For both Hollywood and NYC real estate, January marks the self-congratulatory awards season, when the most talented and highest-paid stars come together to put on a feel-good, well-oiled show. But disruptions can happen.

At last year’s Academy Awards, the dearth of minority nominees spawned the #OscarsSoWhite protest, capped off by host Chris Rock delivering a scathing and controversial opening monologue that skewered the establishment.

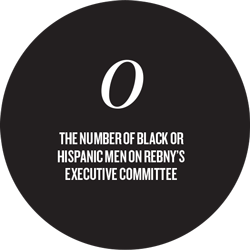

Not unlike Hollywood, real estate in New York has long been viewed as an insular world where, on balance, white men pull the strings. While compared to past decades, the galas hosted by the Real Estate Board of New York have featured a broader cast of characters — including the organization’s first black president, John Banks III, who was appointed in 2014 — the picture of the industry is hardly a mosaic. This year the powerful lobbying group will honor seven individuals, all of them white and only two of them women.

And barring a major MC shakeup, it’s safe to say that New York real estate is not about to have a Chris Rock moment.

“The culture is closed,” said Gabriel Silverstein, who heads the New York-based capital markets brokerage Angelic Real Estate. “It’s not good about change, and it’s not good about outsiders.”

The numbers bear that out. A 2014 survey by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission showed that whites hold 74 percent of the city’s professional real estate roles, which include sales positions as well as senior and midlevel office management jobs. Women, meanwhile, hold only a 35 percent share of those jobs on the whole. The imbalance becomes more pronounced further up the ladder: At the senior level, only about 22 percent of NYC’s real estate industry are women, and nearly 86 percent are white.

As Jesse Keenan, a faculty member of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, pointed out, what this essentially means is that the people involved in building NYC’s skyline bear little resemblance to its 8.5 million inhabitants.

Don Peebles

So why exactly has NYC real estate been so slow to adapt to the city’s changing demographics, and how do developers, executives and brokers, especially women and minorities, feel about it? To find out, The Real Deal talked to more than 70 players of all ranks — men as well as women, whites as well as minorities — from a cross-section of the industry, including residential sales, development, commercial leasing, investment sales and law.

Unsurprisingly, we found a tale of two sectors. Residential real estate, unlike commercial, has a roughly even number of male and female brokers. And that balance extends to the C-suite, where there are currently women CEOs — Dottie Herman, Pam Liebman and Diane Ramirez — helming the city’s three biggest brokerages, Douglas Elliman, the Corcoran Group and Halstead Property, respectively.

But a very different reality exists on the commercial side, where the numbers are much more tipped against women and minorities. Many industry players described that sector as a high-risk, “rough-and-tumble” world, where entrenched discriminatory practices surrounding access to credit, commission-based pay and a clubby, male-dominated culture have raised the barrier to entry.

For those who have broken in, the industry can seem tone-deaf at best and impenetrable at worst. CBRE’s Mary Ann Tighe, one of Manhattan’s top commercial brokers, recalled in a recent speech that after she was appointed REBNY’s first female chairman in 2010, one of the first questions she was asked was whether she would change the menu at the trade group’s annual banquet — a job she made very clear was not hers.

Don Peebles, the city’s highest-profile black developer, who had been one of three black members on REBNY’s roughly 150-member board of governors, recently quit before the end of his two-year term. “The agenda that was discussed was never a progressive agenda,” he said, referring to diversity issues. “I thought REBNY in general had lost sight of what city you’re doing business in.”

(Asked for comment, a REBNY spokesman said, “Mr. Peebles was a member in good standing, and we’d welcome him back any time.”)

In contrast, outside of real estate, race and gender issues have bubbled to the surface across a range of powerful and moneyed sectors.

In response to growing criticism and a push from government regulators, Wall Street and Silicon Valley firms have in recent years released their employee demographic data and instituted targeted recruiting efforts. More and more, women and minorities within industries are speaking out. Last summer’s sexual-harassment scandal at Fox News laid bare a culture of sexism at one of the most successful and impenetrable news empires. In the NFL, meanwhile, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s national-anthem protest brought the Black Lives Matter movement into the sports arena.

