With all of the trades, windfalls, setbacks and wildcards, New York City’s rental market can often resemble a big round of Monopoly. But in the real world, the wins and losses are far greater than what can be counted in multicolored cash.

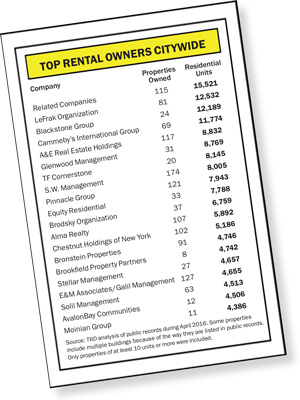

This month, The Real Deal pored through public documents gathered in April to come up with a first-ever, exclusive ranking of who owns the most rental apartments in New York City. What we discovered was that just 20 landlords hold more than 150,000 of the city’s approximately 2.2 million rental units. And those properties netted their owners more than $2 billion in annual income as recently as 2014, according to an analysis of New York City Department of Finance tax records.

To get a clearer picture of which portfolios bring in the most cash, we created a list of each owner’s current rental portfolio. We then calculated the pre-tax net income using property tax assessments and subtracted the tax bill — accounting for tax breaks like 421a — for every building we reviewed.

(We only ranked for-profit developers and owners and excluded developers that predominantly build affordable housing with government subsidies — a class of owners more difficult to track in public records.)

Related Companies ranked No. 1 with at least 15,521 apartments, predominantly in Manhattan and the Bronx. The LeFrak Organization came in second with at least 12,532 units, the bulk of which come from the eponymously named LeFrak City in Queens. Private equity giant Blackstone Group took the No. 3 spot with at least 12,189 apartments in New York. Cammeby’s International, a portfolio built by Rubin Schron over 50 years, was the fourth-largest landlord, with at least 11,774 apartments. And A&E Real Estate Holdings came in fifth. Its 8,832 units were mostly acquired in the span of just five years.

It should be noted, however, that many of the landlords on this list may own even more units than TRD was able to identify because of the lack of transparency in public property records, especially when multiple owners exist.

Still, the properties owned by the city’s biggest landlords represent almost every era since the beginning of the 20th century and can be found in virtually every corner of the city. From pre-war walk-ups in the South Bronx to modern skyscrapers that will soon open at Hudson Yards, the reach these landlords have over New York’s rental landscape is extraordinary. And in most cases, those portfolios are growing.

Indeed, last year marked a record year for apartment building sales, with $19 billion dollars in transactions, exceeding the previous record set in 2014 by 52 percent, according to the commercial real estate services firm Ariel Property Advisors.

Prices rose in every city submarket and top-owning landlords such as Related and A&E added more than 1,000 units to their portfolios. Cammeby’s, meanwhile, picked up a 160-unit rental at 1501 Lexington Avenue for $92 million. And Blackstone blew everyone out of the water on the acquisition front, adding more than 12,000 units.

And if these owners aren’t buying, they’re building. AvalonBay Communities, a publicly traded real estate investment trust, has completed or begun more than 3,000 rental units in the city within the last 10 years. TF Cornerstone, the real estate firm run by brothers K. Thomas and Frederick Elghanayan, has developed around 4,000 rental units in the last six years, including the 1,028-unit 606 West 57th Street, slated to open in 2017. That building will contain more than 200 units of affordable housing to meet the requirements for 421a — the primary government tax credit these builders have depended on to construct rentals for so long.

But that tax credit very publicly expired six months ago, and the much-anticipated emergence of its replacement is uncertain at best.

Meanwhile, tenant protections on rent-regulated units, which make up a large portion of the recently traded apartment buildings, have tightened, and some Albany politicians have pushed for more limitations on rent hikes. Other observers say that current regulations and protections pale in comparison to the powers building owners still have at their disposal.

Either way, the landscape of New York City’s rental market is rapidly changing, with a growing number of large real estate and financial firms stepping into an arena where local owners have long dominated.

Starting at the bottom

Though Related, LeFrak, Blackstone, Cammeby’s and A&E share space at the top of the list, they each got there in categorically different ways. Some gradually built, while others bought in mass -— and some did both. In addition, some are family operations, while others are global corporations in which New York real estate is just one piece. But the one recurring theme is that many found their footing in the outer boroughs and outside of the high-flying market-rate business.

“Most of these companies have their roots in affordable housing,” said Madison Capital’s Michael Stoler, host of the CUNY TV show “The Stoler Report,” a weekly panel on New York business. “It was an easy way to enter the business without big expenses and without raising significant equity.”

