When Forest City tapped FirstService Residential to manage its 363-unit modular Brooklyn rental building at 461 Dean Street in Pacific Park, at least five other companies were vying for the gig. But FirstService, one of the largest property management firms in North America, had a clear advantage. The company was already managing two other Forest City buildings: its 76-story rental tower at 8 Spruce Street in Lower Manhattan and its 36-story rental building at 80 DeKalb in Fort Greene.

The real estate investment trust had chosen FirstService for those two properties at a time when the management giant focused almost exclusively on condo and co-op buildings. But Forest City’s upper management saw potential in bringing condo-level service to its rentals.

Managing residential properties in New York City “has become much more hospitality-oriented,” said Susi Yu, the landlord’s executive vice president of development. Door staff, for instance, are trained to act on a par with what would be expected of a hotel concierge, including “staying on top of work orders, taking packages up to the residents during the day and opening car doors,” she explained.

“It’s much more than collecting rent,” Yu noted.

Of course, few property management firms do just that in 2017. Running such a business in a city of more than 8 million people can be a thankless job — one that often involves dealing with angry tenants, navigating complex city regulations and making the most out of aging mechanical systems.

Residential property management is also an industry with a checkered past, from mass corruption crackdowns in the 1990s to more recent problems, such as the property manager in Sunnyside, Queens, who filled his building’s lobby with Nazi and Confederate posters earlier this year.

But a dozen property managers interviewed for this story said the job has become more white-glove in NYC in recent years as it continues to evolve from coordinating building repairs and collecting rent to providing full-service customer relations. And tenants have grown to expect immediate responses to questions or repair requests.

“We’re not just the managers of brick and mortar,” said Susan Camerata, the chief financial officer of Wavecrest Management, a Queens-based firm with roughly 130 employees. “We’re managing the people, too, and the issues that come up. It’s become a much more intensive job.”

Within rentals, condos and co-ops alike, property managers have always been the middlemen who serve as the eyes and ears for the landlord, developer or co-op board. But they are also largely responsible for the quality of life of a property’s residents and can therefore make or break a building’s reputation.

For that reason and others, competition can be fierce and large firms like FirstService can gain and lose thousands of apartment units in the span of a few years.