And of course, Hillary Clinton’s failed presidential campaign against Donald Trump, one of the industry’s own — who called Mexicans “rapists” and once boasted that he could grab women “by the pussy”— has prompted discussions about race and misogyny within politics and beyond.

But in many ways, NYC real estate has always operated by its own rules, and according to those interviewed, diversity is still an uncomfortable topic. Many firms, including Cushman & Wakefield, among the top three largest commercial brokerages in the world, declined to participate or have any of their brokers interviewed in this story.

To be sure, the industry has become increasingly international, especially as the flow of foreign money grows. Today, many of New York’s biggest real estate players hail from countries such as Iran, Syria, Israel and China.

To be sure, the industry has become increasingly international, especially as the flow of foreign money grows. Today, many of New York’s biggest real estate players hail from countries such as Iran, Syria, Israel and China.

And not everyone viewed real estate’s gender and racial imbalance as a problem. A number of women said they had never found their gender to be an impediment in their careers.

“There has never been a ceiling,” said Daun Paris, who co-founded Eastern Consolidated in 1981 with her husband, Peter Hauspurg. “Whether you’re a man or a woman, it’s about being at the top of your game and offering a service.”

Similarly, Jennifer Bernell, director of development at Kushner Companies, said, “I think it’s all about proving yourself, no matter who you are.”

Still, others argued that issues of gender and racial equality are often either misunderstood or ignored in the industry, addressed piecemeal rather than treated as a broader problem.

Thorobird Companies’ Thomas Campbell, a black, Manhattan-based affordable-housing developer, said the issue isn’t whether individuals have personally experienced discrimination but whether groups or classes of people have. “You have to differentiate between holding one person back and holding a group of people back,” he said.

Kendrick Harris, a black real estate attorney at the law firm Goldstein Hall who heads the Council of Urban Real Estate, said diversity has become “an ugly code word in the place of affirmative action.”

“The simple answer throughout the industry, especially from those with the most influence, is that this is a business, and we don’t get into social issues,” he said. “But that’s a little bit of a cop-out, because our social issues frame our professional interactions.”

He added, “You can’t operate in a vacuum.”

Check your privilege

In 2013, Peebles and his partner, the Israeli-based American real estate company El Ad Group, purchased a 13-story building at 108 Leonard Street from the city for $160 million.

At the time, the Tribeca property was described as the single largest building ever sold by the city, and Peebles called it a “barrier breaker.”

Knowledgeable sources told TRD last month, however, that it was also significant for another reason: It was priciest deal ever made between the city and a minority developer.

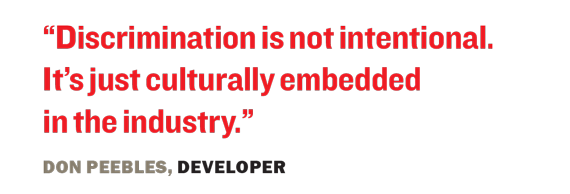

“That’s not a testament to my company’s abilities as much as it is an indictment of the unfairness of the system,” said Peebles, who is contemplating a run for mayor. “Discrimination is not intentional. It’s just culturally embedded in the industry.”

Peebles — who first entered the NYC market in 2008 after accumulating a $4 billion portfolio in Washington, D.C., and Miami — and El Ad are now finally moving forward on the Tribeca site. Last February, they secured $411 million in financing for a 144-unit luxury condo conversion.

Chris Okada of Okada & Company and Angela Howard of Jonathan Rose Companies

But Peebles is not the only one who’s run up against NYC real estate’s high barriers to entry. The cost of land is high, information is tightly held, and despite a surge of public REITs over the last few decades, the industry is still dominated by private and family-run companies that largely cling to one mold.

Of the top 20 wealthiest NYC real estate moguls in a 2013 Wealth-X report, all were white and 18 were Jewish, according to a tally compiled by the website Jewish Insider. (Only one individual in the ranking was a woman — Katherine Farley, developer Jerry Speyer’s wife, who worked at Tishman Speyer until February 2016.)

Within the group of owners and managers on REBNY’s board of governors, there are only two minorities — Bernard Warren of Harlem-based developer and brokerage Webb and Brooker, and Manhattan-based developer Young Woo — and nine women out of 107 members, according to a TRD review of website photos.

