Trending

Who earned and who got burned?

A deep dive into Manhattan’s luxury resales, including which business moguls and celebs made out big in the last decade —</br> and who stomached

When Jets owner Woody Johnson accepted a $77.5 million offer for his Upper East Side apartment in October 2014, he hit on a euphoric moment in the New York City real estate market. The Johnson & Johnson heir’s apartment at 834 Fifth Avenue was one of three sales that broke the co-op price record that year.

Just three years later, however, his sister Libet’s estate is trying to sell her Upper East Side townhouse and contending with a much different market.

Following the socialite’s June death, her estate slashed the price of the property to $45 million — despite the fact that she paid $3 million more than that in 2011 and that the 12,000-square-foot home was initially listed in 2016 for $55 million.

The very different trajectories of those two listings offer a window into Manhattan’s luxury market — reflecting the seismic shift the sector has experienced in the past few years. The listings also speak to the art of timing the market: Real estate fortunes have been made — and lost — by speculators trying to predict the very moment the market will turn.

And this past cycle was no exception, as some savvy investors paid pennies on the dollar for valuable properties while others stomached ugly losses.

“Timing is real estate’s best friend and worst enemy,” said Compass President Leonard Steinberg.

This month, as the market slide continues, The Real Deal traced the arc of the Manhattan luxury market, analyzing nearly 900 resale transactions between January 2007 and June 2017.

TRD zeroed in on condos south of 96th Street that sold and then resold for $4 million or higher to pinpoint the best times to buy and sell during that decade-long stretch — and to determine who timed the market best and who got burned.

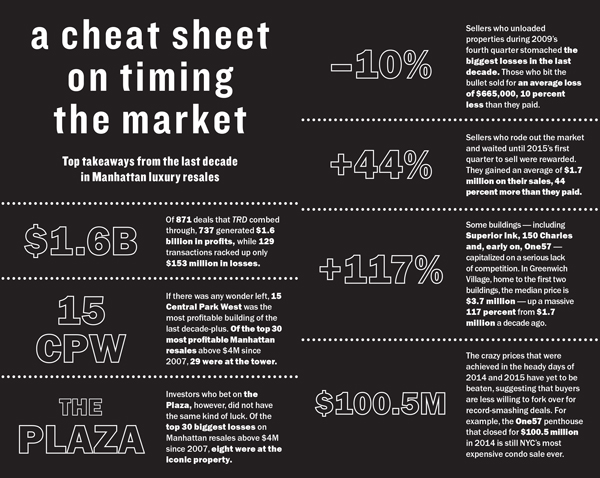

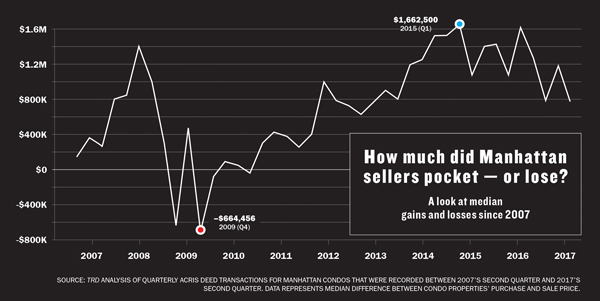

What we discovered was that the absolute best time to sell (and worst time to buy) was 2015’s first quarter — when prices were peaking. Of the 44 deals that closed during that period, owners sold for an average gain of $1.7 million, or about 44 percent more than they paid.

On the flip side, the worst time to sell (and best time to buy) was 2009’s fourth quarter — when prices had bottomed out. Of the 61 deals that closed during that period, owners sold for an average loss of roughly $665,000, or about 10 percent less than they paid.

TRD also learned that some buildings (like 15 Central Park West) held their value well, giving buyers millions of dollars of upside. Others (like the Plaza), however, often drained investors’ bank accounts.

Not surprisingly, high-profile players — from business titans to Hollywood celebrities — ended up in both the black and the red.

