It started as a lease expansion.

It started as a lease expansion.

But Google — in its quest for dominion over Chelsea and the Meatpacking District — wanted more.

The technology giant first moved into the Chelsea Market building in 2007 with 108,000 square feet of office space at the 1.2 million-square-foot property. Five years later, it sank its teeth into another 94,000 square feet.

As leases expired and tenants moved out, Google showed a level of hunger not even found in the building’s beloved ground-floor food hall.

By last year, the company’s turf had expanded to roughly one-third of the building at 75 Ninth Avenue, which is also home to Major League Baseball, the Food Network and NY1 News. Sources familiar with Google’s negotiations with the building’s owner, Jamestown Properties, said the tenant was looking for opportunities to grow its operation at the building while those other leases remained.

Jamestown received several unsolicited offers for the property over the past few years. But as Google’s appetite has grown, its recent bid for the asset won the landlord over, according to multiple sources. Instead of focusing exclusively on the lease, conversations with Jamestown veered towards an acquisition — one poised to rock a slumping real estate marketplace off its axis. As The Real Deal first reported last month, Google agreed to buy the entire property for about $2.4 billion in what would be the second-priciest deal for a single building in New York City history. Representatives for Google and Jamestown did not respond to requests for comment.

The 3.8-acre, full-block office and retail building is also one of the most recognizable in the city, with a food hall that draws roughly 6 million visitors per year.

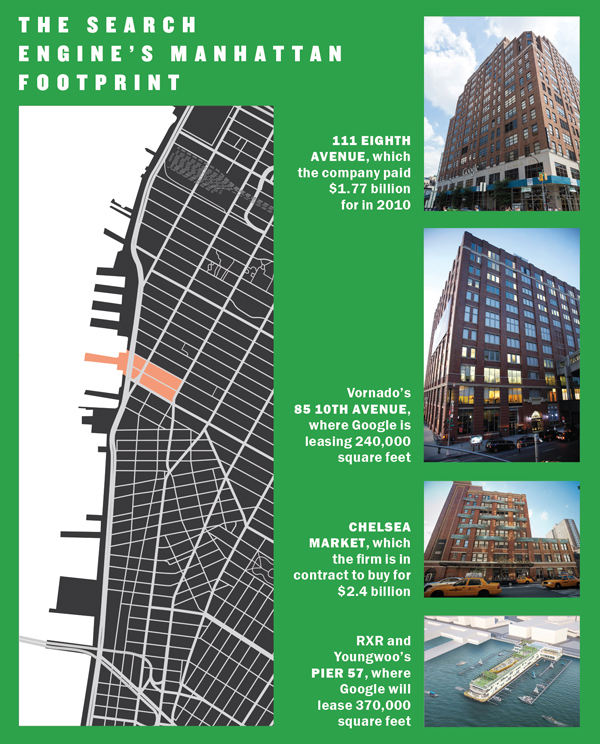

If nothing else, the move proved that Google has been playing the long game. Between its monster $1.77 billion deal for 111 Eighth Avenue in 2010 and its lease deals at 85 10th Avenue and the upcoming Pier 57 project, Google has assembled a fiefdom that stretches along West 15th Street from Eighth Avenue out to the waterfront pier.

And with at least $4 billion in NYC real estate acquisitions alone, the company is earning a serious reputation as a local property owner and operator. Marcus & Millichap’s Eric Anton, who is not involved in the deal, said that Google’s latest deal gives it the buying power to further transform the office leasing and investment-sales markets in Chelsea and the Meatpacking District .

And with at least $4 billion in NYC real estate acquisitions alone, the company is earning a serious reputation as a local property owner and operator. Marcus & Millichap’s Eric Anton, who is not involved in the deal, said that Google’s latest deal gives it the buying power to further transform the office leasing and investment-sales markets in Chelsea and the Meatpacking District .

“Behemoths like to create their own private environments,” Anton said. “A couple of these users could buy more of their own facilities, but a deal like this — at a staggeringly high price — won’t ignite a trend because there is only one Google.”

Google, a real estate history

After Larry Page and Sergey Brin founded Google in a garage in Menlo Park, California, in 1998, the firm rapidly grew into the multibillion-dollar multinational tech conglomerate.

When it came to real estate, it only took Google a few years to make a major investment. In 2004, the company built a corporate headquarters known as the Googleplex at 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway in Mountain View, in the heart of California’s Silicon Valley. The campus initially spanned 2 million square feet of offices. (In 2015 — the same year Google restructured to exist under its new parent company, Alphabet — the campus expanded to 3.1 million square feet.)

The company’s next big move was to build a presence in New York, which to date represents its second home state and splashiest real estate dealings.

Google inked its first Manhattan deal on Dec. 31, 1999, when it signed a lease at 1440 Broadway in Times Square. That office space grew to 170,000 square feet over the next six years, according to lease documents and news reports.