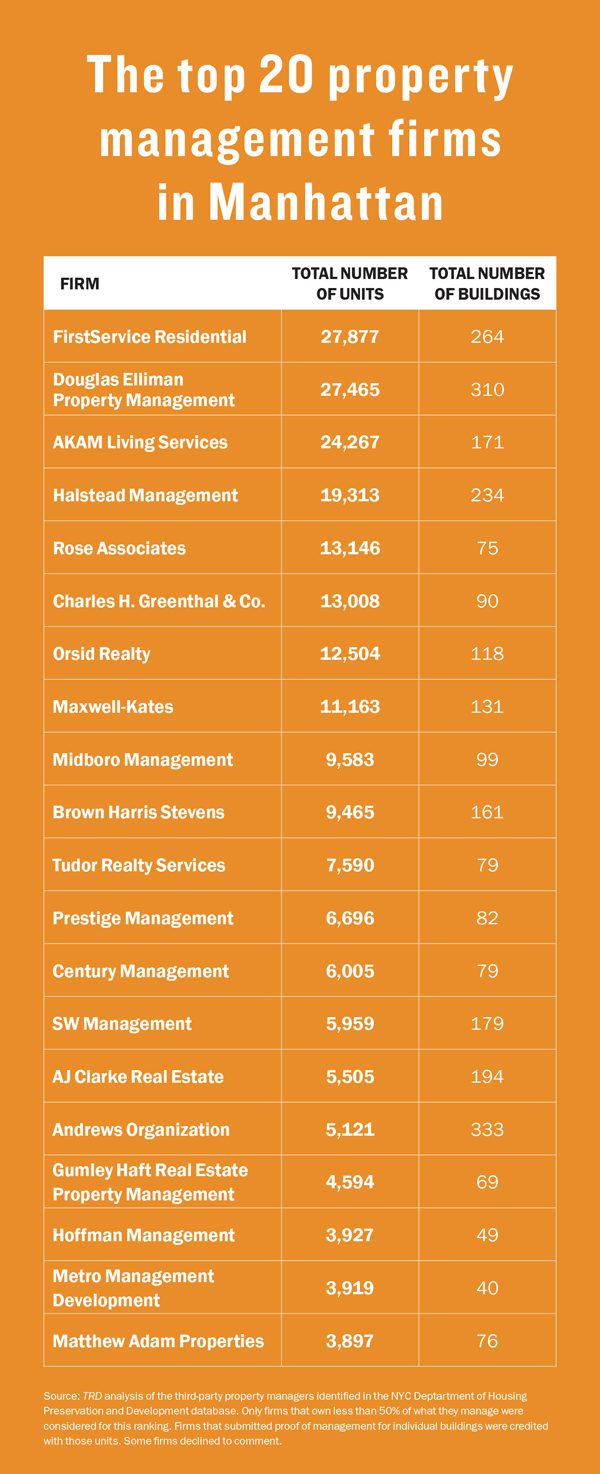

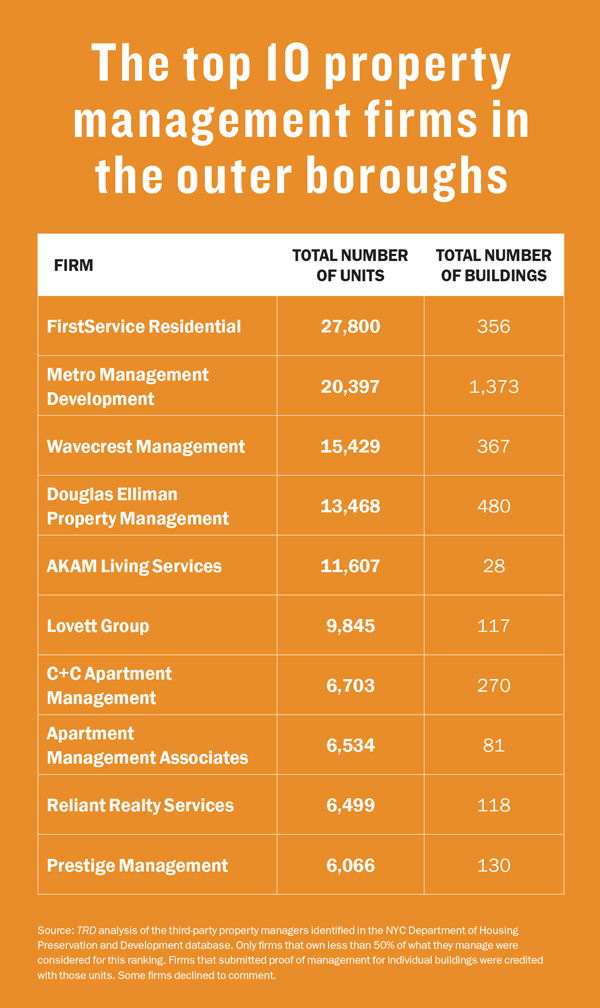

To get a closer look. The Real Deal dove into the industry this month, ranking the city’s top property management firms by the number of residential units they oversee in Manhattan and the outer boroughs. For the purposes of this ranking — which is based on data from the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development — we focused on the firms that have an ownership stake in less than 50 percent of the properties they manage.

Many of the top firms in Manhattan and the outer boroughs acquired smaller companies or scored major portfolios from competitors in recent years to gain a stronger foothold in the market. And the stakes have perhaps never been higher: The job is more complex than ever, according to industry sources, due to the increase in city regulations and rising rents. That puts even more pressure on firms to provide a higher level of services, even if clients don’t demand it upfront.

At the same time, property management is still viewed as stable ground in the volatile world of real estate — an important quality as the high-end residential market continues to soften.

“Unlike other areas of real estate, it is recession-proof,” said Neil Davidowitz, president of Orsid Realty Corp., which ranked seventh in Manhattan with 12,504 residential units in 118 buildings. “Regardless of what the value of the asset is, you need someone to manage [it]. Many businesses have difficulty collecting their fees. One good thing about property management is that we get paid every month.”

Leading the pack

FirstService dominated as the top property management firm in Manhattan with 27,877 residential units across 264 buildings, and the top firm in the outer boroughs with 27,800 units across 356 buildings.

Rounding out the top five in Manhattan were Douglas Elliman Property Management with 27,465 units in 310 buildings, AKAM Associates (a division of AKAM Living Services) with 24,267 units in 171 buildings, Halstead Management with 19,313 units in 234 buildings and Rose Associates with 13,146 units in 75 buildings.

In the outer boroughs, Metro Management ranked second with 20,397 units across 1,373 buildings, followed by Wavecrest Management with 15,429 units in 367 buildings, Douglas Elliman with 13,468 units in 480 buildings and AKAM with 11,607 units in 28 buildings.

In the outer boroughs, Metro Management ranked second with 20,397 units across 1,373 buildings, followed by Wavecrest Management with 15,429 units in 367 buildings, Douglas Elliman with 13,468 units in 480 buildings and AKAM with 11,607 units in 28 buildings.

