It was like the meeting of the five families.

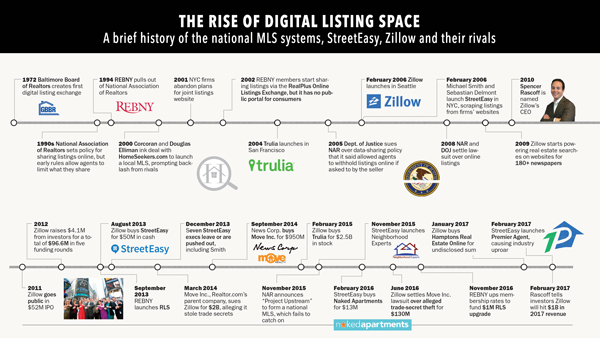

In 2001, the dons of New York City’s residential brokerages all gathered to discuss whether they should band together to create a formal Multiple Listing Service that would act as a clearinghouse and provide consumers with a searchable listings database for the first time.

But tensions were running high. The meeting came after nearly a year of industry infighting that was sparked when the city’s two biggest firms — the Corcoran Group and Douglas Elliman — joined forces and attempted to launch an MLS on their own.

The backlash to that move from other firms was so great that the two giants were stopped in their tracks.

When the finger-pointing subsided, there was a consensus that some sort of unified action was required to create a desperately needed MLS. It seems that the “Battle of 2000” — as the industrywide fight was affectionately dubbed — had finally come to an end.

But 17 years after that now-infamous meeting, New York City still does not have a consumer-facing MLS.

Instead, the city’s residential firms have a fractured and complicated system with disparate listings platforms — and no industry-sponsored way for the general public to scroll through a comprehensive list of properties that are on the market.

While that reality has long been viewed as a major industry failing, it is now coming back to bite residential firms in a big way. And the blame game is in full effect once again.

Robert Reffkin, CEO of the four-year-old venture-capital-backed brokerage Compass, took a not-so-veiled shot at Elliman and Corcoran last month, blaming them for the lack of a New York MLS.

“When you have a few companies that have 50 percent market share, that’s too much power,” he said at an event hosted by the New York Real Estate Academy. “They can effectively say no to anything that’s not going to help them.”

Today, the industry is in the thick of a battle with the listings platform StreetEasy, a fight that hit a new level of intensity last month when the company unveiled a controversial program called Premier Agent (see related story). The Premier Agent program directs users to agents who advertise next to a listing rather than agents who hold the listing.

It’s impossible to analyze the industry’s current predicament without looking back at how StreetEasy came to power — and how the industry built such a reliance on StreetEasy in the first place.

And virtually everyone agrees that the industry would not be in this situation if it had created a consumer-facing MLS of its own before StreetEasy launched in 2006.

“We’re finally seeing the effects of what happens when you don’t control your own content,” said Donna Olshan, who runs an eponymous boutique Manhattan firm and was at that fateful meeting in 2000. “We created the monster of StreetEasy, and now it’s hard to get away from it.”

Trust thy competitor?

For as long as there have been residential brokerages in New York City, there has been a lack of trust among them.

For years, brokerages — especially the big and powerful ones — have guarded their exclusive listings as if they were the secret Coca-Cola formula or classified national-security information.

That’s partly because many of them came of age in a different era — during a time when the market was dominated by townhouses and co-ops, and managing agents had the inside track on who was selling what. Buying in Manhattan was reserved for a more select group of people, and the rentals were an even bigger share of the market than they are today.

In the late 1980s, when brokers landed listings, they printed the information on a small card and filed it away at their own company. Co-broking with another firm was virtually unheard of.

As technology improved, that system gave way to manually uploading listings into computers and faxing the information to another broker when word of a listing got out.

By the 1990s, MLS systems began popping up in other U.S. cities, allowing brokers to easily share listings. But New York brokers resisted, largely to avoid having to split commissions with competitors.

Then came the dot-com era, which generally coincided with the first wave of widespread condo construction in New York City. Both were game changers for the residential landscape.

