When Madison Realty Capital [TRDataCustom] bought the debt on a senior assisted-living facility in Park Slope late last year, the property at 1 Prospect Park West was steeped in controversy.

The owner, Haysha Deitsch, had become entangled in a legal dispute with the tenants’ families, who alleged he illegally tried to evict residents as part of an attempt to sell the building. On top of that, Sugar Hill Capital Partners, which had agreed to buy the property for $76.5 million in 2014, sued Deitsch over the delayed eviction process.

Now Madison, which filed foreclosure proceedings on the 139-bed facility this April, is waiting for the dust to settle in order to receive the remaining payments on the $33.4 million in debt it acquired or take further action.

If the building’s sale does not go through as planned, Madison — a hybrid investor and lender — will likely hold a foreclosure sale, said Joshua Stein, an independent real estate attorney based in New York. Such proceedings typically result in a foreclosure by the lender, though anyone can bid, Stein noted, calling the process “a whole little dance.”

“The very common result is that the lender would ultimately take it over,” he said.

The hairy predicament is one of many for the Manhattan-based firm, which frequently steps in to finance properties and developments that are on the brink of bankruptcy or struggling for other reasons. At the same time, Madison has become a recognizable name among the city’s often shadowy hard-money lenders by providing much needed loans to middle-market investors and developers who may struggle to find them elsewhere.

And as traditional bank financing for New York City construction projects and acquisitions continues to cool, the firm’s lending operation is gaining steam. Since opening for business 12 years ago, Madison has provided $3.5 billion in debt and invested close to $2 billion in equity in more than 460 deals. In 2015 alone, the firm, led by Josh Zegen and Brian Shatz, closed $750 million in mortgages. In an interview at his office last month, Zegen told The Real Deal that he expects to lend $1.1 billion this year, which would mean a 46.7 percent year-over-year increase.

Likewise, Madison has also become more aggressive with its foreclosure and legal activity as some borrowers, like Deitsch — who defaulted on a $3.4 million settlement to the five remaining residents at 1 Prospect Park West — have been unable to pay off their debt.

One commercial lending executive at a major New York bank said, “Madison plays in an edgy class of lending,” one that correlates with “weaker sponsors who are seeking higher leverage.”

TRD found that limited liability companies affiliated with Madison filed at least 50 foreclosure proceedings on more than 70 New York City properties since 2012. Nearly half of the proceedings were filed between January 2015 and August 2016. And the two most recurring borrowers in those cases are notorious figures — Evgeny “Gene” Freidman, known as the Taxi King, and the litigious Hasidic real estate investor Chaim Miller.

The vast majority of the foreclosures are on distressed debt that Madison purchased rather than originated, according to the firm. Yet, the financial instabilities of the borrowers at the other end show the calculated risks that Zegen and his associates take in their dual lender-investor roles.

The vast majority of the foreclosures are on distressed debt that Madison purchased rather than originated, according to the firm. Yet, the financial instabilities of the borrowers at the other end show the calculated risks that Zegen and his associates take in their dual lender-investor roles.

At least four borrowers have sued Madison over its debt practices since 2009, court records show. In the past year, Brooklyn-based SMK Property Management accused the firm of predatory lending over seven defaulted mortgages on multiple Greenpoint properties in a $150 million suit, while Queens investor Global Universal Group alleged Madison fraudulently refused to close a loan on a Flushing building and instead foreclosed on the property. Both lawsuits are ongoing.

“They look like sweethearts, but they can be vultures like other hard-money lenders,” said one investment sales broker who has arranged deals in which Madison was involved.

Starting from scratch

Zegen, 41, started his real estate career in his late 20s brokering small bridge loans for mom-and-pop investors in Brooklyn while working at Alpine Commercial Capital, a boutique firm he co-founded. Then, at age 30, he teamed up with Brian Shatz — his college roommate at Brandeis University — to form Madison Realty Capital in 2004.