Since TRD last did a ranking of property management firms in 2013, FirstService lost 13,396 residential units to competitors, data from HPD shows. That includes 408 apartments at Rosedale Gardens, a rental complex in the Bronx, which is now overseen by Metro Management, and 401 units at Lincoln Towers, a co-op on the Upper West Side, which is now overseen by Midboro Management (Midboro ranked ninth in Manhattan with 9,583 units in 99 buildings).

But in the same time frame, FirstService added nearly 20,000 new units to its portfolio, including Harry Macklowe’s 432 Park Avenue condo supertall. Meanwhile, the firm has acquired two other companies in the past decade: Manhattan-based Goodstein Management and Brooklyn-based Live Right Management. While FirstService’s headquarters is in Toronto, the firm’s New York office was founded in 2003 as a subsidiary called Cooper Square Realty. The office then rebranded under the flagship name FirstService in 2013.

Dan Wurtzel, FirstService’s president, said the 400-person firm has “accomplished steady organic growth over the last decade” while diversifying its “menu of client services.” On the rental side of the business, he noted, only a handful of companies in the city are equipped to properly manage large-scale, high-end buildings. And while there’s more competition in the luxury condo space, few firms can tackle an ultra-luxury tower as big as 432 Park, Wurzel added.

“You’re talking about operating a five-star hotel,” he said. “The price-point salary of a general manager who would work at a building like 432 Park is just different than the rest of the market.”

Though Forest City now uses FirstService for three of its buildings, the REIT has hired two other companies, Pinnacle and Midboro, to manage its three other residential properties in the city. “We tend to like to spread and keep the competition going between the companies to see who does better, rather than marrying up with just one company,” Yu said.

And while property management firms often rely on referrals from developers and condo and co-op boards to grow their business, poaching clients remains one of the industry’s more immediate avenues for growth. From 2013 to 2017, AKAM, a Manhattan-based firm of 162 employees, snatched several properties from Douglas Elliman, including the Toren, a 240-unit condo tower in Downtown Brooklyn, and 272 units at an apartment building at 380 Amsterdam Avenue on the Upper West Side. A spokesperson for Douglas Elliman declined to comment for this story.

AKAM’s president, Michael Berenson, said the firm’s primary growth strategy has been pitching to new development projects and replacing competitors when the developer or condo board decides to switch things up.

“AKAM has not acquired any property management firms in our 35-year history,” he said. “The larger management firms in New York have all grown their portfolios mainly due to the acquisition of other, smaller firms.”

But in the past few months alone, other firms have taken the less organic route of boosting their portfolios through high-profile acquisitions.

Dan Wurtzel, Leslie Winkler and Michael Wolfe

The development firm Rose Associates announced in June that it was selling its condo and co-op management business to Terra Holdings, the parent company of Halstead Property and Brown Harris Stevens, for an undisclosed amount. The portfolio of 8,250 units across 35 buildings represented 15 percent of Rose’s total business. A newly formed Terra subsidiary called Rose/Terra Management took over the properties. Rose Associates and Terra declined to comment.

And in August, AJ Clarke Real Estate, purchased the property management arm of the real estate services firm Fenwick Keats for an undisclosed sum. As part of the deal, AJ Clarke took over more than 40 Manhattan buildings that Fenwick had been managing and brought on five of the firm’s 12 employees. Both companies have focused on small and midsized buildings in Manhattan, so they felt the acquisition was a good fit, said Fenwick’s CEO and founder, Rob Anzalone. The two firms had been on each other’s radars for roughly 25 years, and at one point AJ Clarke was the building manager at 401 West End Avenue, where Fenwick’s former office was located, he noted.

“We weren’t actively looking for buyers,” said Anzalone, who will work as a consultant for AJ Clarke. “But we thought it was a good move for both companies.”

Cashing in

Property management can be a lucrative business, especially for the cream of the crop. The industry — which consists of 263,580 companies in the U.S. — generated $77 billion in revenue nationwide in 2016, according to a 2017 report from the business research firm IBISWorld. There are thousands of property management firms operating in New York’s five boroughs, according TRD’s analysis, though a breakdown of the number of active businesses and the revenue they generate wasn’t available.

For condos and co-ops, property managers typically charge a flat annual fee, including maintenance costs, of $500 to $1,000 per unit, according to those in the business.

The standard monthly rates that managers charge at rental properties, meanwhile, have traditionally ranged from 3 to 5 percent of a building’s rent roll. But some industry players say that model is growing outdated due to soaring rents in the city. For a rental building whose stabilized units have gone market-rate, even 3 percent can be an outrageous ask, said Jonathan West, president and chief operating officer of Charles H. Greenthal & Co. (His firm ranked sixth in Manhattan with 13,008 units in 90 buildings).

