The bombshell news last month that New York City’s top two investments sales brokers, Doug Harmon and Adam Spies, decamped for Cushman & Wakefield after years at Eastdil Secured is still being digested and dissected in the industry.

The move — which Eastdil’s CEO, Roy March, was told about on the phone just minutes before it was reported in the press — shifts the playing field in the ultra-competitive world of selling $1 billion-plus trophy New York City properties.

It also unlocks Eastdil’s long-standing stranglehold on the upper echelon of the investments sales market, a reality that sources say could ratchet up poaching and broker churn at the two firms and beyond.

This kind of high-level reshuffling is something the industry hasn’t seen in decades.

“Eastdil is certainly changed forever,” said Eric Anton, senior managing director at the national real estate capital intermediary HFF. “Interestingly, during the last 20 years, many of the top brokers in the city have not changed. Only their business cards have changed.”

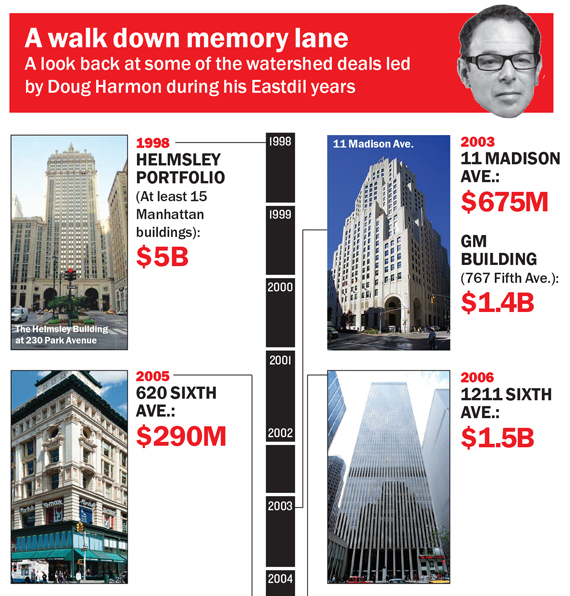

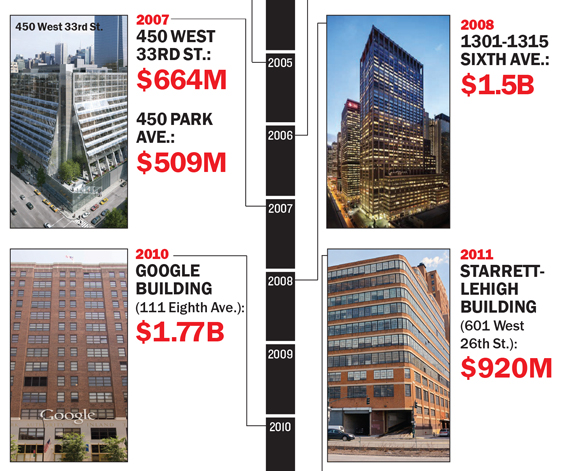

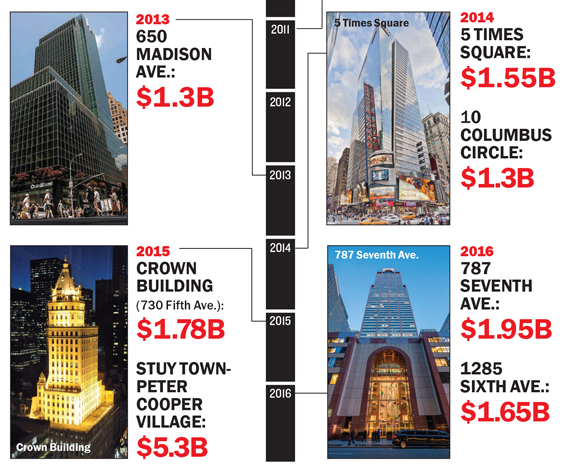

Indeed, Harmon and Spies — who joined Eastdil in 1993 and 1999, respectively — both started their commercial brokerage careers as newbies at the firm. But with the help of the long-haired rainmaker March they catapulted themselves (and their company) to the top of the city’s investment sales food chain, outselling their closest competitors by billions of dollars a year.

According to Cushman & Wakefield, the Harmon-Spies duo has done $200 billion in sales in more than 500 transactions during their careers.

That firepower, of course, is why Cushman — which despite its global dominance has lagged far behind its rivals on the New York investment sales front — wooed them to begin with. And their presence is already having a big impact on existing Cushman brokers, who have been advised to turn over all New York investment sales deals priced at $75 million or more in exchange for a referral fee, sources familiar with internal discussions at the firm told The Real Deal.

