Douglas Eisenberg, New York City’s fifth-largest residential landlord, insists he is not the enemy — except maybe to his rivals on the tennis court.

When he takes out his Wilson Blade racket at Sportime Randall’s Island, the 20-court facility he’s a regular at, his opponents — often titans in the real estate industry — say they are up against a tactical competitor.

The Blackstone Group’s [TRDataCustom] Jonathan Gray, an occasional on-court rival, said while Eisenberg may seem “low-key,” he actually “dives for every ball.”

“He has just a quiet, understated tenacity,” said Gray, who has worked with Eisenberg on several deals. “He’s remarkably similar in business.”

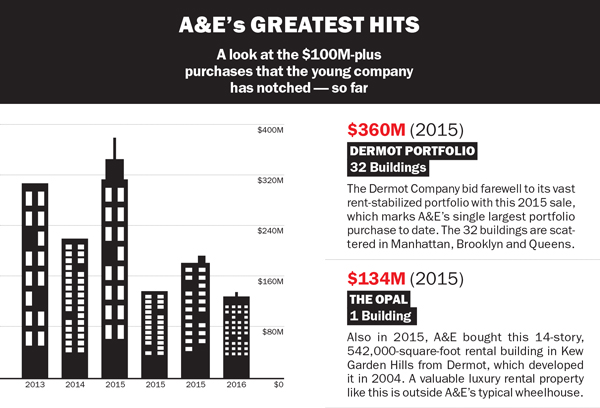

That tenacity has paid off in a big way at Eisenberg’s A&E Real Estate Holdings, which just six years after launching is now one of the biggest investors in the city’s multifamily market.

The Midtown-based firm has amassed over 12,000 New York City rental apartments at more than 200 buildings, which sources close to A&E estimate have a combined value of north of $3 billion. And as the market has slowed — and the buyer pool for portfolios worth more than $100 million has thinned out — A&E has found itself in an exclusive sandbox.

The firm now falls in line just behind major players like Related Companies, the LeFrak Organization, Blackstone and Cammeby’s International, according to a recent ranking of rental landlords by The Real Deal.

“He’s grown pretty dramatically, but not outside of his sweet spot,” said Jonathan Mechanic, the head of Fried Frank’s real estate group, which represented lender Mesa West Capital on A&E’s recent $133 million portfolio purchase in Queens.

Like its rivals in the multifamily space, A&E largely targets well-worn, heavily rent-stabilized buildings in the city’s remaining working-class areas. In other words, portfolios in need of extensive repair that come with serious baggage.

Like its rivals in the multifamily space, A&E largely targets well-worn, heavily rent-stabilized buildings in the city’s remaining working-class areas. In other words, portfolios in need of extensive repair that come with serious baggage.

But as the firm’s unit count climbs, the lawsuits are also piling up.

A&E is going head-to-head with a group of tenants who allege that the company overcharged them in rent. And last year it settled a lawsuit over two allegedly illegal tenant buyouts with the New York State Attorney General’s office.

Eisenberg said winning over tenants is not easy, particularly when buying properties that come with angry (and organized) residents and a laundry list of violations.

“It takes a fair amount of time to turn around the buildings we acquire,” Eisenberg said in a recent interview in Harlem at the Riverton Houses, the seven-building, 1,100-plus-unit complex A&E bought in 2015 for $200.9 million.

“If you buy a building that’s been run-down for decades and had an owner that didn’t respond to residents, it’s going to take time to earn their trust. The tenants have every right to be skeptical and not trust you,” he said. “It’s our job to prove to them we mean what we say.”

‘Urban’ dreams

Eisenberg, who is 46, grew up with younger twin brothers in an upper-middle-class family on the Upper East Side in the 1980s.

His dad was a real estate lawyer, and his mother headed a summer tennis camp.

Eisenberg attended the Trinity School, an elite private school where one of his classmates and friends was Harrison LeFrak, son of the real estate billionaire Richard LeFrak.

In 1993, after graduating from Cornell — where he was on the tennis team and where his father and brothers also went — he moved back to Manhattan and lived with his then-girlfriend at Peter Cooper Village.

He worked for Mayor David Dinkins coordinating re-election campaign events and for then-Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer. Eisenberg credits both of those political stints with schooling him in the diverse city neighborhoods far removed from his sheltered Upper East Side bubble.

“One morning you could be in Astoria, the next you could be in Northern Manhattan, or Bay Ridge,” Eisenberg said.

But the political bug didn’t last long.

Eisenberg left Democratic politics behind in 1996 and went to Brooklyn Law School, where he met his wife, Wendy, on law review.

Unlike his father — who practiced real estate law for 14 years before buying buildings himself — Eisenberg jumped immediately into the investment game.

