While audiences and actors may be interested in what takes place inside Times Square’s theaters, landlords are often focused on what’s above them.

The historic, low-rise properties have acres of unused development rights that dangle like ripened fruit over their roofs. And since 1998, that untapped space has been easier to harvest. An amendment to a special zoning regulation passed that year gave theater owners the right to sell, or “float,” their air rights to other locations in the neighborhood, and not just combine them with adjacent parcels. The owners would simply have to pay into the specially created Theater Subdistrict Fund in order to do so.

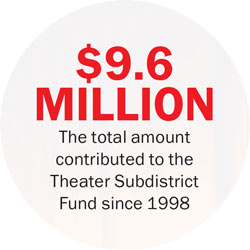

The fund, which helps create internships for minorities and others who want to get into the theater business, has collected more than $9 million since its inception with 37 grants, according to figures from the city.

But a recent city proposal to increase the fee has produced drama-worthy tensions. The Department of City Planning says the current levy of $18 a square foot, just $8 more than when the fee was instituted more than 15 years ago, should be upped to a rate consistent with actual (and not assessed) property values. That works out to about 20 percent of the sale price per square foot or 20 percent of a $347-per-foot price — whichever is higher.

Establishing a floor price would iron out discrepancies that can occur across various sales, city officials say. Under the new rules, the fee for such transactions could amount to as much as $100 a foot, based on recent transactions documented in city records.

It’s no surprise that Theater District landlords, backed by the industry trade group the Real Estate Board of New York, strongly oppose such an increase. They say a fairer price is $26 a foot, based on the rate that property values have gone up in the past two decades.

“We are concerned about having to pay a floor price if the market falls, and also the effect it will have on negotiations,” said Robin Kramer, a partner at Duval & Stachenfeld who represents the owners of the major theaters. “But our concern is also theoretical — prices should be determined by the market.”

While the proposal awaits full Planning Department approval, which many expect to happen in November, The Real Deal looked at who has benefited from these unusual and often opaque deals to understand what’s at stake going forward.

While the proposal awaits full Planning Department approval, which many expect to happen in November, The Real Deal looked at who has benefited from these unusual and often opaque deals to understand what’s at stake going forward.

The Players and plays

The three companies that control the 31 major for-profit Broadway theaters — the Shubert Organization, the Nederlander Organization and Jujamcyn Theaters — have collectively unloaded hundreds of thousands of unused square feet over the past decade.

Though the gates were opened to legal air-rights exchanges in the Theater District in 1998, the downturn that followed the dot-com bust, and the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, stifled that market for years, industry sources say.

Then in 2006, with a development boom in full swing, deals began to percolate. Since then, buyers have included major players such as Gary Barnett’s [TRDataCustom] Extell Development Company, Boston Properties and New Jersey-based SJP Properties. All in all, the zoning change has allowed for the reallocation of about 600,000 square feet of development rights, according to city records.

But while some theaters in the district, which runs from West 40th to West 57th Street between Sixth and Eighth Avenues, seem to have traded away all of their rights, others are sitting under veritable piggy banks.

Industry observers say the discrepancy exists because not all theaters are created equal. If a theater sits next to a site that an owner believes will someday be further developed, meaning the air rights could be transferred with an additional fee, he or she might wait for the best opportunity to sell. However, if a theater sits between other theaters, most of which are landmarked, there is little chance of a conventional sale.

“It’s like ice in the winter. It has no value [in that case],” said Woody Heller, an executive managing director with the commercial real estate brokerage Savills Studley.

In that case, Heller pointed out, owners have usually floated the rights to some other Times Square location.

Among recent examples, Nederlander, which owns nine theaters in the neighborhood, sold 19,800 square feet above the Neil Simon Theatre at 250 West 52nd Street in July 2015 for $9 million.