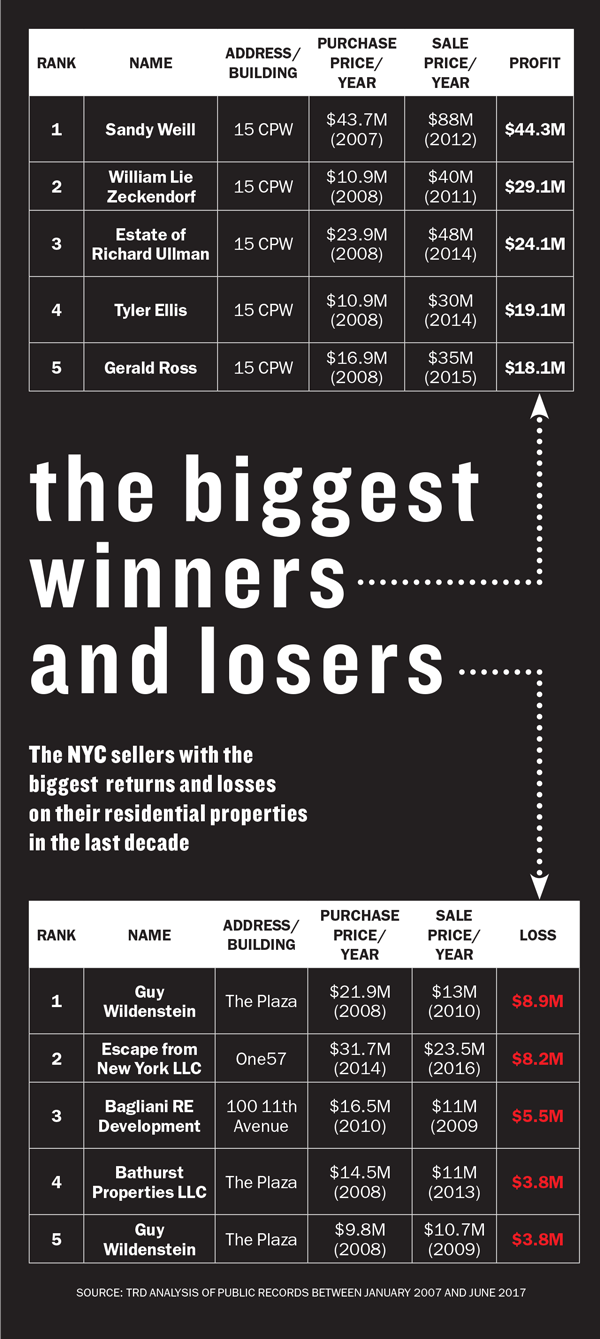

Former Citigroup Chairman Sandy Weill was one of those who made out like a bandit. He didn’t just make headlines with his record-breaking $88 million 15 CPW penthouse sale in 2013; he also pocketed more cold, hard cash than any other Manhattan seller in the last decade.

But actor Leonardo DiCaprio and comedian Mike Myers, along with billionaire art dealer Guy Wildenstein, were among the large group of sellers who lost money.

Market analyst Jonathan Miller, president of real estate appraisal firm Miller Samuel, said that at the market’s pinnacle, investors viewed real estate transactions in the same way they thought about stocks.

“Real estate was perceived as a highly liquid asset — something you could jump in and out of and make money,” Miller said.

That was, and still is, especially true among the 1 percent who — unlike New Yorkers in the sub-$1 million market — often purchase a condo only to turn around and sell it a few years later.

Interestingly, the vast majority of resales over the past decade were profitable for investors. Of the 871 deals that TRD analyzed, 737 generated $1.6 billion in profits for buyers. While investors only lost a combined $153 million on 129 deals, those losses undoubtedly stung. (Four investors broke even.)

Not surprisingly, Manhattan’s biggest gains and losses have been in the new-development sector, which has seen a major run-up in prices since the last recession.