The pattern has also held true on the commercial brokerage side. Among 2016’s 10 largest Manhattan office lease deals, none involved a nonwhite broker. Four of the deals, however, involved at least one female broker, according to a review of CoStar data.

In a tight-knit industry that hinges on moneyed relationships, white privilege becomes more critical, experts say.

“The whole question is about access to capital, access to those networks,” said Lyneir Richardson, executive director of the Center for Urban Entrepreneurship and Economic Development at Rutgers University.

Within this environment, past deals or “experience” is often used as the litmus test, both for raising capital and winning deals. That may be true everywhere, but experience can often pose a cruel catch-22 for women and minorities in real estate: They don’t have enough of it because these jobs were historically reserved for white men. Add to that a slow turnover at the upper echelons, and what you have is a very steep climb.

Steve Bodden, who is originally from Honduras, founded his own Manhattan-based boutique commercial brokerage firm, Sanchez Bodden Lerner, in 2005. He said minority-owned firms have a particularly difficult time breaking into real estate because they are often stigmatized and viewed as less experienced.

“They are overlooked. Clients think they’re getting an inferior service or product, and that’s not the case,” he said.

Karim Hutson, a black affordable-housing developer who works on projects in Harlem, said that for minorities, experience can also be used to mean “where you come from and who you know.”

“[It] becomes a big word…to really [suggest] a lot of different meanings,” he said. “If you’ve been in the marketplace and got a firm you took over from your dad, who took it over from your granddad, it’s going to influence your access to capital [because of] people’s interpretations of who you are.”

“[It] becomes a big word…to really [suggest] a lot of different meanings,” he said. “If you’ve been in the marketplace and got a firm you took over from your dad, who took it over from your granddad, it’s going to influence your access to capital [because of] people’s interpretations of who you are.”

Minorities who do succeed often come from groups that have wealth or are fueling a boom.

Chris Okada, a second-generation Japanese-American commercial real estate executive, said that back in the 1970s, when his father was starting out as a retail broker, a big key to his success was his ability to connect with huge clients like Toyota and Panasonic to place them in premier buildings like 9 West 57th Street and the Seagram Building.

“In the pre-internet era in New York City commercial real estate, that was 1,000 percent the reason why our family was very successful,” said Okada, who now runs his own commercial brokerage, Okada & Company.

But he said the advantage has faded amid the rise of multinational companies.

Today, he said, there’s a huge network of Asian investors, property holders and banks like Bank of China and East West Bank. “You have these massive, trillion-dollar institutions pumping capital into real estate in Manhattan, and that trickles down to mortgage brokers, title people, you name it. I don’t know if there’s necessarily that infrastructure” for other groups, he said.

In fact, black and Hispanic players seeking to raise capital through traditional sources like banks face a legacy of institutional racism that has effectively made it harder for them to own property, let alone break into development. Although “redlining,” or denying mortgages to minority borrowers, was outlawed by the Fair Housing Act in 1968, the policy has persisted in the form of tighter lending standards for minority borrowers, as well as banks that avoid black or Hispanic neighborhoods.

Beyond home mortgages, a 2010 federal study showed that minority-owned firms with annual gross revenue under $500,000 are denied loans about three times as often as their white counterparts. For firms with annual revenues of $500,000 or higher, the loan rejection rate was almost twice as high. And those who did secure loans faced higher interest rates — on average, 7.8 percent compared to 6.4 percent.

Peebles said that as a black developer, he’s had “to answer a whole lot more questions” to raise equity. He recalled one instance in which a lender grilled him over a $500,000 lawsuit a broker had filed against him 15 years earlier. “It was a run-of-the-mill lawsuit. Five hundred thousand dollars is insignificant, meaningless to me and my balance sheet. I know my peers do not get those types of questions,” he said.

Dawanna Williams — who founded the Manhattan-based Dabar Development Partners in 2003 after working as a commercial real estate lawyer — said banks tend to be “less generous” with women- and-minority-led development firms.

Williams, who is black, said that could be because those companies tend to be smaller and therefore riskier to lend to. Still, she said, bias is partially at play.