Through Shatz’s family connections, the two raised $10 million, which went to the company’s first institutional fund. Just six months later, the real estate investment trust Capital Source provided Madison with a $45 million line of credit, which the firm tapped for its debt originations.

Then in 2009, Zegen partnered with industry player Martin Nussbaum to form a wholly owned subsidiary of Madison called Silverstone Property Group. The company focused on acquiring distressed assets amid the downturn. Four years later, Nussbaum left Silverstone to become a founding partner of the New York development and investment firm Slate Property Group, and Silverstone became a property management affiliate of Madison.

Zegen’s entrepreneurial spirit dates back to his childhood. He bought baseball cards wholesale from manufacturers and sold them in his neighborhood in Glen Rock, New Jersey, at the age of 10, he said. He and Shatz later ran a hat business in college, selling old, once-damaged hats they bought and refurbished.

“There was always something I was selling,” said Zegen, now a husband and father of two young children.

Today, about 60 people work at Madison’s single office in Midtown East, with half of them focusing on the debt side of the business. Among those employees is industry veteran Michael Stoler, who has helped connect Zegen and Shatz with high-profile borrowers and key banking contacts. Stoler declined to comment for this story.

Marc, one of Zegen’s two younger brothers, works at the firm as a vice president of acquisitions and debt originations. (Their other brother, Michael, is an actor who has appeared on HBO’s “Girls” and “Boardwalk Empire.”)

Most of the debt that Madison originates is in the $30 to $100 million range. And virtually all of the loans are first mortgages, which means they take priority over all other liens on a property if the asset were to fall into foreclosure.

“We classify our debt investing business as ‘special situation,’” said Zegen. “Whether it’s time-sensitive, a partner buyout or a recapitalization.”

The Rheingold Brewery redevelopment

Over the years, Madison has rolled out a series of debt funds — in 2005, 2012 and most recently this past May — each one bigger than the last. The third debt fund raised $695 million, and Zegen said the fourth, which is slated to launch in the next 12 months, will likely be the firm’s largest one yet. Madison also has an equity fund, which it launched in January.

The debt and equity funds’ investors are decidedly institutional — public and corporate pension funds, asset managers and foundations and endowments — according to Zegen.

But despite the firm’s ties to major developments and acquisitions, many in the industry still categorize Madison as an alternative to institutional financing. Zegen noted that his borrowers are “not the typical institutional sponsor” type and may lack liquidity, though the real estate they seek to acquire is typically of an institutional caliber.

Whereas most banks rely on sponsor relationships, Madison is decidedly “sponsorship agnostic,” said Aaron Appel, a managing director in JLL’s real estate investment banking division, who has worked with the firm on deals.

One for the books

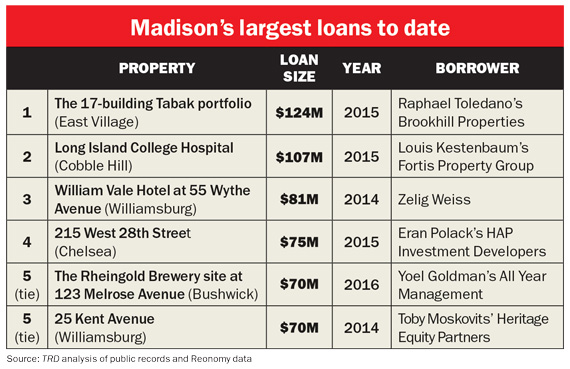

Madison turned heads last year when it provided a whopping $124 million loan to controversial 26-year-old multifamily investor Raphael Toledano for his purchase of the 17-building, $97 million Tabak portfolio in the East Village.

Toledano, a former broker, not only lacked a track record as a landlord but he also had ties to a fake law firm and had been convicted of aggravated assault. The sponsor, however, passed Madison’s “smell test,” according to a source familiar with the matter. That deal remains the largest loan the firm has ever provided.