“The thought process for new development has been this idea that when you buy in, you’re in the money,” said Adam Modlin, one of the brokers tapped to market the Getty, a planned condo designed by Peter Marino near the High Line. “By the time you close, [the property] appreciates.”

But in many ways, the buyers who fueled the frenzy by paying record-setting prices may now have the most to lose.

“Prices have escalated to the point where by the time you buy in, you’re buying in at premium value,” Modlin said. “There’s no positive outlook for immediate appreciation.”

The casualties

As Sir Isaac Newton famously said, “What goes up must come down.” But for several years, that adage didn’t seem to apply to New York real estate.

In 2014, for example, sellers were raking it in, and even though the market was only a few years past the worst downturn since the Great Depression, Manhattan buyers didn’t seem worried that conditions would sour again.

In the fourth quarter of that year, the median price for a Manhattan condo had shot up by nearly 15 percent from just a year earlier. Buyers seemed almost intoxicated with the luxury market, willing to pay outrageous asking prices with the assumption that they would be able to sell for even more.

That phenomenon lasted well into 2015, when a string of monstrous residential deals began piling up and making headlines.

In March, billionaire Len Blavatnik broke New York’s priciest co-op record when he forked over $77.5 million for Johnson’s duplex. The next month, hedge fund mogul Bill Ackman and a group of his buddies pooled together an astounding $91.5 million for an investment apartment at One57 in the priciest sale of the year. And two months later, in June, Russian financier Andrey Vavilov sold a full-floor penthouse at the Time Warner Center for $51 million to an anonymous buyer after paying $37.5 million for it in 2009.

But now, just two years later, many of the buyers who shelled out during those frenzied days are facing headwinds.

For the time being, the buyers of those three apartments are hanging tight, perhaps avoiding selling into a soft market and waiting for the right time to flip. “Myself and a couple of very good friends bought into this idea that someday, someone will really want it and they’ll let me know,” Ackman told the New York Times in 2014.

That day is clearly not now. In all, industry insiders say the market shift — median prices took an about-face and dropped 3.3 percent in this year’s first quarter, year over year — was inevitable.

“For a while, if you bought something, you could turn around in two years and absolutely make money on it,” said Shaun Osher, CEO of the Manhattan boutique brokerage CORE. “That [was] a guarantee for the last eight years, but that’s not a normal market. The days of getting a 30 to 50 percent appreciation year over year … are gone. Those days should never go on forever — that’s how you get into trouble.”

A large part of the problem for sellers today is the flood of new inventory.

Egged on by the strong post-recession recovery, developers began feverishly building condos all over Manhattan.

In 2013, for instance, 2,384 Manhattan condos came to market — just seven units shy of the total from the three previous years combined, according to figures compiled by Corcoran Sunshine Marketing Group.

Douglas Elliman broker Jacky Teplitzky said this “new generation of buildings is having a tougher time.”

“Whatever was finished in 2015 and 2016, people thought they could flip and make a lot of money,” said Teplitzky, who’s brokered deals at some of New York’s priciest condo towers. “We’re not seeing that now. Once upon a time, when a high-end building was being built, you only had that one tower. Now, there are a lot more options for buyers in that very, very high price range.”

§

For some who’ve opted to sell, the results have been grim — particularly in buildings that debuted at the top of the cycle.

Most famously, the art world’s Wildenstein — who was cleared of tax-fraud allegations this year by a French court — sold his Plaza unit for $13 million in 2010. That was about 40 percent less than the $21.9 million he paid in 2008 and gave him the unlucky distinction of losing more money than any other investor in Manhattan in the last decade, according to TRD’s analysis. Wildenstein also sold another condo at the Plaza for a $3.8 million loss in 2009. Attempts to track down Wildenstein were unsuccessful.