For many of the largest owners of apartment units, the path to the top has indeed been built from more modest beginnings. But as their companies grew, so did the scope of their developments and acquisitions, moving from affordable outer-borough buildings to luxury residential and commercial properties in Manhattan and elsewhere.

Related’s Stephen Ross started his career as a tax attorney and traded it in for real estate when he launched the Related Housing Companies in 1972. With the savvy he had from working in tax law, Ross found a way to syndicate government tax shelters, providing an additional source of income on top of developer fees.

“Affordable housing was the best way to learn how to become a developer because you didn’t really have market-rate risks in terms of running your units,” Ross said on Stoler’s “Building NY” television show in 2011. Related, of course, is now one of the biggest developers in the city, with a number of luxury condo and rental towers, including MiMa, the 63-story luxury rental on West 42nd Street. Related completed the tower in 2012 and sold the top 13 floors to Kuafu Properties last year. Apartments in the building regularly rent for more than $5,000 a month.

Meanwhile, when the LeFraks arrived from France in the 19th century, they quickly started buying modest walk-up buildings in Williamsburg.

Maurice LeFrak had been a developer in France as early as the 1840s and his son, Aaron, carried the family business over to America, where he began developing in the early 1900s. His grandson, Samuel, developed his first building while still in college in 1938. And in the 1960s, the LeFrak Organization went on to build LeFrak City, a kind of Stuyvesant Town for Queens with 4,650 apartments spread among 20 buildings. Since that time LeFrak has spread its reach to New Jersey, Florida and California. The firm has also acquired office properties in Manhattan, and its CEO, Richard LeFrak, has become a billionaire in the process. But through it all, rentals have remained the core of the firm’s business. “I’ve done condos, but I consider it the stupidest form of real estate investment that exists,” LeFrak told TRD earlier this year.

Maurice LeFrak had been a developer in France as early as the 1840s and his son, Aaron, carried the family business over to America, where he began developing in the early 1900s. His grandson, Samuel, developed his first building while still in college in 1938. And in the 1960s, the LeFrak Organization went on to build LeFrak City, a kind of Stuyvesant Town for Queens with 4,650 apartments spread among 20 buildings. Since that time LeFrak has spread its reach to New Jersey, Florida and California. The firm has also acquired office properties in Manhattan, and its CEO, Richard LeFrak, has become a billionaire in the process. But through it all, rentals have remained the core of the firm’s business. “I’ve done condos, but I consider it the stupidest form of real estate investment that exists,” LeFrak told TRD earlier this year.

The other three owners in the top five — Blackstone, Cammeby’s and A&E — operate almost exclusively through acquisitions rather than development. Part Silicon Valley investor, part New York real estate scion, A&E has quickly become the city’s fifth-largest landlord through multiple portfolio purchases in recent years. In 2015 alone, the company acquired $800 million in New York rental properties, including the $201 million Riverton Houses complex in Harlem in a deal brokered with the city. John Arrillaga -— the ‘A’ in the company’s name — is the son of California real estate developer John Arrillaga, Sr. In 2011, he joined forces with Douglas Eisenberg — the “E” — a former executive at New York landlord Urban America, which was founded by his father, Phillip Eisenberg.

Meanwhile, Cammeby’s had amassed $13 billion in assets by 2015, according to Real Capital Analytics. And, like some other companies on this list, much of that exists outside of the Big Apple, including more than 180 nursing homes in more than a dozen states, as well as millions of square feet in office space nationwide. Like others on the ranking, Schron’s unit count is likely even higher than that 11,000-plus TRD identified. That’s because he is known for partnerships — with the likes of Steve Witkoff and Jamestown Properties, among others — that may obscure his ownership stake in some properties.

Schron has voraciously acquired existing multifamily housing over the years, including 885 units at Trump Village in South Brooklyn. But the company now appears to be heading in a new direction.

Last year, it filed for its first major ground-up construction project, a 544-unit tower on Neptune Avenue in Sheepshead Bay, which some believe is the path that Schron’s sons, Avi and Eli, will take the company on going forward.