The space soon became too cramped for Google’s more than 500 employees, and the company’s executives looked to Midtown South. In 2005, they signed a lease for 300,000 square feet at 111 Eighth Avenue, a 2.9 million-square-foot, block-long office building then owned by Taconic Investment Partners, Jamestown and a state pension fund. At the time, sources told the New York Times that Google liked the location because the building sat on top of a major internet fiber-optic line.

While also planting a flag across the street at the Chelsea Market building in 2007, Google was determined to keep growing at the 18-story Eighth Avenue property. In what remains one of Google’s biggest real estate purchases worldwide, the company paid $1.77 billion for 111 Eighth Avenue in 2010.

Over the next several years, Google tried to muscle existing office tenants out of the building. The company failed to persuade Nike and advertising agency Deutsch to accept buyout offers in 2012. The tenants ended up staying until 2014 and 2015, respectively. WebMD accepted an undisclosed sum to vacate in 2015. Although Google owns the property, it’s unclear how much space it occupies in the building. One source said it has about 800,000 square feet.

It appears that Google’s growth strategy at 111 Eighth — years of steady leasing expansions accelerated by a monster purchase — is being mirrored across the street at Chelsea Market, sources said. Even before news broke last month that the tech giant was planning to buy the property, several of building’s office tenants began reducing their space. MLB, for example, will have fully relocated to Rockefeller Group’s 1271 Sixth Avenue by 2022.

Google has already started to piece together something of a second headquarters in Manhattan. That stronghold not only puts the tech giant in the spotlight for its real estate plays but also has market observers questioning Google’s greater intentions in New York.

Google has already started to piece together something of a second headquarters in Manhattan. That stronghold not only puts the tech giant in the spotlight for its real estate plays but also has market observers questioning Google’s greater intentions in New York.

Eight years later

If the Chelsea Market deal holds, it would not only be the second-priciest building sale in the city’s history but would also boast the highest price per square foot among its cohorts in the $2 billion club — an astronomical $2,000 if the deal closes at $2.4 billion.

The price per foot is even more significant when contrasted with Google’s purchase of 111 Eighth Avenue, which penciled out to $610 per foot. That was the biggest investment-sales trade of 2010, and one of the largest ever in terms of dollar volume. While the market this year is lackluster, the price per foot for the Chelsea Market deal is more than triple that of 111 Eighth. But the striking differences in price don’t surprise some.

“Look at Google’s share price and market cap in 2010 versus now,” said Anton, pointing to its parent’s market cap of nearly $800 billion. He added that since only a handful of tech behemoths can pull off real estate deals like Google has in New York, a larger owner-user trend among other Silicon Valley firms is unlikely.

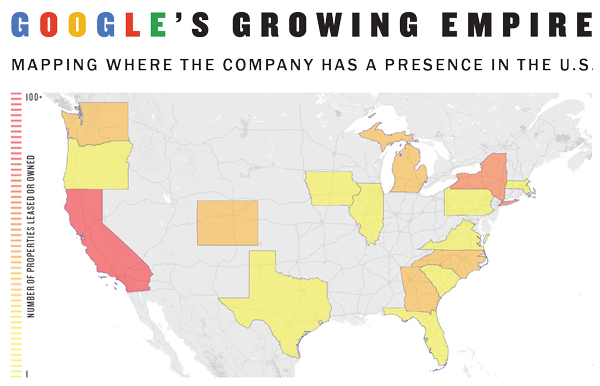

Indeed, Google is not the same company it was in 2010. Apart from the Alphabet restructuring, it now has 74,000 employees worldwide as well as more than 70 offices and 15 data centers in 50 countries, according to the company.

It has also been aggressively buying up vacant industrial plots and office buildings in the San Francisco Bay Area in recent years, including an $820 million purchase of 52 buildings in Sunnyvale in July. Although the acquisitions outside of New York are significantly larger in terms of gross acreage, the pricing doesn’t compare.

Alphabet’s global real estate assets have an estimated value of $14.5 billion, according to Real Capital Analytics — roughly 30 percent of which is concentrated in two New York City buildings.

The Chelsea Market building’s 290,000 square feet of development rights, meanwhile, shows even more untapped potential for the company’s real estate holdings. Brian Strout of City Center Real Estate — which specializes in air rights transactions — said utilizing the rights would not necessarily be motivated by profit.

“They want to control as much as possible,” he said. “It’s imperative for them to meet future expansion needs, whether they use the air rights on day one or later on.”

The Chelsea Market deal, which is expected to close in the next two months, has brought the city’s top investment-sales brokers. Cushman & Wakefield’s Doug Harmon, a longtime adviser to Jamestown, is representing the seller, and CBRE’s Darcy Stacom is representing Google in the deal, sources said. The two represented opposite sides in Google’s 111 Eighth purchase as well, when Harmon was still at Eastdil Secured. Both declined to comment for this story.

“These are very different times and points in the market,” said Zev Holzman, a tenant-representation office leasing broker at Savills Studley who was not involved in the deal. “Eight years is an eternity.”

Untapped value

The $2.4 billion figure also speaks to how much the real estate itself has appreciated over more than a century. The New York Biscuit Company developed a Romanesque-style complex of six-story bakeries on the site starting in 1890. And in 1959, the biscuit manufacturer, which had merged to become the National Biscuit Company, vacated the premises and sold the then 22 structures to investor Louis Glickman for an undisclosed price.