Zegen declined to comment on the Toledano transaction. But the source said Madison was impressed that Toledano bought the package at a roughly 30 percent discount to its actual value and that he had received multiple loans from such New York banks as Signature Bank in the past — albeit each comparatively smaller than the one Zegen’s firm was providing.

That transaction raises the question of who the firm will not loan to. Zegen said he avoids sponsors with ties to alleged fraud and ones looking to acquire a property with a bad basis.

“The big mistake I’ve seen over cycles with a lot of lenders is they get enamored by borrowers,” Zegen said. “You’re taking on a lot more execution risk and therefore not being paid for the risk you’re taking.”

Madison has a stable of repeat borrowers, including Yoel Goldman’s All Year Management, David Marx’s Marx Development Group and even some who have had a property taken over by the firm in the past, Zegen said.

In April, Goldman needed to score a $70 million acquisition loan for his 1 million-square-foot Rheingold Brewery project in Bushwick in a very short time frame. Although a competing lender was cheaper, Goldman went with Madison because the firm had provided him with several loans in the past, according to Zegen and a representative for the borrower.

“If he didn’t meet [the deadline for closing the loan] that day, he literally had a seller that was going to try to take his deposit,” said Zegen. “He had a lot of money up — a lot to lose. And there was a lender providing a term sheet at 1 to 1.5 percent cheaper than our potential loan.”

A spokesperson for Goldman told TRD: “Madison has deep pockets. They know how to make a lot of money, but they are also creative in that they help the borrower make a great deal as well.”

Both borrowers and mortgage brokers who have worked with Madison credit the firm for its speed and reliability. Zegen said the average debt deal closes in about three weeks, sometimes as quickly as in a matter of days.

Both borrowers and mortgage brokers who have worked with Madison credit the firm for its speed and reliability. Zegen said the average debt deal closes in about three weeks, sometimes as quickly as in a matter of days.

“Situations arise where someone’s under contract and a lender backs out of a deal and they need to move very quickly,” Appel said. “Madison can serve as a [backup] lender there.”

League of their own

The firm’s interest rates, which average between 9 and 12 percent (significantly higher than bank loans, which now average 3 to 5 percent), are often on par with other hard-money lenders, sources told TRD. In some cases, Madison has gone as high as 2 percentage points above a direct, non-bank competitor.

Other active firms commonly identified as hard-money lenders in New York City include G4 Capital Partners, Emerald Creek Capital, Hudson Realty Capital and Titan Capital. Madison, however, is a special case because it’s one of a select group of owner-operators that can provide added insight as a sponsor and fine-tune the underwriting accordingly, according to several industry players.

Ackman-Ziff Real Estate’s David Harte, who advised on Madison’s $107.3 million financing for Fortis Property Group’s purchase of the embattled Long Island College Hospital in Cobble Hill, said the firm was key in navigating the initial hurdles in the deal. The site is one of the few in the neighborhood with as-of-right development potential.

Still, much like the assisted-living facility at 1 Prospect Park West, the property is in the throes of controversy.

The U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York is investigating the role Mayor de Blasio had in the sale of the troubled hospital site to Fortis Property Group for $240 million in 2014. Residents had pushed to save the debt-ridden hospital and have continued to oppose the site’s redevelopment as luxury condos. Fortis is now weighing whether to persuade City Council member Brad Lander to back a rezoning that would allow for 900,000 square feet of housing — or proceed with building the as-of-right 529,000 square feet of housing.

Madison’s investing business carries its own weight. The firm now owns 43 buildings with a combined value of $2 billion, Zegen noted, and has been active across several asset types, from multifamily to office properties. The industrial Brooklyn Whale building on the Sunset Park waterfront, which the firm bought for $82.5 million last year, is being repositioned as a 500,000-square-foot destination for tech and creative tenants.

In one of the firm’s largest purchases yet, it partnered with USAA Real Estate Co., an arm of insurance giant USAA, to buy the Buchanan, a 16-story Midtown East rental building, for $270 million all-cash last year.

