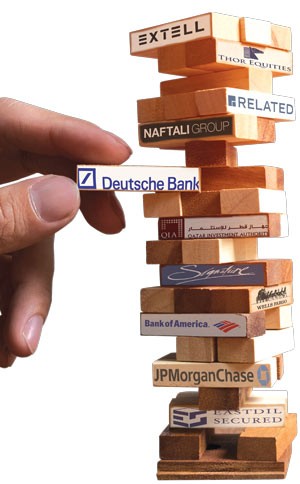

More than $13 billion is a pretty large sum, even by real estate standards. That’s how much Deutsche Bank [TRDataCustom] lent on New York City properties between 2011 and 2015, according to public records. But how much longer will the money keep flowing?

More than $13 billion is a pretty large sum, even by real estate standards. That’s how much Deutsche Bank [TRDataCustom] lent on New York City properties between 2011 and 2015, according to public records. But how much longer will the money keep flowing?

Ever since the 2008 financial crisis, the German banking giant has grappled with its own high debts and repeated executive shake-ups, and in January the company reported its first full-year loss since the financial crisis.

This June — for the second year in a row — the bank’s U.S. wealth management and transaction banking division failed the Federal Reserve’s stress test to see if it could withstand another downturn. Deutsche Bank shares that honor with only one other lender: Spain’s Banco Santander. To make matters worse, the Wall Street Journal reported in mid-September that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is seeking a $14 billion fine to settle a lawsuit over the bank’s role in the subprime mortgage crisis. That was followed by news on Oct. 14 that the Qatar Investment Authority, the bank’s largest shareholder, had concerns about its future.

And a day later, Bloomberg News reported that Deutsche Bank is considering shrinking its U.S. operations to cut costs. Those cutbacks are expected to primarily impact its investment banking division, while in a recently published strategy report the bank pledged to reinvest in its credit solutions business, which includes its real estate lending operations.

But despite that assurance, New York’s real estate players are starting to wonder how the market would respond if one of its most active financiers were to tighten the cash spigot — or turn it off altogether.

“They’re a major player,” said Michael Stoler of the New York-based lender and investor Madison Realty Capital. “If they didn’t lend to this market, there would be a void.”

Stoler said he doesn’t believe the firm’s troubles are as severe as the press has portrayed them in recent months, adding that it’s unlikely Deutsche Bank will bring its NYC real estate finance activity to a halt. But if the bank were to scale down its operations, it would hit the industry at a particularly inopportune time.

“Having Deutsche Bank leave would have a major impact,” he said.

Competing on risk

Once an obscure lender with little resonance beyond its native Germany, Deutsche Bank has emerged as a behemoth in New York’s real estate market over the past two decades. That shift began when the bank acquired New York-based Bankers Trust for approximately $12 billion in 1999.

Over the past year, Deutsche Bank ranked as the city’s third-largest commercial real estate lender by dollar volume, behind Signature Bank and JPMorgan Chase, according to the mortgage research firm Actovia.

Over the past year, Deutsche Bank ranked as the city’s third-largest commercial real estate lender by dollar volume, behind Signature Bank and JPMorgan Chase, according to the mortgage research firm Actovia.

The bank helped fund Ivanhoe Cambridge’s $2.2 billion acquisition of 3 Bryant Park with a $1.16 billion loan in early 2015. It is also backing Related Companies and Oxford Properties Group’s 10 Hudson Yards office tower with a $1.2 billion construction loan that closed this August, and co-leading a $1.5 billion financing package for the developers’ 1 million- square-foot Shops & Restaurants at Hudson Yards.

Many of the bank’s mortgages are traditional bank loans, held on its balance sheet, but Deutsche Bank is also one of the city’s most active originators of commercial mortgage-backed securities.

“Commercial real estate has always been an important part of [Deutsche Bank’s] DNA going all the way back to its Bankers Trust days, and will continue to be so in the future,” Matt Borstein, the bank’s global head of CRE, told The Real Deal.

The foreign bank matters to New York’s real estate market not just because of its total lending volume, but because it finances deals many others are reluctant to touch — most notably, new construction. Apart from the Hudson Yards loans, the bank’s recent construction financing deals in Manhattan include a $88 million loan for Related’s commercial project at 300 Lafayette Street, a $104 million loan for the Naftali Group’s condominium project at 219-223 West 77th Street and a $40 million loan for Sumaida + Khurana’s boutique condo development at 152 Elizabeth Street.

Matt Borstein

Amid a glut of new supply and a growing concern that the market has reached its peak, banks have increasingly shied away from construction lending in 2016. At this point in the cycle, “very few people are aggressive in that area,” said Marc Warren, a broker at Ackman-Ziff Real Estate Group.