“I think that the banks are making decisions on objective criteria, mostly,” she said. “But there’s some areas where there’s some subjectivity. I think there needs to be more discussion around inclusion. Many of the bankers have grown indifferent to inclusion if they are not forced to do something legally.”

Those realities prompt more minority-led development companies to move into affordable housing, where there are government subsidizes available to build, she said.

But the issues tied to race and gender in the industry go beyond raising money.

On the commercial brokerage side, women and minorities are often weeded out at the front door, according to many.

More than any other practice, sources singled out the commission-based structure in brokerage as an explanation for why the commercial industry fails to develop a pipeline of talented minorities and women. The cold terms of employment harken back to the age of trade apprenticeships: Brokers are typically paid nothing or “staked” an annual salary that they must pay back once they start making deals.

“It’s burn and churn,” said one woman at a prominent New York brokerage who asked not to be named.

Thrown into a bullpen, freshman office leasing and investment sales brokers have about a year to learn the ropes, honing their pitches by cold-calling as many as 50 to 70 people a day. Some have likened the first few years to a kind of hazing, where brokers must submit to menial tasks demanded by their superiors. “It’s like frat life. They get beaten up,” said Camille Renshaw, head of commercial sales at Ten-X, an online commercial brokerage.

And unlike residential brokerage, where a rookie can start by notching a few rentals on his or her belt, putting together a commercial deal takes time — and luck. Many don’t make it. Especially for blacks and Hispanics, who have historically ranked behind whites on the socioeconomic ladder, the jobs are high-risk for those without a financial safety net.

That’s why some in the industry, including REBNY’s Banks, have argued that real estate loses the brightest minority candidates to other industries, like finance.

Even among those who enter the field, the income volatility — along with the long hours — can make retention difficult, especially for women who have children and particularly in the notoriously scrappy tenant leasing world, the easiest point of entry in commercial brokerage.

In short, brokerage industrywide can be feast or famine. And it requires a certain type of personality, many people said.

Faith Hope Consolo, the chairman of Elliman’s retail leasing and sales division, said that while she was in a financial position to attempt a career in brokerage, not everyone is.

“You not only need nerves of steel, you have to live on the edge,” she said.

Wonder women

In October, the Commercial Real Estate Women’s (CREW) Network held a three-day conference at the New York Hilton. The event, which draws nearly 1,500 people from all over the world, is the largest of its kind for women in commercial real estate.

On one of the mornings, a psychologist named Amy Cuddy stood before the female audience, teaching them to perform a Wonder Woman-like “power pose” to build confidence. Throughout the lunch, the women jokingly mimicked the Amazonian hero, defiantly standing with their legs apart and their hands on their hips.

But the highlight of the day was a speech by Tighe.

At 68, Tighe is in a rarified group in commercial brokerage that includes Tara Stacom, who works at Cushman & Wakefield, and her sister Darcy Stacom, who heads up investment sales at CBRE. In 2002, after 18 years of rising in the ranks at Edward S. Gordon Company — later Insignia/ESG Inc. — Tighe was appointed the head of CBRE’s tri-state operations.

Standing in front of a crimson-lit background, Tighe took off her glasses and played to the crowd.

Standing in front of a crimson-lit background, Tighe took off her glasses and played to the crowd.

“When I look out at this room filled with commercial real estate women professionals, women from all over North America, from every sector of our industry, I have this moment when I realize how very far we’ve come,” she said. “I know in my heart that the days of being the only woman at the negotiating table are over.”

The numbers, however, paint a much grimmer picture.

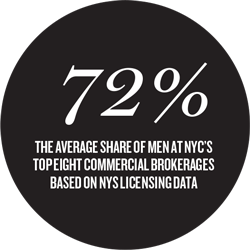

Among the city’s eight largest commercial brokerages (by number of employees), men on average make up at least 73 percent of brokers, according to a TRD gender analysis of names on state licensing data.

Cushman & Wakefield, which has more brokers than any other commercial firm in the city with 486, also has the highest share of men at 73 percent, while CBRE, with 462 brokers, is at least 70 percent male.