Whether that new system pushes Cushman brokers to look for the nearest exit is something the industry will be watching closely. So is whether the power duo can actually transform the global juggernaut into a true power player on the New York investment sales scene in the coming months — or perhaps years.

And although Harmon and Spies reportedly left Eastdil on good terms, their departure pits the two brokerages against each other, creating what could be a new industry rivalry. Industry observers will also be looking at both firms as they feverishly try to put up strong sales numbers in an uncertain market — one that’s seen a drop in sales at the same time that there’s been a rise in price per square foot.

As one executive at a rival brokerage put it: “You’re going to see who was really able to execute: the platform or the people.”

How secure is Eastdil?

Harmon and Spies have long been Eastdil’s two most recognizable names in New York, but all of that changed on a Thursday afternoon last month.

That’s when March received the industry’s equivalent of the 3 a.m. phone call.

He had just gotten off a plane in New York after delivering the keynote address at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business’ annual real estate conference, which is located just two miles from Cushman’s new global headquarters.

Harmon and Spies were both on the other end of the line and dropped the bomb: They were leaving Eastdil, effective immediately.

The news broke minutes later. It was clear from the outset that this was not a standard “broker jumps ship” story. Rather, it was an industry game changer with high financial consequences for all of the parties involved.

In 2015 alone, Eastdil brokered a record $22.7 billion in New York City investment sales, according to TRD’s latest ranking, which evaluated the top 40 firms citywide. To put that number in perspective, CBRE placed second with $8.8 billion in sales, and Cushman clocked in at No. 3 with a measly $3.4 billion. (That’s despite the thousands of employees those firms have globally versus the few hundred Eastdil has on its payroll.) Eastdil’s 2015 deals, which were largely brokered by Harmon and Spies, netted the firm an estimated $65 to $80 million in commissions, according to TRD’s calculations.

The duo is credited with more of the city’s monster sales than any of their rivals. The Chetrit Group and Clipper Equitys’ sale of the $1.78 billion Crown Building and the $5.3 billion sale of Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village are just two of their recent deals.

But sources told TRD that March cannot be underestimated. They noted that the CEO was, at least in some cases, feeding Harmon and Spies leads behind the scenes.

According to sources inside Eastdil and others involved in its deals, Anbang Insurance’s 2015 $1.95 billion purchase of the Waldorf Astoria from the Blackstone Group was handled by March, Lawrence Wolfe and Mark Schoenholtz — not Harmon and Spies, who were often publicly credited.

Harmon and Spies were also publicly buoyed by other deals that March reportedly led, including Ivanhoe Cambridge’s stake purchases of 330 Hudson Street and 1211 Sixth Avenue, as well as its $2.2 billion purchase of 3 Bryant Park.

March’s dealmaking chops are somewhat legendary.

Back in 2007, March and his team brokered Blackstone’s $39 billion purchase of Sam Zell’s Equity Office Properties Trust portfolio. March then brokered Blackstone’s sale of a $7 billion chunk of that portfolio to Harry Macklowe.

According to Vicky Ward’s 2014 book “The Liar’s Ball,” Macklowe once described March like this: “Look at that freak, because not only does he have long hair — like he’s Robin Hood — he’s got shit-kicker boots, with these pointy toes, like he’s going to kill a cockroach in the corner.”

A leading sales broker who is not at Eastdil said: “Harmon and Spies aside, March is the straw that stirs the drink. He is one of the world’s top brokers.”

Another source close to Eastdil described Harmon and Spies’ prolific dealmaking like this: “They were successful because they had scores of people — an international support system — behind them. Through Eastdil, they had access to China and the Middle East. Doug and Adam weren’t getting on planes.”

Regardless of who deserved credit on a handful of deals, there is no disputing that Harmon and Spies are a force of nature and that their departure leaves a giant void at the firm. That’s not to mention that they are also bringing managing directors Kevin Donner, Adam Doneger and Joshua King to Cushman with them, the firm confirmed.

But Eastdil — which has offices in 13 cities worldwide, including Los Angeles, Hong Kong and London — is already adjusting its New York operation to deal with the exit.

Although sources said there are no plans to make new hires right away, they noted that Jeff Scott, a senior managing director specializing in structured transactions, will relocate to New York from Washington, D.C., and that David Lazarus, who is already based in New York but focused on the investment banking side, will now also work on investment sales.

Meanwhile, along with March, company chairman Ben Lambert and president Michael Van Konyenburg are reportedly prepared to tackle more deals and continue to serve as “player-coaches,” sources said.

March told TRD that Eastdil would solider on, noting that “no individuals are greater than the cause.”