An investor under the name “Escape from New York LLC,” who ate more than $8 million after selling his 62nd-floor pad at One57 for $23.5 million, lost the second most in Manhattan during that stretch.

Next up was Bagliani RE Development LLC, which is based in Italy. It bought a penthouse at the Jean Nouvel-designed 100 11th Avenue for $16.5 million in 2010 and sold it for $11 million in 2013 — taking a 33 percent haircut.

Financial losses have spanned the borough and have spared few. DiCaprio, for example, paid $10 million in 2014 for a unit in Delos at 66 East 11th Street — a green condo with “wellness” amenities like purified air, posture-supportive flooring and Vitamin C-infused showers — only to resell it for $8 million late last year.

Myers, of “Austin Powers” fame, meanwhile, sold at the Tribeca condo conversion 443 Greenwich Street for $14 million — $675,000 under what he paid less than a year earlier and a discount from his $15 million listing price. And at 150 Charles Street — the record-setting condo developed by the Witkoff Group in the West Village — the buyer of a maisonette swallowed a $400,000-plus loss on one of the first resales in January.

And the list goes on.

Two owners at One57 [TRDataCustom] — Nigerian oil magnate Kola Aluko and business executive Sheri Izadpanah — are facing foreclosure.

Even 15 CPW, the so-called Limestone Jesus, which has been largely immune from losses, hasn’t been unscathed. Late last year, an owner who bought a three-bedroom under the name Westside RE Properties LLC sold for $20.6 million, about $3 million less than the 2012 purchase price.

Compass’s Steinberg, who brokered the Charles Street deal, said while it may seem nonsensical for wealthy owners to sell for a loss, in some cases it makes more economic sense than holding on to a property.

“For every sale that happens where you can say, ‘Why did they sell?’ there’s a good reason for it,” he said. “It’s often not the property; it may be circumstance or timing.”

“When you pay an extreme price in an extreme market and you don’t hold on to that property for a long time, you can hit the market when it’s not extreme,” he said. “You have to be patient. For some people, taking a loss is better than having to pay debt service.”

In many cases, buyers who lost their shirts simply parked their money in the wrong building — at the wrong time.

TRD’s data dive found that in the last decade, owners at the Plaza lost more on their resales than at any other Manhattan building.

Buyers who shelled out for units in 2007 at the iconic property — which the Elad Group bought in 2004 and partially converted into condos and hotel-condos — paid an average of $3,554 per square foot, almost unheard of for Manhattan at that point. But sources said that the combination of a tough market and construction issues at the building hindered values there.

Of the 58 resales analyzed by TRD at the property, 30 investors lost a combined $50 million, or an average of $1.7 million each. Another 27 investors at the property turned a profit, generating $44 million. And one investor broke even.

Barring a few exceptions, buying in 2007 or early 2008 was the kiss of death for those who flipped properties.

“If you went into contract in that window, that was the epitome of bad timing,” said Miller. “It doesn’t get worse than that. But the mindset in 2007 wasn’t that there was a precipice we were about to jump over.”

Miller said investors trying to sell at the bottom of the market in 2008 and early 2009 — just after Lehman Brothers collapsed and financial panic set in — found themselves playing musical chairs with no seat in sight.

Contracts had plummeted 70 percent, and prices had dropped a massive 30 percent. “That was the nadir, it was the bottom,” he said.

TRD’s cover headlines during that time offer a window into the state of the market: “Breaking the Bull,” “Development in Distress,” “Condo Plans Collapse,” “Bring on the Bargains” and “Fighting Buyer Mutiny,” to name a few.

But when the stock market began its gradual recovery in mid-2009, savvy real estate investors began to move.

“The market flipped back on,” Miller said. “People were just waiting for a sign.”

The bandits

If the Plaza did a poor job of holding its value for investors, 15 CPW, which debuted around the same time, did the exact opposite.

Overall, owners at the building amassed profits far more often than their counterparts at any other Manhattan building over the last decade, TRD data show. In fact, the 29 most profitable resales of the last decade were at all at 15 CPW.