Blackstone -— which owns more U.S. homes than any other firm in the country -— is now also well on its way to becoming the largest landlord in New York City. Founded by Stephen Schwarzman, the company made its largest splash here last year with its $5.4 billion joint-venture purchase of Stuy Town. Blackstone bought the 110-building, 11,250-unit apartment complex with the Canadian investment firm Ivanhoe Cambridge. And Blackstone has snapped up other residential properties as well, including the 24-building Caiola portfolio, which it bought in partnership with Fairstead Capital last summer for $700 million. Blackstone’s co-head of U.S. acquisitions, Nadeem Meghji, told TRD that the firm has no specific goal of becoming New York’s largest rental landlord, but the company is always on the hunt for new investment opportunities.

“Pricing is higher today than it was four or five years ago, but we still tend to believe that cash flow in New York City is going to outpace many other geographies just because it’s so hard to build here,” Meghji said.

Even as some of the top rental landlords in New York have moved from deals in lower-income housing to deals in the luxury world, below-market rentals still make up a significant amount of many of their portfolios.

Even as some of the top rental landlords in New York have moved from deals in lower-income housing to deals in the luxury world, below-market rentals still make up a significant amount of many of their portfolios.

Pass Go & collect $200M

For some, the lower end of the market was a way to get started in the business, but for others it’s been a generations-long business plan.

Take Bronstein Properties, which came in at No. 14 with more than 4,700 rental units across three boroughs. Nearly all of the firm’s units are either currently or were previously subject to rent regulation — an acquisition strategy the firm’s principal Barry Rudofsky described as his “MO.”

“When my father-in-law started the business, his favorite neighborhood was Sunnyside, Queens,” Rudofsky told TRD. “Everyone knew about Astoria, but people didn’t really know about Sunnyside. So it was sort of, like, not quite the next neighborhood but the neighborhood after that to revitalize.”

Historically, there’s no question that owning rent-stabilized housing has been a profitable business. The average net operating income for rent-stabilized apartments rose more than 42 percent (adjusted for inflation) from 1990 to 2014, according to the most recent income report from the city’s Rent Guidelines Board. But since 2001, those incomes have risen just 4.4 percent.

“In today’s market it’s challenging to increase NOI overnight,” said Chad Tredway, JP Morgan Chase’s managing director of commercial term lending, one of the city’s most active multifamily lenders. “Investors are now expecting that it’s going to take a longer period of time to increase NOI from their properties.”

Many landlords and other industry insiders increasingly say that getting the kind of rent increases that owners have historically depended on to boost NOI has become more difficult. Real estate attorney Luise Barrack of Rosenberg & Estis cited the increase in the destabilization threshold — which jumped to $2,700 from $2,500 in 2015 — as a major factor that makes racking up returns harder. Tacked onto that change was another requirement stating that the first lease inked after the $2,700 threshold is met must also be rent stabilized — even after a landlord jacks up the rent.

“You now have a circumstance where owners previously bought multifamily housing in order to reposition, take units and bring them over the luxury deregulation threshold so they could go to market,” Barrack said. “In 2015, there was a reset so that if the last tenant wasn’t over [the deregulation threshold], the next tenant, even if they’re coming in at $4,000, is a rent-stabilized tenant.”

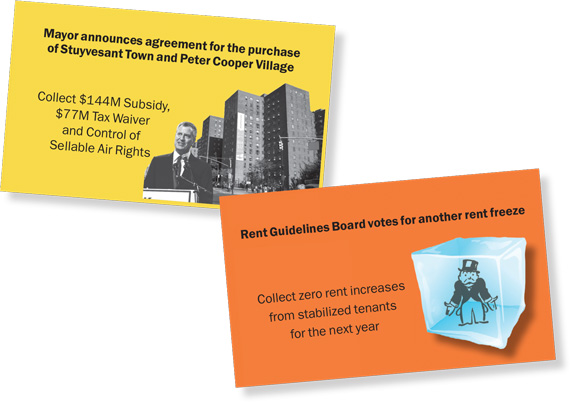

The measure, part of the Rent Act of 2015, also lowered the maximum monthly rent hike landlords can charge for making major capital improvements to buildings. And in another blow to rental building owners, the Rent Guidelines Board froze the annual rent hike for stabilized apartments for an entire year last June. The board is widely expected to do the same thing this summer. And sources said the state-run Division of Housing Community and Renewal’s Tenant Protection Unit — which conducts audits and investigations of landlords to insure legal compliance and catch instances of harassment and fraud — has cranked up the enforcement pressure.