Likewise, a review of the websites of the city’s top commercial brokerages shows a consistent scarcity of women at the top, reflecting the much-talked-about C-suite gap that plagues corporate America.

Cushman, which is in the thick of a reorganization of its top brass, has no women in upper management. Newmark Grubb Knight Frank has four, while CBRE — a public company — has four female senior corporate executives, roughly 17 percent of the firm’s C-suite. JLL, which is also public, has two women on its global executive board. None of the firms would confirm their diversity numbers.

The gap translates into pay. CREW, for example, found that women in real estate make 23 percent less than men across North America.

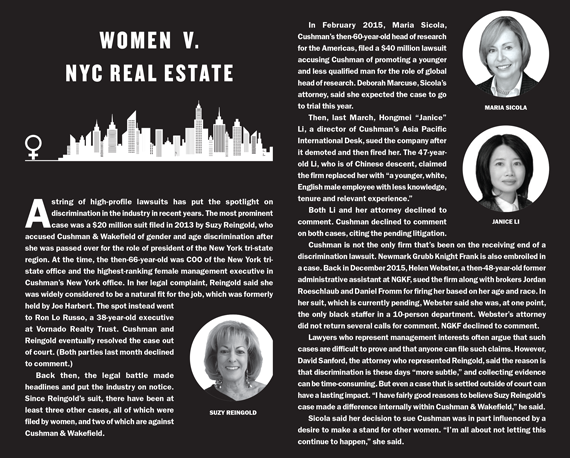

Suzy Reingold, the former COO of Cushman’s New York tri-state office, noted that breaking into the C-suite is even more difficult than becoming a star broker.

“You’re not judged on new clients. Whether you get ahead or not is judged by men. Because above you are all men,” said Reingold, who sued Cushman for gender and age discrimination in 2013 after getting passed over for a promotion.

For women, it means that critical companywide policies that arguably impact them disproportionately — such as compensation structure, recruitment, work culture and family-friendly benefits — are largely left in the hands of men.

“It’s hard to have children and not lose your place on the ladder,” Belinda Schwartz, who heads up the real estate practice at law firm Herrick Feinstein, told TRD when asked about the most difficult hurdle women face.

Maryanne Gilmartin

Many women, even those who have “made it to the table,” spoke of an industry where sexism still prevails, where it is implicitly understood that “men will be men,” and where women must walk a fine line between being smart and not being overly aggressive.

Lisa Bevacqua, senior vice president and director of asset management at Silverstein Properties, said she’s noticed that she’s consistently ignored in meetings when others in the room don’t know her title. Men from other companies, she said, often only address each other, even when she specifically asks a question. She said the behavior, while unintentional, is revealing.

“That’s the default,” she said. “They default to assuming that the man would be the one they will be working with.”

Alison Novak, a principal at the development firm Hudson Companies, recounted a meeting where a man from another company repeatedly referred to another woman they were working with as “that girl.”

One female real estate attorney, who asked not to be named, said she lost out on a client who felt that she couldn’t be aggressive enough as a woman. He told her, “I need a prick,” she said.

There are currently at least three pending discrimination lawsuits filed by women against major real estate companies in New York [see sidebar on page 45].

In general, female developers are few and far between. High-level women executives at development companies include those who were born into family-run firms, such as Amy Rose, Helena Durst, Samantha Rudin, Veronica Mainetti and Michele Medaglia. A few others have ascended the ranks at big firms, such as Extell’s Raizy Haas, Forest City Ratner’s Susi Yu and Lend Lease’s Melissa Burch. And there’s a smaller subset of women who have launched their own development companies. Toby Moskovits and Abby Hamlin are among them.

MaryAnne Gilmartin, who was named president and CEO of Forest City Ratner in 2013 after 19 years at the company, is perhaps the industry’s most prominent female development executive.

All told, her company — like Extell, Silverstein and a handful of others — has a relatively high percentage of women.

“Women represent 60 percent of our development team,” Gilmartin said. “Unfortunately, I think, that’s not the typical statistic.”

She added: “It’s not enough for people to talk about diversity and meritocracy in the workplace or say that women are on an even playing field. It has to be true.”