Deutsche Bank is. The financial giant continues to finance major acquisitions and development projects in Manhattan and other major gateway cities.

“In real estate finance, you can only really compete in one of two ways: pricing or risk,” said capital markets broker David Eyzenberg. “They are competing on risk.”

Brokers told TRD that Deutsche Bank isn’t known as a particularly cheap lender, but it is more willing than most of its peers to finance construction or transitional properties. You won’t, on the other hand, see it funding multifamily walkup buildings in the outer boroughs.

Large banks “want to be at the top of their league tables, and there’s great prestige and profit in announcing that they are the largest and most active,” said Scott Singer, president of the Singer & Bassuk Organization. “In order to be the most active, it’s often necessary to become less selective.”

Still, none of the people interviewed for this story accused Deutsche Bank of reckless lending.

“I would argue that to be in the construction lending business today is really smart,” Warren said. “There is a lack of capital, so the risk-return is extremely attractive.”

“That’s leverage”

Things lined up differently for the bank in the past. In the years leading up to the 2008 crisis, Deutsche Bank invested billions of dollars in subprime mortgages, and in Manhattan it funded commercial portfolios at inflated prices. That came to haunt the bank when the real estate bubble burst, and it still weighs on the company’s finances.

A year ago, the bank announced a $7 billion quarterly loss and said it would lay off 35,000 employees. Meanwhile, the bank’s core capital as a share of total liabilities is 3.6 percent. That’s well below Wells Fargo’s 8.3 percent, JPMorgan’s 8.1 percent and Bank of America’s 7.2 percent, which means Deutsche Bank has less of a buffer to protect it against another major downturn.

Though Deutsche Bank has had an office in Manhattan for decades, its reign as a local powerhouse only really began with its acquisition of Bankers Trust — the work of Josef Ackermann, a flamboyant Swiss banker. Ackermann became the company’s first non-German CEO in September 2002 and pursued an aggressive growth strategy. In the era of high leverage and booming markets, Deutsche Bank piled on more debt than most of its peers.

Though Deutsche Bank has had an office in Manhattan for decades, its reign as a local powerhouse only really began with its acquisition of Bankers Trust — the work of Josef Ackermann, a flamboyant Swiss banker. Ackermann became the company’s first non-German CEO in September 2002 and pursued an aggressive growth strategy. In the era of high leverage and booming markets, Deutsche Bank piled on more debt than most of its peers.

In New York’s real estate industry, the bank also earned a reputation as a precarious lender leading up to the collapse. In August 2003, developer Harry Macklowe was about to buy the GM Building for $1.4 billion — a record price at the time. But 10 days before the scheduled closing, his lender Wachovia suddenly got cold feet, according to the book “The Liar’s Ball” by Vicky Ward. So Macklowe’s attorney called Deutsche Bank’s then-head of U.S. commercial real estate lending, Eric Schwartz, who was playing golf in Ireland. Schwartz immediately left the golf course, and 10 days later Macklowe had a $1.15 billion loan in the bank. Four years later, in 2007, Deutsche Bank lent Macklowe another $5.8 billion to finance his $7 billion acquisition of the Equity Office Properties New York portfolio. “Think about it. An individual with $50 million in cash basically bought $10 billion worth of real estate… that’s leverage,” Mike Fascitelli, at the time president of Vornado Realty Trust, told Ward. He also called the bank’s GM Building loan “incredibly aggressive.”

Then the financial crisis hit in 2008. Unable to refinance, Macklowe defaulted on his debts and lost both the GM Building and the Equity Office portfolio. The crisis, and the write-offs it incurred, marked a watershed moment for Deutsche Bank’s New York real estate lending business. In 2009, Schwartz and Jon Vaccaro, another top commercial lending executive, left the bank. Jonathan Pollack, a young executive who previously worked in Deutsche Bank’s London office, took over.

Between 2011 and 2014, he expanded the bank’s annual lending volume in New York more than 10-fold.

Gary Barnett

Pollack then left Deutsche Bank for the Blackstone Group in June 2015, and Borstein, who had joined the bank from Eastdil Secured in 2010, became the man in charge of the bank’s commercial real estate lending. Ed Adler, who joined the bank from Citigroup in 2011, stayed on as head of CRE loan originations for North America.

Pollack’s departure coincided with a leadership shuffle in Frankfurt. Just days earlier, the bank’s co-chief executives, Anshu Jain and Jurgen Fitschen, resigned amid lackluster overall performance and were replaced by John Cryan. In April 2015, the bank agreed to pay $2.5 billion to settle charges that it helped rig the London Interbank Offered Rate, which Cryan later said “really hit morale and confidence” within the bank.