In the face of those changes, Corcoran, headed at the time by Barbara Corcoran, and Elliman, headed by Alan Rogers, quietly began formulating plans to create a consumer-facing MLS.

In 2000, they inked a deal with California MLS operator HomeSeekers.com to build it and announced the initiative with a splashy story in the New York Times.

“This new MLS system is one of the most exciting new developments in New York real estate in years and will have a tremendous impact on the way real estate agents conduct their business,” Corcoran’s Pam Liebman said in a statement to the paper at the time. “As the leaders in Manhattan residential real estate with close to $5 billion in combined annual sales, the Corcoran Group and Douglas Elliman are thrilled to be spearheading this long-awaited, ground-breaking venture.”

But in the industry, the announcement dropped like a lead balloon.

Their competitors were incensed.

While Corcoran and Elliman invited all the other firms to participate, it was a for-profit endeavor that was plotted without the knowledge of other companies. Adding salt to the wound was that Corcoran and Elliman would charge the other firms to feed their listings into the new system.

Engel & Völkers’ Stuart Siegel — who was with Sotheby’s International Realty at the time — told The Real Deal that the structure of the system was problematic.

“We would be paying our competitor to handle our listings and data,” he said. “It was inconsistent with the spirit of an MLS, in which all firms should get equal stature and have shared responsibility.”

Olshan agreed, saying that the “presumption was that everyone would have to give them a piece of their own businesses.”

“You’ve never seen a bunch of people madder than a hatter than this group,” Olshan said.

Ultimately, the only two firms to sign on were Halstead Property and Bellmarc Realty Group, but that wasn’t enough.

Paul Purcell — currently the managing director of William Raveis NYC, but then an executive at Elliman who later went on to run that company’s New York operation — said the outcry was like a scene from a classic horror film.

“It was like a Frankenstein movie where the villagers run up the hill with their torches to kill the monster,” he said. “It was stupid.”

Purcell said he didn’t understand what the opposition was so riled up about.

“They were so antiquated in their thinking,” he said, referring to the heads of the boutique firms. “I called them the ‘club women.’ They all go to the country club and sit on committees, vote things down and get so scared about change. They just didn’t have that vision for the future.”

Sources throughout the industry say that Corcoran and Elliman made one fatal mistake: They excluded William and Arthur Zeckendorf, who own Brown Harris Stevens, in their plan.

Instead, William Zeckendorf galvanized the opposition firms, which all met at his office to formulate a game plan. In addition to BHS, those firms included Sotheby’s, the now-defunct Coldwell Banker Hunt Kennedy and a bunch of boutique firms like Fox Residential and Kleier Residential (then known as Gumley Haft Kleier). Zeckendorf was said to be particularly angry that Corcoran and Elliman were making an end run around the industry’s main trade group, the Real Estate Board of New York, which had been batting around the MLS idea for years.

The Zeckendorf-led opposition ultimately decided to try to create a competing MLS.

Roughly a half-dozen opposition firms acquired the domain name NYMLS.com, which was nearly identical to the name Corcoran and Elliman were using: NYCMLS.com.

They then tapped a small Manhattan software firm named Gabriels.net, whose founder, Michael Gabriel, had developed a software program called Real Estate Exchange, which he’d been selling to individual companies for years to power their back-end listings systems.

At the time, Liebman was quoted saying the opposition was simply upset that they hadn’t thought of it first. She singled out BHS, telling the Times that the heads of the firm were “furious they didn’t start this.”

Last month, Liebman defended the move to launch the MLS, saying the smaller firms were unjustly afraid of being steamrolled.

“They thought we would crush them,” she told TRD. “But it would have leveled the playing field.”

Cooling of relations

In early 2001, after months of negotiations, tensions finally began to ease, paving the way for the abovementioned meeting.

With the help of REBNY’s then-president, Steve Spinola, Corcoran and Elliman agreed to drop plans to make their listing service a for-profit business.