Gilmartin recalled a meeting 10 years ago when she accompanied Bruce Ratner — then the firm’s CEO — to negotiate a lease renewal with the head of a finance company that was a tenant in a Forest City building. Gilmartin said the male executive treated her as if she were being interviewed for a job, peppering her with questions about her experience level.

“He attempted to rob me of my dignity right there in the room as a way to create the upper hand in the negotiations or just because that’s how he viewed women,” she said. “Bruce really drew the line. It wasn’t a great feeling knowing that I could have stood up for myself but I was intimidated by the environment, because there were three white men and myself in a room. I should have been able to say, “This is not acceptable,” stand up and walk out, but instead I relied on Bruce to do that for me.”

Many women TRD spoke to — at least ones who’ve made it to the top of the industry — said they accept real estate’s male-dominated culture as a fact of life.

“You can’t cry or be a whiner,” said Adelaide Polsinelli, an investment sales broker at Eastern Consolidated. “This is not for the faint of heart.”

Wendy Silverstein, the incoming CEO of New York REIT and a former top executive at Vornado Realty Trust, echoed that point.

As a woman in any male-dominated industry, you learn to expect to be treated differently at times, she said. “If you are a man and you are smart and tough, you are called a good negotiator. If the same is true of a woman, she is usually called a bitch.”

‘They did right by me’

In 1999, Helen Hwang landed a job at Cushman & Wakefield’s appraisal division. She was 24, recruited into the company’s career development program, which was designed for recent college grads.

In many ways, it was an unexpected fit. She grew up in a small village in the South Korean province of Kyungki-do, where her father had worked as a livestock broker. Her family moved to the U.S. when she was a teenager. In West New York, New Jersey, she learned the language and adjusted to her new culture. She wound up attending Cornell University, where she started as pre-med and switched to real estate finance.

In many ways, it was an unexpected fit. She grew up in a small village in the South Korean province of Kyungki-do, where her father had worked as a livestock broker. Her family moved to the U.S. when she was a teenager. In West New York, New Jersey, she learned the language and adjusted to her new culture. She wound up attending Cornell University, where she started as pre-med and switched to real estate finance.

During the training program at Cushman, she noticed that many of the other recruits had personal connections in the industry. “Almost everybody knew somebody,” she said. “I knew nobody.”

Still, after about two years in the appraisal division, she moved into one of real estate’s most competitive fields: investment sales. Once there she joined a roughly 25-person team anchored by seasoned veterans, Richard Baxter, Scott Latham, Ron Cohen and Jon Caplan. The group was diverse, with “many nationalities,” but had only three other women, she said.

In 2010, when Baxter and company jumped to JLL, Hwang assumed she’d go with them. But instead, Arthur Mirante, Bruce Mosler and Glenn Rufrano — three generations of Cushman CEOs — tapped the then-34-year-old to rebuild the firm’s investment sales team from scratch.

Despite its impenetrable circles, the tantalizing (albeit slightly clichéd) appeal of NYC real estate has always been its potential for a pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps war story.

Women have their place in that narrative as well.

Tighe tells a story about a lunch meeting she had with her then-boss at Insignia/ESG in 1997. After asking him what it would take to become vice chair of the company, he took out a pen and sketched the company’s male-only hierarchy. “This is why it’s never going to happen,” he told her.

Two years later, she was named vice chair.

Hwang, who left Cushman in 2015 to head the investment sales team at Meridian Capital, stands out because she is both Asian and female. Early in her career, she was more self-conscious. Slights, she said, such as people failing to acknowledge her or shake her hand, made her blame her gender, race and relative youth.

However, over the years, those fears subsided.

“I realized it’s not really about me. It’s more about issues, deals, and clients,” she said. In the end, she added, “I think we all speak the same language. We are all deal people.”

With regards to Cushman, she said, “They did right by me.”

Many women in development and commercial real estate said the presence of such trailblazers is a good sign. “I think it’s very important that there’s visibility,” said Burch, who leads Lend Lease’s new development platform. “You need these role models, women who are out there, showing you clear examples of being effective in the industry.”

Angela Howard, a director at Jonathan Rose Companies and one of the few black women in development, had a similar take, calling those trailblazing women in architecture and construction the “giants on whose shoulders we stand.”