“Our intention is to do what we’ve always done — to support our clients and utilize our talent within the firm,” he said in a phone interview.

Brokers who spoke to TRD said they did not think the Harmon-Spies departure was the nail in Eastdil’s investment sales coffin in New York.

JLL’s Yoron Cohen — who was on a high-powered team that left Cushman in 2010 — said Eastdil “will do just fine,” noting that it has a strong pipeline of up-and-comers.

“They will get younger versions of those who left, some of whom are in their system already,” Cohen said. “The only issue is Wells, who owns them and is in a bit of trouble now.”

The Wells that Cohen was referring to is, of course, Wells Fargo, Eastdil’s parent company.

Sources speculated that the high-profile investigation into sham bank accounts — a scandal that came to light in September — actually prompted Harmon and Spies to make the move. But sources close to Eastdil disputed that and said Harmon and Spies left on good terms. One noted that it was not “World War III or the War of the Roses.” They simply left over something basic and old fashion: money.

“The reason for them leaving was over a paycheck,” a source said. “Maybe they had concerns, but if someone says the reason is Wells Fargo, it’s an excuse.”

“The reason for them leaving was over a paycheck,” a source said. “Maybe they had concerns, but if someone says the reason is Wells Fargo, it’s an excuse.”

Insiders said the two brokers felt that they were leaving too much money on the table because of Eastdil’s salary-and-bonus model, which is steeped in the company’s financial firm roots.

“Given the same business, these guys stand to make a lot more money,” said Joel Herskowitz, the COO of Lee & Associates NYC. “If you have a year like 2008 or 2009, salary is a good thing. Even in a so-so market and you do less business, you can do an awful lot better with a commission than salary-and-bonus.”

Harmon had often complained that Wells Fargo took too big a bite out of Eastdil’s profits, the commercial real estate newsletter Real Estate Alert reported, citing unnamed sources. The publication also reported that Eastdil did not make Harmon and Spies a counteroffer.

But sources said Cushman reportedly offered the team a large sum — possibly as high as nine figures — to be paid out over years. While their exact terms and compensation packages are unclear, the move is having a big ripple effect at both firms.

Cushman’s calculation

If there’s one person in Cushman’s New York operation who is likely to feel the impact of Harmon and Spies more than anyone, it’s Bob Knakal.

Knakal and his partner, Paul Massey, of course, sold their namesake New York City investment sales firm to Cushman for $100 million in early 2015, giving the larger firm overnight domination in the outer boroughs. (Evidence of that can be found in the 2014 numbers. TRD’s ranking that year found that Cushman brokered only $875 million that year, while Massey Knakal did $3.8 billion.)

Now, nearly two years after the acquisition, Knakal, the chair of New York investment sales, has settled into his top-dog role.

But it’s unclear whether Cushman carved out an exemption for Knakal, Massey or any other brokers on its new declaration that Harmon and Spies will be brought in on all deals valued at $75 million and up. It’s also unclear if any of Cushman’s top brokers stand to gain from their deals in other ways — because details about whether they own stakes in the company are not public.

For his part, Knakal has handled 16 deals in the $75 million-plus category in the last two years, according to data provided by Cushman.

He represented the Jevohah’s Witnesses in the $340 million sale of the Watchtower building in Dumbo to Kushner Companies, CIM Group and LIVWRK in August, and he brokered the World Wide Group’s $300 million sale of an Upper East Side development site to Kuafu Properties last year.

Ironically, the “referral fee” practice is modeled on the signature “territory” system devised by Massey Knakal. Under that system, any broker who found a deal in someone else’s territory would hand it over to that agent in exchange for a referral fee.

Applying the same concept to deals of a certain price, however, appears to be a first.

And it doesn’t just have an impact on Knakal. James Nelson and Stephen Palmese both came over from Massey Knakal, and it’s likely they will be affected as well.

A Cushman spokesperson declined to comment on how the practice would be implemented, but some said it could discourage star brokers from joining the firm and even prompt current agents to leave once their contracts expire.

Knakal declined to comment directly on the $75 million referral fee, but he said the addition of Harmon and Spies, who are both coming in as chairmen of capital markets, is a good thing. “No matter how good you are or think you are, you can get better by working with some of the best in the industry,” Knakal said. “I equate it to: If I could play hockey with Wayne Gretzky and Mark Messier, I would jump at it.”

For Cushman the one-two punch of buying Massey Knakal and then landing Harmon and Spies comes after several rough years.

In 2010, the firm lost its own leading capital markets team of Richard Baxter, Jon Caplan, Yoron Cohen and Scott Latham to JLL. The firm is also reeling from a mass exodus in its New England investment sales division in September 2015, when Rob Griffin, Boston’s top investment sales broker, left for Newmark Grubb Knight Frank and took 70 people with him.