The state’s top authorities have cracked down as well. In the last year, Governor Andrew Cuomo has come down on landlords that receive the 421a tax abatement but do not keep their apartments rent stabilized — an action that sought to return rent stabilization to more than 2,400 families citywide. He also ordered that 50,000 units receiving J-51 abatements that were illegally removed from rent stabilization be restored. That plus the landmark 2009 New York Court of Appeals case over wrongful deregulation of apartments receiving the J-51 tax abatement at Stuy Town made a gray area far more black and white for would-be investors of rent-regulated properties.

“You have to be very thoughtful with regards to underwriting,” said Adam Roman, chief operating officer of the New York real estate firm Stellar Management, which ranked No. 16 by number of rental units owned. “A lot of our underwriting we base on the actual performance we’re seeing in our portfolio and in our assets today.”

During the financial crisis, however, Larry Gluck’s Stellar owned assets that were over-leveraged. It defaulted on mortgages at the Riverton Houses, where debts outweighed rental income, and its lenders foreclosed. Roman said today the company is focused on long-term multifamily investments. “We don’t take an aggressive or speculative view,” he said.

Hitting the NOI target

Despite today’s challenges, the top landlords are netting hundreds of millions of dollars on their portfolios.

TRD’s analysis looked at owner’s current portfolios but had to rely on 2014 revenue figures because those were the most recent numbers available. While the owners might not have owned all of the same buildings back then that they do today, the goal was to assess what their current-day properties are likely throwing off. In some cases, buildings in their current portfolio were under construction two years ago and still are today. In those cases, the income estimates used on the ranking are based on an analysis of city tax records that offer a window into what the property would produce today.

Not surprisingly, the firm that owns the most apartments in New York also brings in the most net operating income, according to TRD’s analysis of property tax data.

The analysis estimates that Related’s rental portfolio -— which includes a number of properties that are still under construction — could generate nearly $312 million in NOI annually.

And although the city NOI figure does not allow for the deduction of every conceivable expense, nor does it account for debt payments, it does give a good impression of the income-producing potential of these properties.

The second-highest-netting landlord, Glenwood Management, known for white-glove luxury properties, brought in some $250 million from its more than 8,700 apartment units. Equity Residential and TF Cornerstone came in third and fourth on the NOI ranking. Blackstone, factoring in its 2015 Stuy Town acquisition, ranked fifth.

The now-expired 421a tax program, which cost the city more than $1 billion in tax revenue in 2014, according to a report from the nonprofit Community Service Society, has been key for making new rentals profitable for the city’s top developers.

For the 2015-2016 tax year, TF Cornerstone owed approximately $25.5 million in property taxes across its more than 8,000 apartment portfolio, a figure that would have been closer to $82 million without 421a and other tax exemptions. The company has at least six addresses across Manhattan’s Financial District, Chelsea and Hudson Yards neighborhoods that are currently receiving the 421a benefit and four buildings in Long Island City that owed no property tax at all, together saving TF Cornerstone tens of millions of dollars.

Related, Glenwood and Equity Residential are also major recipients of 421a. Yet the majority of Glenwood’s high-earning portfolio does not currently benefit from tax exemptions. That explains why Glenwood owed the most taxes on TRD’s list — an estimated $101.7 million for the 2015-2016 fiscal year.

But companies with newer buildings in the 421a program are seeing some of the biggest windfalls.

AvalonBay, for example, received the tax break on 11 of the 12 buildings in its New York rental portfolio. The company’s estimated NOI for the buildings was more than $115 million — including new development projects like the 800-unit-plus 100 Willoughby Street in Brooklyn.

AvalonBay’s tax bill on that $115 million was an estimated $7.5 million. That was the lowest tax percentage that TRD found of any firm on the list — again all based on 2014 income and tax figures.

Without the tax cushion provided by 421a, the rental pipeline is expected to contract dramatically. New permits issued for residential construction are already down significantly in 2016 from 2015 highs, when developers rushed to get projects approved before 421 expired. The number of new residential projects submitted to the Department of Buildings for consideration so far this year has also been modest.

“I think without incentives for developers to build housing, both affordable and market rate, we’re going to have a greater housing crisis than we currently have,” said Jeremy Shell, TF Cornerstone’s head of finance and acquisition.

The renter’s fate

Despite the potential risks, 2015 was still a record year for multifamily housing trades. And of New York’s 2.2 million rental units, about half are still rent stabilized. Tens of thousands of those apartments have been sold too, and none more famously than Stuy Town.

The purchase of the complex by Blackstone and Ivanhoe Cambridge was sealed with the help of the city, which guaranteed the partners over $200 million in financial incentives in return for keeping 5,000 units rent stabilized.