She added: “It’s not there yet, but we’re moving in the right direction.”

Karim Hutson of Genesis Companies and Gabriel Silverstein of Angelic Real Estate

Yet while women have forged a path to prominent roles in the industry, the same has not been true for minority men.

“They don’t have trailblazers to follow, so they’re blazing their own trails,” said Ken McIntyre, a consultant who previously led MetLife’s commercial lending team. “You burn a lot of fuel when you’re blazing your own trail.”

Confronting reality

About four years ago, David Kramer needed to come up with a family leave policy for his growing development firm, Hudson Companies. He began by calling a few other companies. But the responses fell short.

“I got answers like, ‘Our baby was well-timed. We had it on a long weekend, so I was back in the office Tuesday,’” he said.

Kramer saw a chance to repair a longstanding inequity in families.

“I have three kids, and so, I’ve gotten to know the dynamics of parenting pretty well,” he said. “I think it’s pretty consistent that most mothers are pretty violently hostile towards dads overall because the truth is that parenting responsibilities aren’t 50/50.”

Under his company’s plan, all new parents, fathers included, receive three months of paid leave. The benefit rivals that of elite tech companies in going far beyond what most private companies provide. Under the Family Medical Leave Act, employers with 50-plus staffers are generally required to provide 12 weeks of unpaid leave for the birth of a child.

Other companies have taken action as well.

Several years ago, as part of its hiring and recruitment efforts, Jonathan Rose Companies introduced a selection committee that considers diversity in tandem with ability.

Its CEO founder, Jonathan Rose, who himself belongs to a real estate dynasty (he and Amy Rose are cousins), said he frequently receives calls from well-connected industry colleagues asking if he can hire one of their friends or relatives. He now responds by saying he’s not on the selection committee.

“That really helped us choose from the best rather than build a company on people we know,” he said.

Of the 73 employees at his firm, 52 percent are women and 32 percent are minorities.

Many pointed to these policies as signs that change is seeping, albeit slowly, into the industry.

In some cases, it’s a matter of passing the family torch.

Along with the increasing number of REITs, many of the long-standing real estate families, the Trumps included, have already tapped their daughters for upper-level management.

Meanwhile, REBNY’s choice of Banks as its president was widely seen as a big leap forward in the industry. In an interview with TRD last year, Bertha Lewis, president of a NYC-based think tank, the Black Institute, called the appointment “a supernova.”

Yet minorities in the industry have mixed views on how much of a personal obligation Banks has to lobby for more inclusiveness.

“You don’t want to put someone in the position of being the sole flag-bearer of the issue,” said Goldstein Hall’s Harris. “His job there is representing the owners, so it would have the effect of putting him in a very difficult position. It’s much easier for a white senior professional than it is for a senior-level black professional, quite frankly.”

Banks told TRD that he doesn’t see pushing diversity as his mandate. “I think that each individual company has to determine how best to do that. There’s a significant difference to how each of these organizations are run.”

He added: “You can’t just go and ignore the structure that has grown up over two or three generations and make it change.”

The real push, some say, will come from demographic shifts. “You don’t negotiate with reality,” Rose said. “Diversity is reality.”

According to the Pew Research Center, by 2055, whites will no longer hold the majority in the U.S. Women, meanwhile, are grabbing an increasing share of the educated workforce.

For its part, corporate America is making efforts to adapt to the new landscape. Last summer, General Motors quietly became the first major industrial corporation to achieve an even split of men and women on its board. And in August, Apple released statistics showing that 27 percent of its U.S. hires came from underrepresented minority groups — a 6 percentage point jump from two years ago.

Many in NYC real estate said that the most compelling reason to embrace diversity is something every business mind can relate to — the bottom line. Recent studies have linked better decision-making and business performance with both racial and gender diversity.

But more directly, the industry’s clients in corporate America have come to expect to work with a broader mix of real estate executives. “When you go to a meeting and you bring four white males to the table and the company has African-Americans, Asian women and two white guys, they look at you like you’re nuts,” Reingold said.

In the end, she said, it isn’t about altruism. “You do it because it’s good business.”

— Yoryi DeLaRosa contributed research.