When Elena Smirnova jumped from Citi Habitats to upstart brokerage LG Fairmont in 2014, the firm started sending her leads it was buying from listings sites such as Trulia and Zillow.

Every month, Smirnova — then a newbie agent with just a year under her belt in the New York City residential brokerage business — was fed the names and phone numbers of potential clients who had plugged their personal information into one of those platforms. Then she’d cold-call each one.

While that might sound more like dead-end call center job than the glamorous life of a power broker, it paid off big-time last year when one of those leads turned into a $17 million contract for the penthouse at 25 Mercer Street in Soho.

It was a deal Smirnova said she could never have imagined doing on her own.

“Getting listings is incredibly competitive as a new agent,” said Smirnova, adding that she’s done about $39.4 million in sales over the past two years.

“When I was at Citi Habitats, I had to be in the office at 6 a.m. to get on a list to get assigned walk-ins,” she said. “I had to do all my own advertising. It was expensive, because I was competing with the other 30,000 agents in New York.”

LG Fairmont’s business model, however, provided her with an instantly fat Rolodex.

“This way is more effective,” Smirnova noted. “I automatically get 20 leads a month.”

And the seven-year-old LG Fairmont is not alone: It’s part of a new wave of start-up brokerages in New York that are building businesses by aggregating and handing off online leads.

Rather than shelling out millions of dollars a year on commissions and signing bonuses to recruit well-connected agents, companies such as LG Fairmont, TripleMint and Elegran Real Estate are buying leads all over the internet and creating technology that allows them to sort, track and deploy those leads en masse. Often the potential clients are farmed out to less-experienced agents.

These firms have become even more empowered since March, when listings platform StreetEasy launched its controversial Premier Agent feature in New York (see story). That program allows any agents to advertise right next to a property listing and collect all the leads it generates from users — even if it’s held by another broker.

While critics say the lead-generation model buoys underqualified agents into deals outside of their experience level, backers see it as a smart way to boost productivity.

“One of the first big premises of our entire company was that we could make everything more efficient if we focused on acquiring leads and had our agents focus of doing the best possible job of servicing them,” said David Walker, co-founder and CEO of TripleMint, which has raised $7 million in venture capital money since launching in 2011.

TripleMint’s COO, Philip Lang, left, and CEO, David Walker. The company has raised $7 million in venture-capital money since launching in 2011.

Already, TripleMint is marketing celebrity chef Bobby Flay’s $7 million Chelsea apartment, though ironically that listing did not come from an online lead.

Still, the model is not yet making a huge dent in the luxury market — LG Fairmont said most of its leads are in the $750,000-to-$2 million range and are on the buy side of the market — and Flay’s listing is a drop in the bucket in New York’s residential market. But backers say these firms have the potential to move into the luxury game in a very real way in the future.

“The larger we get, the more it’ll mimic the overall market,” Aaron Graf, a co-founding partner of LG Fairmont.

“When we get to scale, we should be more profitable than a traditional firm,” added Graf, making a bold prediction.

Still, these companies are betting that it ultimately pays more to go after buyers than to pursue star brokers — or to try to compete on collecting listings.

More established agents are less sure and seem unfazed by the prospect of losing business to these outfits.

Nest Seekers International broker Ryan Serhant — one of New York City’s top agents (see story on page 58) — said there will always be firms trying to ride the coattails of other people’s listings.

“You’re always going to have firms like that,” he said, adding that he’d rather see competitors buy advertising on StreetEasy and other sites than post his listings on Craigslist to drum up possible buyers.

“My priority is focusing on listings,” he said. “Through listings, you get buyers. That’s what makes the world go ’round.”

Challenging the stars

While the word “referral” might be overused in the brokerage business, nearly every top agent says connections are what help them land deals.

But for new agents — especially those who don’t run in the same wealthy circles that many elite agents do — those personal leads are often a pipe dream.

“I look at starting agents and say, ‘How do they get their foot in the door when there are so few transactions a year?’” said Leonard Steinberg, president of venture capital-backed brokerage Compass, which has aggressively recruited top agents with fat signing bonuses and other perks.

Steinberg, who was lured away from Douglas Elliman several years ago with an equity stake in Compass, said there’s nothing wrong with connecting buyers to agents — so long as the agent is qualified and it’s clear who the listing broker is.

In many ways, upstarts like LG Fairmont and TripleMint are the anti-Compass.

While Compass is rolling out technology to help star agents serve their existing high-profile clientele, these firms are forking over leads they’re hoping their agents will turn into clients.

And they are reimagining how marketing dollars should be spent, often taking decision-making power away from agents and putting it back in the hands of firms.

“It’s a question of whether you want to push money to agent marketing budgets or keep it as a corporate budget,” said Philip Lang, one of TripleMint’s other founders and the firm’s chief operating officer. “Traditionally, marketing dollars have been somewhat decentralized. We’re the opposite end of that, in that we decide what we think is best.”