But it wasn’t until the 1990s that the real estate became a titanic cash cow. Developer Irwin Cohen and a syndicate of investors paid about $10 million for the foreclosed mortgage on the majority of the buildings, and then redeveloped the property into what it is today, with the Chelsea Market food hall opening in 1997. The development is a collection of 17 historic buildings, including a former Nabisco factory complex.

More investment muscle soon jumped aboard: Belvedere Capital Real Estate Partners and Angelo, Gordon & Co. joined in 1999, followed by Jamestown in 2003. Then, in 2011, Jamestown bought out its partners for $225 million, valuing the property at nearly $800 million.

Since then, the enclosed Chelsea Market has expanded to house 60 different restaurants and shops. The food hall-anchored retail component occupies 225,000 square feet of the ground floor and lower level, while the offices above span 975,000 square feet.

With the building under Jamestown’s watch, change has always been on the table. The firm had hoped to take advantage of the unused air rights to build eight stories of additional office space on top of the western portion of the complex.

The developer faced community opposition for initially seeking to build an adjoining hotel, but instead received unanimous City Council approval to expand the office component in November 2012. The plans fell on the back burner while Jamestown searched for an office tenant to sign for the space. That deal, had Jamestown acted on it, would have required the firm to provide $19 million toward the High Line and nearby affordable housing. In 2016, Jamestown president and principal Michael Phillips instead shifted his sights toward pumping as much as $50 million into expanding the retail.

After TRD broke the news of the sale to Google, residents and Chelsea Market devotees expressed concerns over the fate of the retail, which expanded into the building’s basement in August with a food-centric 30,000-square-foot hub called the Chelsea Local. Those concerns were not only pegged to the retail market’s recent troubles but to the perception of Google as a user first and owner second.

But industry sources say any changes the company makes to the property should not impact the food hall in the near term. Strout argued that whatever Google does with the food hall, it is not in the company’s interest to get rid of it.

“If they gutted it and built one big cafeteria, that would be really boring,” he said. “But if they just reconfigure the food options or close shops while they install elevators, for example, that’s all within their prerogative.”

One for the books

New York City’s elite $2 billion club of trophy office buildings is gaining a new entrant.

Google’s massive pending Chelsea Market buy would be the fifth in the history of Manhattan to cross that threshold in an outright sale.

The four other properties in that group are the GM Building at 767 Fifth Avenue ($2.8 billion, or $1,400 per square foot), 11 Madison Avenue ($2.3 billion, or $973 per square foot), 3 Bryant Park ($2.2 billion, or $1,875 per square foot) and 245 Park Avenue ($2.2 billion, or $1,127 per square foot). TRD excluded partial-stake deals for the purpose of this analysis.

Like several other monster deals of late, including the $5.3 billion trade of Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village and the $905 million pending sale of Starrett City, the property was not widely marketed, sources said.

The transaction would give an early boost to the city’s investment-sales market this year, which saw only one single-building deal exceed $2 billion in 2017: Chinese conglomerate HNA Group’s purchase of 245 Park Avenue. Ironically, HNA is now looking to sell that tower as part of a $16 billion fire sale amid mounting debt.

Perhaps even more notable is that Google’s latest deal marks a rare monster investment-sales trade on the border of Chelsea and the Meatpacking District. The neighborhoods are part of the booming Midtown South office submarket, but has always been less prestigious than Midtown in terms of big-ticket investment sales.

“It’s emblematic of the current state of Midtown South,” Holzman said. “There is a severe shortage of large-floor-plated buildings, and the few that do demand a premium. This further solidifies it as a neighborhood for corporate America.”

Aetna, for example, leased 145,000 square feet a block south at Vornado and Aurora Capital Associates’ 61 Ninth Avenue, though its plans to move in fell apart after CVS agreed to buy the health insurer.

While not in the same league as the two Google deals, Chelsea has seen its share of office sales in recent years. Swiss fund AFIAA picked up Normandy Real Estate Partners’ 119-125 West 25th Street for $906 per square foot ($125 million) in 2016, and Savanna paid $872 per square foot (or $126 million) for 31-35 West 27th Street last year.

In an incentive to further Google-ize the neighborhood, the company is even offering its employees discounts for apartments in the area. Workers interested in a $13.4 million, seven-story townhouse at 338 West 15th Street would receive a $1 million discount, CityRealty reported in February.

On Vornado Realty Trust’s fourth-quarter earnings call in February, CEO Steve Roth said the Google deal “further validates New York as a talent center” for major businesses and asserts “the importance of the West Side” as an emerging office destination.

But the flashiness of the purchase may lead to other challenges for the giant in the public eye.

“There’s talk in the media of concerns about the power of Google and others, to the point of calling them monopolies,” Anton said. “And now a company like Google brings even more scrutiny by buying Chelsea Market. That’s an amazingly high-profile move, but it also further ingrains this idea people have of the ‘evil empire.’”