The buyers — a partnership that includes Soho Properties, MHP Real Estate Services and Hampshire Hotels Management — are building a 29-story Dream Hotel at 560 Seventh Avenue, on the corner of West 40th Street. The hotel will sit where the Broadway Theater stood before being razed in the Great Depression. The $300 million property is due for completion in 2018, a spokeswoman for the project confirmed.

Such deals, broadly speaking, underscore the zoning law’s success, said land-use attorney Howard Goldman, who in the early 1980s worked as a counsel for the Planning Commission.

Roughly a quarter of all major theaters have now participated — “a pretty healthy number,” the private attorney said. And since theater owners that float their air rights must also agree to keep producing shows, that corner of NYC’s economy has seen a boost, he added.

“I think it has been important in terms of preserving New York’s theaters as a tourist destination,” Goldman said.

The stars of the show

Proportional to the size of its real estate portfolio, Jujamcyn — which owns five landmarked theaters in the neighborhood — seems to have taken advantage of the air-rights program the most aggressively. The company has sold off a total of about 74,000 square feet above its Al Hirschfeld Theatre at 302 West 45th Street in several transactions.

In 2006, the owner of the 1924 brick structure with arches and columns along its facade sold about 58,000 square feet of air rights to SJP Properties for the construction of the Platinum, a 43-story condominium tower.

The 220-unit glass-and-steel building, which opened in 2008 at 247 West 46th Street, was one of the first developments to take advantage of the special Theater District provisions, according to industry sources.

Jujamcyn transferred another 7,000 square feet of air rights above the Hirschfeld to a site at West 54th Street and Broadway that later became the Courtyard New York Manhattan/Central Park. The 68-story, 639-room Marriott hotel, which opened its doors in 2013, has billed itself as the tallest single-purpose hotel in the Western Hemisphere. G Holdings Corporation, the hotel’s developer, paid about $1.1 million for the air rights in 2006, according to city records.

Jujamcyn transferred another 7,000 square feet of air rights above the Hirschfeld to a site at West 54th Street and Broadway that later became the Courtyard New York Manhattan/Central Park. The 68-story, 639-room Marriott hotel, which opened its doors in 2013, has billed itself as the tallest single-purpose hotel in the Western Hemisphere. G Holdings Corporation, the hotel’s developer, paid about $1.1 million for the air rights in 2006, according to city records.

The following year, Jujamcyn sold another 8,500 square feet above the Hirschfeld to Extell for $1.5 million. Extell needed the air rights for its 487-room hotel at 135 West 45th Street near Broadway, the Hyatt Times Square, which opened for business in 2013.

Similarly, Jujamcyn has auctioned off the development rights above other theaters it owns. In 2006, it sold 77,800 square feet of rights above its St. James Theatre at 246 West 44th Street to G Holdings for about $11.7 million. As with the Hirschfeld, those rights ended up at the site of the Marriott, a $320 million project.

The following year, the air above the St. James — which sports a sign framed in white lights on its roof — was once again on the block. This time, Extell paid $1.66 million for 9,500 square feet, to boost the size of its Hyatt property.

Jujamcyn’s ties to the real estate industry have become more visible in recent years. Jordan Roth, the son of Vornado Realty Trust CEO Steve Roth (see profile on page 42) and longtime theater producer Daryl Roth, took over as the company’s president and majority owner in 2009. Jordan, who had not previously worked for the theater company, bought a 50 percent stake from former owner Rocco Landesman for an undisclosed amount in 2009. Landesman then sold most of his remaining stake to Jordan in 2013.

Goldman, sympathetic to theater owners, said he worries that the proposed zoning change will cause real damage in a real estate downturn.

“One of these days, in the not-too- distant future, the market will head south again, and that’s when it will have a real impact,” he said.

Representatives for Jujamcyn, Extell, SJP and G Holdings did not return calls for comment.

The climax builds

With the new city proposal to levy close to 20 percent for each air-rights sale, the fees on those transactions would be significant.