While some individual brokers at New York’s most established firms — such as Elliman and the Corcoran Group — buy online leads on their own, so far none of the big brokerages have paid to pull in leads in great volume.

Meanwhile, some critics say the model is sleazy because it allows agents to feed off other brokers’ clients by masquerading as the primary contact on someone else’s listing.

“[Agents] feel like people are squatting on their listings,” Corcoran CEO Pam Liebman said last month during TRD’s annual Showcase & Forum.

Town Residential CEO Andrew Heiberger agreed.

“The problem is that it’s essentially a matching service for strangers,” he said. “About 80 percent of our deals are from referrals. And the closing rates for referred business are much higher than from advertising leads.”

In addition, competitors have pointed out the inherent risks of the lead-generation approach, noting that firms must pay for these contacts with no guarantees that deals will follow.

“With leads in general, you have to kiss a lot of frogs,” said Clelia Peters, president of Warburg Realty and a co-founder of the Manhattan-based MetaProp, which mentors real estate technology startups.

In addition, sources say that if more firms start buying leads, costs could skyrocket and hit these companies hard.

In addition, sources say that if more firms start buying leads, costs could skyrocket and hit these companies hard.

Still, none of these concerns seem to be stopping the momentum of these firms.

This year, shortly after Premier Agent launched, LG Fairmont fired off text messages to scores of agents at rival firms, touting an overabundance of business and offering recruits 70 rental and 30 sales leads a month.

“We have more business than we can handle,” one mass text read.

“Real estate has a 90 percent failure rate. It’s really hard to network your way to survival,” LG Fairmont’s Graf said. “How many cocktail parties can you have? It’s not enough to just know a few people in finance.”

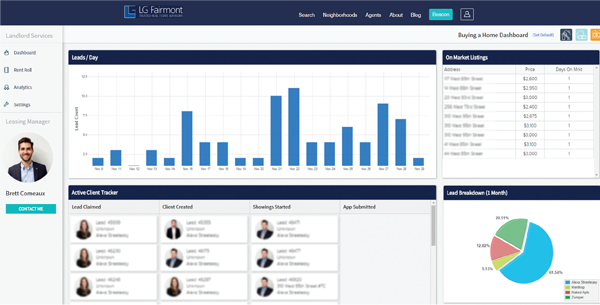

Graf argued that LG Fairmont’s value proposition is its software, which allows it to track leads and determine how many more to buy (or not to buy).

“If you just hand leads out on notecards, you’re not going to see a return,” he said. “You won’t get your money back.”

How it works

On a basic level, firms pay to get their contact information featured next to a listing on sites like StreetEasy, Zillow, Trulia and others.

Then, when a potential buyer inquires about a listing, the inquiry is automatically directed to the featured firm or agent.

Some of these websites charge on a sliding scale, meaning the leads for the most in-demand and pricey neighborhoods are the most expensive. On Realtor.com, the agent’s name and contact information are listed next to the listing; the agent and firm have the option to purchase email leads for that property.

On StreetEasy’s back end, brokers can see a real-time “leaderboard” that displays who’s advertising the most in a given ZIP code. The higher an agent’s position, the more leads that agent gets from the site.

And these firms are not just relying on third-party platforms. Some are investing in their own lead-generation models.

TripleMint, for example, is pouring millions of dollars into software designed to predict who is most likely to buy and sell real estate based on factors like when the owners purchased the property and how many kids they have, and then convert those people to clients by targeting them on social media or with cold calls.

TripleMint’s Walker said his team was “shocked” by how well these predictions work. He also brushed off concerns that the practice may be viewed as creepy.

“They’re going to forget how you got their numbers or email addresses, because you’re offering them something they want,” he said. “It’s about finding the people who are going to pick up the phone and say, ‘Whoa, thanks for letting me know about this.’”

What happens once the lead gets picked up depends on the firm.

LG Fairmont’s Aaron Graf, Philip Yellen and Brett Comeaux

At LG Fairmont, leads are assigned directly to agents based on an algorithm that factors in the languages they speak, past deals and neighborhood expertise. And agents are rewarded for closing higher-priced deals.

“You start out on rentals,” Graf said. “As you do better, the system ratchets you up. People know why they’re getting the leads they’re getting and how to move up.”

TripleMint has a different system. It employs centralized teams to vet leads by talking to prospective clients and sussing out how serious they are before farming them out to agents.

“At the point when the client is ready to begin the process of that transaction, that’s when we loop in the agent,” Walker said.

Meanwhile, CityRealty, which launched in 1994, has been offering a twist on the lead-generation model since 2001.

The company collects buyer leads through its website, vets them and then pairs them with brokers at firms across the city. CityRealty — which works with 800 New York City agents — takes a standard referral fee if a deal closes.

“We act as an extension of the agent’s team,” the company’s founder and president, Dan Levy, said. “As the agent is out there doing deals and showing properties, our team is effectively looking for new buyers for that agent.”

While CityRealty isn’t paying for leads from third-party sources, it is now competing in the lead-generation space — a fact Levy said he is not bothered by.