While Weill was the biggest winner, selling to Ekaterina Rybolovleva — the daughter of Russian business mogul Dmitry Rybolovlev — in 2012 for $44.3 million more than he paid in 2007, he wasn’t the only one who made out handsomely. Developer William Lie Zeckendorf, whose firm built the tower, took in the second most of any Manhattan seller during the 10-year stretch when he nearly quadrupled his money on his personal penthouse at the Robert A.M. Stern-designed tower.

He bought the unit for $10.9 million in 2008 and then flipped it for $40 million to Min Kao, co-founder of the tech company Garmin, in 2011.

The estate of pharmaceutical mogul Richard Ullman was next on the 15 CPW profit gravy train, making the third-highest overall return in Manhattan during the last decade. The condo sold for $48 million in 2014, making a massive $24.1 million on Ullman’s $23.9 million purchase in 2008. (However, the next owner, an LLC linked to a Thai company, took a $3 million loss on its 2015 sale.)

Casino mogul Richard Fields didn’t do too shabbily, either. In June 2008, he forked over $13.6 million for a 15 CPW unit. Six months later, he recouped his investment — and then some — when he sold the pad for $27 million, or almost double what he had just paid.

And Spanx founder Sara Blakely and her husband sold their 37th-floor 15 CPW property in mid-2014 — at the peak of the condo craze — for $30 million, 148 percent more than the $12.1 million they paid in 2008. That made the couple the sixth-biggest winners of the last decade.

Were these (a) smart investments, (b) lucky gambles, (c) impeccably timed deals or (d) all of the above? The correct answer: (d).

While the earliest buyers and the developers’ friends no doubt capitalized on “friends and family” prices, many were also savvy enough to ride out the market.

“They were less likely to sell when the market plummeted,” said Dan Levy, founder of CityRealty, which publishes market data.

But it wasn’t only 15 CPW sellers — or those at the tippy top of the luxury market — who timed the market flawlessly.

Across town, real estate scion Adam Rose, who heads Rose Associates with his cousin Amy, sold his penthouse at 240 Park Avenue South for $16 million in late 2014 — nearly $8 million more than he paid in 2008.

Rose — who characterized the price he got as “rather amazing” — said he sold because he wanted to live in Westchester full time. “I achieved that price because it was hugely custom work that was never intended to be sold,” he said. “No one should build at that level. Trust me.”

“By the way,” he added, “it was a two-bedroom apartment that I sold for $16 million. Pretty crazy!”

Some brokers pointed out that in addition to making a premium on their raw purchase prices, some foreign buyers are also benefiting from favorable exchange rates — even on lower-end, less-flashy deals.

Platinum Properties CEO Khashy Eyn, for example, said he worked with a European investor who bought a 15 William Street penthouse in the Financial District for $2.8 million in 2009 and sold for $4.5 million in 2016.

“The exchange on currency alone made them anywhere from 30 percent to 40 percent return on their money,” Eyn said.

§

On the new-development front, Extell Development’s Gary Barnett — who got a capital infusion from two Abu Dhabi-based investment funds for One57 in the depths of the recession — launched sales at the tower in 2011. While the atmosphere at One57 is far less ebullient today, that timing could not have been more ideal for the sponsors, who began selling just as buyers were jumping back into the market.

“They were lucky that the market cratered. Then they ended up first out of the ground. They were in position,” said Miller. “The reason why their sales took off initially was because they were the only game in town.”

Despite the poor timing, Related Companies’ Superior Ink — one of the first new condos in the West Village when it launched in 2009 — did well for the same reason. The building has seen average sale prices skyrocket to $4,858 per square foot over the past year alone. That’s up from $2,956 per foot in December 2012, according to CityRealty data.

“There was no real competition at the time [it launched],” said Elliman’s Leslie Wilson, who worked for Related back then. “We were on the river in the West Village. We knew people had a lot of money and they wanted services, and there were no buildings that really had that.”