In 1997, his father founded Urban American Management, which set up shop in West New York, New Jersey, after purchasing a roughly 1,000-unit portfolio in Hudson County. It was a family affair, with Eisenberg’s mother, Betsy, overseeing leasing and renovations, and his brothers later joining to head the operations and legal departments.

In 1997, his father founded Urban American Management, which set up shop in West New York, New Jersey, after purchasing a roughly 1,000-unit portfolio in Hudson County. It was a family affair, with Eisenberg’s mother, Betsy, overseeing leasing and renovations, and his brothers later joining to head the operations and legal departments.

The company rapidly grew in the NYC area and became one of the marquee private equity-backed investors that went on a multifamily spending spree in the mid-2000s amid the housing boom.

But in 2011, Eisenberg, who was the chief operating officer of the company, quit amid rumors of a family feud.

Eisenberg declined to comment on his departure as did a spokesperson for Urban American, which still has more than 6,000 units.

Sources close to Eisenberg, however, denied any internal animosity and said he simply made an “entrepreneurial” decision to break out on his own.

And shortly after he did, John Arrillaga Jr. — the son of a billionaire developer who built a Silicon Valley real estate empire — entered the picture.

When A met E

Eisenberg and Arrillaga Jr. — who met through their wives, longtime family friends —have a lot in common. They are both in their mid-40s, have family real estate fortunes, are married with three kids apiece and were separately described by one source as “quiet and reserved.”

They were also both eager to step out from the shadow of their successful family businesses and had similar views on how to run a multifamily investment firm, sources said. In 2011, after talking shop for years, they decided to launch A&E, along with Wendy, who handles property management.

The company’s first purchase was a 50-unit condo-turned-rental at 163 Washington Avenue in Fort Greene that it bought in 2012 for $31.5 million with New York REIT. The partners sold it for $38.1 million in 2015, records show.

Sources close to A&E said Eisenberg and Wendy relied on “a small savings account” — rather than family money — to buy their first building.

A&E’s initial three-person operation has now ballooned into staff of 400, 150 of whom are based in Midtown and the rest out in the field managing buildings, the firm said.

Arrillaga Jr., who declined to comment for this story, divides his time between New York and California, leading A&E’s acquisitions in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Silicon Valley, where the company has about $400 million in multifamily and office assets.

But in New York, Eisenberg — a family man who in February sold his Upper West Side condo for $7.2 million — largely runs the show.

And he often sticks to a formula: partner with a mix of endowments, pension funds and private equity firms, and make long-term multifamily investments. The company favors lower-risk investments with less leverage than some of its rivals — usually around 50 percent to 55 percent versus the 65 percent that’s become commonplace among the city’s multifamily buyers.

“I could get him a lot more leverage if he wanted it, but I’d rather he be around another 30 to 40 years,” said Jon Estreich, mortgage broker at Estreich & Co., which has worked with the firm.

The company’s long-term approach — investments start at 10 years and go up — stands in contrast to rivals like Treetop Development and Black Spruce Management, and has allowed it to clear about 7,800 violations to date, said sources close to A&E.

“We spend a good amount of time upfront understanding if a building has a large number of violations and what type of improvements are needed,” Eisenberg said. “We want to make sure that we have a clear plan in place for improving the property once we acquire it.”

But not all of A&E’s partners — some of which provide as much as 60 percent of the equity — share that long-term outlook.

Private equity fund AllianceBernstein has partnered with A&E, but mostly on shorter-term deals.

AllianceBernstein’s Brahm Cramer, who worked at Goldman Sachs in the mid-2000s and did deals with Einsenberg at Urban American, said his firm “seeks a higher return than an endowment fund” and therefore rarely backs A&E’s workforce-housing deals.

And A&E is not exclusively a long-term, low-risk investor.

The firm, for example, sold 11 Brooklyn buildings to Heller Realty for $206.5 million in 2015 after buying them up beginning in 2012.

The firm, for example, sold 11 Brooklyn buildings to Heller Realty for $206.5 million in 2015 after buying them up beginning in 2012.

Eisenberg relies on a small network of partners, brokers and lenders, the latter of which include Signature Bank and M&T Bank, records show.

“He’s well-capitalized and very by-the-book,” said Rosewood Realty Group’s Aaron Jungreis, who has brokered the majority of A&E’s deals.

Second-generation investors

In 2016, the city’s multifamily dollar volume tanked, hitting a five-year low of $14.1 billion. That was after logging a banner year of $19 billion in 2015, when giant portfolio deals — like the $5.3 billion Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village purchase and the $690 million, 24-building Caiola package — were in vogue.

But of the handful of $80 million-plus deals in 2016, A&E landed two of them, totaling 15 buildings and $222 million.

Still, it was the firm’s 2015 Riverton deal that took A&E to the next level and put the industry on notice.

As part of that deal, the firm agreed to keep most of the units affordable for 30 years and to make $40 million in renovations, including the construction of a new senior center and tenants’ association space.