Instead, the two brokerage giants proposed forming a board, which would be made up of elected representatives from each firm, with larger firms getting more voting rights, Liebman said. “Everybody would have owned it,” Liebman recalled. “You would just have paid a fee based on what listings you were putting in there.”

But when it came time to iron out the deal’s finer points, negotiations fell apart. The larger firms simply couldn’t see the benefit of creating a system where their listings would get the same billing as listings from smaller firms, especially because at the time, their own websites were gaining serious consumer traction. The thinking went like this: Why did they even need an MLS when consumers were coming directly to their websites?

“It was a different world,” Halstead’s current president, Diane Ramirez, told TRD. “We were like babes in the woods. Back then, we thought that if we created the best website in the world, they would all come to us. The decisions we made then were right based on what we knew at the time.”

Meanwhile, as the industry was mired in bickering, Gabriel licensed his technology to the Times, which then became a de facto MLS with firms taking out listing ads and consumers searching for properties. And a few years later, StreetEasy launched and began scraping listings from all firms’ websites. The move ushered in a new level of transparency in the traditionally clubby Manhattan real estate world. Not only did it give smaller firms access to all the same listings big firms had, but it also established one website for consumers — who until then needed to log onto different firms’ sites to see listings.

After initial pushback from the brokerages, many came to embrace StreetEasy, which was suddenly driving traffic to their websites and putting more eyeballs on their listings.

Soon nearly all firms began feeding their listings to StreetEasy, which was posting them for free and only charging to “feature” properties and advertise new developments.

Some of the brokerages were actually relieved when StreetEasy took the lead on creating an MLS alternative, especially given that the company seemed happy to work alongside the brokerage community.

“They said this is not my business, my business is selling real estate,” Engel & Völkers’ Siegel said.

But Zillow’s 2013 purchase of StreetEasy changed the game.

The Seattle-based company had a different business model — based more on broker advertising than subscriptions. In addition, as a public company, Zillow has a laser-like focus on profitability.

It’s not hard to draw a line between the success of StreetEasy in New York and the lack of an MLS here.

“Because our industry didn’t come together and control our own information in the year 2000, these aggregators came about,” BHS President Hall Willkie said.

Purcell said the industry has little right to be “outraged” by StreetEasy’s controversial Premier Agent feature.

“Shame on us in New York that we can’t play nicely in the sandbox,” he said.

Four months vs. one day

While the industry could not come to terms to create a consumer-facing MLS, the “Battle of 2000” led instead to the creation of a broker-only system run by REBNY called the RLS.

REBNY partnered with the real estate tech platform RealPlus in 2002 to deliver a service known as R.O.L.E.X., which sends listings for free to more than 500 firms. The service connects to several external companies — including RealPlus, On-Line Residential and proprietary systems owned by Corcoran and Elliman, known as Taxi and Limo, respectively.

In 2012, after nearly a decade of REBNY working with RealPlus — which is partially owned by the Zeckendorfs — the real estate trade group tapped the national company Stratus Data Systems to take over.

REBNY is now trying to improve the Stratus interface.

John Banks, who replaced Spinola as REBNY’s president in 2015, said the system may eventually be public-facing. “But that’s not the priority at this stage,” he noted.

And sources are not confident that this latest battle with StreetEasy will push the industry once and for all to unite and create an MLS.

“They don’t have the resources to create a competition [with StreetEasy],” said Jonathan Miller, founder of appraisal firm Miller Samuel. “If they all pulled their listings in protest, that would probably have a more powerful impact. There’s motivation to work together. They’re all upset.”

Compass’ Reffkin said companies like Zillow-StreetEasy are nimbler than NYC’s fractured brokerage industry.

“They’re much better than our industry,” he said. “We as an industry can’t act that fast because we’re not one person … and because of a lack of trust. What takes us four months takes them one day.”

Even if REBNY launched an RLS for consumers, it would have an immediate disadvantage.

“You’re talking about a sophisticated technology and having a trade organization run it like a volunteer fire department,” Olshan said.