In February 2016, for instance, Extell bought 42,000 square feet of air rights from the not-for-profit Helen Hayes Theatre for nearly $20 million, or $475 a foot, which Barnett allocated to a condo-hotel at 1710 Broadway.

Under the current fee rate, Second Stage Theatre — the owner of Helen Hayes since last year, when it bought the tiny 600-seat hall from Martin Markinson and Donald Tick for about $25 million — had to shell out an additional $18 a foot for the Theater Subdistrict Fund. Under the proposed fee hike, Second Stage would have had to kick in about $95 a foot.

Under the current fee rate, Second Stage Theatre — the owner of Helen Hayes since last year, when it bought the tiny 600-seat hall from Martin Markinson and Donald Tick for about $25 million — had to shell out an additional $18 a foot for the Theater Subdistrict Fund. Under the proposed fee hike, Second Stage would have had to kick in about $95 a foot.

And while the money would benefit certain pockets on and off Broadway if the proposed fee changes come to pass, some in the real estate business say the hiked fee could chill the market.

“Most special districts like the Seaport or West Chelsea impose flat fees,” which are more reasonable than in the Theater District, Duval & Stachenfeld’s Kramer said. The land-use attorney said that values can vary wildly from block to block, making a one-size-fits-all minimum unfair.

She added that some theaters are better positioned to sell — namely, those where development is the most unlikely, on strips like West 44th Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Midway down the block, a large cluster of theaters owned by the Shubert Organization is essentially off limits for construction projects due to each building’s landmark status.

Shubert — the largest theater landlord in Times Square, with 17 properties — has put many of those properties’ air rights on the market. The air above the Broadhurst Theatre, a 1,156-seat terracotta-trimmed venue that opened in 1917, has been chopped up several times.

Among its first transactions, Shubert sold 55,000 square feet to Extell for about $11 million in 2007 for the developer’s Hyatt Times Square, city records show. Then, in 2009, the theater owner sold 9,500 square feet for $3.8 million to Stanford Hotels, which is building the Luma Hotel Times Square at 120 West 41st Street.

The glassy spire, with 26 floors and 130 rooms, is scheduled to open in March 2017. Some of the air rights for the building have also come from Shubert’s white-brick Booth Theatre at 222 West 45th Street, according to city records.

The theater owner sold another 18,000 square feet to Ark Partners for about $4.1 million in 2011. Ark used the development rights for its Viceroy Central Park, a 240-room hotel at 120 West 57th Street, on the outer lip of the Theater District. And in 2014, using air rights above the Broadhurst and the adjacent Majestic Theatre, Shubert sold 58,400 square feet to Algin Management for $17.6 million.

Algin is building a massive condo on the site of the former Roseland Ballroom concert hall. That project could potentially rise higher than 59 floors with the additional air rights.

Representatives for Shubert, Ark and Algin did not return calls for comment.

Attorney Paul Selver, co-chair of the land-use practice at Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel, who advised on the Roseland deal and others in the area, said that while developers are able to buy the rights and build taller, theater owners could quickly hit a ceiling with the increased fee.

“It’s tough to make it as a theater owner,” Selver said. “It’s important that there is some kind of compensation for these zoning restrictions.”

But lost in the discussion, perhaps, is how the increased fees could lift the fortunes of aspiring Broadway stars.

In the past, the grants, which are awarded by the Theater Subdistrict Council, have benefited nonprofits including the Classical Theatre of Harlem, the Pregones Theater and the New Dramatists.

Another beneficiary has been Rosie’s Theater Kids, an organization that focuses on introducing lower-income grade-school students to the performing arts. It received a total of $200,000 in grants from the local fund in 2009 and 2012, some of which went to 15- week theater programs, the group’s co-founder and executive director Lori Klinger said.

Because the grants covered only about a third of the cost of those programs, a boost in funding would be welcome, Klinger told TRD. “It has been so meaningful for us to change the trajectory of kids’ lives,” she said.