Pollack’s departure also seemed to underscore a general post-2008 power shift away from Wall Street banks and toward less tightly regulated asset managers and private equity firms like Blackstone.

Still, there are advantages to being a big Wall Street bank.

Borstein said that part of Deutsche Bank’s competitive advantage is its ability to originate large, complicated construction loans.

The lender’s philosophy, he said, is “to be very important to your biggest clients on their most important projects.” Building up relationships is a key part of that strategy, he argued, since developers are “going to go to the guys they worked with in the past.”

Borstein also said that the bank has become more cautious about construction lending, largely retreating from such lending in the condo and hotel sector. He added that reduced competition in the field has pushed up profit margins.

Full steam

In 2011 and 2012, Deutsche Bank issued $325.7 million and $424.4 million, respectively, in debt on New York properties. That figure jumped to $3.04 billion in 2013, $5.45 billion in 2014, $4.49 billion in 2015 and $3.65 billion in 2016 to date, according to data from Actovia and the bank.

Debt brokers said that apart from its willingness to lend, the bank’s main competitive advantage is the broad range of financing services it offers, including traditional senior loans, construction financing, mezzanine debt, private banking, and other tailored mortgages through its special-situations group.

Borstein called the wide range of products “one reason our clients keep coming back to us.” And borrowers may be willing to pay more for financing if they are confident that Deutsche Bank will help fill other parts of the capital stack or lend on future projects, according to several sources.

Another cash cow for the German bank is its prominent CMBS business, which allows it to issue big-ticket loans without having to actually spend much of its own money.

“They’re only warehousing the risk for a short time until they flush the toilet, so to speak,” Eyzenberg said.

Deutsche Bank was the fourth-largest issuer of U.S. CMBS in the first half of the year, with $3.6 billion in origination volume, according to Commercial Real Estate Alert’s league table, down from $10.5 billion in the same period in 2015.

Virtually all CMBS issuers saw their deal volume fall in early 2016 amid global bond-market volatility. And CMBS issuance may become more difficult going forward. As of this December, new risk retention rules will go into effect requiring providers of securitized commercial debt to keep at least 5 percent of their loans on their books.

This could be particularly challenging for Deutsche Bank, which is looking to shrink its balance sheet and now faces stiff rules from European regulators on the types of assets it can hold, Ackman-Ziff’s Warren said.

Borstein dismissed the suggestion that risk-retention rules could have an impact on the bank’s CMBS business, arguing that any bonds it would hold are “no different” than the $20 billion in real estate loans the bank currently holds on its balance sheet.

Loyal customers

Deutsche Bank is known to place a strong emphasis on personal relationships with its borrowers, and it has done repeat business with many big-name sponsors.

Joseph Sitt’s Thor Equities, for one, has taken at least seven loans from the bank for its New York commercial properties since May 2014, according to city records. Gary Barnett’s Extell Development is another repeat customer. Barnett recently scored a $500 million Deutsche Bank construction loan for his condo development One Manhattan Square. The bank also financed the developer’s January 2014 acquisition of the Ring portfolio, among other deals and developments.

Related, meanwhile, in addition to landing $88 million in financing from Deutsche Bank in May 2016 for the developers’ boutique office and retail project at 300 Lafayette Street, nabbed a $125 million acquisition loan for a High Line development site at 511-525 West 18th Street that Related purchased in January 2014.

And in the past 10 months, Deutsche Bank teamed up with Goldman Sachs, Bank of China and other institutional lenders to provide $2.7 billion in construction debt for Related and Oxford’s Hudson Yards megaproject.

Institutional borrowers such as Thor, Extell and Related have the strongest reputations among lenders and would quickly find financing from other institutions if Deutsche Bank were to scale back its U.S. operations, sources said.

Barnett, however, said that he won’t need to do so.

“Deutsche Bank stands for Bank of Germany,” the Extell chief told TRD, referring to the lender’s political and economic importance to the country. “I just do not believe they could ever possibly go under.”

He said the $500 million loan for One Manhattan Square was “difficult to obtain” amid a general lender pullback from ground-up condo construction finance. “The relationship mattered to them, and they realized what an extraordinarily conservative loan it was,” Barnett said, adding that the loan-to-cost ratio is below 50 percent.

“We have a good long-term relationship,” he said. “They’re flexible, and you can talk to them.”

Representatives for Thor and Related did not return requests for comments.

Singer of Singer & Bassuk argued that the real estate industry would do just fine with a scaled-down Deutsche Bank. “I don’t think there’s any single institution whose market share is large enough in New York that simply removing [the bank] would have a measurable impact across the market,” he said.

But it may be a different story for the bank’s most loyal customers.

“For owners or developers who have sole-sourced their financing from Deutsche, it could be catastrophic,” Singer explained.