“With respect to some of the newer brokerage firms, I think more power to ’em,’” he said. “I can’t speak to the economics of paying up front for leads of an unknown quality — it might be great, it might be terrible. But I think broadly speaking, the idea of people trying new ways to engage with consumers [is a good thing].”

Those investing in this sector say the leads they are buying are worth it.

A screenshot of LG Fairmont’s lead-generation software, which the company uses to track agents and potential clients.

Elegran CEO Michael Rossi told TRD that 35 to 40 percent of the brokerage’s transactions come from online leads, with newer agents relying most heavily on the assistance. “It’s like giving a baby food from a blender before it can eat solid food,” he said.

TripleMint, meanwhile, said more than half of its deals come from its lead-generation system, while LG Fairmont said its software accounted for 70 percent of its deals. It claims to have closed 150 sales deals and between 500 and 600 rentals last year.

The firms using this model also keep a greater cut of the commission if a deal pans out.

LG Fairmont pays agents 50 percent commissions on deals that started as leads, and a more typical 60 to 70 percent split for deals those agents reel in on their own.

Still, some say the volume of potential deals that these firms provide can serve as a valuable recruitment tool.

Ed Longley, an LG Fairmont broker who previously worked at Halstead Property and City Connections, said it helps support agents during dips in business.

“I’m a very successful broker, no doubt about it, but you still have lulls,” he said. “I had one year where I made several hundred thousand in commissions, but the next year I went nine months without a paycheck because I sold five new developments that wouldn’t close until the following year.

“Having a constant stream of new clients is totally invaluable,” Longley added.

Meanwhile, developers are also leveraging the lead-generation model to target rental tenants.

Maiden+John — an offshoot of the public relations firm BerlinRosen — is working with Greenland Forest City Partners at 550 Vanderbilt in Brooklyn and Macklowe Properties at One Wall Street.

And this year, when marketing a New York office building geared to tech tenants, the firm pushed out social media ads targeted at the IP address of a hotel in San Francisco where top tech executives were attending a conference, according to Josh Cook, a director at Maiden+John.

Cook —who worked in political strategy on Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign — said the firm can also help developers figure out which price points to plug, renderings to display and taglines to use for projects based on what generates the most online traction.

“With this kind of microtargeting, we can see who’s clicking and then double down on that audience,” he said.

A risky bet?

While the lead-generation model can save a firm on commissions, it isn’t cheap.

Rossi said Elegran has spent between $2 million and $3 million over the past three years to build and manage its technology.

And though LG Fairmont would not disclose how much it paid for its lead-generation platform, it claims to be Zillow’s largest advertiser. The firm gets 5,000 leads a month from various sites, and with its 200 agents it’s currently breaking even, Graf said.

“It’s scary” he conceded. “You’ve gotta be kind of crazy.”

“It’s scary” he conceded. “You’ve gotta be kind of crazy.”

“The more agents you add, the more money you make,” he said.

That’s if the cost of buying those leads doesn’t spike.

Jordan Sachs, CEO of the residential brokerage Bold New York, said his firm tried buying third-party leads but determined that it didn’t make sense.

“We quickly realized that the cost per acquisition got to be very expensive for leads that weren’t great,” he said.

Mdrn.’s CEO Zach Ehrlich echoed that point. “At some point, Premier Agent and any legitimate third-party lead-gen program is going to reach pricing that may not be sustainable or feasible given revenue generated from commissions,” he said.

Yet some see the sector as one worth betting on and believe these firms have the potential to be Uber-style disruptors.

TripleMint is not the only one with sophisticated investors. LG Fairmont has gotten cash infusions from New York real estate investor Joseph Jemal, among others.

Meanwhile, Ben Rubenstein, CEO of Austin-based Opcity, a lead-generation firm that raised $27 million in series A funding last month, is considering expanding into New York.

But in addition to the cost of leads, firms have other risk factors to consider, including the threat of more companies eating into their fledgling businesses. That includes Zillow rival Realtor.com, which is owned by News Corp. subsidiary Move Inc.

Four years ago, Move bought a lead-management tool called FiveStreet that lets agents track and respond to leads in real time.

In April, it licensed a customized version of FiveStreet to Terra Holdings, which owns Brown Harris Stevens and Halstead.

While neither firm buys leads in bulk, Jim Cahill, Terra’s chief information and technology officer, said the number of leads coming in from listing aggregators has been growing “exponentially,” because agents are purchasing them on their own.

“None of this takes the place of an agent, but it’s a tool to help them,” Cahill said. “If an agent waits a day to respond, the lead is gone. You either have a team of six assistants just on your email or you have a tool that can help you manage it.”

Still, some think these firms will have trouble truly cracking the high-end market.

“Buyers over $5 million might start their search and do their research online, but when they find something they’ll call the broker they already know,” Heiberger said.

Maelle Gavet, COO of Compass, put it this way: “The models might start to converge at some point, but the agent will always be at the core of what real estate is all about.”