The Stuy Town deal raises an important question for New York’s rental future: With multifamily properties trading at record highs, are direct government subsidies to private landlords the only thing that can convince new owners to keep units rent stabilized -— and keep New York from becoming a market-rate city for the wealthy only?

“It seems to me there’s no other way,” said Alan Wiener, group head of Wells Fargo Multifamily Capital, which lent Blackstone and Ivanhoe Cambridge $2.7 billion for their Stuy Town purchase.

Wiener and other industry insiders said the city’s deal with the two investment giants was the right thing to do from a public-policy perspective.

At Stuy Town, Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration also ponied up about $221 million in financial sweeteners — including a $144 million pseudo loan that does not require any repayment. Those incentives balance out any cash-flow reductions Blackstone faces for agreeing to keeping 5,000 units rent stabilized for 20 years.

“What they got from the city for the agreement was pretty good for them, so they can absorb some crimpling on their future rental income,” said housing analyst Tom Waters, who works for the Community Service Society.

Additionally, Blackstone has placed Stuy Town in its “core-plus” fund for longer-term investments that do not need to be sold in less than 10 years, further indicating that the company sees the asset as a longer-term hold.

“This has to be a city where people of limited means can live, so I think government has to have policies that are supportive of that,” said Wiener. “Whether that’s changing the way real estate taxes are allocated, whether it’s providing subsidies, those things are very important.”

But many of the city’s rent-regulated apartments are not locked into special agreements with the city that ensure they will stay affordable in the long term — a major concern for activists and tenants. “We are still seeing a huge speculative and displacement-oriented strategy across the board in affordable and rent-stabilized buildings across the city,” said Benjamin Dulchin, head of the affordable housing coalition the Association for Neighborhood Housing and Development. “We are consistently seeing buildings being sold for more than the current rent roll suggests they should sell for, which suggests that the plan is harassment.”

While regulation has tightened in the last decade, and institutional lenders are significantly less likely to participate in risky multifamily acquisitions, Dulchin said he believes that old habits — those that come with high-volume, speculative investing based on the turnover of rent-stabilized apartments — die hard.

“It’s correct to say that it’s not 2003 and that the worst excesses, where there was almost no relationship between what buildings were selling for, what lenders were willing to lend and what the actual income pace and value of the building should be, have passed,” he said. “The lesson I think the industry drew from that was … use the basic tools, keep the basic pieces of the strategy but don’t take it quite so far.”

What comes next?

Before even rolling the dice on staying in the rental game, each company on TRD’s list of top landlords has mapped out a strategy for the near future, given the changing landscape.

Blackstone is betting that new construction rental supply will never be significant enough to harm rental price growth, especially when the amount of current rental stock that is being converted into condos is taken into account.

“When you have virtually no new supply of rentals net of condo conversions, that’s part of why we expect to see continued cash-flow growth,” said Blackstone’s Meghji. “We think rental supply has been modest and will remain reasonably modest.”

TF Cornerstone, meanwhile, is considering a further push into condo development — a move influenced by the lack of tax incentives and the high cost of land.

“Under the current environment where we don’t have 421a, we’re forced to think outside of our primary box and think about for-sale housing,” Shell explained.

That stance has become the refrain for many of New York’s most active rental builders, who for the last several months have said that without 421a, they will have no choice but to build condos.

Some sponsors, however, say they can still make ground-up rental projects profitable without the tax cut.

“I think we’re in a fine position regardless, but it certainly does make you think twice,” said Alexander Brodsky of the family-run Brodsky Organization, which ranked No. 11 in terms of units owned.

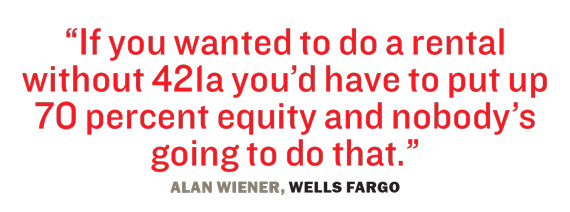

But Wells Fargo’s Wiener maintained that no one should expect to see substantial rental construction take place without the renewal of the tax program.

“If you wanted to do a rental without 421a you’d have to put up 70 percent equity and nobody’s going to do that,” he said, noting that anything entering the new development pipeline now without 421a is likely to be for-sale housing.

He added: “High land costs, high construction costs and very high real estate taxes, which impact renters, lead you to condos.”

—Additional research by Adam Pincus and Yoryi DeLaRosa