“You are going to price yourself out of the market,” he noted. “You want to do what’s right, and you want to do what’s respectful.”

As a result, many property management firms have started charging flat fees for both condo and rental properties based on the building’s size and the kinds of services the client expects. Greg Kalikow, vice president of the family real estate firm Kalikow Group — which runs its own management arm — said one of the biggest challenges property managers face is convincing clients that “cheaper is not always better.”

“If [the client] expects the service of a new Mercedes on the budget of a 30-year-old Daihatsu — those expectations are not realistic,” Kalikow said. “We always preface in our interviews that we are not the cheapest option; however, we believe that as owner-managers we have a significant advantage.”

Rental landlords who plan to hold onto their buildings for decades, or for several family generations, have traditionally handled their own property management. Those firms include the Durst Organization, Related Companies, Silverstein Properties and Douglaston Development.

Midboro’s president, Michael Wolfe, said the owners who don’t hire third-party property management firms for rental properties are often driven by a desire to “control their own destiny” — especially when it comes to new development projects.

But Michael Rothschild, the vice president of AJ Clarke, noted that property management can be very demanding, and owners of multiple properties often want to focus their energy elsewhere.

“If they have an unlimited amount of time to spend on their buildings, they’ll do their own property management,” he said. “Most of our clients don’t want to do that.”

Wurtzel of FirstService said third-party management firms boast “broader market experience” that allows for greater control over building expenses. Developers and owners need to invest heavily in personnel and infrastructure to properly manage a rental building, whereas outside firms already have those in place, he said. For condos and co-ops, property management companies are often better equipped to negotiate better energy and insurance rates, Wurtzel argued.

“The skill sets required for development and property management [in the rental business] are very different, and those differences can lead to gaps in execution and delivery,” he said.

Jeff Levine, chairman and principal of Douglaston Development as well as the firm’s construction arm, Levine Builders, and its property management arm, Clinton Management, said that while self-management can be tough work, it pays off in the long run.

“Property management is a punishing business,” he said. “The reason you do [it] is to ensure that your tenants are content, so they continue to occupy the apartment.

“Having a high quality of management maintains your asset value,” Levine added, calling that the “whole point of being in real estate.”

“Complaint department”

In the early 1990s, as the country struggled to overcome an economic downturn, recruiters found an enticing phrase to persuade young workers that property management was an attractive career choice: It was “recession-proof.”

This was the selling point that Leslie Winkler and her colleagues emphasized on college campuses in the 1990s. At the time, she worked for Penmark Realty. But the firm was eventually acquired by Halstead Management Company, where she is now a managing director and executive vice president. While the industry’s stability was compelling, Winkler said she was initially drawn to the business in the 1970s for a different reason — one that turned out to be a misconception.

“I thought you [got to see] people’s beautiful apartments, but that’s not the business,” she said. “In a lot of ways, it’s like a complaint department. Nobody tells you when you’re doing a good job.”

But Winkler said one of the reasons she has grown to enjoy her profession is the opportunity to leave an “imprint” on every new building she works on. Property managers are ultimately responsible for maintaining, and in some cases, creating the living experience envisioned by the developer, she noted.

Still, a large part of the job is making sure properties comply with mercurial city regulations and keeping violations at a minimum. Since 1998, property managers have dealt with Local Law 11, which requires buildings that are six stories or taller to undergo facade inspections every five years. Since then, other regulations have stacked up exponentially. For instance, companies that specialize in affordable housing projects, such as Wavecrest, must ensure that the residents of their buildings fall within the required income ranges.

“All the various agencies have made it a bit more arduous,” Charles H. Greenthal’s West said. “It’s a lot more paperwork, and there are very heavy fines if you’re not on your game.”

Over the last six years, the city has changed its benchmarking rules, which require certain building owners to annually measure their water and energy consumption and report it to the Department of Buildings. Starting in 2018, owners of buildings larger than 25,000 square feet and smaller than 50,000 square feet will have to benchmark for the first time — a task that will likely fall to the managers of those buildings.

In August, Mayor Bill de Blasio signed a series of smoking-related measures into law, including two that will directly impact property managers. One of the bills requires all residential buildings to create a smoking policy and share it with current and prospective tenants. The other bans smoking in common areas in buildings with less than 10 units.

The mayor also vowed in September to force owners of buildings larger than 25,000 square feet to retrofit their properties to improve energy efficiency. And industry players expect more regulatory changes on the horizon.

“It’s just a constant moving target,” Midboro’s Wolfe said. “But you’re enhancing the quality of life for people. What’s better than that?”

—Research by Ashley McHugh-Chiappone and Yoryi De La Rosa; additional research by Harunobu Coryne and Lucas McGill