So this latest coup could not have come a moment too soon, especially for the firm’s relatively new CEO Brett White, who was brought on in March 2015 at global real estate giant DTZ, which then acquired Cushman in a $2 billion deal a few months later.

The acquisition sparked talk that the joint mega firm was looking to go public.

This past June, White told British business magazine Estates Gazette that given the state of the capital markets, “we would not want to do anything this year.”

In addition, he said: “Even if an IPO were to occur in 2017, 2018 or 2019, it will take time.”

Analysts say that the firm still needs to boost its revenues and improve its margins to do that. That provides yet another explanation for why White — who is said to have led the wooing of Harmon and Spies — wanted new blood. In the meantime, late last month, Cushman saw a leadership shake-up, which replaced Ron Lo Russo with John Santora as president of the brokerage’s New York tri-state region. Lo Russo will head up the firm’s agency/leasing practice in the region. How those moves play into the firm’s overarching strategy is uncertain, but the company clearly has its eye on the revenue ball.

“Cushman is looking to bulk up and generate momentum across multiple channels, including capital markets, where they are trailing their peers,” said Mitch Germain, an analyst with Manhattan-based investment bank JMP Securities. “Eastdil owns the New York market.”

Brandon Dobell, a partner at the global investment bank William Blair & Co. and a veteran industry analyst, agreed, but added that “building a pipeline takes a while.”

“You’re lucky if the guy [you hire] is doing business in six months, let alone 24 to 36 months,” he said.

“I’d be remiss to say Cushman will be No. 1 in the New York investment sales rankings,” Dobell added. “To see the move really change Cushman could take years, and by then, the company could have attracted even more high-profile talent.”

Nat Rockett — who ran Cushman’s New York investment team with Helen Hwang until September 2015 when they both left for other brokerages — said deciding when to move to a new shop comes down to timing the market. “It’s much more appealing to move when the market sucks because you’re leaving behind less,” said Rockett, who is now at Marcus & Millichap.

Harmon declined to be interviewed for this article, but he issued a statement that addressed the timing of the move. “The market is transitioning from a period when cap rate compression and financial engineering drove significant value, to a period where fundamentals such as rental growth, operating efficiencies and tenant satisfaction have become increasingly important,” the statement read.

He also touted Cushman’s “full-service platform” and noted that he plans to take advantage of the firm’s “leasing, property management, development services and valuation and appraisal services.”

Eastdil has long had an advantage because of its ties to Wells Fargo, which provides financing to a number of its clients. But JMP’s Germain said that Harmon and Spies will be able to leverage Cushman’s property management and leasing services in a way they could not at Wells. “I’m not sure how much Eastdil is able to leverage the Wells platform,” Germain said.

Sources said that while ongoing deals at Eastdil must stay with that firm, Harmon and Spies will undoubtedly try to resume working with their existing clients.

The ripple effect

Despite its weak showing in the numbers, Cushman has actually been a strong player in the mid-market investment sales space.

In 2015, it did 242 overall transactions compared to Eastdil’s 56 and CBRE’s 44. It’s just that the deals were not blockbusters.

So there’s a lot riding on the Harmon-Spies team to change that.

But rivals to both Cushman and Eastdil also smell opportunity.

For years, the highest profile tug-of-war at the top of the investment sales industry was been between Eastdil and CBRE. But in recent years, the gap in annual between the firms has widened — from under $2 billion in 2011 to $13.9 billion in 2015.

CBRE’s investment sales division, which is led by Darcy Stacom and William Shanahan, still delivers its share of whopper trophy deals. For example, it brokered SL Green Realty’s $2.3 billion purchase of 11 Madison Avenue last year — the largest single-building trade in the city’s history.

But now CBRE — which has faced its own corporate struggles and internal political issues — may have a new chance to close the gap, sources say.

There may also be room for JLL and HFF to grow their market shares on the Class A trophy circuit.

In addition to that primary competition, other brokerages view the shake-up as a chance to gain ground in investment sales.

Simon Ziff, president of Ackman-Ziff Real Estate, which is ramping up its investment sales practice, is one of them. “We have been predicting major movement as a result of a variety of market conditions and expect to take advantage of them,” he said.

And if Cushman does shift its focus toward the big deals, the mid-size firms are hopeful they can take a bigger bite out of the middle market and outer boroughs, where Cushman became dominant after buying Massey Knakal.

“This could be a blessing in disguise for the smaller brokerages,” said an executive at an investment sales brokerage. “Expect to see a shakedown.”