Yet, Madison’s dual lending and investing model is becoming less unique. A growing number of developers — including Kushner Companies, Moinian Group and RXR Realty — are also breaking into the peer-to-peer lending game and making relatively high returns on their loans.

Other dominant lender-investors in the city include Square Mile Capital Management and Ari Shalam’s RWN Real Estate Partners, the family office of Apollo Global Management co-founder Marc Rowan.

Still, the retreat of banks and other traditional lenders from the commercial real estate business has created a huge advantage for Madison in recent years. While bank lending regulations have resulted in increasingly steep requirements for cash equity in a deal, the rules Madison plays by are far less demanding.

“More and more, we see the need for our kind of capital,” Zegen said. “A lot of lenders out there have pulled back because that A-piece they expected to come in with higher proceeds is not.”

An industry divided

The term “hard-money lender” is indeed divisive. And lawyer Ed Mermelstein of Rheem, Bell & Mermelstein said Madison is by far the most aggressive of such alternative lenders in New York.

“Their business model, which allows for ownership on the possibility of a default, is not for the faint of heart,” Mermelstein said, noting that “they’re not predatory so much as opportunistic.”

3 Sutton Street

Zegen said he doesn’t care for the label “hard-money lender” in general, noting that it reminds him of the term “junk bonds” born out of the 1980s.

But despite the appeal of a non-bank lender for an investor seeking financing under tight circumstances, such deals come with a higher likelihood of predatory or “loan-to-own” behavior, according to industry sources. Lenders accused of engaging in such transactions swiftly deny it, but examples in the New York real estate industry remain prevalent.

In SMK’s suit, the plaintiff claims that it seemed “odd that a lender/investor who had purchased such distressed/defaulted mortgage notes and obviously knew about the plaintiff’s ‘borrower’s’ history of default would agree to fund a multimillion dollar loan.” (New York Community Bank provided the original loans to SMK and later sold them to Madison, according to the lawsuit.)

Zegen, who maintains that SMK owes his firm $15 million in debt payments, told TRD that Madison does not engage in predatory or loan-to-own transactions.

“We make a loan looking to get paid back,” he said. “That doesn’t mean that if a borrower doesn’t pay and there’s no workout plan, we won’t exercise our rights and remedies. Whether you’re Blackstone or a bank, you have to have a means to get your capital back.”

Over the past seven years, there have been three other lawsuits against Madison, including one from an artist over a property in Clinton Hill in 2009 and another concerning a 12-acre plot of land in Houston, Texas, in 2013. Those cases have since been dismissed.

In response to the bevy of foreclosure cases Madison has taken on, Zegen said more than 90 percent of those proceedings have been for relatively small loans provided by local savings banks that sold the mortgages to clean up their balance sheets. And while there is far less distressed debt to buy than there was in 2012, Madison continues to seek out those deals because of “outsized returns,” Zegen said.

Buying distressed debt is not necessarily a bad thing, said real estate attorney Stephen Meister of Meister, Seelig & Fein.

“If the borrower has cut a deal with the original lender for relief, and the loan is traded before that deal is memorialized, that works as an injustice to the borrower,” Meister noted. “Otherwise, buying distressed debt and starting a foreclosure action is lawful. It creates liquidity in the capital markets, and the foreclosure would likely happen no matter who owns the debt.”

Several brokers and borrowers said Madison does not intend to take over properties through its debt platform, but rather get repaid on its loans, make returns for its investors and recycle the capital for future transactions.

“Most hard-money lenders don’t want to take over a loan because it’s just a headache,” said Robert Gordon of the New York investment and brokerage firm Rushmore Capital Partners, which has arranged loans provided by Madison.

All obstacles, controversies and risks accounted for, Zegen said he’s confident the company’s growth and success have made them worthwhile.

“People make mistakes, and I’m not saying we’ve never made mistakes,” he acknowledged, “but we were able to be a fiduciary to our investors and provide great returns.”

“As a firm, we’ve grown for a reason,” Zegen added. “You can’t be a bad counterparty, have a bad reputation and grow the way we have.”