy task.

“The day you get this idea, to selling it completely can be five to 10 years,” he said. “An awful lot happens in that time.”