The building was sold off of floorplans, and a number of buyers bought multiple units that they then combined.

One of the early buyers was Houston Rockets owner Leslie Alexander, who paid $25.5 million for a penthouse in 2009 — only to sell the unit a year later to the aptly named space tourist Mark Shuttleworth for $31.5 million. Alexander, who never lived there, walked away with $6 million.

More recently, in July 2016, high-profile Connecticut attorney James Early sold his penthouse in the building for $9.5 million to Jordan Roth — the son of Vornado CEO Steven Roth and the owner of an adjacent unit. That price more than doubled the $4.3 million Early paid in 2009.

Superior Ink was one of several new condos that helped shape that Far West Side area and drive up prices.

Compass’s Steinberg bet early on the neighborhood, shelling out $1.2 million for a two-bedroom at 251 West 19th Street in 2005. In 2010, with the market still depressed, he doubled down on the neighborhood, paying $2.75 million for a unit at the Annabelle Selldorf-designed 200 11th Avenue.

“Everyone was like, ‘Oh my God, you’re crazy,’” he recalled. “I admit I was very scared.”

But in 2013, he sold the first unit for $2.75 million, and he said he thinks the second is worth $5 million. He has it rented after listing it last year for $13,000 a month.

The wannabes

Despite market fluctuations, the enormous overall gains in the luxury market during this cycle — prices are up 76.8 percent since 2006 — have given sellers license to at least attempt to score astronomical prices.

In May, Grammy Award-winning musician Sting and his wife, Trudie Styler, listed their 15 CPW duplex penthouse for $56 million — more than double the $27 million they paid in 2008.

Meanwhile, Claude Wasserstein — the third wife of late financier Bruce Wasserstein — has her Upper East Side penthouse on the market for $65 million — $30 million-plus more than she paid in 2008.

And nearby, Somerset Partners’ Keith Rubenstein, who paid a mere $35 million for his Upper East Side mansion in 2007, now wants $85 million for the 15,000-square-foot house following a gut renovation (Hermès leather walls included).

But as the market has shifted into neutral, Manhattan luxury sellers have made a sport of chopping listing prices.

Upon being named U.S. Secretary of Commerce, billionaire Wilbur Ross listed his penthouse at 171 West 57th Street for $21 million, after paying $18 million in 2007. But in March, Ross slashed the price to $16.5 million. The unit is still on the market.

And direct-marketing mogul Cheryl Mercuris, who bought her Time Warner Center property for $11.1 million in 2008, cut her asking price for a sixth time in April, to $16 million. The unit was asking $50 million when it was first listed in 2013.

Owners at the building — where only four of the 24 resales surveyed by TRD sold at a loss in the last decade — are contending with an influx of new Billionaires’ Row inventory.

Icelandic investor Eyjólfur Gunnarsson appears to be even more desperate to unload his pad at 50 Gramercy Park North. Gunnarsson paid $22 million for the penthouse in 2007 and has chopped the price several times. Last month it stood at a puny $8.9 million.

Though it’s unclear why Gunnarsson is itching to sell (he didn’t return calls), brokers said sophisticated investors often view these deals as part of a broader “balance sheet,” meaning they’re willing to take a hit if they are making money on a deal elsewhere.

In addition, some developers have been discounting sponsor units and throwing in broker incentives (see related story on page 40).

And while investors may not be seeing the same returns they did five years ago, that doesn’t mean it’s a bad time to invest.

Osher said some investors have outsized and often unrealistic expectations. “We’ll go in to value an apartment and the sellers will say, ‘Oh, I’m only going to make $500,000?’ Like it’s bad news,” he said. “Since when did that become bad news? I have buyers pissed off right now because they can’t sell for a $1 million profit. That’s more than the average price of a home in the United States.”

—Research by Yoryi DeLaRosa