One investor source called A&E the “second generation” of the institutional, private equity-backed multifamily investors. The first generation emerged in the 2000s, replacing long-term family ownership, but when the downturn hit, many of them took a financial hit, and “predatory equity” stepped in.

Vantage Properties was widely accused of being one of those predatory players, coughing up $1 million in a 2010 settlement with the AG for allegedly harassing long-term tenants as a way to force them out.

But Vantage was not alone. Other investors — Steve Croman and Ved Parkash, to name two — had problems ranging from tenant lawsuits to outstanding building violations that landed them on the city’s annual “worst landlords” list.

A&E contends, however, that it does not fall into that category and that its fast growth is tempered by its long-term horizon and below-average leverage.

But housing activist Kerri White of the nonprofit Urban Homesteading Assistance Board seemed doubtful that any major multifamily player could avoid being hard-hitting.

And in the Riverton deal, multiple sources said A&E outbid multifamily heavyweights Fairstead Capital and Larry Gluck’s Stellar Management.

“For these big portfolios, they’d have to be aggressive. How high can they go up in price in a competitive bid and [what can they] do to those buildings to still make a profit?” White said.

Gray matter

So is A&E a responsible investor that, while in the market to make money, avoids crossing into murky territory with tenants — or not?

Eisenberg contends that A&E’s ambition and pursuit of profit is not blinding its social ethics.

“I don’t give a whole lot of thought to how much the business is worth,” he said. “Instead, I worry about work orders, boilers running, taking care of residents’ problems and improving our properties.”

Still, since 2013, A&E has been hit with at least 16 lawsuits, largely alleging illegal rent overcharging and construction work negligence, according to TRD analysis of court documents.

Three of the rent overcharge suits against A&E were dismissed, records show. But two of the suits have raised questions — at least among some advocates — about A&E’s ethos.

One of those cases is the ongoing lawsuit from 68 current and former tenants at 22 buildings who claim A&E lied about apartment improvements in order to destabilize units. In October, when the suit was filed, an A&E spokesperson claimed 52 of the 55 allegations date back to prior ownership, and the other three that refer to A&E’s ownership were unfounded.

Activist Aaron Carr of the tenants’ rights group Housing Rights Initiative — which organized the tenant plaintiffs for the lawsuit — did not mince words when talking about A&E.

“If the ‘discounted rent’ is based on a fraudulent increase, it’s no longer a discount — it’s an overcharge hiding behind a larger overcharge,” he said. “A&E is like a car salesman who wants you to believe that a $25,000 car is worth $50,000, when it’s actually a lemon.”

Meanwhile, last summer, an A&E-led partnership agreed to a $540,000 settlement with the AG, who found two illegal tenant buyouts at the firm’s 91st Street condo conversion.

A source close to A&E said the settlement was “not the end of the world.”

“There was a certain gray area about how that issue should have been handled,” the source said. “That money went into their affordable housing pool, and they’re going to take it and do good with it.”

When asked about A&E’s rapid growth, a spokesperson for the AG said, “We are aware of other complaints against the company, and we encourage anyone subject to harassment or illegal practices to contact our office.”

Eisenberg, who declined to discuss the settlement, acknowledged that there have been growing pains.

“Do we make mistakes along the way? We do. We have a good-sized portfolio,” he said. “Things are always going to happen, but it’s what you do when you make a mistake — how you handle yourself — that counts.”

The firm denies that it ever illegally destabilizes its buildings.

“We’re not in the business of gentrifying neighborhoods or creating turnover,” Eisenberg said. “If we get a vacancy, we’re going to renovate it if the unit requires and follow all the rules of the city and state. Then we’re going to rent it.”

A source close to A&E said the firm has deregulated fewer than 175 apartments to date.

In some cases, A&E does, in fact, appear to try to right the wrongs of past owners.

Cynthia Allen, president of the Riverton Tenants Association, said the tenant group has had “no problems” with A&E. She said the company has been a major improvement over the complex’s past owners, CWCapital Asset Management spinoff CompassRock Real Estate as well as Rockpoint Group and Stellar, which jointly lost it to foreclosure in 2010.

“We were the poster child for foreclosure because of Larry Gluck,” Allen said. “And Stellar was bad, but CompassRock was worse. They were dragging people into court left and right, and rent receipts were just not correct.”

Time will tell whether A&E clears its name on its pending cases and whether its investments are successful — both for the company’s bottom line and for its tenants.

Speaking about the company generally, Fried Frank’s Mechanic said if Eisenberg’s shrewd tennis game is any indication of how he operates his company, the firm will only continue its upward trajectory.

“He’s not trying to kill the ball all the time,” said Mechanic, who plays with him on occasion. “He moves you out of position, all around the court, and he lets you make a mistake. He plays tennis like he manages his buildings.”

(To see a selection of properties owned by A&E Real Estate Holdings, click here)